Reviews / Comptes rendus

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal The 1920s: Age of the Metropolis

Jean Clair

Helen Adkins, Germany

Jean-Louis Cohen, Architecture and Urbanism

Romy Golan, France, United States

Constance Naubert-Riser, Germany, The Netherlands, U.S.S.R.

Rosalind Repall, Decorative Arts

Christopher Phillips, Photography

Exhibition, Michael Lerch

Catalogue, Jean-Pierre Rosier

20 June to 10 November, 1991

Catalogue, 638 pp., edited by Jean Clair

1 Somewhere in Paris in the early 1920s an unspecified maison "scrapes the sky with its nails/and the skyscraper is only its shadow/in a bathrobe." It is noticed by Dada prophet Tristan Tzara and recorded in De nos oiseaux (1923). Tzara's chimerical view of a city in the 1920s invites us into an era in somewhat the same manner as the enormous and exotic painting Winter, or America by José Maria Sert Y Badia, which dazzles the visitor at the head of the stairs leading into The 1920s: Age of the Metropolis. There we begin a journey into a decade that seems as determined, as it ever was, to elude us.

Display large image of Figure 1

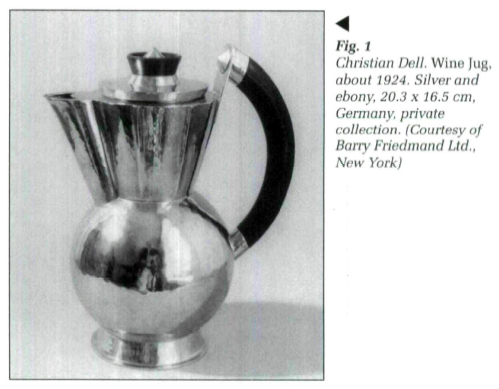

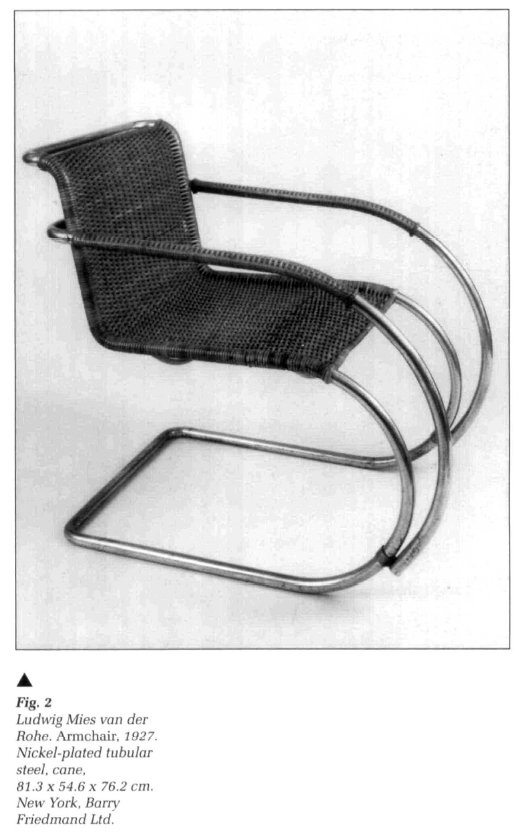

Display large image of Figure 12 Jean Clair, director of the Musée Picasso in Paris, chose the theme "The Metropolis," and chaired the committee of internationally known arts professionals who spent three years assembling the show. Clair wrote the introductory essay to the catalogue, "Red October, Black October," and supervised the selection of the 22 essays composing this very ambitious volume. The exhibition itself presents 729 works by 308 artists and is the largest ever mounted by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA). Designed by Michael Lerch, it makes brilliant use of all the gallery space in the Museum. The labyrinthian layout of large and small galleries greatly enlivens the contents of the show. A music room, complete with player piano performances, provides an appropriate break between the rather severe, if not ominous opening sections and the sorties into cafe life, Art Deco, and the Paris and New York scenes which follow. Because the curators are presenting an era which witnessed the institutionalization of modernism, they are faced with a tension that has plagued curators for many years: How are they to present both the artifacts of fine art and commercial design that were generated during the decade. Indeed, Clair, in his opening essay, points to a development that has important implications for this question: "The most radical innovation of the twenties concerns this concept of reproduction: no longer did the work of art exist exclusively in and for itself ... it had become a prototype ... capable of being reproduced and distributed as often and as widely as desired" (p. 30). This, then, was an important aspect of the modern movement and it begs the question of whether or not the MMFA has succeeded in representing modernism accurately in this show. Has it presented us with the spirit of this age of mass-production? It could be suggested that by their selection of art and artifacts, and the way these are shown, the curators have not entirely acquitted themselves; but a good attempt has been made.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 23 In the exhibition, rooms primarily devoted to fine art, such as painting, are punctuated by displays of craft or commercial art, such as fine tableware or posters. Some objects, such as books, are shown in well-designed glass cases with ribbed bases reminiscent of the neoclassical lines of Art Deco or pedestals graduated in the style of skyscrapers. Artifacts, such as furniture and even a weighing machine, stand out strikingly among canvases, prints and other works mounted on the walls. One entire room is given over to the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes of 1925 and is filled primarily with artifacts. The inclusion of a complete mini-cinema at the end of the exhibition is an interesting touch, allowing the visitor both to rest and to enjoy another very important and innovative facet of the art/design of the era. What is missing, however, in the presentation of the works — and even the most mundane objects, such as a cigarette lighter, are presented as art objects — is a consistent commitment to their social and material history. Throughout the show we are given well-researched captions which set out information about and analysis of the material shown. But they do not always address general questions about the social context of the work or the subjects depicted. Often, we are given just enough to want or expect more.

