Articles

What to Wear to the Klondike:

Outfitting Women for the Gold Rush

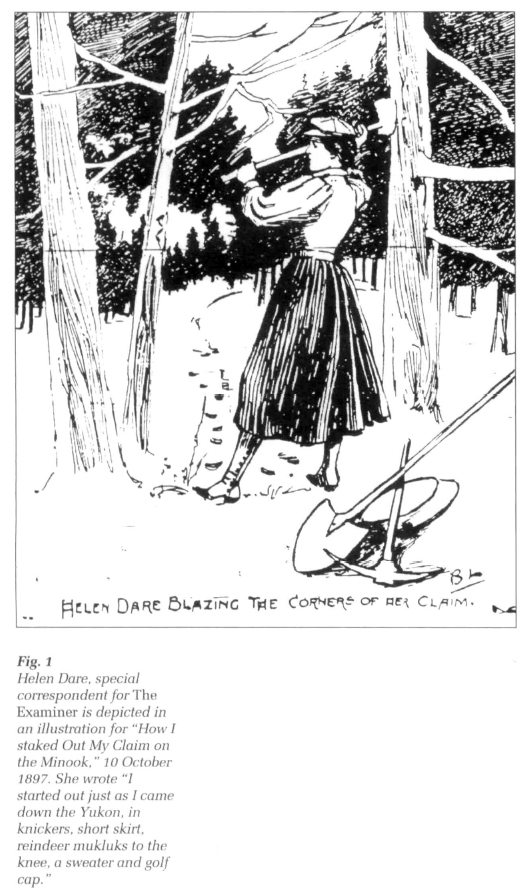

Abstract

The vast majority of women who went to the Yukon during the Klondike gold rush were not prostitutes and dance hall girls, but hardworking (if not mislead) women looking for wealth just like their male counterparts. Information about the role of these women indicates that at the time their image and their reality differed. Contemporary publications contained advice on what stampeders were required, and otherwise advised, to bring with them. The question of the appropriate clothing for women was a subject of considerable interest. Female prospectors tended to be depicted as "new women" who eschewed the conservative costume of the era. Irrespective of what had been worn to the Yukon, once women reached the territory they donned attire typically accepted back home.

Résumé

Lors de la ruée vers l'or du Klondike, la grande majorité des femmes qui ont pris la direction du Yukon n'étaient ni des prostituées, ni des filles aux moeurs légères, mais des femmes courageuses (bien que parfois mal informées) qui cherchaient à faire fortune à la manière des hommes. Nous savons aujourd'hui que le rôle réel joué par ces femmes différait de l'image qu'on s'en faisait à cette époque. Dans les publications contemporaines, les personnes tentées par l'aventure du Klondike trouvaient des conseils et des recommandations sur l'équipement à apporter. La tenue vestimentaire des femmes soulevait beaucoup d'intérêt. Les prospectrices passaient pour des « rebelles » qui rejetaient la tenue conservatrice de l'époque. Or, abstraction faite des vêtements portés pour l'équipée, elles revêtaient dès leur arrivée au Yukon la tenue classique des femmes de l'époque.

1 One of the first considerations for any stampeder going North after gold was discovered in the Klondike valley in 1897 was an outfit — a supply of goods which included foodstuffs, equipment and appropriate garments for the climate and terrain. The unsophisticated winter clothing of the nineteenth century made the climb up the steep grades of the Chilkoot, or along the precarious White Pass, more difficult for all stampeders, but the restrictive under-garments and the added burdens of heavy skirts made the journey even more problematic for women who represented between two and six per cent of Klondike hopefuls.1

2 Women's Klondike outfits reflected nineteenth-century expectations of women, so consequently what to wear to the Klondike presented a dilemma for women who saw the need to be comfortably, yet fashionably and respectably dressed. This quandary was complicated by representations in newspapers and periodical accounts that depicted women on their way to the Yukon dressed in calf-length garments or trousers, reflecting that journalists saw female stampeders as unconventional, and perhaps lending some credence to the already developing myth that female gold-seekers were all women of easy virtue. This image was later perpetuated by popular writers, academics, and even the Klondike Visitors Association itself.2

