Articles

Influence of the Hudson's Bay Company on Carrier and Coast Salish Dress, 1830-1850

Abstract

An examination of Hudson's Bay Company account ledgers from New Caledonia and Fort Langley from 1830 to 1850 reveals that during the fur trade, Carrier and Coast Salish had access to large quantities and varieties of European-manufactured dress goods. How these items were incorporated into their traditional clothing is shown through contemporaneous descriptions of their costume. While the types of clothing merchandise available to the Carrier and Coast Salish were similar, their use of them was different. The Carrier traditionally wore fitted, constructed garments made of tanned animal hides and fur. By 1850, they were wearing European apparel, probably because it was similar in fit and silhouette to their own clothing and required less effort to produce. Traditional Coast Salish costume consisted primarily of a blanket or robe wrapped around the body. Coast Salish had not changed to European dress style by 1850. Rather, they used European textile imports, such as woollen blankets, in their pre-contact style of dress. They may not have adopted European garments because these were too different from their own.

Résumé

Un examen des livres comptables des comptoirs de la Compagnie de la baie d'Hudson dans la région de New Caledonia et à Fort Langley, de 1830 à 1850, révèle que, dans le cadre de la traite des fourrures, les Porteurs et les Salish de la côte ont eu accès à des quantités et des variétés importantes de vêtements manufacturés en Europe. Les descriptions de leurs costumes rédigées à cette époque témoignent de la façon dont ces articles ont été intégrés à leurs tenues traditionnelles. Mais si les Porteurs et les Salish de la côte ont eu accès à peu près aux mêmes types de vêtements, ils en ont fait un usage différent. Les Porteurs avaient coutume de porter des vêtements artisanaux ajustés, faits de cuirs tannés et de fourrures. Dès 1850, on les voyait déjà en tenue européenne, probablement parce que celle-ci était aussi ajustée que leurs vêtements traditionnels et ne changeait rien à leurs silhouettes, tout en exigeant moins d'efforts de production. Le costume traditionnel des Salish de la côte se composait principalement d'une couverture ou d'une tunique drapée autour du corps. En 1850, les Salish de la côte n'avaient pas encore adopté la tenue européenne. Cependant, ils utilisaient des étoffes importées d'Europe, notamment des couvertures de laine, adaptées à leur mode vestimentaire d'avant les contacts. Il est probable qu'ils n 'avaient pas adopté les vêtements à l'Européenne parce que ceux-ci étaient trop différents de leurs propres tenues.

Introduction

1 Clothing and adornment can be viewed as a micro-environment that responds to physical and cultural needs.1 Dress theorists claim that clothing, as an outward symbol of a society's technology, morals, and aesthetics, reflects elements of cultural change.2 In North America, the fur trade, and its implications on the indigenous population, has been effectively researched by Innis,3 Ray and Freeman,4 Fisher,5 and Rich6 though the specific issue of the fur trade's impact on Native dress has not been queried. The fact that there are so many different indigenous peoples in Canada points to a variance in responses to the fur trade and to the European merchandise that came with it. One finds, however, that Natives are often grouped together when discussing them and the fur trade. Of British Columbia First Peoples, Duff stated:

Of the Athapaskans in general, Boudreau wrote:

There is little doubt that the fur trade affected Native clothing and adornment but little or no research has addressed the question of acculturation and dress (as Duff suggested but for which he did not provide quantitative evidence) or dress-style change resulting from the introduction of new merchandise or techniques. Nor, to my knowledge, has anyone carried out quantitative analysis of apparel and adornment available to Natives at trading posts in British Columbia.