4 In the exhibition itself, the city, its planning and architecture, are obviously the dominant theme. There are three spaces devoted entirely to it — "The Builders: Berlin," "The Builders: Paris" and "The Builders: New York." These spaces, scattered throughout the show, are augmented by architects' models created by students from the McGill University School of Architecture. Drawings and blueprints are also displayed on the walls and there are several galleries devoted to urban lifestyles. If the city is the constant theme, there are also other motifs which run through the show, such as the machine and speed.

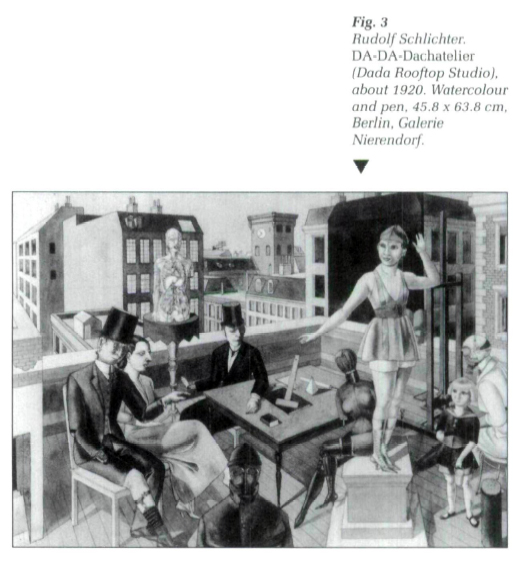

5 We begin with two displays of extremely harsh images of the postwar period ("The Wasted City" and "Berlin... The Aftermath"). The more satiric atmosphere of Dada and Verism follows and the art of George Grosz and Otto Dix figures prominently in these first galleries. Of particular interest here are several editions of Dada magazines displayed among examples of their paintings and collages. A small alcove is devoted to Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau with its eroticism and architectural chaos. This "city" as Schwitters called it, is followed by two large rooms devoted to the Utopian visions of the Suprematists, Constructivists and the Bauhaus. The prominent feature of this section is the reconstruction of Vladimir Tatlin's Model for the Monument to the Third International (1919-1920) which, because of its size and complex design, dominates the room.

