Articles

Museums, Visitors and the Reconstruction of the Past in Ontario

Abstract

Like many other heritage activities, community history museums in Ontario had a basis in antimodernist sentiment. These institutions served as spiritual guides that conveyed the values and identities of the community's founders. The image that emerged was one of a pre-industrial, rural, nineteenth-century society. The social groupings featured in exhibits were the Indians until they were displaced by civilization, the pioneers, and the Victorians. A similar approach was reflected in the development of collections and even in the selection of the museum buildings themselves: an attempt to preserve the rapidly-disappearing past. The need to attract provincial funding and broaden visitorship in the last fifteen years has led local museums to modify this tendency. Pioneers still abound but museums try to attract all of the community through the addition of special programming activities and the treatment of the "new" pioneers, the multicultural elements who have arrived since World War II.

Résumé

La nostalgie du passé est souvent à l'origine des musées d'histoire locale de l'Ontario, comme de beaucoup d'autres activités du patrimoine. Ces établissements marquaient un retour aux sources et devaient transmettre les valeurs et les vertus des fondateurs de la collectivité, en présentant la société préindustrielle et rurale du XIXe siècle. Les expositions illustraient la vie des Amérindiens jusqu'à l'arrivée de la civilisation, puis celle des pionniers et des gens de l'époque victorienne. La même optique, soit la préservation d'une époque à peu près révolue, présidait au développement des collections et au choix des bâtiments de ces musées. Au cours des quinze dernières années, la nécessité d'obtenir de l'aide financière du gouvernement provincial et d'élargir l'éventail de leurs visiteurs a toutefois incité les musées locaux à changer d'attitude. Les pionniers sont toujours le centre d'attraction, mais les musées cherchent aussi à plaire à l'ensemble de la collectivité en incluant une programmation spéciale et en accordant une place de choix aux« nouveaux » pionniers, c'est-à-dire aux éléments multiculturels arrivés au pays après la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Tourists to the Past

1 Not all foreign countries lie beyond our own shores; some exist on the other side of time. We view these lands according to our present needs and capabilities. Both tourists abroad and visitors to the past2 seek refuge in a place where authenticity3 and contrast to the everyday present define the ways in which "things are done differently there."4

2 Like many other heritage activities, community history museums5 in Ontario have a basis in antimodernist sentiment.6 Antimodernism is a response to the perceived negative qualities of modernism, including loss of a sense of community, alienation from the family, and lack of personal involvement in the production of primary goods such as food, clothing and furniture. This sentiment shaped the development of community museums in Ontario and continues to influence the presentation of the past in these places. Although recent trends in academic historiography and museology encourage community history museum activities toward more contemporary social historical themes and approaches to interpreting the past,7 and away from pioneer reverence and nostalgic recreations, these latter interpretations still dominate in products designed to augment visitor attendance. The persistence of these presentations can be understood as a legacy of these museums and their continuing social function as civic organizations.

A Potent Legacy: The Pioneer Experience as Antidote to Modern Life

3 When visiting history museums, prompted by a sense of modern alienation or nostalgia, a need to escape or a feeling of civic pride, tourists pick destinations created by individuals with similar motivations.8 In the face of postwar immigration, urbanization, regionalization, and the disappearance of farms, homes, local businesses and traditional institutions,9 the building of local museums10 was driven largely by fear11 of the loss of local character, and nostalgia for the idea of past values and past communities. As an observer of the 1953 founding of the Jordan Historical Museum of the Twenty explained:

The character of the area began to change rapidly after the two world wars. The older families, fearful for the future, and nostalgic for the past were eager to preserve their pioneer heritage."12

4 This pioneer heritage was usually identified in its material shape — the form manifestly disappearing from the landscape, and easiest to collect.13 Local history museums became known simply as "pioneer museums."14 Guided by the myth of the pioneer,15 advisers to those involved in museum-making reinforced the fundamental role of collecting and exhibiting pioneer objects to offset the malaise of modern life. At the first meeting of museum curators in Ontario in 1954, Dr. Louis Blake Duff, past-president of the Ontario Historical Society, described the pioneer period as a time "in which men and women had purpose, perseverance, thrift and sincerity, qualities not as prevalent in our own age."16 Miss Blodwen Davis's accompanying presentation "History at the Grass Roots," underlined the importance of collecting pioneer values. She identified these as "decision, effort and cooperation,"17 and saw them as an antidote to a modern age.