2 Study of dress has been used to examine culture change and acculturation among Native groups in a few instances. Pannabecker9 researched the origins, diffusion, and persistence of ribbonwork among the Great Lakes peoples through examination of historic documents, ethnographic reports, artifacts, and oral histories. Grounds 10 documented the gradual shift of Navajo women from wearing a mantle frock to European-style fitted clothing through content analysis of dress features of extant costumes and garments shown in photographs. Historians of the Pacific fur trade have acknowledged that clothing and textiles were important trade items among northwest tribes11 yet none have actually researched dress-style change or the ramifications of change on apparel. Those researchers who have considered European influence on Native dress have concentrated on the obvious examples such as the production of button blankets and of tanned hide garments cut in European style.12 Blackman commented that although anthropologists at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were witness to "nearly a century of acculturative change, acculturation was not their primary concern and little evidence of it is acknowledged in their written work."13

3 During the fur trade period of British Columbia (ca 1770s-1850s),14 the Coast Salish of the Fraser River Valley and the Carrier of the northern interior had access to Hudson's Bay Company trading posts. These posts, Fort Langley (in the territory of the Kwantlen, a Coast Salish group) and Fort St. James (in Nak'azdli territory, a group of the Upper Carrier), have been restored as historic sites by the Canadian Parks Service. At these sites, both Eurocanadian and Native interpreters wear European "working class" clothing. Natives are represented by the inclusion of moccasins or capots. Questions come to mind with regards to the costumes worn at the two posts. Did all Natives with access to fur trade merchandise adopt European clothing irrespective of their aboriginal apparel? Late-nineteenth century photographs show people at Fort Langley and Fort St. James dressed in Eurocanadian clothing.15 Of the Carrier people, Father Morice, O.M.I. (1894) stated, "with the advent of the whites the dress of the western Dene gradually changed until it became, what is now, practically that of the Hudson's Bay Company's people."16 The broad questions of how, when, where, and why Natives adopted European dress cannot be answered in the narrow scope of this research. The question I wish to address is, What effect did European dress goods imported by the Hudson's Bay Company to Fort St. James and Fort Langley between 1830 and 1850 have on the traditional dress of the Carrier and Coast Salish? I chose the period 1830 to 1850 because during this time both these groups had continuous access to Hudson's Bay Company trade goods and were generally without the influencing factors of Christian missionaries, European government or school systems. Because little or no pre-contact or proto-contact clothing items have survived from the Kwantlen and Nak'azdli'ten, one has to rely on written evidence of clothing found in journals of early nineteenth-century writers. Hudson's Bay Company inventories provided data on the types and quantities of dress merchandise available at the posts and contemporaneous descriptions tell us how Natives used these products.

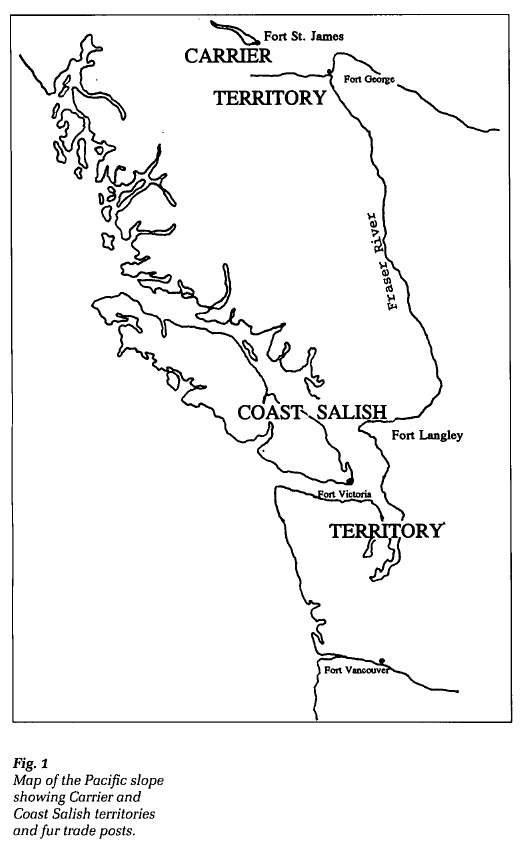

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 At the time of contact, the Carrier and Coast Salish wore clothing quite different from one another. The Carrier lived in the north, in a region that has warm, short summers and long, cold winters (Fig. 1). In aboriginal times, the Carrier dress consisted primarily of fitted garments made from tanned animal hides, such as caribou and deer, with or without the fur. Men wore tunics, leggings, moccasins, and in winter, robes, mittens, and hats. Women dressed much like the men though their tunic was generally longer.17 According to one Carrier elder, sturgeon and salmon skins were commonly used for footwear.18