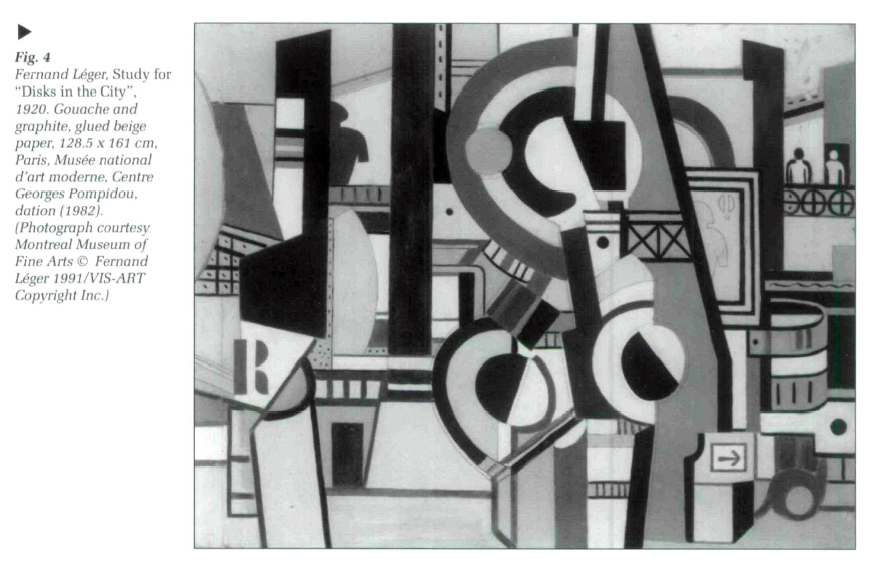

6 As we move towards and past the music room, the exhibit takes on a more popular tone. The curators have attempted to address the implications of Clair's comment about mass-production; namely, what was the impact of the machine on man. The gallery entitled "The Worker" exhibits 20 images and two sculptures showing man and his work-a-day relations with the machine. There is a kind of harmony here. We move from these works to a more strident gallery, "The Mechanical Man." The five paintings here are the work of the socialist Cologne Progressives, one of whom, Franz Wilhelm Stewert, viewed the machine as the workers' slave. Though man and machine are becoming more indistinguishable, the curators do not discuss the implications of this with regard to the human psyche. We soon see the "L'Esprit Nouveau" gallery which exhibits the work of Fernand Léger whose heroic workers are literally mechanical and whose machines are abstractions. Here the curators do tell us that the artists, called Purists, were reaching for a New Man of Order in reaction to the ruined humanity left after the war. Again near the end of the exhibition, in "The New Babel" section on the city in the United States, the captions are quite good. Comments on the working men of the artists Reginald Marsh and Edward Hopper underscore the negative impact of the machine on man's spirit. This depth of analysis should have been maintained throughout the show.

7 It is unfortunate that the curators dodge the issue of the impact of the machine on man in their display documenting Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, the exhibition's namesake. The emphasis here is placed on photographs and architectural drawings of the sets. This gives the impression that Lang, who was a trained architect, was concerned primarily with the city itself in his famous film and not the men and women who lived in it. When one views the film, it is evident that the main questions concern the spiritual nature of man in the machine age — the essential social context of the machine/artifact. Lang postulated that there must be a choice made between head and heart if humanity was to survive. He plunged into man's interior with explicitly Expressionist scenes that represented, for example, Freud's Oedipus complex. In fact, most of the artists in the sections above are making statements about the nature of man in the industrial world. The city itself is of secondary interest.

8 As we might expect, it was the Surrealists who took the boldest leap into man's inner world during this decade. Their work is represented in the galleries entitled "City of Dreams." Here are some two dozen works including paintings by René Magritte and Giorgio De Chirico, as well as portraits of Salvadore Dali and André Breton by Man Ray. Breton's surrealist work Nadja (1928) is on display in a glass case. These galleries and the Expressionistic work in the war-related room at the beginning of the exhibition, are the most probing explorations of man's psyche in the show. Given the importance of this issue in this century, it is surprising that more is not made of the Surrealist contribution to the twenties. The underplaying of the human aspect of the period in favour of asserting the city as the central theme is unfortunate. The subtext of the "self" is never far from the surface though both it and oUier questions of context are better addressed in the catalogue.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 39 The catalogue is a very impressive book and will serve researchers as a useful reference tool for the period. Although some of the essays, such as the piece on George Grosz in America and that on Art Patrons in the 1920s, are slightly thin, the level of scholarship is generally extremely high. The book includes biographies of the artists whose work is in the show and gives a list of exhibited material. The 22 essays can be roughly divided into two categories: those whose focus is the city and those that discuss other aspects of life in the twenties. In the latter category, for example, are two essays dealing with Art Deco. One is a general survey of France. Germany, the United States and Canada, and makes the point that Art Deco and the Bauhaus were moving in somewhat opposite directions. The second essay is a detailed history of the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. Two other essays on advertising of the period highlight the ways in which Expressionism influenced this popular medium in Germany and pinpoint the market as the economic base of Modernism in the United States.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 410 Any reservations about the book that arise come from the problem that is evident in the exhibition itself; namely, the choice of the city as the dominant theme and the emphasis on architecture. Even in the catalogue essays covering aspects of urbanization, notions such as the "soul" and "spirit" are recurring motifs. For example, in Cologne, the architect Fritz Schumacher sought "to rescue the soul of modern humanity" (p. 331). In Berlin, the 1920 Dada fair lamented that "the spirit is brutality" (p. 263). In Paris, the Surrealists went so far as to view the city itself as a metaphor for Freud's unconscious (p. 361). The detailed histories of architecture and urban planning projects in the Old and New Worlds are, of course, important, but it is unfortunate that no single essay addresses the spiritual questions that most artists of the era seem to have been unable to avoid.

