Reviews / Comptes rendus

Garth Clark, Robert Ellison and Eugene Hecht, The Mad Potter of Biloxi: The Art and Life of George E. Ohr; American Craft Museum, George Ohr: Modern Potter (1857-1918); Canadian Museum of Civilisation, The Turning Point: The Deichmann Pottery (1935-1963)

Curator: Dr. Stephen Inglis

Duration: 17 January 1991 to 1 March 1992

1 The publication of The Mad Potter of Biloxi: the Art and Life of George E. Ohr by Abbeville Press and the exhibition "George Ohr: Modern Potter (1857-1918)" curated by Dr. Martin Eidelberg of Rutgers University for the American Craft Museum, New York, are coincidental in time and theme but otherwise distinct events. Together they reflect a current interest in George Ohr, whose important contribution to the history of American art pottery remained obscure until 1972, when over 7 000 pieces of his mature work that had been packed away in crates were purchased by an antiques dealer from his family in Mississippi.

2 It was in 1972 that the first serious study of American art pottery in the context of the Arts and Crafts Movement was undertaken by Dr. Eidelberg in an exhibition organized by Princeton University, "The Arts and Crafts Movement in America 1876-1916." In the catalogue, Dr. Eidelberg wrote that this was an experimental period for art pottery tending toward oriental influences and inspired by the ideals of craftsmanship advocated by William Morris. The earlier work of Ohr included in the 1972 exhibition would appear to fit this description, though Dr. Eidelberg pointed out the history of the Biloxi potter was still somewhat unclear.

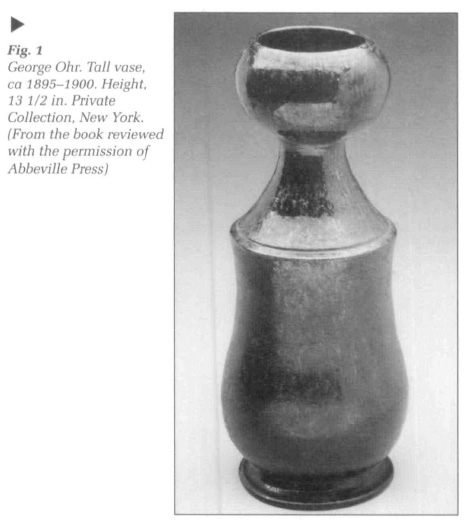

Display large image of Figure 1

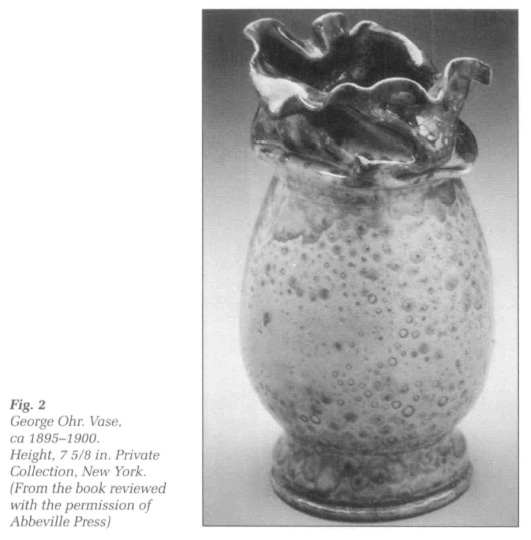

Display large image of Figure 13 Unfortunately, with no catalogue to accompany the current exhibition, Dr. Eidelberg was not provided with the opportunity to reflect on almost 20 years of study and awareness of Ohr's work. What makes Ohr fascinating for us now. and this can be attributed to the availability of his more mature work, is that he made beautiful pottery while breaking the number one rule of good craftsmanship. Few of the pots, especially of the later work, could be said to be entirely useful. Spun to thicknesses of only a few millimetres, the pots were then folded into themselves, twisted, crimped or collapsed until they were barely recognizable as functional shapes. Ohr's glazes are colourful, unpredictable, often combined in unlikely experimental patterns on a single pot. His trademark "lava glaze" is a thin red glaze, that has bubbled, burst and hardened into crusty glass accretions on the surface. It is at once visually stimulating, yet deterring to the touch.

