Reviews / Comptes rendus

Impact of the Bauhaus:

Ceramics of the Weimar Republic, 1919-1933

Curator: Meredith Chilton

Designers: Ivy Lee and Steven Petrie

Duration: 11 September 1990 to 6 January 1991

Publications: Illustrated poster; no catalogue

1 A map of the revolutionary flashpoints in Germany in November of 1918 is an image dotted with pastel circles that corresponds to the pattern of violence that swept William II from power and provoked the proclamation of a republic. This revolutionary design for the future gave way to a new government in February 1919 and the city of Weimar became its capital. The Weimar Republic endured until 1933 when the Nazis came to power. Subsequently, many of the ceramics factories that produced the work displayed in Impact of the Bauhaus: Ceramics of the Weimar Republic, 1919-1933, were closed.

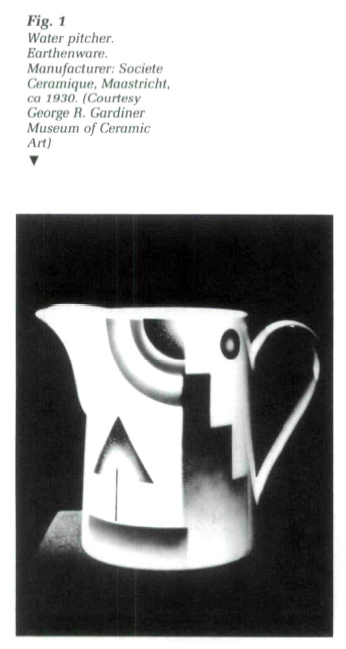

Display large image of Figure 1

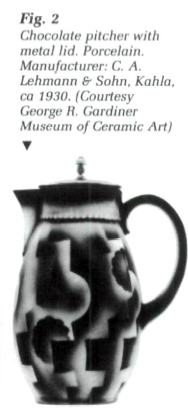

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 22 The Bauhaus school's ideas were rooted in artistic movements that looked to the past as well as the future. As new forms of art from impressionism to cubism were changing tastes in the German Empire, Hermann Muthesius, strongly influenced by the British Arts and Crafts Movement, founded the Werkbund in 1907. Its aim was the reconciliation of art, craft, industry and trade. In 1912, Walter Gropius joined the Werkbund and its ideas, with varying emphasis, informed the plans he made for his school, the Bauhaus, which opened in 1919.

3 The tumult of futurism, constructivism, and dada, which were part of the Weimar and Bauhaus scene, arrived in Canada in 1927 when the International Exhibition of Modern Art came to the Art Gallery of Toronto. Gropius' school was well represented. Works by Wassily Kandinsky, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Paul Klee, all teachers at the Bauhaus, were part of the exhibition. Johannes Itten, first teacher of the Vorkurs, the compulsory introductory course, also showed work. Over 100 artists from 20 countries were represented. Lawren Harris, who recommended that the show be brought to Canada, commented that "the works impressed one as exemplifying sincere adventure, research and expression" and "there is nothing in it of an offensive nature, that is, decadent in the moral sense." The reviews of the exhibition were mixed and tended towards the negative. The Mail reporter wrote that "people who have worked themselves into paroxysms of rage over the experiments of Canadian modernists...will leave the International Exhibition of Modern Art...with the feeling that our Group of Seven is devoting itself to ultra-realism."

4 Yet, Canadian artists were influenced by the trends introduced by the exhibition. Gordon Webber studied with Maholy-Nagy for three years at the end of the 1930s and Bertram Brooker, an expatriate Englishman, was strongly influenced by Kandinsky in the 1920s. Modernism was, of course, flourishing in Weimar Germany. The purpose of the Gardiner Museum's exhibition is to illustrate the way in which the Bauhaus school's ideas were put into production by ceramics factories in that country until they were censored by Hitler.

5 The exhibition Impact of the Bauhaus has had a long period of gestation. It began in 1978 at a fleamarket in Berlin where Tilmann Buddensieg bought the first piece of his collection of Weimar ceramics which eventually numbered 450 items. The collector was struck by the bold construction of shape and the patterns that, he believed, reflected the influence of the Bauhaus.

6 This exhibition is a very beautiful one, well designed, with appropriate use of a strong central diagonal line, by Ivy Lee and Steven Petrie. The neutral colours that surround the well-lit cases allow for maximum impact of the striking palette of browns, blues, mauves, greens and reds which enliven the artifacts themselves. The thirteen cases are distributed between an entrance way and a central viewing area. About a dozen factories are represented and over 50 pieces are displayed, dating mainly from the late 1920s and early 1930s. The composition of the pieces is given in captions: earthenware, stoneware, cream ware and porcelain. Extended captions with historical information are presented on two well-placed posts. These larger captions outline the goals, mass-production and marketing techniques used by the factories whose work is displayed and emphasize their efforts to provide cheap, beautiful wares to the common consumer. However, the most interesting puzzle about the Weimar ceramics is not addressed.