5 The Coast Salish lived on the south coast where life-threatening weather is not a factor in their clothing; they wore draped garments. The most common garb was a woven blanket of mountain goat wool or dog hair, and vegetable fibres such as cedar and stinging nettle. Women wore tunics of woven material.19 The weaving tradition of the Coast Salish has been well documented.20 Barnett21 states that the Coast Salish also wore fur robes in cold weather along with leggings and moccasins.

6 Trade items imported by the Hudson's Bay Company were distributed to trading posts on the Pacific slope from Fort Vancouver. Fort Vancouver received its supplies directly from London; clothing and fabric comprised the bulk of these supplies. After 1848, Fort Victoria became the main supply depot.22 Ross states:

Method

7 Rich, and Ray and Freeman24 have researched consumer behaviour among Native people involved in the fur trade through examination of Hudson's Bay Company records. They found that during the fur trade the Hudson's Bay Company was attuned to what trappers wanted, so the Company rarely imported products that would not be traded. Often, the Company had to make adjustments over time to the needs and wishes of the Native trappers to ensure their continuing consumerism. There is evidence of some Native control over trade at Fort Langley:

With reactions such as this one, it was in the best interest of the Hudson's Bay Company to ensure that there were goods on hand that the Native trappers wanted. Fisher26 also noted the control of Natives over trade.

8 No study of consumer behaviour of British Columbia aboriginal people during the fur trade has been carried out in the systematic manner of Give Us Good Measure by Ray and Freeman. I thought that since these researchers were successful in determining the economic relationship between trappers and traders through an analysis of Hudson's Bay Company ledgers, these same ledgers could provide insight into the types and the extent of influence European-manufactured clothing had on Carrier and Coast Salish dress up to 1850, a situation that has not yet been queried.

9 In order to determine the types and quantities of textiles and garments imported to Fort St. James27 and Fort Langley, content analysis was carried out on inventories from 1830 to 185028 from the Hudson's Bay Company Archives (HBCA) in Winnipeg (available on microfilm).29 Inventories, which were taken on an annual basis, recorded all goods on hand; duplicate copies of New Caledonia and Fort Langley inventories were found in the Fort Vancouver records (HBCA B223 series).30 While the actual trade ledgers would have provided the most accurate information in determining goods purchased (these list the trappers with their individual credits and debits), the inventories at least tell us what was available for trade at Fort St. James and Fort Langley. Data obtained from the inventories were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSSx), a program effective in organizing and analyzing large amounts of data. All information related to dress was recorded on data sheets and entered into the program. Items were entered into categories such as clothing, yard goods, accessories, adornment, sewing notions, and grooming items. The name of the article and any descriptive information such as colour, size, and material were recorded. Quantities for each like item were noted as well as the unit of measurement. Once all data were gathered, goods imported to Fort St. James and Fort Langley could be compared using frequencies and cross-tabulations to determine if there were indeed markets for different products among the Carrier and Coast Salish.31