In contrast to a pioneer lifestyle, she added, "the whole trend of North American gadgetry is to make life easy and soft with as little work and as many possessions as possible."19

5 Public interest in preserving and recreating the past through the creation of community history museums flourished progressively in Ontario after World War II. Louis Blake Duff's 1954 dream to "pass some day through a succession of museums rising from Montreal to Windsor, from Hamilton to Fort William"20 was realized within three decades. The number of community history museums grew from about 40 to over 400, accompanied by substantial increases in staffing, museum programmes and capital and operating funding from federal, provincial and municipal levels of government.21 Initially, the material proofs of pioneer life were allowed to speak for themselves. Brief labels identifying objects with donors implicitly connected past and present through founding families. As private collections and historical society museums became more established into community institutions there was a paralleled push from the developing museological profession to incorporate relics into narratives that a general public could follow. The exhibit story-lines about the local past that developed were, not surprisingly, focused on the settlement period and told of local success and ingenuity, relying on extracted nostalgic, filiopietistic, and civic sentiments from the objects collected and displayed. The growing function of the community museum as a civic institution compounded the theme of pioneer virtue into a narrative linking honest struggle with civic success.

The Community History Museum as Spiritual Guide

6 Although rarely acknowledged by individual institutions in such terms22 the community museum in Ontario fulfils a fundamental role of moral and civic service. The moral motif that links the ideology of these museums is tied twofold to the idea of civicness; through objects the museum preserves and ratifies the values and meanings of the community's past and presents these to the community for its benefit in the face of the uncertainties of modern living. As A. C. Parker suggested in his 1935 Manual for History Museums, museums "visualize the past for the benefit of the whole community making the values of the past potent in the present, and available to all citizens."23

7 These notions have continued to the present day. In 1957, American museologist Dr. Carl Guthe told Ontario museum curators that the role of community history museums was to epitomize the local memory, and in so doing, stimulate interest and create goodwill among citizens.24 He underlined the civic importance of the local museum. Not only did it "furnish a field of reminiscences for old-timers," it also served as "a fund of comparisons for civic leaders," and "a source of pride and loyalty for the younger generation" including those yet unborn."25 In 1969, curators were informed by a provincial museum advisor that community museums had the capability to help modern man who, "feels unsafe as if drifting without an anchor ... realize a new spiritual foundation," by relating past and present in ways which would express "a continuity of such depth and meaning" that it would "appeal to the individual on the highest level of his consciousness and understanding."26 As a recent community museum guide to employees stated, "Museum work is a calling, a public ministry, a commitment to a better world through the enlightenment of the public."27 Even as she launched into a dialogue on the lack of social historical interpretation at community museums in Ontario, a recent critic acknowledged, "Certainly the role of history museums is to create confidence, reassure and create continuity."28

8 Community museums are still envisioned as spiritual conduits, transmitting the values of the past in a moral narrative29 to the present. Current museum statements of purpose confirm that these places serve by collecting, preserving and interpreting the past for the benefit of the present, with an emphasis on the founding and settlement of the community. In these mission statements the founding fathers or "pioneers"30 are memorialized to educate the public "for its betterment."31 This activity is a form of local nativism,32 and frequently those taking part in it have been long-standing community members and descendants of founding families, engaged by their participation in preserving their own personal pasts.33 The role of such museums fulfils the textbook criteria for defining folklore: they are places for amusement and escape, they validate culture, educate, and serve to maintain stability. As do myths, most community history museums in Ontario explain the present and make the unknowable future safe by reference to a knowable, archetypal past.34

