Articles

Frederick Augustus de Zeng:

Glass Pioneer in Canada

Abstract

German-born American entrepreneur Baron (later Major) Frederick Augustus de Zeng (1757-1838) was the first to attempt to establish a glass industry in Canada. He received a special grant of lands along the Indian River at its mouth on Rice Lake, in what is now Otonabee Township in Peterborough County, Ontario, but began his operations on a nearby peninsula, which is today the site of Serpent Mounds Provincial Park.

Major de Zeng had wide experience in glass making and transportation in frontier situations, so his plans were predictably sound. Good markets for window glass were already present and the immediate region was just being opened to settlers. Moreover, he effectively had no competition. He had access to adequate capital and labour, his lands were virtually free, and his chosen site was near plentiful stocks of timber for fuel and to the raw materials needed for glass. At the same time, the possibility of Trent Canal was first emerging.

Nevertheless, in 1820, and after a full season of work, de Zeng's grant was abruptly cancelled by the government, causing him to lose both his investment and his home. The terse reasons given for this action appear to be spurious and de Zeng himself attributed his misfortune to sabotage by local interests. Indirectly, it seems he was a victim of the larger political and social conflicts which marked this postwar period in Ontario history.

Résumé

Entrepreneur américain d'origine allemande, le baron (plus tard major) Frederick Augustus de Zeng (1757-1838) a été le premier à tenter d'établir une verrerie au Canada. Il a reçu une concession spéciale à l'embouchure de la rivière Indian, sur le lac Rice, dans l'actuel canton d'Otonabee (comté de Peterborough, Ontario). Mais il a d'abord établi son exploitation sur une péninsule voisine, où se trouve aujourd'hui le parc provincial de Serpent Mounds.

Le major de Zeng avait une vaste expérience de la fabrication et du transport du verre dans les régions nouvellement colonisées. Aussi ses projets étaient-ils solidement étayés. Il existait déjà de bons marchés pour le verre à vitre et la région immédiate venait de s'ouvrir à la colonisation. En outre, de Zeng n 'avait pas de concurrent. Il avait accès aux capitaux et à la main-d'œuvre voulus, ses terres ne lui coûtaient à peu près rien et à proximité du lieu choisi se trouvaient d'abondantes réserves de bois utilisable comme combustible et les matières brutes nécessaires à la fabrication du verre. Le gouvernement songeait aussi sérieusement à l'époque à améliorer la navigation sur la rivière Trent.

Néanmoins, en 1820, après toute une saison de travail, de Zeng s'est soudainement vu retirer sa concession par le gou vernement; il a de ce fait perdu son investissement et sa maison. Les froides raisons qui lui ont été données semblent des plus discutables et de Zeng lui-même a attribué son infortune à un sabotage orchestré par des intérêts locaux. Indirectement, il semble avoir été victime des grands conflits politiques et sociaux qui ont marqué cette période d'après-guerre en Ontario.

1 This excursion, taken by Samuel Strickland in October 1825 and described in his Canadian classic Twenty-Seven Years in Canada West,2 furnishes the earliest known published clue to an intriguing and hitherto unknown part of Canadian material culture: the first attempt to establish a glass factory in Canada.

2 The first successful glassworks in this country was operated by Amasa W. Mallory from about 1839 to 1840 on a site located 1.6 kilometres west3 of Mallorytown, Ontario, near the St. Lawrence River.4 This seminal event is currently thought to have followed two earlier attempts, both in the Niagara peninsula and involving John DeCow (later known as Decew). In 1828 the persistent DeCow made the first of four failed bids to the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada to establish a glassworks in the city of Thorold (now in Niagara Regional Municipality).5 Later, in 1835, the Cayuga Glass Manufacturing Company was formed by William Hepburn and DeCow in the village of Cayuga (now in Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Municipality), but this initiative also eventually died.6

3 This paper presents details, recently discovered by the author, of the earliest attempt known yet to establish a glass factory in Canada, including a selected biography of the proponent, a technical description and evaluation of his proposal, a summary of the outcome of his scheme, and a concluding discussion.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2The Entrepreneur

