Reviews / Comptes rendus

University of Winnipeg, A Winnipeg History: The Art of Marie Guest, 1880-1966

Sarah McKinnon, Art History Professor, University of Winnipeg, and the students of Art History and Exhibition Practice (1990-1991 course)

Claudine Majzels, Art History Professor, University of Winnipeg, and students

Sarah McKinnon, Claudine Majzels and students

Catalogue, 20 pp., edited by Claudine Majzels, with input from Professors McKinnon and Majzels, and students. Produced with financial assistance from The Manitoba Arts Council.

11 March to 6 April 1991

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 11 A Winnipeg History: The Art of Marie Guest, 1880-1966 was produced when two art history professors at the University of Winnipeg offered an ambitious and experimental course designed to give third-year university students an opportunity to conduct primary research and to assist in mounting an exhibit. The subject was Marie Guest, a Manitoba artist whose work was highly acclaimed from the 1920s to 1940s, but who was never accorded serious recognition in the annals of Manitoban or Canadian art history.

2 The impetus for the exhibit arose by chance while Professor Majzels was house-hunting. She walked into a home, and as she recalls, "encountered somebody whose presence was displayed on the walls." It was mostly the historian in Majzels who was impressed with the more than 60 paintings in the home of Mrs. Hessie Guest, daughter-in-law of the artist. Majzels recognized the tremendous research potential of such an extensive collection. In addition to the framed paintings, there were dozens of unframed works and sketchbooks, as well as metalwork and jewellery by the artist, and Guest's scrapbooks and photographs. As it turned out there was also excellent potential for research with family members and friends who had known the artist and who were living in Winnipeg.

3 As Majzels talked with her colleagues in the history department at the University of Winnipeg about her excitement in pursuing research on Marie Guest, the idea for an experimental history course evolved. She and Professor McKinnon decided that the course should include primary research on the artist, which would then be presented in an exhibit based on archival evidence. With access to such a remarkable collection of material history and people who had known the artist, there was an ideal situation for an enriching learning experience for history students. The project also created the opportunity to conduct and present to the community a previously unwritten chapter of Manitoba's social history.

4 The 12 students who joined the experimental course set out to discover all they could about Guest. They conducted their research by obtaining documentary evidence from institutions throughout Canada, through oral history interviews and by searching through archival newspaper and textual record collections. The class compiled an impressive body of data on the artist from primary sources and then participated in mounting a representative exhibit of the artist's Winnipeg work.

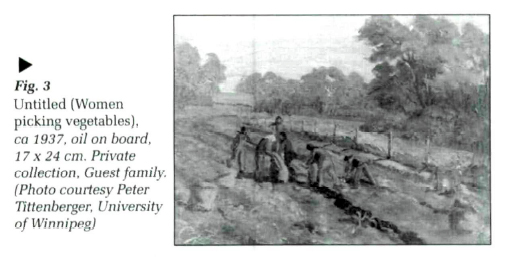

5 The exhibit brought together an interesting collection of paintings by Marie Guest. The 40 hanging works spanned the late 1920s to the early 1950s. As suggested by the exhibit title, the works were chosen in part for the story they told of life in Winnipeg during this period: the North End open-air markets; familiar cityscapes; leisure scenes at the lake; life in rural areas close to Winnipeg; Manitoba forests; and typical vacation spots along the warm southern U.S. coastlines. The exhibit revealed the range of the artist's themes, taking a social history approach which was developed through the choice of exhibit works, catalogue content, the inclusion of memorabilia and the exhibit tours and presentations.