The Rhetoric of the Past: Material Culture as History

9 What is that archetypal past? Based on collections' types and museum presentation style, tourists to Ontario's museums see that Ontario's past, beyond its military fortifications, is mainly a rural, domestic place. Despite differences in the local past, the attention to settlement and Victorian periods as interpreted through material culture, and the production of descriptive narratives based on similar kinds of artifacts, has produced a certain homogeneity in the presentation of the past in Ontario's community history museums. Historic villages (which never existed) and historic houses are characterized by a defined timelessness, usually situated somewhere in the nineteenth century. These are cultural re-creations, synchronic and largely depoliticized studies, centred on artisanal and pre-industrial modes of production. Ontario has few industrial museums, and no ecomuseums.35 With the exception of historic sites such as the Enoch Turner Schoolhouse, which depicts and discusses the issue of childhood and free schooling in 1848 Toronto, portrayals of social groups such as women, children, and First Nations frequently fulfil traditional stereotypes and beliefs about women at home, blissful childhoods and savage cultures. The metanarrative for museums with chronological galleries is the creation of civilization out of wildness, through local success and development, illustrated by improvements in material technology, the development of social institutions and the growth of the community. This is civic history at its most explicit, and few museums have challenged this narrative with stories of local contention, desolation or social struggle.36 Social issues such as industrial labour, cultural or racial conflict, suffrage, poverty, crime and so on are minimal in exhibits in these museums. Instead, one sees, even in local history museums with chronological gallery exhibits, mainly local culture in the form of three dominant groups: pioneers, Victorians, and Indians.37

10 Travelling over the museum landscape in Ontario, one is immediately struck by the overwhelming presence of pioneers. They are everywhere. Whole villages are stocked with them — and named after them — Black Creek Pioneer Village, Muskoka Pioneer Village, Lang Pioneer Village and Fanshawe Pioneer Village. Pioneers are the past in residence in 24 of 42 historic houses examined, and dwell in the primary sections of local history museum galleries. Based on these presentations we learn that pioneers lived in log cabins, and were in order of frequency of appearance in museums, United Empire Loyalist or British (mainly Scottish), Pennsylvania-German Mennonites, Quakers, escaped Black slaves, Irish or French-Canadian.38 With the exception of the latter two groups, the pioneers are chiefly Protestant. Pioneers worked industriously to "make do" and fashioned most of their material goods by hand. Most importantly, they were our community founders. The attributes associated with the pioneers are masculine, moral ones: self-sufficiency, industry, honest struggle, productivity and resourcefulness.39 Pioneers are most frequently depicted working the land, spinning, churning butter, or baking in an open hearth.40 These relatively poor folk, with their sparse homes in the wilderness, live in greatest contrast to those of us who dwell in the late twentieth-century. However, there is a species of wealthy pioneer, especially in the southern part of the province, known as Georgians, who serve to inspire us with their good taste in neoclassic or Regency architecture and furnishings.41

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 211 Succeeding the pioneers and in growing numbers are the "Victorians." Like the pioneers, this group is defined in exhibits less by a temporal period42 and more by its outstanding characteristics. These traits are shown to be in sharp contrast to the producer-ethics of the pioneers.43 Chief among these are a certain feminine social and aesthetic sensibility, expressed through restrained behaviour and rampant consumerism. Victorians are quintessentially middle class professionals. Unlike pioneers, they do not handmake fundamental items like candles. Instead they do "handiwork," a form of useful, artistic, leisure. They engage, for instance, in a seemingly endless production of needlework.44 They decorate interiors to a suffocating magnitude and have a particular focus on the parlour as a place of social importance.45 They incorporate a range of unwieldy gadgetry in their daily occupations46 and, unlike pioneers, seem to spend a good deal of time indoors, in various forms of elaborate dress.47 They are preoccupied with social ceremonies and rites of passage, such as christenings, weddings and funerals.48

12 The Indians in lesser numbers, that become completely extinguished by the pioneers, have no relationship to the pioneers or Victorians, or for that matter to most of the tourists.49 Indians are evidenced by the archaeological remains of their forbears, maps showing their original lands and migration patterns, artifactual vestiges of a lifestyle tied to the land, and discussions of myth and cultural practice. They are the savages that predate or are removed by civilization, and rarely surface again.50