7 The Bauhaus pottery workshop began at the Schmidt stove factory in 1919 under the direction of Gerhard Marcks. Marcks first became friends with Walter Gropius when he designed a ceramic wall for a restaurant installation by the Werkbund at the Cologne Exhibition of 1914. Marcks' leading principle when he joined the Bauhaus staff in 1919 was that of "uniting handicrafts with art as much as possible." In 1920 the workshop was moved to a pottery owned by Max Krehan in Dornburg, 25 kilometres from the school at Weimar. Krehan's operation produced traditional work typical of the region and Marcks' ideas flourished there to the point of being "reactionary" during the first years. The emphasis on the marriage of art and technology was more truly part of Gropius' notions for the second Bauhaus school established at Dessau in 1925 where there was no pottery workshop. Marcks was not alone in not bowing to the needs of advancing technology. Even the cubist design teacher Lyonel Feininger avowed that this approach was "exactly what we didn't want."

8 The tensions between old folk forms: "squat, potbellied shapes and the rude, strongly protrusive...spouts and handles" and the newer work of such apprentices as Otto Lindig and Theo Bogler was resolved in 1923. The shop changed definitely to "mass-production models." Primitivist designs slid into geometric ornamentation. The squat folk form was transformed into bulky shapes with centralized weight and appendages such as spouts, handles and lids attached as separate, sometimes geometrical forms. Otto Lindig worked for simplicity of shape for manufacture and after 1923 aimed for a coalition of hand work and mass production. Finally, earthenware methods were changed to give more freedom of expression to the artist.

9 This tension between old and new is the central puzzle of the Impact of the Bauhaus exhibition. Because there is no published catalogue, the viewer is left with some confusion. It was intended that this deficiency would be made up by the discussion of ceramic art in the symposium that accompanied the show. The Gardiner Museum has also provided a teaching guide by Helen Stone for use by school tours. However, the general viewer is not given enough information to assess the complex connections between the Bauhaus and the ceramics factories. Perhaps photographs of actual Bauhaus pottery or some other type of documentation could have been included in the exhibition to address this problem.

10 In his essay for the catalogue that accompanied the display of these ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1986, the collector, Buddensieg, noted the influence of mechanization on Bauhaus production. Yet, as we have seen, this idea was not unchallenged at the Weimar school. Still, it so clearly informs all the ceramics in this collection that one must wonder about the exact connection between the Bauhaus and the factories. What happened to the Bauhaus potters after the school workshop closed in 1925?

11 The careers of some of them can be traced. Otto Lindig remained after the Bauhaus school left and became director of the Keramische Werkstatt at Dornsburg. Theo Bogler worked briefly in the Velten-Vordamm factory along with many other Bauhaus students in the late 1920s. Other students worked at the Majolika-Manufaktur, and the Karlsruhe and Staatliche Porzellan-Manufaktur. These factories do not show work in the Gardiner exhibition.

12 It is also evident that there were other ceramics schools in Germany; one, for example, at Bunzlau where there were several ceramics factories, three of which are represented in this exhibition. Who were the other designers and where did they train? Only one factory designer, Herman Gretch of the Villeroy and Boch factory, Dresden, is identified in the captions. Bundensieg has noted in one of his essays that documents such as factory catalogues and trade gazettes are no longer extant. Perhaps the Bauhaus Archiv in Berlin had some of the answers.

Display large image of Figure 3

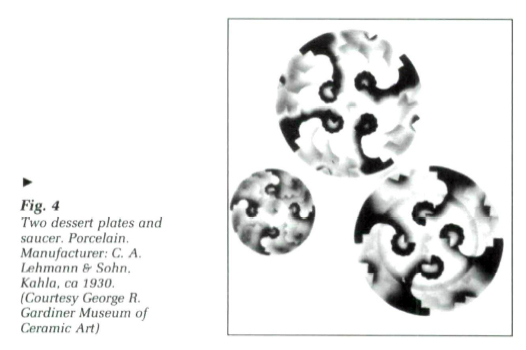

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 413 In Canada, as we might expect, having seen the reaction to the arrival of Bauhaus art here in 1927, "modern ceramics" arrived late and were not readily accepted. Trade catalogues, such as those from Birks and Nerlich and Co., suggest a complete absence of modern design in this aspect of Canadian life in the 1920s and 1930s. Ceramics designed by Russel Wright were introduced here late in 1939 and were advertised through the 1940s. Two lines, commonly known as Carnivalware and Fiestaware, featured bulky round forms and geometric features such as handles. These were reminiscent of the Weimar designs.