3 There is no doubt that Dawson was a male-dominated, male-centred society, but there were economic opportunities for respectable women, even if this employment was often in a traditional domestic setting. By the same token, cultural and societal demands of husbands and other men on the trail dictated that women wear what women in the south were wearing, with only minor exceptions. For example, Helen Dare, a special correspondent to San Francisco's The Examiner reported the plight of a Mrs. Barnes who had crossed the Chilkoot Pass wearing long skirts because her husband objected to short ones. She told Dare that the hems were frozen stiff and stood out like hoops.3 One male correspondent of the Seattle Daily Times described women's dress "going down the Yukon" and left no doubt as to what he expected of women's apparel on the trail. He wrote:

4 Some women, like those aboard the steamer Queen that left Victoria in early March, 1898, solved some problems but created others when they simply dressed like men in the typical miner's suit.5 Others felt compelled to provide themselves with a practical Klondike outfit and yet remain within the limits of Victorian respectability. Flora Shaw, the colonial editor of The Times, wore her canvas bloomers under her skirts, for example.6 Shaw had been sent to the Yukon by the newspaper because of previous experience reporting from the Australian gold fields, and was able to capitalize on the paper's political connections to make the trip to Dawson from London in three weeks. Investors in Europe were as eager as their North American counterparts to take advantage of the discovery.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 After the first shipment of Klondike gold arrived in Seattle and San Francisco in the summer of 1897, news of the strike spread rapidly across North America and on to Europe via recently established wire services, and the new transatlantic cable. A multitude of illustrations made possible by technological advances in photography also made the way south to generate excitement. Just prior to the gold rush, advertising had become an organized industry, and the Klondike offered an opportunity for the fledgling advertising agencies that had begun to emerge in North America. The coastal cities of the Pacific Northwest anticipated drat business would boom because of the rush, and there was considerable competition among Seattle, San Francisco, Victoria, and Vancouver to outfit the prospectors. Along with supply houses, and transportation companies, these communities distributed advertising pamphlets of every description. Commercial guides and government brochures, which contained advertising for all manner of goods, were readily available.7

6 Several of these Klondike guides offered specific advice to women travelling to the gold fields. These included Alaska and the Klondike Goldfields, by A. C. Harris,8The Goldfields of the Yukon by John W. Leonard.9 and The Chicago Record's Book for Gold-Seekers.10 These guides are notorious for their misleading information, but it is notable that they felt compelled to add some advice to women. These were commercial publications, designed for quick profit, so interest among women must have been substantial enough to warrant the inclusion of information especially for female stampeders.

7 Leonard, for instance, offered Ethel Berry's opinion on the "proposed feminine exodus to the north." Mrs. Berry was the wife of one of the lucky prospectors who had been in the Yukon when George Carmack had first found gold, and the Berrys had a rich claim on Eldorado. Ethel had gone Norm with her husband in 1897 on a wedding trip. She first advised Leonard's female readers "to stay away, of course. It is no place for a woman. I mean for a woman alone, one who goes to make a living or a fortune."11 But Mrs. Berry added that the trip and life in the Klondike would be better for a man if he had a woman with him.

8 Harris proffered advice from Mrs. Eli Gage, the daughter-in-law of the United States Secretary of the Treasury. Her husband was "prominently connected" with the North American Transportation and Trading Company, and Harris was quick to point out that Mrs. Gage was travelling North in some style, but her accommodations were "still far from being suggestive of the winter luxury of the elegantly appointed home in Chicago that [she] abandoned to share with her pioneer husband the rigours of the close season in the polar climate of Dawson City."12 Mrs. Gage's advice to women who contemplated a journey to the Klondike was that "they must make up their minds that they are going to live in a primitive way, and be prepared to endure hardships incident to the new Arctic country."13

9 Despite published warnings, women were generally ill-informed, and sometimes positively ignorant about the Yukon and the gold fields. One New York woman told Erastus Brainerd, an official of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, that she was off to the Klondike, and then enquired: "Can I walk to the Klondike or is it too far?"14 Many American women were surprised to discover that the Klondike was in Canada and not in the United States. Few had any real idea about the conditions they would encounter on the trip, but they were eager to find their fortunes in the gold fields. All, however, seemed to realize it was cold during the winter, and planned their wardrobes accordingly.

