Reviews / Comptes rendus

Here's To The Roarin' Game: An Affectionate Look at Curling, Canada's Favourite Sport

Steve Prystupa, MMMN

Denis Lafreniere, MMMN, and Jim Sproule, Manitoba Curling Association

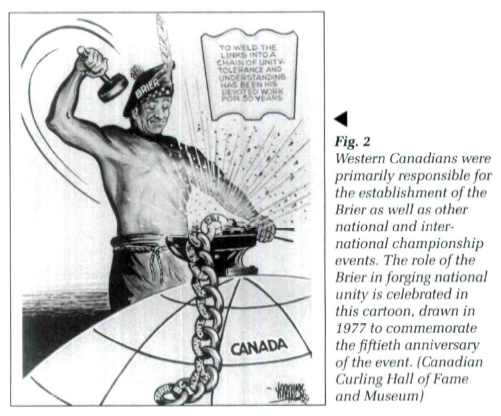

Tom and Ann Fisher, Canadian Curling Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc.

David Hopper, MMMN

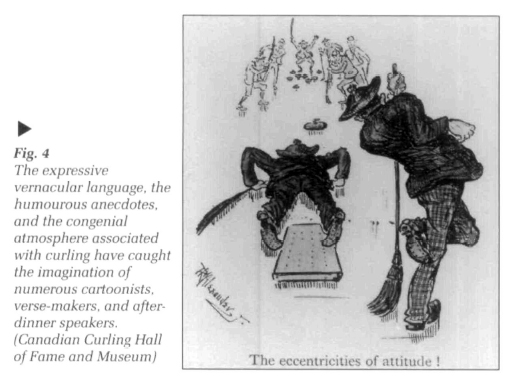

1 Between 23 March and 31 March 1991, both the ladies' and men's world curling championships were held in Winnipeg. As a salute to the events the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature prepared a free-admission exhibit on the history of the "roarin' game." The exhibit ran from February 22 to April 7. It drew between 4000 and 5000 viewers, an unusually large number for a production in Alloway Hall.

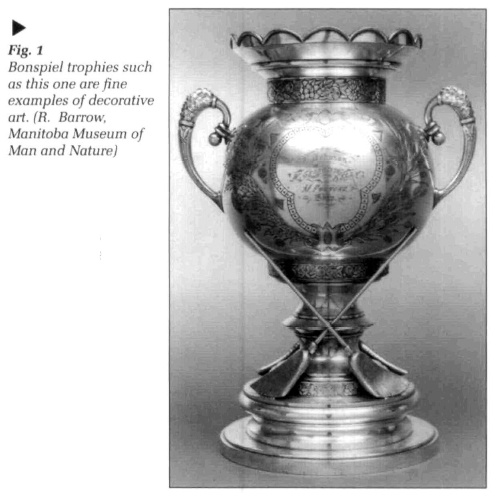

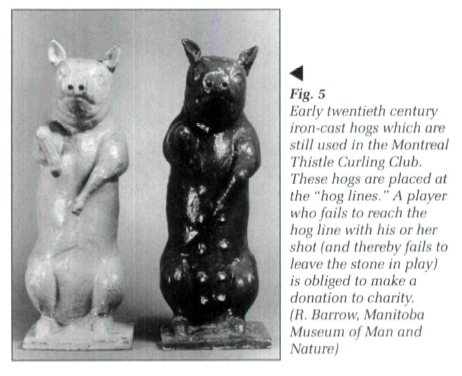

2 On display were over 300 items related to curling. Among them were traditional bonspiel prizes such as trophies, plaques, clocks, lamps, and serving trays; souvenir objects such as pins, banners, and ribbons; items of apparel including sweaters, spats, coats, and tam-o'-shanters; artists' or craftsmen's reproductions of curling scenes through paintings, carvings, photographs, film clips, and other media; pieces of curling equipment such as brooms, shoes, crampits, hacks, and rocks. Some of the items came from the Manitoba Museum's own collection; some came from Winnipeg curling clubs or curlers; and a large number came from the Canadian Curling Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc., which has a collection that is located in Montreal and managed by Tom and Ann Fisher.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 The main story line of the exhibit was articulated succinctly but attractively on large, accessible display panels, and it can be summarized here. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries the modern sport of curling was developed in Scotland. In the 1800s middle class Scotsmen transplanted the game in Canada where, for environmental as well as social reasons, it flourished as it never had in the Old Country. It did so especially in the Canadian Prairie West.

4 In this region, after the 1880s, for three or four months each year the curling rink, which was often under the same roof as the skating rink, was the most important social centre in hundreds of small communities. In this region also, especially though not only in large cities, individuals such as Bob Dunbar, Gordon Hudson, Cliff Manahan, Ken Watson, and Ernie Richardson studied and practiced curling as seriously as any professional athlete studied and practiced a sport. In the twentieth century they taught Eastern Canadians, Scots, and people around the world how the roarin' game could and should be played. They did so primarily through the national and international championships that Western Canadians were instrumental in establishing after the 1920s.