14 The Canadian reaction was predictable. A writer in The China, Glass and Gift Buyer, a trade journal, wrote that, "to the casual observer, the objective of the artist often seems to be to make the article look as unlike as possible what it is supposed to be. Apparently, if he achieves this effect, it is a good functional design." This Canadian comment may be the most amusing footnote to an aspect of material history which is as paradoxical as the social history which gave rise to it.

15 The exhibition Impact of the Bauhaus leaves the viewer with many unanswered questions. Yet, by simply seeing the beautiful Weimar ceramics, the influence of the Bauhaus becomes evident. Patterns based on the designs of Kandinsky or closely resembling the structures and colours of Feininger are visible everywhere. The swirls and stripes of potters Johannes Driesch and Theo Bogler are also here. We see the bulky forms and functional, sometimes geometric, handles and spouts that were part of the Dornburg pottery designs. A flat-topped teapot resembles the work of Bogler at the school. The graduated colouration of spray paint work on many of the jugs and pots is filled with references to cubism and futurism.

16 In the final analysis, the exhibition, in fine post modern fashion, leaves visitors to piece together the whole story for themselves.

Curatorial Statement

Despite Material History Review's policy of arranging for statements from curators responsible for exhibitions reviewed in it, circumstances did not allow for such a report in connection with the Impact of the Bauhaus: Ceramics of the Weimar Republic, 1919-1933 exhibition. Instead we are able to provide background information based upon documentation kindly supplied by the Smithsonian Institution Travelling Exhibition Service (SITES). Readers interested in more details may contact the Project Director of SITES at 1100 Jefferson Drive, SW, Washington D.C., 20560, U.S.A.

17 In the climate of artistic ferment that flourished in the years between the two World Wars, modern ceramics came of age in Germany. For the first time, well-made and attractive ware became available and affordable for the majority of German citizens. From the smallest domestic utensil to the architecture of its cities, Germany was determined to rebuild itself physically and spiritually in the wake of World War I and the 1918 revolution. With a new constitution and a new name, the Weimar Republic set out to erect a new—and many hoped classless—society, in the process providing everyone with the most advanced housing, schools, places of work, and products for daily living.

18 From this ferment, a new breed of designers emerged to champion "industrial art." The new design doctrine demanded an exhaustive study of materials—many recently formulated—and manufacturing processes. The results were revolutionary. Ceramics and other household objects, designed strictly for function, celebrated their machine origins rather than mimicking the florid ornament of their handmade ancestors. The younger generation of artists and designers, sobered by the carnage at the front, had come home from the World War I trenches eager to focus the new technical advances and media on bettering humanity. The liberal Weimar government encouraged their efforts. As Germany resumed its peacetime quest for industrial power, artists and reformers alike sought to combat the numbing effects of rapid mechanization on the people.

19 The Bauhaus, born in the city of Weimar in 1919, was the most famous, but not the only, school in Germany that trained architects and designers for work in industry. Teachers and students worked directly with industry to produce designs for manufacture. In this new mood of cooperative effort, the decoration of ceramics evolved into a collaborative process involving maker, merchandiser and consumer. Thus the stage was set for a decade that revolutionized production. Producers came to use a few simple forms for many lines of vessels: coffee, milk, tea, water—even cups and sugar bowls—were distinguished only by size. Decoration underwent dramatic changes. Applied or relief ornament vanished; moulded ribbing replaced incised decoration and other handwork. Marketing and production, in the new cooperative spirit, worked hand in hand. Pieces were sold not in sets, but individually, inviting consumers to combine patterns creatively, all of which were designed to complement one another.

20 In the early 1930s, with Hitler's rise to power, the modern aesthetic fell from grace as rapidly as it had risen. The idea of art as a progressive force was anathema to the Nazis; "communist" ceramics—visible symbols of the Weimar regime—were to be smashed. Shapes and decoration revealing the mass-production process were discouraged (although improved production techniques remained); factories were forced to imitate the thrown forms and hand-painted decoration of traditional German folk art.

21 By responding to postwar Germany's urgent needs, Weimar artists, architects, and designers had hoped to reshape society by gaining control of an increasingly mechanized world. Although their movement was destroyed by the Nazis, in decades to come their rhetoric—drained of its radical politics—would find a fertile home in America. That was to be a gradual process, though, unmarked by the urgency of the Weimar era.

22 All works in the exhibition are from the German National Museum, Nuremburg, Germany. They were collected and documented by Dr. Tilmann Buddensieg, Professor, Kunsthistorisches Institute, University of Bonn, who donated his collection to the museum.

23 In an essay written to accompany the exhibition shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1986, Professor Buddensieg noted,

24 This exhibition was developed for circulation by the Smithsonian Institution Travelling Exhibition Service. The project was made possible in part by a donation from the Phillips Petroleum Foundation.

Material quoted about the International Exhibition of Modern Art is courtesy of the Archives of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.