Display large image of Figure 2

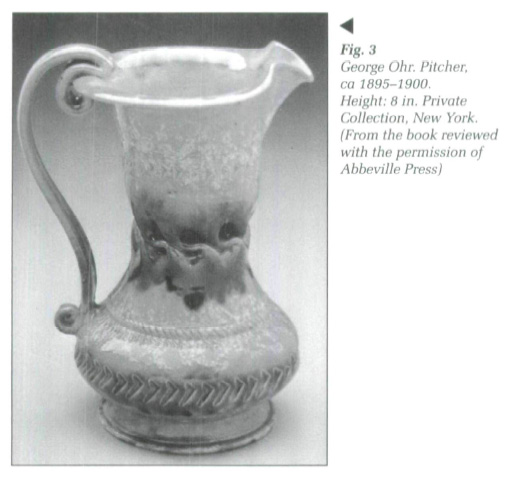

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 34 The Abbeville publication, of a very high production standard and finely illustrated with colour plates, serves as a good introduction to Ohr's life and work in the essays by Eugene Hecht, Robert A. Ellison, Jr. and Garth Clark. References to dating and chronology are scattered through all three essays. This kind of overlay, while allowing for different interpretations of the facts, is no substitute for a catalogue raisonné where one expects a more complete and focused assessment of how Ohr's life and work affected his stylistic development. The exhibition attempts this kind of connoisseurship of Ohr's work by period, starting off with the earlier utilitarian and novelty items and ending with unglazed bisque ware, all arranged in cases dwarfed under the tall ceilings of the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York, a centre for ceramic studies designed by I. M. Pei. Many of the more intriguing pieces from the book are missing from the 82 exhibited works dating from 1882 to 1907. The exhibition had originally been conceived to contain 190 pieces, but this had to be reduced due to prohibitive insurance costs.

5 Each of the essays in the book take on a different theme with Eugene Hecht concentrating on Ohr's biography, Ellison on the sources and context of Ohr's style and Clark the more difficult issues of artistic expression and Ohr's use of language, which he claims in its abruptness, disruption, and play with conventions anticipates the manifestos and poetry of the European dada and futurist movements. Yet Ohr would appear to have fostered no movement and it is clear from the handbills referred to that it was not his intent to propose a radical vision of the world, beyond the promotion of his own work as part of it. As all authors point out Ohr was a proud loner, albeit one of obvious humour and good will, with few steady patrons and little to document his work other than what he embellished for the contemporary, of which the authors provide plenty of examples. One of the primary references for each of the three essays is the autobiographical article of 1901 in Crockery and Glass Journal, "Some Facts in the History of a Unique Personality," illustrated with a photograph of Ohr grinning behind his 18-inch waxed moustache.

6 In Hecht's essay we find that Ohr was the son of a blacksmith who began his potter's apprenticeship in 1879 with a New Orleans potter of utilitarian ware. By 1884 Ohr was to claim for the benefit of souvenir hunters that no two pieces he made were alike, although in reality Ohr produced a substantial quantity of utilitarian ware to support his family. During the early 1890s, Ohr began to manipulate his forms as well as to expand to colour range of his glazes. Much of this work was destroyed in a fire of 1894. The rationale for the dating of pottery illustrates in the book is not explained but seems to be broken into periods, ca 1888-94, ca 1895-1900, ca 1898-1910, based on the style of signature Ohr used during these years.

7 Ellison's essay, '"No Two Alike:' The Triumph of Individuality," is the most satisfying in its discussion of contemporary sources that raise questions as to whether Ohr's work belongs strictly within the context of the Arts and Crafts Movement. His role model was no William Morris, but Bernard Palissy (1510-90) the French sixteenth-century ceramicist whose eccentric table settings and decorations for the Royal Court had been published in the 1850s. Contemporary comparisons made by Ellison include the line of folded, bent and indented pots designed by Christopher Dresser for Linthorpe Pottery of Middlesborough, England ca 1879-82, which in the English context is less like art than novelty or whimsy. In France a more serious approach to adventurous, high-fired colours was undertaken by Ernest Chaplet and Auguste Delaherche. Ellison presents some convincing comparative illustrations of the work of Delaherche, as well as tenth-century Chinese examples and Greek red-figured vases to show that Ohr had studied his field carefully. While Ellison points out on page 76 that Chaplet and Delaherche exhibited pieces at the Chicago Worlds' Columbian Exhibition of 1893, he neglects to mention what Hecht discussed many pages before, that George Ohr was there also. Obviously Ohr recognized the "novelty" trend in ceramics as a legitimate pursuit for a serious potter and he didn't hesitate to explore its expressive limits with the help of traditional sources.