Findings

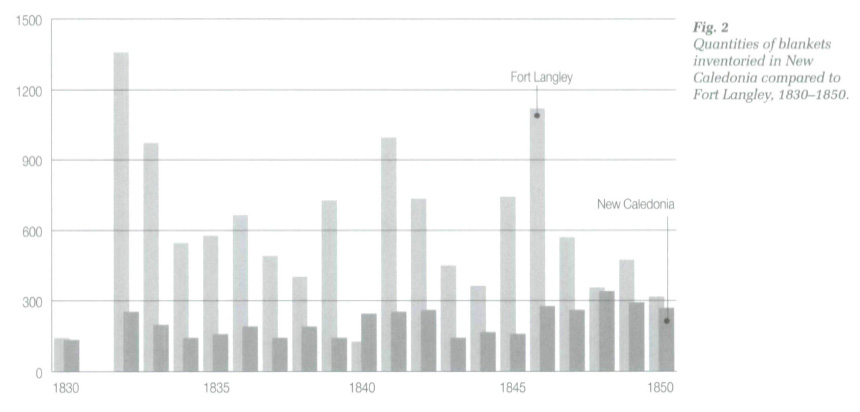

10 Analysis of dress goods and garments imported for trade at Fort St. James and Fort Langley yielded some interesting information. Results of the content analysis of inventories are summarized here; these include information on blankets, yard goods and notions, and garments. Woollen blankets were consistently inventoried in New Caledonia and Fort Langley from 1830 to 1850 (Fig. 2). From 1830 to 1845 the types of blankets listed were plain, green, and green-and-yellow striped. Plain blankets sometimes had red, blue, or black bands. Blue and scarlet blankets were introduced and recorded in the inventories after 1845. High numbers of plain blankets were listed in both regions though Fort Langley listed many more than New Caledonia. Up to 1844, plain blankets made up 85 per cent of blankets listed at both New Caledonia and Fort Langley. After 1845, plain blankets increased to 90 per cent of all blankets listed in New Caledonia, while at Fort Langley the numbers decreased to 72 per cent. At Fort Langley, an increasing percentage of blankets were made up of the newly introduced scarlet blankets; they quickly accounted for 13 per cent of blankets. A notation in the 1847 requisition for goods from Fort Vancouver referred to the importance of scarlet blankets:

This statement suggests that the colour scarlet made these blankets valuable; they may even have cost more than other blankets though I have not found any claim to this effect. Scarlet blankets made up only 5 per cent of blankets listed in New Caledonia during the same period.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 311 Blankets ranged in size from one point to four points, the former being the smallest. At Fort St. James, one size of blanket did not dominate; 41 per cent of blankets were three-point size and 27 per cent were two-and-one-half-point size. At Fort Langley, most blankets (83%) were of the two-and-one-half-point size, which would be suitable for wrapping around the body.33 Berthold Seeman observed the Coast Salish using blankets in this capacity: "their dress consisted of a blanket thrown loosely round the body — so loosely indeed, that on many occasions it certainly did not answer the purpose intended."34 He also noted, "since the Hudson's Bay Company have established themselves in this neighbourhood, English blankets have been so much in request that the dog's hair manufacture has been rather at a discount, eight or ten [English] blankets being given for one sea-otter skin."35 Marr has suggested that the fur trade may have provided a stimulus to Coast Salish weaving in the form of "nobility blankets," the brightly coloured and elaborately designed blankets produced in the mid-nineteenth century:

Not all these colours were available at Fort Langley or Fort St. James.