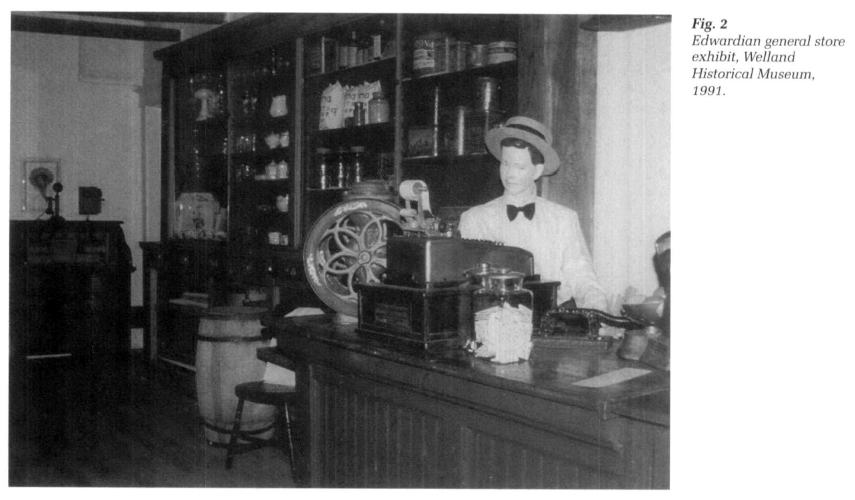

13 Finally, the others, the Edwardians, the soldiers and pre or early post World War I people, industries and organizations occupy a vague and diminished place in Ontario's past. Edwardians appear in much smaller numbers in historic villages or historic houses, populate local history museum streetscape and storefront exhibits,51 or linger in small showcases at the end of local museum history galleries.

14 These are, of course, conventionalized presentations, but they are soundly sustained by the policies, collecting, cataloguing categories, exhibits and interpretive programmes at Ontario's community museums. They are descriptions mediated by museum type and, for a number of reasons, are presentations in the process of change at many sites.

15 The status quo presentations of the past in Ontario history museums have been described here as a product of fear intersecting material obsolescence. That juncture also featured local initiative uniting with government grants to cover museum development or operating costs. In the process of salvaging threatened buildings and objects, there seemed to have been little opportunity or criteria, beyond the object being old, and fitting into a display or storage space52 to critically assess what should and should not be rescued. The result was the amassing of rambling collections in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, in less than desirable conditions, frequently under the direction of volunteers untrained in museum management. A consequence of this activity was the development of a museum professional organization, which along with academic institutions introduced certificate and degree courses in museum work in the 1970s and 1980s.53 With capital and operating costs escalating as museums established, upgraded, and moved from volunteer to professional management, a change of governance from historical societies to municipalities took place,54 accompanied by a growth in provincial advisory services and grants to community museums. Immediately following the introduction of the community museums' policy for Ontario in 1980, museums seeking operating support from the Province were required to meet a series of minimum operating standards to direct, and put an end to, the topsy-turvy growth of collections and museums that characterized the 1960s and 1970s, and to integrate the museums more fully into their communities.55

16 As a result of these influences, the three most fundamental changes in the operation of community museums in Ontario during the last fifteen years have been the improved care and management of collections, a shift from object-centred to community-centred approaches to operations, and a concern for historical integrity in the interpretation of the past at these sites. Tens of millions of capital dollars have been directed by federal, provincial and municipal governments to community history museums in the last decade to upgrade facilities for better management of collections and enhanced interpretation of these materials to the tourist. A heightened sense of responsibility to the community has generated a substantial increase in the production of school programmes, public programmes and special events, rotating exhibits and other activities designed to appeal to, and attract the public. In addition, museological literature and conferences have vigorously advocated for social historical approaches to studying the past.56 Museums are revising statements of purpose and altering their collections and portfolios of programs to address these concerns, which have been implemented where human and financial resources exist to address them. Curatorial recognition of the complexity of the past, and concern about the historically questionable portrayals that have prevailed in Ontario's history museums, has generated the introduction of social and cultural historical perspectives and themes into the museum narrative, perspectives which effectively subvert the pioneer myth and expose anxieties and profanities of the local past. In addition, this portrayal of social history is often projected into what one might call the modern age, the period after World War I. This revisionist work is an onerous undertaking, hampered by a shortage of resources to change traditional venues, difficulties in researching and interpreting social history themes with material culture,57 and the almost addictive nostalgic response to the past that museum visitors seem to enjoy.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Subverting the Pioneer