10 A Klondike outfit not only included clothing fit for an Arctic journey, but also mining tools, camping equipment, and cooking utensils, although unless she intended to actively mine a claim by herself or with a male (or female) companion, it is unlikely that female stampeders bothered with the requisite hardware and tools suggested by a number of the published guides. Canadian law required each stampeder to bring one year's supply, or 1150 pounds of solid food with her into the Yukon.15 What each woman took in the way of food varied with budget and taste, but there was a standard list of provisions which varied only slightly depending on who was offering the advice. Cost would vary, and outfits purchased in the United States were subject to Canadian tariff when the stampeder reached the border posts on the passes.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 211 In Canada, the T. Eaton Company had a two-page display in their spring and summer catalogue for 1898. The catalogue suggested provisions and groceries for one man for one year. Since there was no distinction between the amount of supplies required by women and men, this list would apply to female stampeders as well, although cynics might doubt that prostitutes and actresses would be subjected to the requirement. Such a conclusion is probably based upon the assumption that prostitutes and actresses would be subjected to the requirement. Such a conclusion is probably based upon the assumption that prostitutes and those who worked the dance halls were well provided for. They were clearly headed for the towns and not the creeks, and once they were installed in their places of business these women would not want from lack of supplies. The women who were not engaged in sexually related commerce however, and who travelled with family and religious groups, helped carry their necessary supplies across the passes. Ensign Rebecca Ellery of the Salvation Army, for example, described in her diary how she carried a 70-pound pack just like the men of the Sally Ann's Klondike Brigade.16