4 Frederick Augustus, Baron de Zeng, was born 7 April 1757 in Dresden, Saxony, son of the High Forest Officer to the King of Saxony. He received a military education.7 In late 1780, he arrived in New York as captain in a regiment of German ("Hessian") mercenary troops aiding the British in the American War of Independence. De Zeng received an honourable discharge from the German command late in 1783 and remained in the United States after the war. He became an American citizen in 1789, whereupon he dropped his hereditary title. In 1792, he was commissioned major commandant of a battalion of militia in Ulster County, New York, thereby acquiring the title by which be was known the rest of his life.8

5 Major Frederick de Zeng is a familiar and well respected figure to many in the United States today, judging by entries on de Zeng in two encyclopaedias,9 special treatment of him in a number of general and specialized historical works,10 and the author's conversations with several New York historians. Surprisingly, however, there is almost no record of the final two decades of his life (1818-1838) and, until now, none at all for the relevant period he spent in Canada from 1818 until 1821 at least. This blackout extends even to the complete omission from his genealogical record of his second family, which he probably started in Canada. In fact two published genealogies11 faithfully record Frederick's marriage in 1783 to Mary Lawrence and their nine children born between 1786 and 1802, but mention neither his second marriage to American-born Wealthy Amanda Seaton in or prior to 1819, nor their three children born between about 1819 and 1823.

6 Frederick de Zeng, as co-owner in charge of operations, was the first large window glass manufacturer in the United States.12 In 1796 he and his partners in the Hamilton Manufacturing Society took over and expanded a short-lived glassworks and formed the town of Hamilton (now Guilderland). 20 kilometres west of Albany.13 By 1802, however, de Zeng was proposing another glass factory, this time on the Sawkill River in the Catskill Mountains at Shady, near Woodstock.14 In 1812 he was superintendent of the new Ontario Glass Manufacturing Company at Geneva, New York.15 The directors soon concluded, however, that not even Frederick's "age, character and experience could cause the company to prosper and be profitable."16 (This manufacturing operation is used later for comparative purposes.17)

7 De Zeng is equally known for his work in all aspects of transportation. During 1790-92 he personally surveyed the entire backcountry from Albany to the Genessee River around present-day Rochester. Later he was connected with General Philip Schuyler in establishing and carrying on the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company18 (established in 1792), whose improvements in the Mohawk River valley foretold the great Erie Canal. Employed by Schuyler from 1793-95 at Little Falls, de Zeng was in charge of the 300 workmen19 building the first lock, which today is the oldest preserved lock in the United States.20 At Woodstock, he planned and promoted what became the Glasco21 and Ulster and Delaware turnpikes, to link his proposed glasshouse with the Hudson and Delaware rivers respectively.22 In 1812 de Zeng championed the Cayuga and Seneca Canal,23 which by 1818 gave Cayuga and Seneca lakes access to tidewater via natural streams and later the Erie Canal.24 To link these same interior waters with Pennsylvania and the south, in 1814-15 he started what ultimately became the Chemung Canal.25

8 It appears de Zeng was trilingual (English, French, and German), and that he could also communicate well with the Indians. In fact, he was commissioned in 1794 to deal with the Indians of the Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga Nations in regard to their reserved lands.26 His character explains much of his success, especially his congenial nature, his energetic and enterprising spirit, and his abundant self-confidence. Inevitably he rose into some of the highest circles in early America, his friends and associates including, besides Schuyler, Baron Frederick William von Steuben, Chancellor Robert Livingston, and Governor George Clinton.

9 In 1815 de Zeng purchased all the land for, and founded, the present town of Clyde, New York,27 perhaps speculating on the construction of the Erie Canal (built 1817-1825). Then in 1818 he built a dam there across the Clyde River and erected saw and grist mills.28 A single silver spoon, engraved "FADZ," and "Auburn [NY] 1818," and still in the possession of his Canadian descendants, suggests de Zeng's affluence in this decisive year and perhaps heralds his impending removal to Canada from his home at Bainbridge in Chenango County29 on the Susquehanna River.