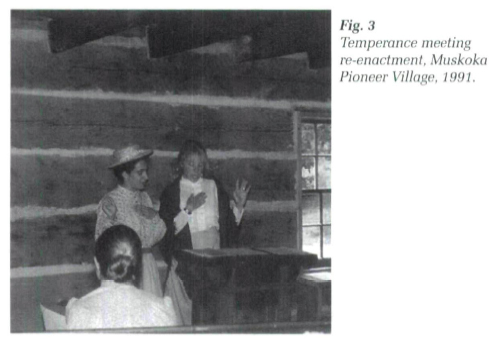

17 Doon Heritage Crossroads is a revised, former nineteenth-century pioneer village with a new cut-off date of 1914. Instead of inviting us to come back to a "better place in time," this museum's brochure warns us up-front about social and economic problems affecting rural Waterloo County at the dawn of World War I. Along with other museums such as Black Creek Pioneer Village, Muskoka Pioneer Village and Upper Canada Village, these once "peaceable kingdoms" are now interpreting alcoholism and temperance, women's suffrage, workers and unions, and personal bankruptcy on the family farm. This method of interpretation frequently takes its form in the use of isolated theatrical dramas implanted into the otherwise traditional daily portrayals at these sites.58 Collecting for this kind of interpretation of the past, at least as it has been compiled at Doon Heritage Crossroads, relies a lot more on oral, and documentary sources than material effects.

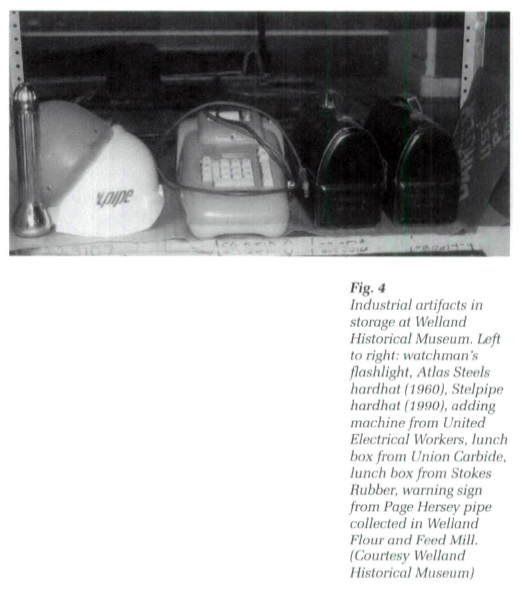

18 Gallery history museums are also investigating parts of the past previously neglected in both artifacts and story lines. Like many other social historical exhibits, the Halton Regional Museum's modest display in 1991 on childhood in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries looked to relevant scholarly literature and contextualized the local situation within that material. Thus the exhibit on childhood at the turn of the twentieth century examined questions about infant feeding and nourishment, infant mortality and the development of an industry and consumer market for specialized children's furniture, using local examples and materials. Interpretations of local industry look at the worker's perspective when possible, and again much of this involves new collecting of artifacts, documents and oral histories not previously collected in the spirit of the pioneer. For instance, the Welland Historical Museum's 1991 accessions included a Union Carbide lunch box, as well as many photographs and documents from heavy industries in the area that have recently closed their doors. The curator has also collected oral histories from welders concerning work on the Welland Canal. These industrial and occupational histories are communicated in the museum in other formats, such as a 1991 "Festival of Work and Labour Experience" where both retired and still active workers reminisced and shared their work stories and experiences. Other industrial history exhibits included a well-researched display at the Macaulay Heritage Park on the growth and decline of the canning industry in Prince Edward County. Interest in industry and occupation has been matched with attention to gender roles and local history. The Welland Historical Museum used interviews, photographs, and videos as well as artifacts to support a 1990 exhibit titled "Women Working in Welland," which examined women and work in local domestic, clerical and industrial jobs from 1850 to 1950. Likewise Brant County Museum's 1990 display, "Changes on the Domestic Front" and the Chatham-Kent Museum's 1989 exhibit, "A Woman's Work" looked at the changing role of women and work over the last century. The Peterborough Centennial Museum and Archives produced "Ordinary Women ... Everyday Lives," a 1989 exhibit on the challenges of researching women's history in Peterborough from 1850 to 1940. In the same year the Raleigh Township Centennial Museum examined the significance of Black women in the Black settlement of Elgin/North Buxton. Other social groups, such as brotherhood societies, have been the subjects of exhibits mounted in both historic sites and gallery museums.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 419 Resources for the mounting of well-researched history exhibits that vary from traditional portrayals are often found outside the museum's operating budget. Like the St. Mary's Museum's 1989 "Country Comes to Town" exhibit analysis of interaction between rural and urban area residents and businesses in the 1920s, Fanshawe Pioneer Village's research on Irish immigration relied on funding and staffing through student employment opportunities. As a curator at a museum in Northern Ontario explained, it was easier for him to find funds to double the museum space than have someone paid a salary to conduct local history research.59