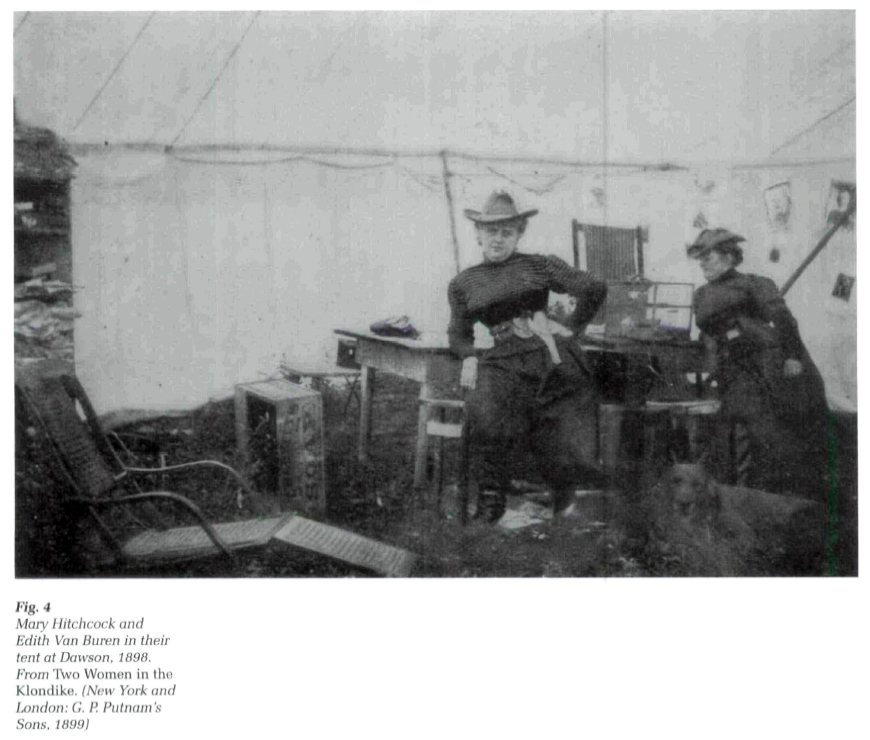

12 Eaton's list is especially valuable because it shows contemporary prices.17 The total cost of the goods listed was $66.68, but the list does not include mining or camping equipment, toiletries such as soap, or a first aid kit, or the cost of packing everything up. Neither, of course, does the cost reflect any fares or transport of goods, which would have varied depending upon the route taken. In addition to the cost of the supplies, a woman had to be prepared to haul this load on her back over the passes, or pay freight costs for a packer to carry it for her at 40 or 50 cents per pound.

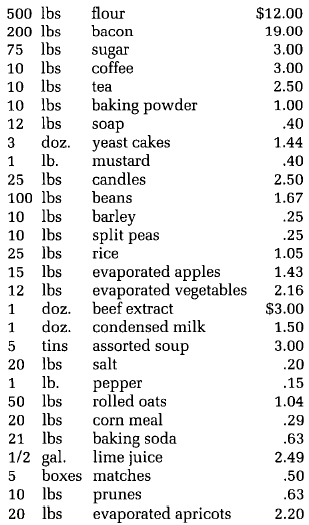

13 For foodstuffs, Eaton's suggested:

14 Based upon her experience in Alaska, Annie Hall Strong offered some "Hints to Women" in the Skaguay News about outfits. Since this list appeared in a Skagway newspaper, it would have little value to those planning the trip, but presumably small changes in the outfit could be made before travelling beyond the coast. Strong included some comments about foods. She called evaporated eggs a failure, and she condemned the use of saccharine as a substitute for sugar. "Take plenty of sugar," she wrote, "one craves it."18 Annie Strong also suggested the outfit contain some butter, 100 pounds of rolled oats instead of 50, lemonade tablets instead of lime juice, and both white and pink beans for variety.

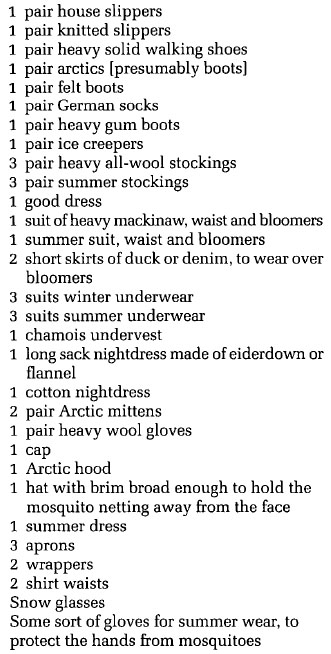

15 The clothing list paid careful attention to footwear (Mrs. Strong was adamant that the stampeder be careful that footwear fit well, and not be too large). But for some reason she neglected to include a fur wrap, parka, or heavy winter coat. Nor does she mention any housekeeping, mending, or toilet articles. Strong's list suggested:

16 The list of bedding included one piece of canvas, five feet by fourteen feet, one rubber blanket, three or four all-wool blankets, and one feather pillow. In contrast to Annie Strong's simple bedding were the sleeping bags designed especially for the Victorian Order Nurses (VON) who travelled north along the Stikine, British Columbia, trail with the Yukon Field Force a year later. These elaborate sleeping bags were made of canvas, lined with flannel and interlined with eiderdown. In Toronto, The Globe article of 19 April 1898 that described the nurses's outfits explained that "in shape they [were] not unlike a big old-fashioned bolster case, only that they button[ed] halfway down the length. With each bag [was] a hood of the same materials, and this [was] fastened across the face, so that the eyes and mouth were left uncovered."19