His Proposal

Land and Location

10 "He has ever since August last [1818] spared no pains or expences to discover the best spot in so many respects for the contemplated establishment,"30 Frederick de Zeng "of Smith's Creek"31 (now Port Hope) in Upper Canada would write of himself on 6 March 1819. He was petitioning for a special grant of lands "to establish a window glass manufactory," as he was "desirous to spend the remainder of his days in the dominions of His Britanic majesty."32

11 In support of the factory, he noted, a sawmill and stamping mills ("for the use of stamping the materials for making and building Furnaces & Crusibles &.&.") would be essential, "to which a gristmill will be added for the convenience of the workmen (as well as to keep them at home at their work)." Failing this, de Zeng asked to be "considered only as all other emigrants are—, wishing to settle and remain as a farmer & miller in His Majestys dominions."33 De Zeng was proposing to establish a small industrial community.

12 On 11 March, just five days later, the following decision in favour of 61-year-old Major de Zeng was taken in York (now Toronto) by Sir Peregrine Maitland, the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, in Council:

13 The residency requirement in this order relates to the fact that only British citizens could then own land in the colony of Upper Canada; the naturalization period for citizens of the United States was seven years.35 De Zeng was resident "from the day of the order in question."36 To be considered for a grant in the first place, de Zeng would also have had to swear oath of allegiance to the British Crown,37 which he did.38

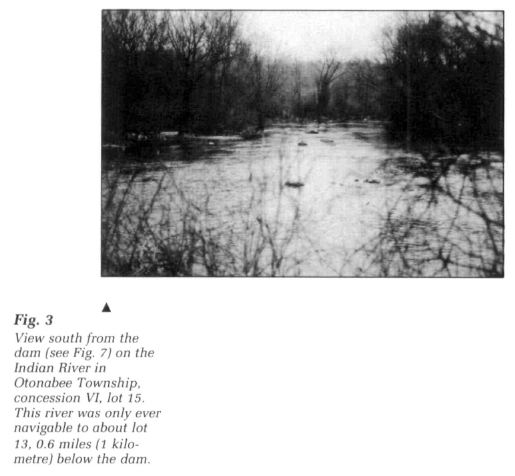

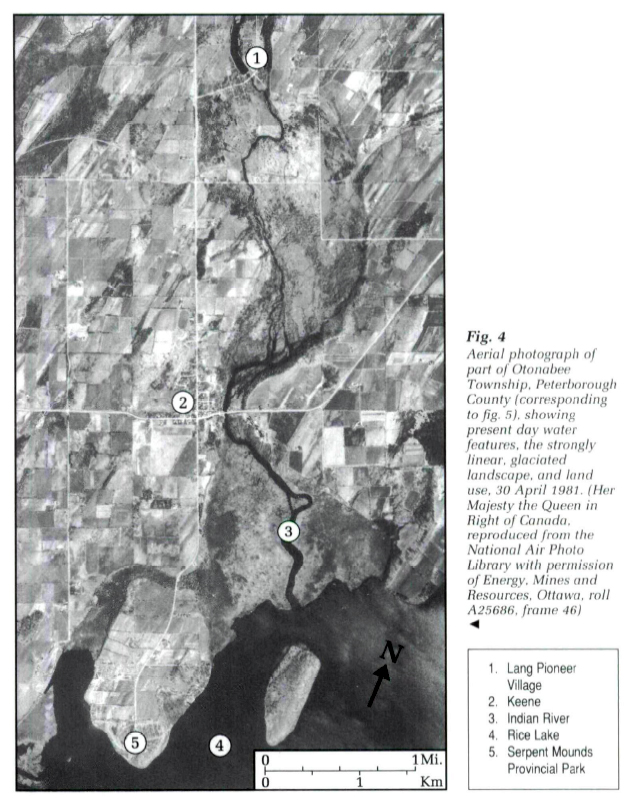

14 The general location proposed for his enterprise is only vaguely described by de Zeng in his petition, reflecting the absence of a township survey. The entire region was wilderness that had only just been acquired by treaty from the Mississaga Indians on 5 November 1818.39 Later information, however, places his proposal in the valley of the Indian River40 near its mouth on the north shore of Rice Lake, in what then was the Newcastle District of Upper Canada and what today is Otonabee Township in Peterborough County, Ontario.