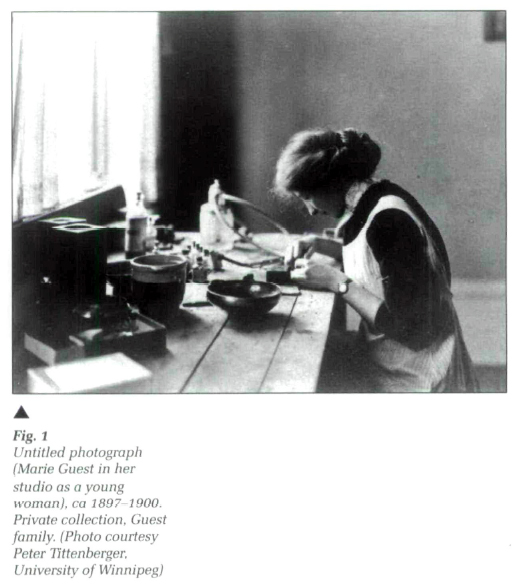

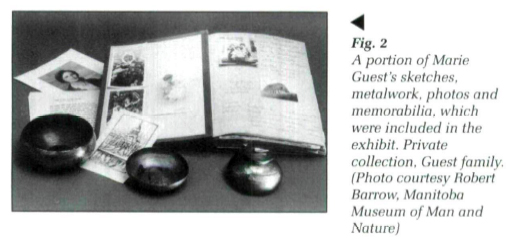

6 There was a major component of the exhibit that revealed something of Marie Guest's personal character and strengthened the social history approach of the exhibit. A large photo of the artist as a young woman, shown working in her studio on a copper piece, filled one entire wall of the gallery (Fig. 1). The photograph gave a strong sense of the dedication of this solitary young woman at the beginning of her career and seemed to invite the viewer to consider Guest's life as an artist. Central to the exhibit was a large case that exposed some of the more personal work by the artist and glimpses of her personal life. It contained jewellery designed and crafted by Guest, a copper box with a bullet handle, as well as sketchbooks, photographs and poetry created and used by the artist as reference material for her paintings. The case also included personal mementoes kept by the artist, such as her wedding and family photographs and a scrapbook (Fig. 2).

7 It is difficult to evaluate the success of the Marie Guest exhibit separately from that of the course, since the objectives for both were so closely intertwined. The professors were concerned with the pedagogical benefits that might be gained by the students through conducting original research, considering how historical interpretation and memory function, and concretely applying art history research. They were also aware of and motivated by the opportunity of bringing a talented and forgotten female painter to public attention.

8 There are certain difficulties inherent in attempting to interpret any subject as a group project. The interpretations of Marie Guest's life and work that I encountered in talking with the professors and students (and reading their reports) were as varied as the numbers of interpreters involved. I think that this range of perspective led to an exhibit without a strong singular analysis of the artist. Since the research was carried out by many individuals, neither professors nor students had an overview of all the material complete enough to probe the artist's character and paintings at a deeper level. However, this was an unavoidable situation as the evidence-gathering was designed as a group project and was further constrained by the time limitations — the exhibit opened only six months into the research process.

9 Another weakness of the exhibit was that while it showed a great deal of the artist's work produced in Winnipeg after her marriage, it showed only two paintings from Nova Scotia, where Guest lived for most of her first 39 years. The social pressures that the artist experienced once she moved into married life in Winnipeg were considerable. She ceased all painting for six years during which time she lived with her in-laws, gave birth to her two children and expressed disillusionment, if not depression, with painting her new environment. The exhibit did not address the artist's life in Nova Scotia in more than a cursory manner. It would have been interesting to have had some of her earlier works available for comparison. They may have revealed something about her very different lifestyle as an unmarried female artist and possibly her different approach to her work prior to marriage and move to Winnipeg. There is still a need to research the artist's birth family and early training, her artistic development and the influences that led to Guest's choice to marry when it meant leaving behind her support network. This research would address some of the questions that remain.

Display large image of Figure 2

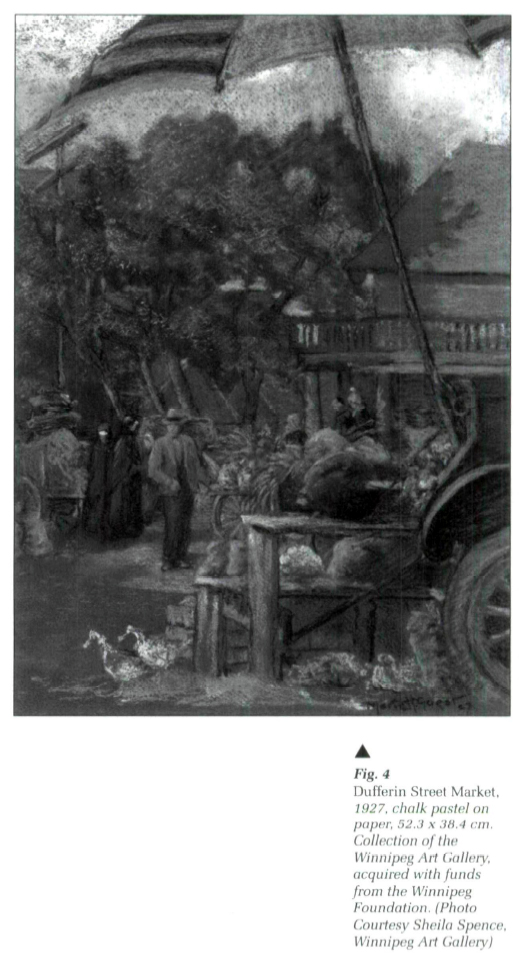

Display large image of Figure 210 There may never be another exhibit ol Guest's work in Winnipeg. Marie Guest was never interested in commercial success. She priced her works so highly that few of her paintings sold. Only one work is currently held in a public institution in Manitoba, The Dufferin Street Market (Fig. 4). The extensive family collection of Marie Guest's paintings, scrapbook, photographs and other personal belongings are now being dispersed to various family members. One would hope that some of the works by this interesting figure in Winnipeg's history will make their way into Manitoba's public collections.