5 Meanwhile, across Canada people of all classes, of both genders, and of many different ethnic groups began to curl. Today, late in the twentieth century, curlers assert that theirs is Canada's favourite participant sport. There is no conclusive evidence to prove this, but the claim rings true because those who curl are young as well as old, female as well as male, poor as well as rich, disabled as well as able-bodied.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 36 The exhibit was informative and attractive for a number of reasons. Only two of the most effective and appealing features will be mentioned here. One was the use of cartoons and photographs to draw attention to the laughter that is so pervasive around curling games, most of it stimulated by an unconscious awareness of how absurd yet how interesting human beings are when they lose themselves in what they are doing. The second was the use of volunteers as guides. The organizers of the exhibit wisely took advantage of the fact that Winnipeg is filled with people who know curling. These people know how it feels to throw or sweep a stone. They are aware of the history and the folklore of their sport. They were able to describe, for example, how rocks were delivered when crampits were used instead of hacks, or what actually occurred when Bill Walsh made "the greatest shot in Brier history" at Moncton in 1956. And these guides were not clockwatchers. They were excited about their contribution to the exhibit, and grateful for opportunities to answer questions.

7 Two disconcerting aspects of the production were the omission of dates from some of the labels that described objects, and the failure to encourage viewers to move in a particular direction. Visitors to the exhibit could not help but learn a great deal about curling. However, they could easily fail to acquire a clear understanding of how the game changed over time, and of how it was played during a specific era.

8 A more important criticism of the exhibit is that it was entirely visual. The sounds of the sport were not present at all. Yet the sounds are distinctive — corn brooms pounding the ice, a skip yelling instructions at the top of his or her voice, one rock knocking into another — and over the centuries they have attracted thousands of participants and spectators. A sound track and stereo speakers might have been used to remind visitors that curling is heard as well as seen.

9 These criticisms are meant to suggest only that the exhibit could have been better. But it had many more strengths than weaknesses. It deserved the large audience it received in Winnipeg, and I hope that Manitoba Museum's current efforts to create a travelling exhibit will make Here's To The Roarin' Game available across the country.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4Curatorial Statement: Here's To The Roaring Game: An Affectionate Look at Curling, Canada's Favourite Sport

10 The recent curling exhibit at the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature evolved as a conscious effort to capture some of the limelight of the World Curling Championships that were hosted by Winnipeg in 1991.

11 The venue was very appropriate. To a large extent, Winnipeg has spearheaded the development of national and international curling since the turn of the twentieth century. The exhibit also offered a unique forum for the Canadian Curling Hall of Fame and Museum in Montreal. Since 1974, Tom and Ann Fisher have assiduously collected Canadian curling memorabilia. Working as volunteers, they have put together a remarkable collection of artifacts and documents which not only trace the history of the game, but also lend themselves to depicting important facets of Canadian social and cultural life. With the help of curling community contacts such as Jim Sproule and Denis Lafreniere, important finds were also made in the local curling clubs of Winnipeg and rural Manitoba. The curling rink has been a vital social centre in most prairie communities since settlement began.

12 Photogenically, the collections that were discovered were a curator's and designer's dream — curious old wooden and granite "stones," old "cowe" brooms, clothing and mementos spanning the last two centuries; historic photographs and art works highlighting the human interest of the game; the personal possessions of curling heroes; an illustrious array of national and international trophies and numerous examples of contemporary popular culture. The bunting and banners used in the rink and artistic recreations of actual game settings immersed the artifacts in their own authentic environment. The storyline was interlaced with excerpts from the fertile corpus of curling folklore — colourful vernacular expressions, humourous anecdotes, songs and poems going as far back as Robbie Burns. Old-timers who know and love the game were recruited as volunteers and served as tour guides through the entire six-week term of the exhibit.

13 All in all, the exhibit captured the charming social atmosphere of the game from its authentic Scottish roots to its contemporary cosmopolitan flavour. It would have been foolish not to incorporate these attractive selling points into the exhibit. However, a deliberate effort was also made to go beyond the festive and evocative elements and make meaningful statements about Canadian class differences, gender politics and ethnic relations. Historians like Peter Bailey,1 Alan Metcalfe,2 John Harney3 and Morris Mott4 have shown how sports history can be used to probe and analyse aspects of class structure, urbanization, modernization, ethnicity and fundamental religious values. From the outset, the exhibit was conceived as a case study of Canadian social and cultural history. Museologically, a cross-over was attempted from a particular interest group and sports aficionados, to serious in-depth interpretation for the public-at-large.

14 The game of curling offers a fascinating example of how distinctive ethnic elements — in this case, "the Scots aim game" — gradually became part of the multicultural fabric of Canada. Curling was first introduced into eastern Canada as an "upper middle class" male social diversion. Since 1900, the west has been at the cutting edge of new developments and has played a major role in popularizing curling across Canada and abroad. Today, curling is claimed to be Canada's most popular amateur sport. Members of both genders, all age groups and most ethnic backgrounds participate widely. Throughout its history, Canada has been noted for its important technological, social and cultural adaptations to winter. Viewed from this perspective, curling offers valuable insights into the unique character and dynamics of Canadian history and culture.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6