15 The survey for Otonabee Township was completed by Richard Birdsall on 8 December 1819,41 enabling for the first time a clear description of the proposed 500-acre (200-hectare) glassworks site.42 The core was the water-power site ("mill seat") located on lot 15 in concession Ⅵ (200 acres/80 hectares), between the present village of Keene and the Lang Pioneer Village to the north.43 The remainder almost certainly included the adjacent lots 14 (200 acres/80 hectares) and western half of lot 13 (100 acres/40 hectares).44

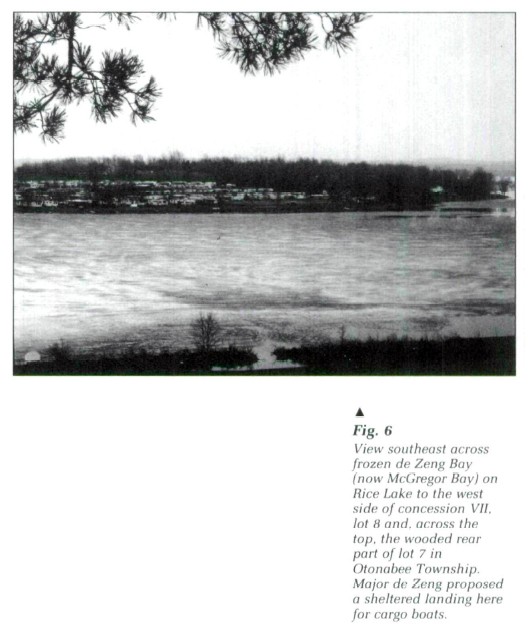

16 Unfortunately, de Zeng was forced by circumstances to make "his first stand" on a peninsula on Rice Lake, in concession Ⅶ of Otonabee, several kilometres overland from the site of the proposed glass factory. His intention was to make a sheltered landing in de Zeng Bay45 (now McGregor Bay) for cargo boats, very likely at the present broken lot 8 (139 acres/ 56 hectares)46 back from the tip of the peninsula.47 However, he actually started his operations on what became broken lot 7 (50 acres/20 hectares),48 the eponymous de Zeng Point49 (now Roach Point), in Serpent Mounds Provincial Park.50 De Zeng's entitlement to these new lots, 7 and 8, was the loyalist right to 400 acres (162 hectares) he purchased51 from brothers Duncan and Jacob Van Allstine.52

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Raw Materials

17 The Otonabee site was well situated with respect to the raw materials needed for glass manufacture. This especially included timber for fuel, as well as the three main constituents of basic glass: silica (in the form of sand), an alkali (soda ash or potash), and lime.

18 Large quantities of timber would be needed for fuelling the furnaces, either as fuel wood or processed into charcoal,53 as a source material for potash and, converted into lumber, for crates and general construction. In fact many glass factories of the period eventually closed for want of timber54 and in Europe, glassworks were still generally considered forest industries.55 De Zeng projected his wood requirement at 3000 cords per year (7200 cubic metres per year),56 which translates into a minimum annual area harvested of 75 acres (30 hectares).57 At this rate, his 3000 acres (1200 hectares) of leased woodlands represented as much as 40 years' wood supply. By comparison, the Geneva glasshouse owned exactly half this amount of timberland, or 1500 acres (600 hectares), when it began in 1810.58

19 The forest resource in Otonabee was not only abundant but of preferred quality. Broad-leaved species, desirable as fuel because of their high energy value, predominated. Richard Birdsall's 1819 logbook for the survey line between concessions VI and VII from lots 13 to 15 alone makes reference to maple (sugar), beech, oak (white or red), basswood, elm (white), and black ash; the coniferous species, better for construction lumber, were pine (eastern white) and hemlock (eastern).59 Nearby settlers were also potential suppliers, especially because grantees were legally bound to clear part of the forest from their property as part of Maitland's "settlement duties."

20 Reasonably pure silica sand is available throughout this extensive and varied area of glacial drift, certainly adequate for the quality and quantity required for a glass operation in the early nineteenth century. In recent years Otonabee sand has in fact been used by the glass industry,60 but for such purpose it does contain enough iron to impart a greenish or brownish tint.61

21 A recent map of aggregate resources in Otonabee Township shows deposits consisting mainly of sand62 as near as two miles (three kilometres) overland to the east, and much larger deposits directly on the shore of Rice Lake and along the Otonabee River, which could be brought in by boat. One promising source is a deposit of glacial outwash only two miles (three kilometres) east of the mouth of the Indian River; such outwash deposits are noted for uniform distribution of grain sizes (needed for good quality glass) and horizontal bedding (for ease of extraction).63

22 De Zeng's primary alkali would have been either potash, soda ash made from common salt, or both. Potash (potassium carbonate) can be made by a simple process that involves leaching wood ashes,64 which in turn de Zeng could easily have obtained either as a byproduct of wood fuel consumption in his own blast furnaces65 or from settlers as part of land-clearing operations.