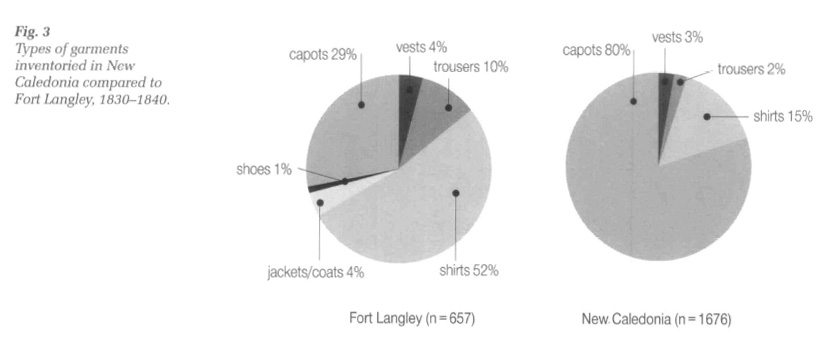

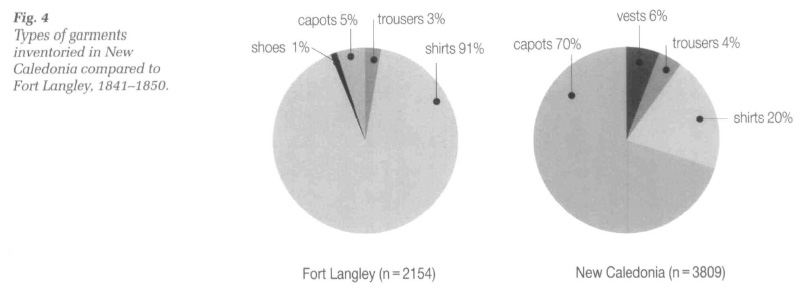

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 412 Clothing such as trousers, shirts, and capots were listed each year in New Caledonia and Fort Langley ledgers. Quantities of these items appeared to change in New Caledonia and Fort Langley from 1830 to 1850, so this time was divided into two periods. From 1830 to 1840 there was a difference between the two posts in the quantities of garments listed (Fig. 3). In New Caledonia, 80 per cent of clothing articles were capots; at Fort Langley, capots accounted for only 29 per cent. During the second period, 1841 to 1850, capots remained numerous in New Caledonia inventories (70%) but were reduced to 5 per cent at Fort Langley (Fig. 4). Capots were heavy, long, woollen overcoats, usually belted at the waist, in fabrics described as "common cloth," "Indian cloth," "blanketing," and "second cloth." Common cloth capots were most abundant. They came as plain, caped, or hooded. As Fort St. James is located in a cold climate, it is understandable that capots would be a useful garment. According to Harmon, capots were in demand from the very early period of the fur trade. He lived at Fort St. James from 1811 to 1818 and wrote of the Carrier:

13 Shirts were also inventoried in large quantities. From 1830 to 1840, shirts accounted for 15 per cent of garments listed in New Caledonia ledgers. This decreased during the second period to 10 per cent. In contrast, at Fort Langley shirts accounted for a high percentage of garments in both periods; 51 per cent during the first period rising to 91 per cent from 1841 to 1850. Such large numbers of shirts at Fort Langley suggest that the Coast Salish had begun wearing them on a regular basis.38

14 The types of shirts inventoried at New Caledonia were common striped cotton (37%), fine striped cotton (40%), and white flannel (23%). At Fort Langley, most shirts were made of common striped cotton (67%), common cotton (24%), and fine striped cotton (4%). Fort Langley inventories also included a few yacht or rowing shirts, red serge shirts, and fine printed shirts.

15 Other garments recorded at Fort St. James and Fort Langley included trousers, vests, shawls, and accessories such as garters, hose, caps, hats, and belts. Trousers were made of common cloth, drab corduroy, or olive corduroy and were not found in very large numbers at either post. The greatest number of trousers listed in New Caledonia inventories was 25 (in 1848) and 23 in Fort Langley (in 1833). Vests appeared in small numbers in both regions. New Caledonia listed vests in consistent numbers varying from 1 to 13 (1830 to 1840) and from 10 to 37 (1841 to 1850). Vests figured in the Fort Langley inventories in the years 1832 to 1836, 1844, and 1845. Small numbers of trousers and vests suggest they were not popular among the Carrier and Coast Salish. It may be, however, that these garments simply lasted much longer than other clothing. They may also have been reserved for gift giving during the early fur trade period; the Hudson's Bay Company initially provided trappers with gifts to entice them to come trade at their posts.39

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 616 Quantities of hose, garters, belts, and hats were high at both posts though Fort St. James counted as much as three times as many of these items compared to Fort Langley (Fig. 5). At both posts, garters were by far the most numerous product. Natives may have used them in a variety of ways other than holding up hose, such as with leggings, as straps for holding on capes, and sewn onto doming for decoration. No evidence of their use was located.