17 Annie Strong's outfit was similar to the one recommended by organizers of the Women's Klondike Expedition, a group organized by a Chicago lawyer, Mrs. Sarah Wright MacDannald. The New York Times reported rather facetiously that the group would not be all wearing bloomers of the same colour "like a Zouave brigade." Each individual member could exercise personal taste in her selection.20 A later New York Times item about MacDannald's group is more enlightening still, for it also provides an estimate of cost and weight of personal equipment required on the journey. These included: one pair of heavy wool blankets (10 lbs, $6.00), one oilskin or waterproof blanket (7 lbs, $3.00), one waterproof coat and hat (8 lbs, $3.00), one small pillow (1 lb., $1.00), two pairs heavy gloves (1 lb., $4.00), three suits of heavy wool underwear (7 lbs, $7.00), three suits of summer underwear (2 lbs, $3.00), one serge dress (1 lb., $3.00), and three shirt waists for summer (1 lb., $1.50). In addition, the women of the expedition were to take two corduroy or woollen dresses lined throughout with flannel, and with skirt above the ankle; a Hunter's or Norfolk jacket, bloomers or knickerbockers, together weighing 20 lbs. at a cost of $20.00. They needed two pairs of heavy boots with broad soles and low heels, a fur coat, cap and leggings — value $20.00 and weight of 20 lbs. Finally, two pairs of heavy moccasins, two wet weather moccasins, one sleeping bag, one heavy travelling rug, one pair dark sun glasses, two blanket wrappers or night robes, three muslin rappers or night robes for summer, a case of toilet articles, needles and sewing needs, four pairs of knitted woollen hose and four pairs of heavy lisle-thread hose for summer. These last items were estimated at 35 lbs but there was no cost given.21 As suggested in The Examiner of July of 1897 when it ran an outfit list for women, it was "astonishing how little people [could] comfortably get along with when they [tried]."22

Display large image of Figure 5

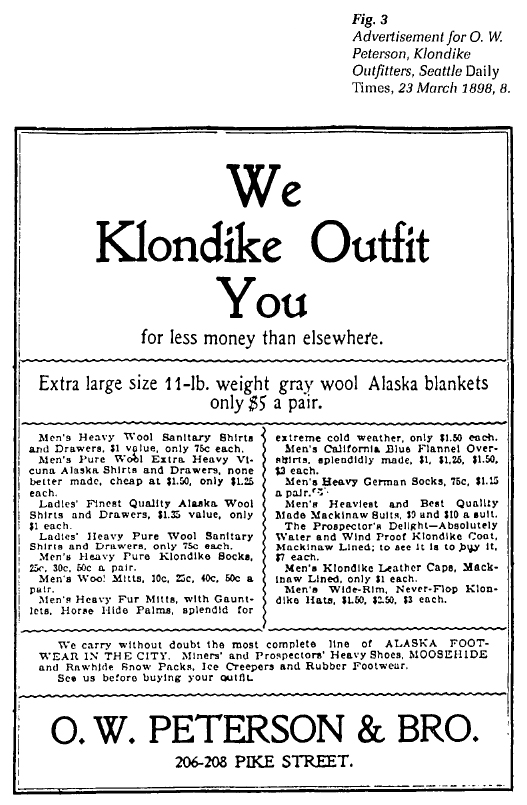

Display large image of Figure 518 Outfitters seldom advertised special Klondike garments for women, although John E. Kelly, the "Seattle Underwear Dealer," and O. W. Peterson and Brothers of the same city advertised undergarments for Klondike wear for both sexes. Peterson Brothers also advertised first quality Alaska wool shirts for ladies (at one dollar each) and pure wool "sanitary" shirts and drawers (at seventy-five cents each).23 It is possible these were small men's sizes and not clothing made especially for women, for as Ella Hall and her sister discovered when they arrived in Seattle on 7 April 1898, women "had a difficult time buying an outfit, as the outfitters told [them] that [they] must have fur suits, chamois vests, German socks, and moccasins; as they didn't keep ladies garments, [they] had to sell us men's."24