8 Ohr's best work both confirms and challenges the principles of the Arts and Crafts Movement that had been developing since the mid-nineteenth century. An enthusiasm for art pottery, produced primarily for aesthetic or decorative purposes, grew in the 1870s with exposure to imported Japanese ceramics and intolerance with unappealing industrially-produced decorative art. To resolve this problem John Ruskin and William Morris had advocated that there should be no distinction between the artist and artisan or technician, that no decorative art could be of good quality unless there was joy in the making, that there should be a more honest approach to form and ornamentation and experimentation and exploration of the full possibilities of materials. In order to achieve a decorative art with greater aesthetic value, followers of the Arts and Crafts Movement turned to nature for inspiration. Art potters who adhered to the movement most often interpreted nature as strong, perfect and fertile in sensuous organic forms integrated into the decorative scheme of the vessel. Ohr, however, in his mature work presents us with a contrary vision of the natural world as aberrant, wilted, uncontrolled, while his glazes preserve the failures and mistakes of nature.

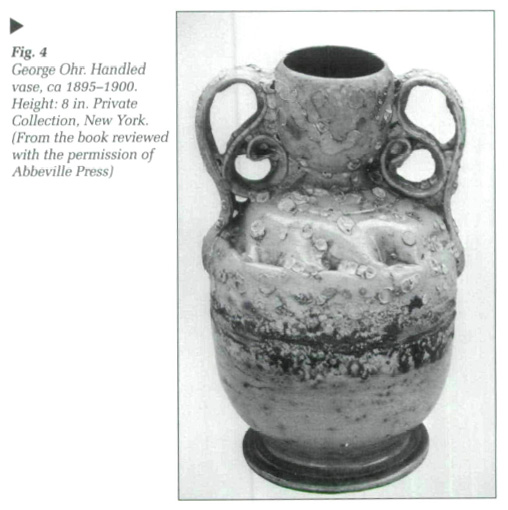

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 49 George Ohr's claim that no two of his pieces were alike was not simply a promotional slogan to sell souvenirs of Biloxi; it also served as a parody of what the Arts and Crafts ethic had become by the end of the nineteenth century in the wake of the movement's popular commercial success. To meet the demand for their work, American art potteries such as Rookwood, Greuby and Van Briggle hired staff to apply prescribed glazing and decorative painting to pots mass-produced from moulds, forcing art potteries to embrace the very production techniques for which they had been founded to provide an alternative. The attractively decorated, functional shapes developed by art potters would eventually be adopted by industry in the "Machine Art" era of the 1920s and 1930s. At a time when this transition was underway, Ohr perceived his "babies," as he called them, as art works that could never be duplicated by a machine. As he maintained full control of his pottery from concept to firing, Ohr should more properly be seen as a forerunner of the studio-potter.

10 It is unlikely that William Morris, who died in 1896 just as Ohr entered his mature period, would have approved of the Biloxi Potter's style. Both men's careers were committed to preserving the artist's role in making and proposing an alternative to machine production, but Morris was bound by the craftsperson's ethic of fitness for purpose and a romantic obsession with the past. Ohr's obsession was with what Garth Clark terms the "theomorphic role" of the potter; the act of creation that led Ohr to reveal a degree of individual presence in the manipulated forms and experimental glazes that would have been alien to Morris. Ohr's fortunes, however, were very much tied to the Arts and Crafts Movement. His retirement from the art pottery business in 1915 was a result not so much of neglect of his work as it was of a general decline in interest in the hand-made object as industrial production came to supply the variety and quality of art pottery at considerably lower prices.

11 The exhibition, "The Turning Point: The Deichmann Pottery 1935-1963," at the Canadian Museum of Civilization from 17 January 1991 to 1 March 1992, provides a unique opportunity to contrast the art pottery practice of George Ohr with the next generation of studio potters represented by the ceramic work of Kjeld and Erika Deichmann. The exhibition highlights a major acquisition from Erika Deichmann-Gregg of work surveying the couple's early struggle with local clays to the successful production of domestic and decorative ware. The ceramic pieces are supported in the exhibit by sketch books, photographs, a visitor's register and notebooks containing glazing recipes. National Film Board documentaries from the 1950s are a rich source of information about the Deichmanns' working methods, though their continuous play in the exhibition space tends to be distracting.