20 Beyond a shortage of resources to conduct such work, contentious social history exhibits can put the local history museum's civil obligations at risk. A travelling exhibit from the Museum of the History of Medicine "From Plague to AIDS: Lessons From Our Past" mounted at the Halton Regional Museum, and that museum's accompanying display: "ADDS: Halton's Response" was blacklisted and actively boycotted by the Roman Catholic School Board in Halton, because it discussed safe sex rather than adopting the "Just Say No" policy of the local diocese. After much negotiation in order to retain the high number of Roman Catholic school classes scheduled to visit the museum during the same period as this exhibit, the museum agreed to close the exhibit during visits to the museum by these school classes so that students would not be exposed to the exhibit's message.60

21 The attraction of such new approaches to the past to visitors at Ontario's community history museums is unclear.61 The few studies conducted on tourist responses to social history interpretations in museums suggest that tourists are interested in recent scholarship that does not "require fundamental alterations in the museum or in its image as a nonthreatening, entertaining destination."62 Curators interviewed for this paper maintain that these exhibits lack popular appeal. Attendance was very low for the Welland museum's exhibit on working women, and surprisingly, since schools tend to be the most supportive market for these kinds of exhibits, no classes booked visits.63 The Peel Regional Museum's 1990 exhibit on the Great Depression in Peel had a depressing result — few came. The curator was informed that people in the community did not want to relive or revisit that unhappy period of time.64 The need to maintain and encourage high attendance figures does not seem to support energies directed toward the production of exhibits based on scholarly research of unpleasant or contentious local social or cultural historical issues. As the curator of Doon Heritage Crossroads pointed out, this museum's audience consists of three main groups, none of whom seem particularly concerned with these topics: conscripted schoolchildren, families who bring their children for a leisurely afternoon and seniors who come to reminisce.65 His observation is supported by a scholarly analysis of social history interpretation and the allocation of resources at certain historic houses and villages in Ontario. The study concluded that lack of resources restricts historical research and revision at these sites to some degree, but that a much greater factor is the need to provide history moulded to the interests and tastes of the modern tourist.66

The Affecting Past

22 Attendance is a key criterion used by community history museums to evaluate their performance in the community. Combined with increased operating costs (due in part to upgrading demands from the province in return for provincial grants), and a need to justify operations to local municipal councils that provide the bulk of the funding, curators have made great efforts to increase attendance at their sites through better marketing and the production and promotion of special exhibits and special events.67 Despite some recent efforts in researching and producing exhibits and education programmes using social historical themes and methods, these approaches are in little evidence as products targeted for tourists. Instead antimodernism and nostalgia prevail.

23 Indeed, an analysis of brochures from 92 community history museums in Ontario shows that the most marketed concept at these museums is the idea of escape through time travel to a better past. Themes and bylines such as "Good Old Times,"68 "Discover a Century Past,"69 "Come Back With Us,"70 and "Travel a Day in Time,"71 predominate. With the exception of Doon Heritage Crossroads visitor's guide, this idea of escape is paired with nostalgic images of the past. Here especially historic villages and houses parlay their rural presence and domesticity into images to lure the twentieth-century world-weary traveller back to a "special place in a special time."72 "As alive today as when Joseph's large, loving family called it home ..." calls out to us from the front of the Joseph Schneider Haus brochure beside a photograph of costumed young girls and their mother sitting in front of a lacy canopied bed. Museum brochure pictures show happy, healthy people engaged in domestic, agricultural or social activities. These are people the tourist would want to meet, activities we can join. Like the Joseph Schneider Haus, they invite us to "pull up a chair for a chat in the welcoming warmth of the farm kitchen."73

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 524 While historic house and village brochures describe inhabitants' daily activities, home interiors and architectural structures, in a narrative of pleasant escape to a "simpler life,"74 local history museums focus on particularly interesting or symbolic artifacts and galleries. Photographs or drawings on these brochures match the stereotypes of the past presented in the museum's interior. The most popular images (other than buildings) in order of use are: nineteenth-century agricultural activities (mainly horse-drawn ploughs), Victorian upper or middle class room interiors, spinning wheels or women hand spinning, weaving or carding wool, children playing, general stores, dolls, First Nations (not always positive images),75 steam locomotives and butter churns.