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 619 Men's outfits included dungarees, mining coats designed with storm collars and heavy linings, and Klondike shirts made of heavy woven or knitted wools. Nellie Cashman, already a veteran prospector when she went to the Klondike, told the Victoria Daily Colonist that her costume for mining was much the same as for men — long heavy trousers and rubber boots. The experienced Cashman suggested that skirts were not practical, but when she met with strangers she wore a long rubber coat, presumably to provide some sense of respectability.25

20 Edith Van Buren and Mary Hitchcock had more creative clothing designed and made for their trip north. They have been described as "big women" with "much embonpoint,"26 so it must have been some sight to see them dressed in blue and white knitted jerseys worn over corsets that were tightly laced. The women wore holsters containing large revolvers hanging from leather belts, blue serge knickers, short rubber boots and wide brimmed Stetson hats.27

21 The nurses of the VON had special costumes prepared for their adventure as well. At a send-off their new uniforms were displayed and received much attention from those present. On a mannequin was "exhibited a sample of their neat brown duck suits made with a short skirt with bloomers and gaiters in the style of a natty bicycle suit which they will wear when they walk these long, long 150 miles over mountain and swamp,"28 explained The Globe. Another figure displayed waterproof suits and tarpaulin hats. A third model wore a winter suit of heavy blue blanket, with large hood, lined with quilted silk. This was indeed a fashion statement, and quite a radical one at that, considering only three years before the Toronto newspapers had ridiculed female bicycle riders who had appeared in public in bifurcated garments. There was no comment later, however, as to how such a uniform was received in the Klondike creek settlements where the VON acted as public health nurses, or in Dawson where they worked at public hospitals and as private care nurses.