12 Kjeld studied philosophy before travelling to Paris, Munich and Florence to study painting and sculpture. Attracted no doubt by Canada's aggressive immigration campaigns, he first settled in Saskatchewan where he met Erika, who was visiting with her parents. In 1932 the couple moved to the Kingston Peninsula in New Brunswick where Kjeld first discovered his interest in clay. After apprenticing with a Danish potter in 1934 they returned to the Kingston Peninsula and built a studio. His training as an artist and its application in the development of the pottery is made evident in the exhibition with the inclusion of charcoal and pastel studies on paper. One sheet is covered in quick sketches of shapes for vases, bowls and plates, another sheet contains working drawings for the "After Dinner Set" commissioned in 1951 by the City of Saint John for Queen Elizabeth II. In this drawing the coffee pot and cups are drawn precisely, and accompanied by notes as to weight, dimensions and scale. It is doubtful if Ohr, on the other hand, ever picked up a pencil to develop his ideas, as the result seems so much like the outcome of chance and impulse at the wheel.

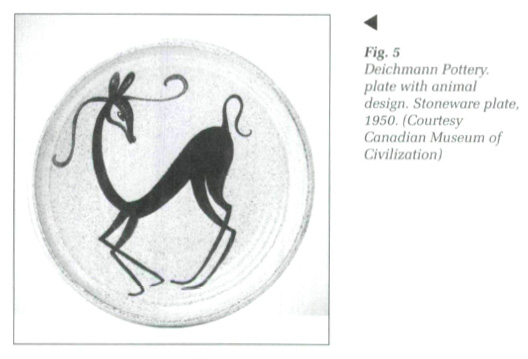

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 513 The Deichmanns are recognized today as Canada's first studio potters and the forerunners of the craft revival of the 1960s. While the Deichmanns chose an isolated location for their studio on the Kingston Peninsula after their arrival in Canada in 1934, they maintained close contact with Maritime artists, as well as colleagues in the Canadian Guild of Crafts, founded in 1936. Family photographs in the exhibition show the couple with artists Louis Muhlstock and Millar Brittain. Portraits of Erika by Brittain and Jack Humphrey from the late 1930s reveal a fascination with her striking Scandinavian features. An oil on panel of the potters' studio, ca 1940, by Peggi Nichol Macleod depicts the couple hard at work watched by their three young children. It was under the auspices of the Canadian Guild of Crafts that the Deichmanns' exhibition career was launched at the Paris World's Fair in 1937. Evidence that the Deichmanns were instrumental in establishing professional credentials for the studio potter is provided in the exhibition with the inclusion of a number of magazine features including the widely read Canadian Geographic Journal.

14 The 70 pieces included in the Canadian Museum of Civilization exhibition are displayed in large glass cases with unobtrusive white metal frames. They sit on raised platforms of a light wood with a muted grain finish that works well with the range of glaze colours. The exhibition catalogue was, unfortunately, delayed in production, although it will be available for review in the next issue of Material History Review. The catalogue should be of great use in documenting the Deichmanns' style, which develops discernably from case to case through the exhibition. An informative commentary on techniques and glaze mixes by Erika Deichmann-Gregg however, accompanies the labels of each piece. The case containing the earliest work from the mid-1930s show the Deichmanns working with simple forms in dark glazes inspired by traditional Danish pottery and fired in a wood-burning furnace. Examples from the 1940s show a broadened range of sources evident in the yellow glazed "Kish" bowl of 1942, inspired by archaeological excavations of the ancient city in southern Iraq, and the "Porringer" bowl of the same year, recalling a popular form for early soup or porridge bowls. By the 1950s the forms of Deichmann pottery had become more ambitious and freely interpreted. An example is the 1955 double-flared stoneware bowl, glazed in copper carbonate with a light surface colour of alkaline blue.