11 While the exhibit, the catalogue and the related interpretive programs presented a great deal of information about the artist and the community in which she lived, they raised more questions than they answered. This does not diminish the value of the exhibit, but rather highlights the difficulty of obtaining swift results from primary sources: the Winnipeg research proved most fruitful, but the correspondence sent to institutions throughout North America was not as productive, despite the enthusiastic support from many of those contacted.

12 The exhibit did succeed in presenting a large number of works by Marie Guest to the Winnipeg audience. The students in the course expressed the difficulty of the group research and exhibit development process, but unanimously agreed that they would have missed the learning experience. Marie Guest's work was revisited and her contribution to Winnipeg's social and art history has come partially into public consciousness, at least in Winnipeg. One would hope that the work begun by Majzels, McKinnon and the students may encourage a similar course or research project in Nova Scotia, where Marie Guest spent the first half of her life. The life of this forgotten artist can reveal valuable insights into the lives of many women artists who, like Guest, led productive lives as artists, though their stories remain untold and their works unseen.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Curatorial and Primary Research Statements

SARAH MCKINNON

13 The current exhibition grows out of an experimental art history course in which the students have been able to further their academic art history education by means of practical training. In addition to the historical research methods they have learned, they have also been exposed to "hands on" aspects of exhibition curating, installation, conservation, design, publicity and art education.

14 A series of seminar workshops given by professionals in these fields has allowed the class to experience and participate in the practical aspects necessary to transform their research results into a public exhibition. This training has been particularly valuable because we no longer offer Museology at the University. Our experimental course has supplemented and strengthened our art history major by encouraging students to see the value of the application of their art history studies. They have learned how to communicate the results of their historical research by weighing the issues of exhibition preparation, topics such as visual impact of exhibition design, environmental considerations in displaying works of art, effectiveness of publicity and written educational materials, technical details of art conservation, monitoring gallery space and successful oral presentations to varied audiences.

15 Thus the Gallery has provided an opportunity to expand offerings in art history and to integrate practical experience into our teaching. It, in effect, has given the students an additional classroom, one which has increased their appreciation of the use of art historical research. In addition, because of their efforts they have helped to bring to public attention the works of a long-neglected painter. Undoubtedly the art of Marie Guest will now be appreciated by many new viewers as a result of this exhibition.

CLAUDINE MAJZELS

16 During this experimental course, the results from our research work only very gradually emerged. This was somewhat anxiety-provoking for both teacher and student, but thrilling as well. We all emerged from that experience with a vaguely unsettling feeling that we still did not know all that much about our subject, having been so closely focussed on the minutiae of provenances and dates. In that observation lies the truism regarding all historical and intellectual pursuits: the more you know the more you realize how much more there is to know. Another implication of our work in the areas of archival research and oral interviews was the inescapable subjectivity and the continual transformation of the evidence under the force of interpretation. That these concepts were actually "lived" by each student was a unique and valuable aspect of the course.

17 All through the year we were developing the concepts of interpretation and memory, and the idea of a process in conceiving history and how it is written, how works of art become public or remain hidden, how artists' reputations are made, how society conditions our expectations. Marie Guest appears to have gained a reputation as "a lady and a eccentric," and therein lies the key. If she had been only the first she would never have been an artist, and if only the second perhaps an artist, but not a "lady." She was both, by birth and education, and only because she had the money to be an independent spirit. Others less fortunate embraced poverty or commercialism, fuelled themselves with ambition and hard work and made it into the history books. Basically, Marie Guest just didn't need to or even really want to. Perhaps she didn't think she ought to want to. Perhaps she didn't know how much she could want to.