17 A large quantity of fabric, sold by the yard, was inventoried at New Caledonia and Fort Langley. While both cotton and wool fabrics were present, woollen yard goods were most abundant at both posts. From 1830 to 1840, the most plentiful fabric in Fort St. James ledgers was common stroud (58%). The remaining fabric included Hudson's Bay (HB) stroud (36%), baize (5%) and small amounts of second cloth and common cloth (Fig. 6). At Fort Langley, baize was the cloth of choice, accounting for 57 per cent of woollens inventoried along with 37 per cent common stroud. There was also a small amount of HB stroud listed. As stroud is a heavier weight wool than baize, it is logical that Fort St. James would import stroud over baize. Baize is well suited to the Coast Salish of me Fraser River Valley because of the damp, cool climate, but those at Fort St. James would require more substantial fabric to guard against winter cold.

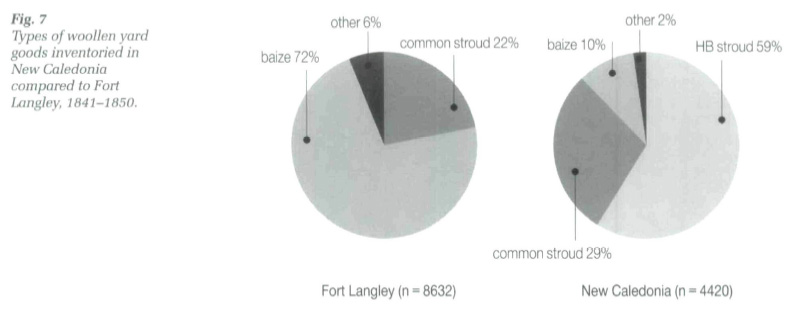

18 After 1841, HB stroud accounted for 59 per cent of woollens in New Caledonia records, common stroud 29 per cent, and baize 10 per cent (Fig. 7). Baize continued to be a standard at Fort Langley increasing to 72 per cent of total cloth between 1841 and 1850. Common stroud made up 22 per cent of woollen fabric with the remaining 6 per cent being flannel and common cloth. Woollens came in a variety of colours. Stroud was listed in four colours: scarlet or red, blue, green, and white. Baize was either red or green. Second cloth was sometimes listed as scarlet.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 719 Cotton fabric did not appear in large quantity at either New Caledonia or Fort Langley. Both posts listed small amounts of "common cotton" and very small amounts of "fine cotton." As the Company was importing so many cotton shirts, Natives may not have felt a need to make them. Osnaburg, a heavy cotton or linen fabric, was found in small but consistent quantities at Fort Langley. Light osnaburg was used for work clothes but "stout" osnaburg, as described in the inventories, was used for industrial purposes.40 This cloth may have been used for sails or tents.

20 To determine if imported cloth was being made into garments, the quantities of needles and spools of thread in inventory were analyzed. They both appeared in high quantities in New Caledonia. The consistency of large numbers of needles and spools of thread suggests that the Carrier were sewing a great deal. This would be in keeping with their tradition of making fitted garments. There are also several pairs of scissors listed in the New Caledonia inventories though no such listings appear in the Fort Langley records. Needles were listed in high numbers at Fort Langley but this did not correspond to an equally large quantity of thread. Most needles were darning needles; the large size of darning needles may have been better suited to the kind of sewing carried out by Coast Salish, such as affixing decorations to garments (not beads) or sewing wool fabric. Archaeological excavations have revealed that their pre-contact needles were made of bone and were quite large so darning needles would have been comfortable for them to use.41 Other sewing notions such as thimbles and buttons are found in large numbers at both posts. Fort Langley has as much as three times these items as Fort St. James. High numbers of thimbles (i.e., 2280 in 1840, and 2880 in 1841) listed at Fort Langley suggest that the Natives there may have been using them for tinklers. Buttons, almost all brass, are also found in much greater quantities at Fort Langley than New Caledonia. Tinklers made of thimbles or buttons would have been used on dance leggings, aprons, or capes.

Discussion

21 The Carrier and Coast Salish appeared to respond favourably to the presence of European garments and dress goods available for trade at Fort St. James and Fort Langley. Both groups would have had to trade many furs, salmon, and much labour to obtain this merchandise and they did so year after year. Clothing, textiles, and notions comprised the majority of goods for sale. Merchandise available to each group was similar but the quantities in which they appeared in the inventories were different.