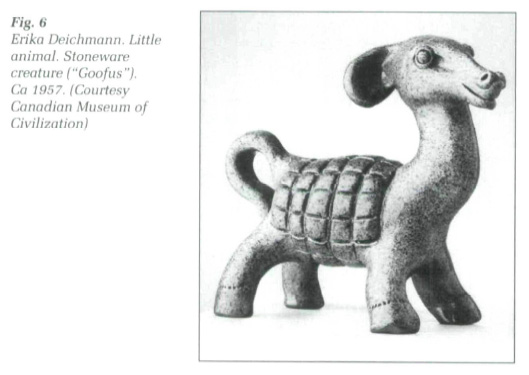

Display large image of Figure 6

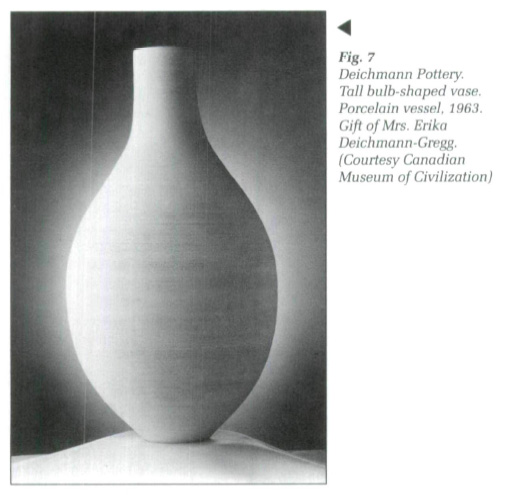

Display large image of Figure 615 The cases surveying the period 1955 until Kjeld's death in 1963 represent the real maturity of the Deichmann pottery. An exceptional range of technique and glazings, including beautiful thrown porcelain pieces and the use of magnesium carbonate pebble glazes reflect the Deichmanns' continuing interest in ceramics as a venue for the application of aesthetic principles. A statement made on the occasion of a 1961 exhibition at University of New Brunswick reflects the Deichmanns' desire to have their pottery viewed within the context of current artistic practice: "Our approach to our work is an attempt to capture and express the abstract in line, colour, texture and shape." As craftspeople the Deichmanns' work remained tied to tradition of Far Eastern ceramics and the example of such studio potters as Bernard Leach, who had studied with the Japanese. A porcelain bowl from 1959 to 1962, Erika relates, was gas-fired (in an alternating atmosphere), "with a widely flanged edge - what the Chinese call the 'white lip.' " In addition to the lighter forms of Far Eastern ceramics, the influence of the freer shapes popularized in commercial ceramics by such designers as Russell Wright and Eva Zeisel, are also suggested in this period. A lamp base shows that the Deichmanns could adapt traditional pottery techniques to new and innovative forms required for the modern household. It is clear that the functional role of the large scale pieces contained in the final case in the exhibit is secondary to the Deichmanns' interest in decorative form, colour and surface texture. The tall bulb-shaped porcelain vase of 1963, for example, would be reminiscent of the 1930s work inspired by traditional Danish forms, were it not about a half metre high and left in the unglazed bisque state. One can only guess what a few more years of Deichmann production would have yielded.

16 The narrator of the National Film Board documentary included in the exhibition broadcasts loud and clear that the Deichmanns were "working together as families did ages ago," implying they were not only reviving a craft, but a way of life that was contrary to the urban, industrial boom of the 1950s, just as George Ohr in his time was proud that no machine would ever duplicate his work. One of the last panels in "The Turning Point" contains a quote by Kjeld Deichmann that expresses sentiments close to George Ohr's claim of no two alike: "The real craftsman is essentially an experimenter who dislikes repeating himself. He is happiest when he is creating fresh designs and finding new ways of expressing old truths." It is clear from the publication and exhibition reviewed that Ohr was indebted to traditional practice, but there was also a provocative side of his work that explored the structural and functional limits of the medium, limits that the Deichmanns would appear to have adhered to faithfully. While Ohr's example of independence and insistence on the integrity of his craft as an avenue for personal expression reflect the influence of William Morris and look forward to the generation of studio potters that included the Deichmanns, he did not share with them the craftsperson's love of detail, but was rather more interested in the expressive gesture. This lead to a body of work that sometimes obscures the delineations between pottery and sculpture and places Ohr's example closer to the work that dealt with problems of formalism during the craft revival of the 1960s.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7Curitorial Statement:

The Turning Point: The Deichmann Pottery (1935-1963)

Stephen Inglis

17 In January, 1991, "The Turning Point: The Deichmann Pottery (1935-1963)," an exhibition on Canada's first studio potters, opened at the Canadian Museum of Civilization. In March 1992 it will begin travelling to six other locations across Canada. This statement outlines the background to the exhibit project, the collection on which it is based and the curatorial objectives.