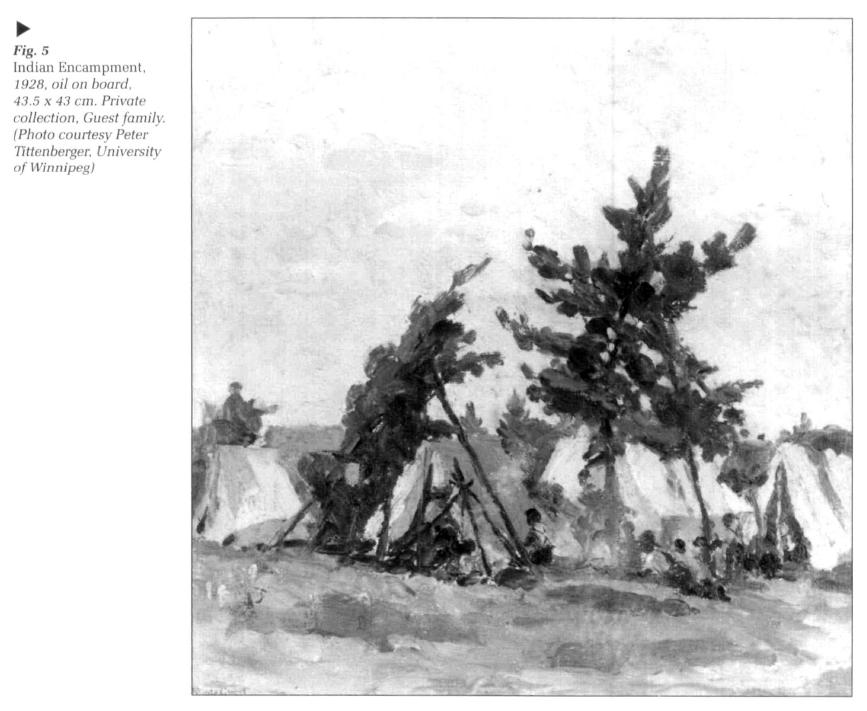

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 418 Hessie Guest tells a story about her mother-in-law: how one evening at the lake the supper had to be made and there was no help in the house: so Marie, who had suddenly been taken by an urge to paint a bunch of sunflowers from the garden, offered Hessie the painting of a picture in exchange for the preparation of the meal. For Guest it was not the material object that mattered but the process of making, the act of painting itself. She was fortunate that she could find herself in art, that she could afford to be introspective and independent, a wife, a mother, a traveller, a poet and a painter. The poetry is sentimental, the paintings are often derivative and the brushwork somewhat awkward, but the creative urge is there, the knowledge of Impressionism, and the awareness of Expressionism, in the style of the Canadian avant-garde of her youth. She remains rooted in representation, and her subjects, which are rarely adventurous, with the exception of her studies of ordinary women in the market stalls, fields and native summer encampments in and around Winnipeg. Guest has her place in the historical scheme, as do so many other women artists of the past too compromised by their gender and position, whether too far up or too far down the social latter, to realize their identities.

19 Together in this class we explored the life and work of Marie Guest and it was die process of that exploration that really mattered to us.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5Marie Guest: Biographical Overview

20 Marie Guest was born in Oxford, Nova Scotia on 21 April 1880 as Marie Olivia Hewson. The Hewsons were a family of means who owned a textile factory. Guest travelled to Europe with her family at the age of 16 at which time she decided to pursue artistic training. She began her art studies at Mount Allison Ladies College (Sackville, New Brunswick) in 1896, followed by training in watercolour painting and crafts at the Eric Pape School of Art (Boston, Massachusetts) and life drawing classes at the Art Students League of New York. She travelled to Europe again in 1913 and studied with Frank Spenlove of the Royal Academy School (London, England) and then sketched for the summer in Brittany, Holland and Belgium. After returning from Europe, she exhibited five paintings in the Royal Canadian Academy from 1913-1918. Guest pursued a teaching career from 1915-1919, first at the Women's Art Association in Ottawa and then at Mount Allison Ladies College. During the summers, Guest continued her own training with Charles Hawthorne in Provincetown, Massachusetts and in the DuMonde Summer School (Cape Breton, Nova Scotia).

21 Guest's marriage in 1919, at the age of 39, occurred as she was beginning to gain a profile in North America as a serious painter. Her adjustment to life in Winnipeg seems to have been difficult. Guest spoke of her aversion to painting the prairie landscape, but the transition to life in Winnipeg went deeper than differences in terrain. Guest was an unusual woman for her time, having neither the knowledge nor the desire to learn housewifery. For her husband's prominent and conservative family, this behaviour seems to have been viewed as somewhat strange. When Guest returned to her artistic work in 1926, her days revolved around painting: in summer she painted at her Victoria Beach cottage; in spring and fall on the edge of the city which she reached by taxi; and in winter in her living room. She employed a housekeeper much of the time to look after the demands of her home and family in order to dedicate herself to painting.

22 Guest was one of only several female painters in Western Canada working in oils in the 1920s and 1930s. She was fascinated with the rural areas on the edge of Winnipeg and painted some interesting studies of field labourers, native encampments near Lockport (Fig. 5) and women of various ethnic backgrounds. She attempted to capture the essence of her subjects through experiential means: her desire to experience what she was painting caused her to do such things as lashing herself to a wharf in preparation for her painting, Rider in the Storm. Guest did develop a support group of artist friends in Winnipeg who shared common values. Alison Newton, Lynn Sissons and Georgie Wilcox exhibited with Guest and they also supported one another in their day-to-day artistic work. Marie Guest was an interesting woman of her time who combined life as an artist with marriage and motherhood.