22 The Carrier appeared more consistent in their purchasing as quantities and types of goods inventoried in New Caledonia remained fairly constant from 1830 to 1850. Items enumerated in large quantities included blankets, capots, shirts, woollen fabric, belts, and garters. Sewing notions such as thread, thimbles, needles, and buttons were also abundantly available. Woollen garments and fabric imported by the Hudson's Bay Company were well suited to the climate of Carrier territory. If the Carrier replaced their traditional clothing with European garments and cloth, they would require these supplies from year to year. This would account for a consistency in quantities of some dress goods observed each year in the New Caledonia inventories.

23 An incident described by Peter Skeene Ogden during his stay in New Caledonia in the 1830s tells us of some Carrier who dressed in European garb to impress him:

Judging by this statement, it appears that the Carrier had not yet fully adopted European or Eurocanadian dress though they did possess some items.

24 At Fort Langley, there was a greater occurrence of items appearing in large numbers for a few years and then disappearing. This suggests a more inconsistent market. Some products, such as beads, feathers, and bells, were introduced at Fort Langley and were purchased in large quantities for short periods of time. Then the Company apparently ceased to import these items or greatly reduced the numbers imported. This situation is similar to that which Hammell observed in his discussion of coastal Indians' response to European trade goods. He suggested that coastal tribes traded for new merchandise in large quantities until the market was saturated or the novelty wore off.43

25 Three items that appeared important to the Coast Salish trading at Fort Langley were blankets, woollen yard goods, and shirts. Blankets were listed in great quantities, which suggests that the Coast Salish were replacing their traditional blankets with English ones. Mayne observed the Coast Salish in the mid-nineteenth century:

They may have been using woollen fabric for wraps as well.

26 There are several reasons for the difference in adoption of European dress by the Carrier and the Coast Salish. When discussing acculturation and its effect on dress, Kaiser suggests that variables that affect the process of acculturation are aesthetics, observability, relative advantage, comparability, and complexity.45 When two cultures meet, the first exchange is commonly technology with morals usually the last thing to change among the groups involved. Descriptions of Carrier dress in the early nineteenth century suggest that they readily adopted European dress. The adoption of European dress by the Carrier is tied to its technical advantage, comparability, complexity, and aesthetics.

27 The technical advantage of European dress for the Carrier is that it was easier to obtain or to make than their pre-contact style of dress. The Carrier traditionally pieced together garments made of animal hides. Clothing production included trapping and skinning animals, tanning the hides, then sewing together pieces of hide with an awl and sinew. European fabric or garments could be obtained at the fur trade post for raw furs, thus eliminating much labour. Fabric is easier to cut and sew than hide. Needles, thread, and scissors facilitated sewing and garment construction. Also wool, the main fabric imported to Fort St. James, is well suited to the climate of Carrier territory. Traditional Carrier dress was fitted to the body, similar to European garments. Thus a change in material did not necessarily translate into changes in dress style. The Carrier did not abandon their pre-contact garb once they had access to European dress, however; Father Morice witnessed the production of ceremonial wear made in the pre-contact style used by the Carrier as late as the 1890s46 though, as mentioned earlier, he described the Carrier as having adopted European dress. The Hudson's Bay Company imported moose hides for trade with the Carrier, demonstrating that the Carrier still needed hides for making items such as moccasins and leather tunics. The complexity of European dress would not have been a hindrance to the Carrier. European men's clothing had been simplified by the early nineteenth century and Carrier women did not appear to adopt the complicated style of European women's apparel.47

28 Finally, Carrier aesthetics influenced their acceptance of European dress. The soft drape and bright colours of European woollens and blankets contrasted sharply with the natural colours of animal furs. The bright colours probably appealed to the Carrier because of their novelty. Some Nak'azdli elders recount that plaid shawls and paisley head scarves were especially popular; one woman from Nak'azdli was renowned for the number of colourful petticoats she used to wear.48

29 Contrary to the Carrier, access to European textiles appeared to stimulate the Coast Salish production of their traditional dress. Coast Salish garb consisted primarily of a blanket wrapped around the body, pinned at the shoulder and often tied at the waist.49 Blankets were woven of cedar bark fibres, mountain goat wool, and dog hair. From its earliest introduction, it appears that west coast people used cloth to replace their own woven cloth. A member of Captain Vancouver's crew observed:

Of the products available to them through the fur traders, the Coast Salish tended to use clothing items most similar to their aboriginal dress and materials similar to their pre-contact form (i.e., woollen fabric and blankets).