25 While describing the usual goings-on at these places, brochures often include information on special exhibits and special events, both designed to increase attendance and broaden the base of support for the museum. Of approximately 375 special exhibits mounted for tourist or holiday seasons in the 1989-90 period that were examined, descriptive displays on pioneer life were the most frequent topics, followed by exhibits on Victorian material culture. Not surprisingly, the most recurrent special exhibit theme at community history museums in Ontario is Victorian or pioneer Christmas, with descriptive exhibits of costume or fashion next in number. Children's toys and games follow closely in frequency of exhibit theme. As the most common artifact group for depicting or discussing childhood, these objects portray lighthearted versions of childhood experience in the past. Exhibits of First Nations follow next in number. Except those produced by the native-operated Woodland Cultural Centre, most displays are either archaeological or deal with First Nations at the time of contact, confining these groups forever to a pre-civilized past.76 Catchy names are used to attract the visitor to special exhibits: a display on women's underwear at the Aylmer and District Museum was coined "For Your Eyes Only."77 "Hot and Heavy" branded an exhibit on domestic irons at Black Creek Pioneer Village,78 and women's costume at the Champlain Trail Museum was labelled "Sugar and Spice."79

26 Special events are the most potent means of attracting tourists and increasing museum attendance. At some sites, such as the Markham Museum, such events accounted for over half tin; annual visitors in a year.80 An analysis of 352 special events (arid these are in addition to public programmes such as lectures, school classes, films and so on) from 88 sites shows these festivities to be places where the past is animated at its most accommodating. Although some museums feature historically appropriate entertainment for these events such as the Kettledrum performances at the John McCrae Museum, social history themes are not the primary focus of these festivities. Instead these celebrations bring together families and local traditional artisans in the joyful ways of the pioneer and Victorian past. A carnival of cooking, eating and drinking, domestic crafts, agricultural activities, music, and dance provide for a two-way celebration of the past, and a pleasant opportunity for the visitor to feel they have learned something.81 The events that take place are not necessarily contextually accurate. No re-enactments of Orange parades, which were held in many Ontario communities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are performed, for instance.82 Instead, antique car shows are held on the grounds of historic villages as at Doon Heritage Crossroads, children perform traditional fertility dances around a maypole outside the 1850s Joseph Schneider Mennonite farmhouse.83 and the Battle of Gettysburgh is re-enacted at the Pickering Museum Village.

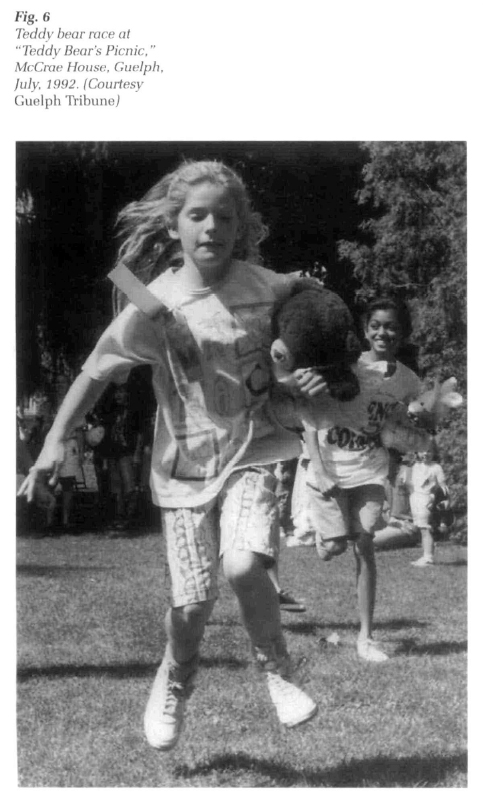

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 627 Sites also capitalize on contemporary religious and secular holidays for staging events. Several museums have Easter egg hunts, teddy bear's picnics and haunted Halloween parties for children. Mother's and Father's day celebrations feature crafts and exhibits of bonnets for mothers and military re-enactments and displays of horse-drawn vehicles for dads.84 The most popular theme for all special events is again "pioneer" or "founder's" days (70 pioneer day events held across 88 museums), followed by Victorian or pioneer Christmas (57 events at 88 sites). Victorian Christmas celebrations, as they have been perpetuated, seem most authentic to North Americans and museums find these festivities popular at a time of year when ritual and nostalgia are already in full force. Christmas exhibits with titles such as "A Hand-made Christmas," "Christmas in the Village," or "A Dickens of a Christmas," run for over a month at most sites. Against a background of pioneer hominess or wealthy Victorian interiors filled with swags, ribbons, decorated trees and exhibits of turn-of-the-century toys, visitors can drink mulled cider, eat gingerbread, participate in carol-singing, and fulfil their needs to balance the barren secularization of modern Christmas. Strawberry socials, garden parties and social teas are favoured summertime events, and Thanksgiving or harvest festivals populate the fall season.