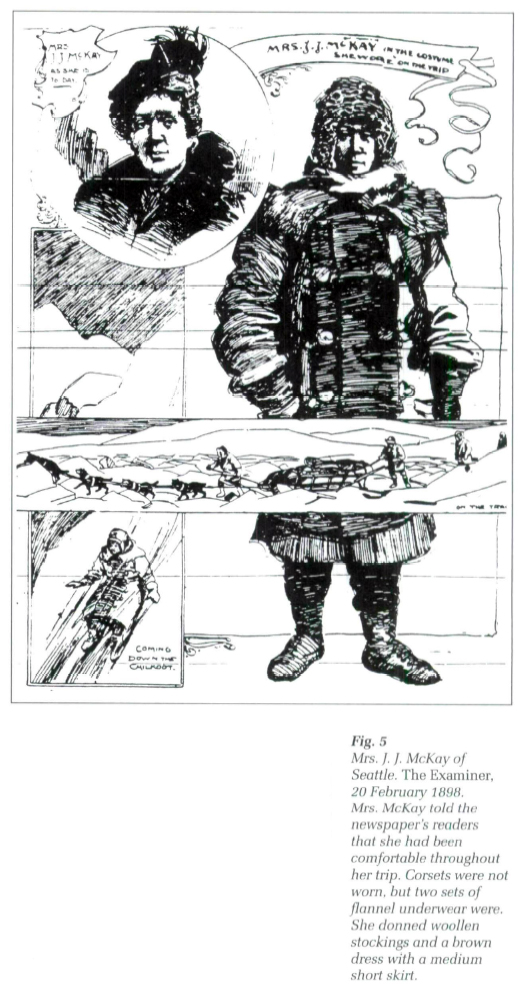

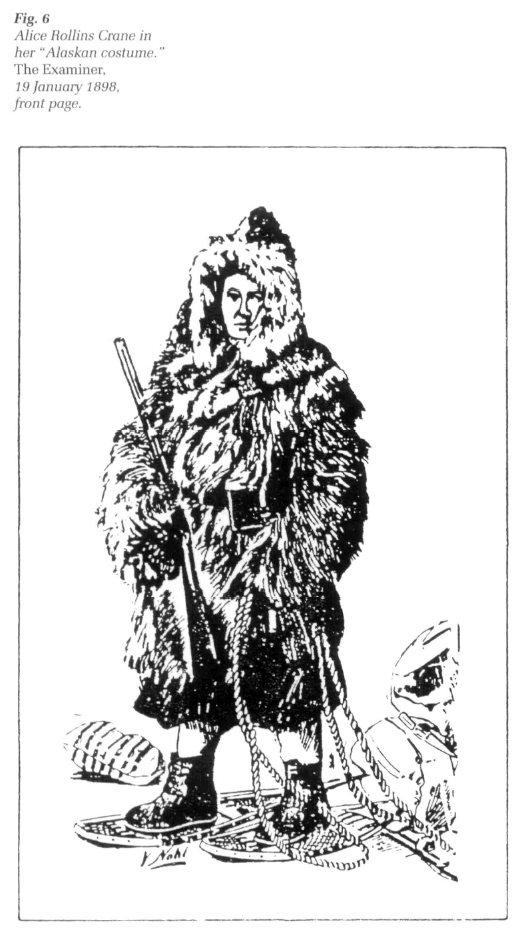

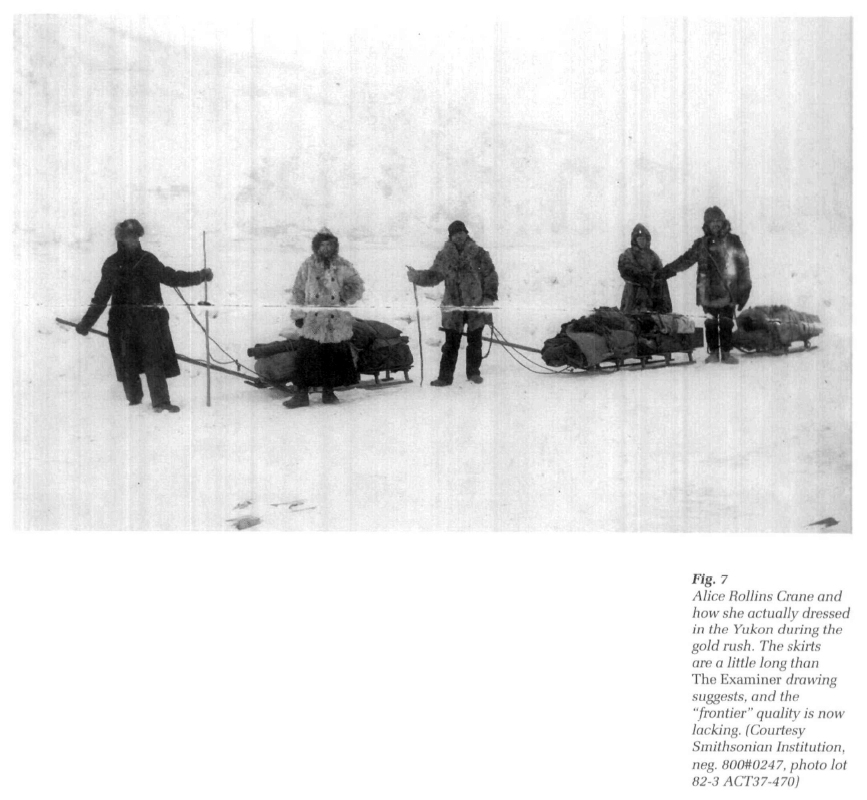

22 Mrs. J. J. McKay's travelling clothes were less spectacular. She told readers of The Examiner that she wore no corsets during the whole trip but had on two suits of flannel underwear, woollen stockings, a brown flannel dress, ordinary walking shoes and a cap. Mrs. McKay added a broad-brimmed hat when the sun was shining.29 A month before Mrs. McKay's revelation appeared, The Examiner had printed an illustration depicting the special Arctic costume of Alice Rollins Crane, a self-styled anthropologist who claimed to be on assignment from the Smithsonian Institution. In short skirts and snowshoes, carrying a rifle, and pulling a sled, Mrs. Crane appeared ready to take on the North. A photograph of Mrs. Crane taken after her arrival in the Yukon shows a much longer skirt, and lacks the frontier image so evident in the newspaper rendition.