30 There are several reasons why the Coast Salish limited their adoption of European garments and dress goods. The most evident is the importance of the blanket in Coast Salish culture. Blankets were the main costume and blanket production was closely tied to their social system. Blankets were important potlatch gifts and became even more so with access to Hudson's Bay blankets.51 Now quantity, rather than quality, was the feature of the potlatch giveaway. Even the term "blanket throw" or "blanket scrambles" implies a casual distribution of blankets, probably due to the numbers involved.52

31 Aesthetics were also important. The Coast Salish ideal of fashionability or appropriate forms of attire was quite different from Euro-Canadian styles of dress. Coast Salish apparel was too removed from its European counterpart in fit and silhouette to allow for a quick transition from one style to another. Dress theorists claim that moral and social pressures affect change in clothing53; because Coast Salish dress was tied to their social structure, change in dress would probably not occur until there were changes in their culture. Overall changes in lifestyle brought about by the fur trade were probably minimal; more profound change occurred with the conversion to Christianity and with external government control over Natives.54

32 A third factor affecting the Coast Salish adoption of European dress was technology. Traditional Coast Salish dress is draped rather than cut and constructed. The Hudson's Bay Company provided fabric, thread, needles, and garments that could be used in clothing production (garments for prototypes). Knowledge for making fitted garments would have to be acquired. This acquisition of knowledge would be slowed if the culture had little desire to produce these garments. This may have been the situation among the Coast Salish as judging by the amount of thread and needles imported to Fort St. James and Fort Langley; it is evident that the Carrier were sewing much more than the Coast Salish.

Conclusion

33 This research demonstrates that two Native cultures in British Columbia responded differently to the presence of European merchandise and that European dress goods were incorporated differently into Native traditional dress. The fur trade had an effect on Carrier and Coast Salish costume; however, the influence was not necessarily to produce Natives who dressed like Europeans. Rather, Natives made use of European dress goods for clothing production much like their pre-contact dress style. In the case of the Carrier, their clothing became similar to that of the European traders because it was not so different to begin with. The Coast Salish did not adopt European dress style; instead they replaced their traditional woven blankets and robes for European fabric and blankets. The large quantities of blankets and wool fabric inventoried at Fort Langley point to this fact; the contemporary descriptions of Coast Salish dress confirm this conclusion.

34 Fort St. James and Fort Langley received merchandise from Fort Vancouver, which means they could have received identical types of trade goods. Inventories reveal that they did not; this suggests that Native demands were dictating the type of merchandise imported.55 The inventories included different quantities and often different types of merchandise (i.e., different weights of wool fabric). Carrier and Coast Salish dress was different before the arrival of fur traders and this difference continued into the fur trade period. Despite the unifying factor of having access to European dress goods, the two groups chose to adopt and use different goods. This allowed them to continue developing their own style of dress at least until 1850.

35 This research has provided quantitative data to queries on the influence of the Hudson's Bay Company fabric and dress goods imported for trade with the Carrier and Coast Salish. Because of the lack of extant garments from the early contact period, it was difficult to determine dress style change as it occurred among these two groups during the nineteenth century. The inventories provided data on the types and relative quantities of dress goods available to them, and written descriptions gave an idea of how the merchandise was being used. Inquiries into individual Native groups will provide a much more focused and specific understanding of them and their responses to the fur trade and will help eliminate the generalizations made regarding the impact of the fur trade on the material culture of Natives.