11 However, some of the important social context of the art and artifacts of the decade that is missing in the show itself is developed in the catalogue. The essay on "The Shop Window" by Jean-Paul Bouillon does document the role of commercial art in everyday life. And the piece "Decorative Arts from the Twenties" by Rosalind Pepall discusses materials, technology and philosophy behind the artifacts produced by this movement. There is, on the whole, here, an effort to give the social history of the design of the era. The implication is that perhaps different sorts of artifacts and art should have been included in the show itself. Examples of commercial art other than posters, more views of factories and workshops and more everyday objects, such as the typewriter and the lathe pictured in the "Manhattan Transfer" section, would have been in keeping with the stated intention of the show to document Modernism.

12 One of the most significant problems with the show is rooted in Jean Clair's assumption that the twenties represent a break with the past. This model of discontinuity is misleading. To some extent, the decade is trying to reclaim some of the creative and spiritual ground lost by the dehumanizing economic and social processes of almost 200 years of industrialization. There are two large machines in the show: the de Havilland D.H. 60X Moth airplane and the Bugatte Royale Type 41 motor car. They are completely arresting to view but they bodi suggest a relationship between machine and man which was not typical of the era. These are the machines of the elite. However, both they and other, more proletarian, machines had one thing in common, and that was speed. Like Marinetti's Futurist Blue Train packed with savage animals and racing towards oncoming disaster, the car and the airplane are at once threatening, seductive, primitive and new. Even if the Futurist obsession was somewhat modified by the twenties, it is still there. The decade is speeding towards something. The question is, in which direction is it going — towards the future or the past? Or, to take another perspective, is it speeding towards or away from the self? The appearance of speeding from the present, of thumbing the nose at the bourgeoisie, by the Dadaists for example, was an attempt to reclaim customs and perspectives that existed before the rise of the nineteenth-century industrial middle class. Much of the decade was speeding backwards and into humanity's interior. The "Taylorizing" theorists that waylaid some of the most creative minds of the decade certainly pointed to the fact that, in the United States, at least, some artists were speeding away from the marketplace. Reclamation, then, was at the root of the seeming rejection of the past.

13 It is not surprising that even an exhibition as ambitious as this one was not completely successful in achieving what it set out to do, namely to capture the "Spirit of the Age" of one decade, the twenties. Museum curators have, for many years, and particularly in the 1980s, been engaged in discussions about practical approaches and theoretical underpinnings of museum collection and interpretation. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts has taken on the decade in which many of the points of debate first surfaced. There seems, as yet, to be no really solid consensus about how to treat the history of design and popular culture in the museum setting. Modernism itself presents a particular problem. Thus, the MMFA cannot be faulted if they did not entirely achieve their goal. At this point, it still seems that the works themselves speak most eloquently.

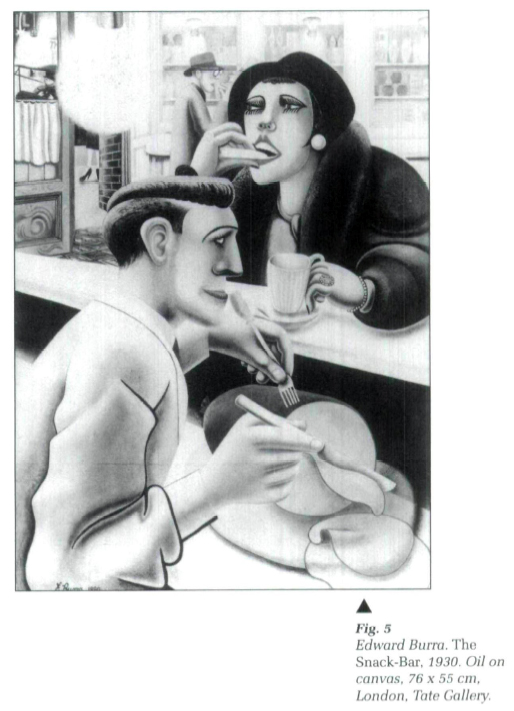

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 514 As if stepping out of one of the nightmarish images in the shadowy Berlin room that urges us into the first galleries of the show, Marlene Dietrich seduces us with a song about one of the regular features of the postwar world — the black market:

like wedding rings?

sh-h-h. Tiptoe.

Trade your things.

This mood is perfectly captured by much of the Curatorial Statement exhibition. Not surprisingly, like the twenties themselves, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts' show delivers quite a bit more than anyone bargained for.

Curatorial Statement

Editor's Note: For a curatorial statement, it is recommended that readers consult the lead essay of the exhibit catalogue. Entitled "Red October/Black October," the essay was written by Jean Clair, Director of the Musée Picasso (Paris) and curatorial director of the exhibition.