23 Ernest Ingersoll advised in one of the early guides that the "new woman can straddle Chilkoot Pass in bloomers if they like, but in the chaste and refined society circles of Dawson and Cudahy, skirts are en règle — even if de trop."30 There was reason for this declaration, because another of the commercial guides reported that Captain Constantine of the North West Mounted Police was not very tolerant of women wearing bloomers or trousers of any kind, but that it would probably not be long before he would be enlightened by the "new women" and the "bloomer girls."31 Whether or not the "society" of Dawson or Cudahy was refined may be open to argument, but what is evident from photographs and written descriptions is that women in domestic employment or engaged in business wore "correct" if modified dress. They had tried to make some adjustment for the terrain and the climate within the bounds set by custom of the period, but not always successfully. Rebecca Ellery confessed to her diary that the outfits she and Emma Aiken had worn to the Klondike were the most foolish she had ever seen, and they were able to wear the same kind of clothing as anywhere else except in winter when they had to "bundle up." She added she had not "a thing fit to put on except what [she] brought on [her] own."

24 Despite the comparative isolation of Dawson, however, women were not cut off from fashion, nor from the desire to conform to the fashion of the day. Fashion papers may have arrived a few months old, but along with newcomers to the city, they brought news of the latest couture from the south.32 The cynic might suggest that it was the dance hall queens and harlots who were concerned most with fashion and what the Dawson Daily News called "other tricks for covering nature's defects."33 But there is no reason to believe that an interest in fashionable attire was restricted to female entertainers, or that prevailing customs were the concern solely of what passed for the upper echelons of Dawson society. It would be fairer to assume that all the women in Dawson cared about how they appeared in public, and how they appeared to the public. The difference was that some wanted to appear conventional while others wanted to be distinctive.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 725 An article on Klondike clothing in a special edition of The Klondike Nugget addressed the issue of short skirts in Dawson, and sums up the apparent result of careful planning and special outfits. It seems that

26 In the Klondike, because of the overwhelming male population, many women probably felt the necessity to make a conscious effort to maintain their femininity, and preserve an identity they perceived as correct. Conservative values dictated the behaviour and appearance of these women although their very presence in the gold fields illustrated the apparently new female spirit of adventure. Even those women who were "new women" viewed their appearance in light of social etiquette.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 827 From drawings and photographs it at first appears that women in Dawson wore shorter skirts than those in the south, and it is known that some women prepared shorter skirts for their outfits. This created the illusion that these women were more liberated than their southern sisters, and caused more than one writer to comment on the "lack of feminine vanity," in the Klondike.35 Yet consider the California schoolteacher who declared she "would have died before she would have appeared in them [sic] horrid skirts."36 The result of such attitudes caused Julius Price, the correspondent for The Illustrated London News, to comment that the many smartly-dressed women in Dawson looked strangely out of keeping with the surroundings,37 which is curious because when Price actually depicted a woman in Dawson in his paper, he drew her wearing a calf length skirt. Whether this was just wishful thinking on Price's part, or simply part of the effort to glamourize the whole adventure, is unclear and marks women's dress, like the assumption that all the women in Dawson were prostitutes, as yet another contrast between the myth and reality of the gold rush itself.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 928 It seems more likely that in Dawson skirts were simply pinned up to prevent hems being caked in muck from the quagmire of Dawson streets, or that if women wore bifurcated garments of any kind in public, they wore them hidden by voluminous skirts. If they were so bold as to wear trousers it was out on lonely creeks or in the privacy of their own cabins. But it is significant that more than one woman recorded she did not change her way of dress in any particular way once she realized it was not necessary,38 suggesting that no matter how liberating the gold rush situation may have appeared, whatever women wore to the Klondike, when they finally got there, the conservative clothing of the south was proper attire on the northern frontier.