28 Special events connect the local past and present much more candidly than exhibits at community history museums in Ontario. Instead of re-interpreting donated objects in a passive narrative or animated rhetoric of the past, at special events the historical interests and leisure needs of the present are matched with a range of local resources, to reproduce those aspects of the past which are most attractive to the tourist. Tradition and culture in the form of public performance, not curated history, predominate here, through crafts, music, food, and dance. Like museums, special events can be viewed as rituals of nativism and cultural regeneration, underlined by a shared understanding of what is culturally appropriate and authentic.85 This is heritage in praxis. Like most folk festivals, it appears to be also, in Dean MacCannell's sense of the word, undeniably antimodern. Perhaps this unabashed, decontextualized collage of ersatz history, folk performance and re-invented traditions is evidence of an ongoing need to create a social and cultural community identity. The pioneer remains stalwart throughout these activities, but with a new and curious companion.

Global Pioneers

29 Modern pioneers in the form of local multi-cultural groups have also taken up residence in Ontario's community history museums. Through exhibits in museums of the history and traditions of these groups, they become "traditionalized, valorized and legitimized"86 as part of the community. Concerning an exhibition at the Strathroy-Middlesex Museum on the local Portuguese experience, the curator wrote:

30 Perhaps, with a new generation of curators, and a new social gospel, the pioneer myth in Ontario's community museums is finally being replaced with one more compelling; that of a multicultural society in a global village.88 This concept still has much to do with fear of loss of identity, but in this new myth the distinctiveness and values of the local past are secondary to the cultural fabric and relativeness of the present. Embracing multicultural exhibits in which various local ethnic groups present themselves, where the historical storyline is ancillary to contemporary discussions of cultural tradition and expression, is very popular in these museums at present, perhaps more than the mounting of social history exhibits.89 Multicultural displays tend to express a celebratory flavour, cultural conflict is minimized in the outline of how these groups have contributed to the community.90 Aided by provincial monies under a "History of Ontario's Peoples" programme that emphasizes community multiculturalism, the community history museum in Ontario is able to expand its civic responsibilities into explaining the recent past in a mode of pluralist optimism for the benefit of the community's present and future. Hopefully, as the curator above noted, this work will also expand the museum's audience.

Reflecting and Affecting

31 There is evidence that attendance to community history museums is down.91 Questions about the attraction of museums, the potency of objects and narratives, in a postmodern, electronic world have been debated in recent museum publications and conferences.92 Some discussions have tried to delineate the differences between missions and methods of museums and the secular goals of the museum's more popular alter ego, the theme park. These exchanges have argued for the application of theme park methods to museum missions in order to keep the museum a relevant, popular social institution.93 If in a postmodern pluralist society a museum visitor sees that a "stuffed tiger is a stuffed tiger"94 and no more, if spinning wheels lose their semiotic powers as signs of simplicity, honesty and hardwork, if we are indeed "amusing ourselves to death,"95 what is the future attraction of the typographically based, object centred, didactic community history museum?

32 The canonical debate in museology which pitches the temple against the forum seems appropriate here.96 With the ambivalence of the author of that article who sees the temple within the forum, this one suggests that there is a place for all these expressions of past and present in the community museum, with apologies to no one. Here, in the ever-expanding definition of heritage, perhaps the community museum can be equally elastic, and reveal itself in its true colours — a civic convention, diagnostic of the local cultural fabric in a myriad of forms, rather than a purely historical institution. Considering the community history museum's pioneer legacy, civic obligations, competing functions, diverse clientele and limited resources, perhaps we should accept that the museum will collect not only history, it may also serve to celebrate the local community in ways that meet its psychic needs. As a tourist to Black Creek Pioneer Village penned in their visitor's book: "Thank you for the realism [sic] and the daydreams of what the world should be like."97