18 In the Spring of 1987, Erica Deichmann-Gregg of Fredericton, New Brunswick, came to Ottawa to receive the Order of Canada in recognition of her pioneering contribution to the crafts in Canada. During her stay, we met and she agreed to facilitate an acquisition by the CMC of ceramics spanning her career and that of her late husband, Kjeld Deichmann. In November 1989, I travelled to Fredericton and selected 64 pieces from Mrs. Deichmann-Gregg's personal collection, which were acquired by the CMC through donation and purchase. I returned to New Brunswick again in the summer of 1990. It is this collection with its accompanying documentation that was on exhibit in the Fine Crafts Gallery of CMC's Arts and Traditions Hall, and presented in the catalogue released in June 1991.

19 The collection is significant because it documents the Deichmanns' entire career from first firing to last and because it is fully described by the artist. Some of these pieces were retained for the 55 years since the Deichmanns' first firing and all were preserved for the 27 years since their production ceased. Although other examples of Deichmann ceramics exist, in public collections in New Brunswick and Ontario and in private hands, this is probably the most important single group of work.

20 The Deichmanns are widely acknowledged to be the first studio potters in Canada; that is, the first to set up a studio, kiln and other facilities, which enabled them to produce a personalized series of domestic and decorative art pottery as a means of making a living. In this sense, they are the precursors of virtually all the contemporary ceramists represented in our fine crafts collection. The collection and exhibit in this way provide an historical perspective on our collection, on those of other institutions and on those of visitors who own or collect Canadian ceramics.

21 The exhibition project had four main objectives. The first was to document the development and scope of the Deichmanns' ceramic production. The thematic focus here was the development of the career of Erica and Kjeld Deichmann as exemplified by their work, from rough ware made with local clays and fired with wood in the 1930s to the more sophisticated forms, surfaces, colours and techniques which characterized their final work in the early 1960s. Emphasis was placed upon the vast range in quality, style and function of work during their career, their constant experimentation with clay composition and glaze types (over 3 500 glaze tests), and the division of labour by which Kjeld did the throwing and Erica the painting and glazing.

22 This thematic focus was developed by arranging the collection chronologically, highlighting the earliest, latest and best-known pieces. In addition, the technical developments and innovations are described in the artist's own words (from Erica's taped descriptions). The working processes are presented through excerpts from taped interviews and historical photographs of Erica and Kjeld working in their studio. Film footage of the Deichmanns at work augments the photographs.

23 A second objective was to examine aspects of the history of the studio crafts movement in Canada. The thematic focus here was the pioneering role of the Deichmanns in the studio crafts in Canada and on their work within the wider context of the crafts movement. Their innovative ceramic work is emphasized as is their search for markets and contacts. We have used interview transcriptions which describe these searches.

24 The Deichmanns were instrumental in gaining support for craftspeople. Excerpts from their brief to the 1951 Massey Commission on the Arts are included. Historical photos of the pioneering demonstrations and workshops in Montreal and New York, for example are displayed as are early magazine articles and film footage on their work and contribution to Canadian art and tourism in New Brunswick.

25 A third objective was to identify the social and cultural context of the Deichmanns' work and lifestyle. The thematic focus here is the artistic milieu in which the Deichmanns worked. Through them, the contact between the crafts movement and the wider artistic movement in Canada is explored. Their circle of friends in New Brunswick included Millar Brittain, Jack Humphrey, and Kay Smith among other painters, photographers and supporters of the arts who frequently visited and stayed with them.

26 The artistic energy of this "salon" in the Maritimes is highlighted by original drawings and paintings of the Deichmanns by other artists, most of which were originally exchanged for ceramics. We have also included photographs of these friends together. Beyond this, their position as important pioneers in the crafts and as respected citizens of New Brunswick is recorded through examples of their commissioned work, particularly for the Royal Visit of 1951.

27 A fourth objective was to contribute to the recognition of various cultural groups in Canada. The thematic focus here involves the Deichmanns' Danish origin and the influence of this heritage on their work. This was developed through text drawn from interviews with Erica Deichmann referring to their origins. Attention is given to the Scandinavian design elements evident in their ceramics, particularly in the painted designs. We have also included personal and professional memorabilia referring to Denmark, as well as family photographs. This theme is also alluded to in the exhibit design by use of Scandinavian influenced elements, for example, "Danish modern" furniture, which became extremely popular in Canada during the latter part of the Deichmanns' career. Through this project, we suggested an important Danish-Canadian contribution to the arts in Canada.

28 This project furthers our efforts to document the social and cultural context and meaning of the arts and crafts in Canada by focusing on the "pioneers" of the studio crafts movement. In this case, this study of the Deichmanns' career builds a useful foundation to the appreciation of the work of over 100 Canadian studio ceramists currently represented in our collections.