23 In the early nineteenth century, soda ash was being manufactured from common salt (sodium chloride) by the Leblanc process.66 This would probably have been done at the mill site, considering that one of the raw materials at the Geneva glassworks was raw salt.67 Salt tended to be imported in general,68 but de Zeng's supply might well have been local. In eastern Ontario sea salt is found either trapped in the underlying marine-origin limestone bedrock or in solution, leached from the porous limestone by groundwater. This brine solution is encountered near Otonabee today at depths of 100 to 150 feet (30 to 50 metres).69

24 Natural springs sometimes transport brine to the surface. Indeed, an 1818 map, likely known to de Zeng, clearly identifies "salt springs" down the Trent River from Rice Lake (see Fig. 1). Notes to the "Collins Map" of 1790 identify the location as Percy Boom and confirm that "A Salt Spring discharges into this [Trent] River, Three Gallons of the Water makes one Gallon of Salt, the Natives make great Quantities of it.—"70 This is a very high salt concentration, if true.71

25 Lime (calcium carbonate) is manufactured from limestone. Surface outcrops of limestone in Otonabee are numerous along the Indian River—but only there—including some directly on the site of the proposed glass factory.72 In fact, the geologic formation found here has been quarried elsewhere in the province for use in lime production.73

Capital and Labour

26 De Zeng's capital requirements were very large for the time, considering that the Geneva glasshouse, which by 1820 was producing 300 000 to 400 000 ft2 (28 000 to 37 000 m2), had been launched 10 years earlier with US $40 000.74 De Zeng's proposal was nearly as large, 240 000 to 300 000 ft2 (22 000 to 28 000 m2), and he was evidently intending to assume all the risk himself. He offers, however, that "there will be no objections whatever made for some respectable person or persons (old inhabitants of this province) to become interested in the same, when more fully understood."75 Unfortunately, by 5 September 1819, he was in urgent need of financial "relief," and privately appealed (successfully, it appears)76 to know from his son "if you [William] give up or not all ideas to be concerned in my improvements here or not."77

27 De Zeng would also have to import 25 to 30 workers78 from the United States and perhaps Germany, because glassmaking required unique skills obviously not yet available in Canada. For comparison the Geneva operation employed 21 to 22 people, including 10 glass blowers, 2 cutters, 1 mason, 1 pot maker, 1 calciner, 1 pot ash maker, 1 blacksmith, 1 carpenter, and 3 to 4 labourers.79

Markets and Transportation

28 In the United States, the use of glass in windows was becoming widespread by 1790, and by 1820 there were 18 window glass factories.80 In Canada in 1820, where the population of Upper Canada alone was about 128 000,81 Frederick de Zeng would have been the first manufacturer of glass and thus have enjoyed an absolute monopoly. If required, he could also have counted on tariff protection from American imports, although half of the established glasshouses in the United States had failed between 1815 and 1820 as a result of a general depression. De Zeng's only nearby competition would have been the one remaining glassworks in western New York, at Geneva, but that factory was already selling two-thirds of its output locally, and its lease in any case had just been acquired (in 1817) by his son William.82

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 529 De Zeng's main problem in the young province of Upper Canada was the poor state of transportation.83 To reach settlements along Lake Ontario and points beyond would require transshipment over what were then just trails from the south shore ol Rice Lake to either Cobourg (called Hamilton before April 1918)84 or Port Hope (called Smith's Creek before 1820),85 in either case a distance of about 13 miles (20 kilometres).86 Locally, however, de Zeng would have immediate access to about 40 miles (65 kilometres) of navigable water between the present sites of Peterborough and Hastings,87 in an area that was just then being surveyed and opened for settlement.88 As events unfolded, however, it was 1825 before the total population for all the townships north of Rice Lake would pass 2500.89

30 In the long run de Zeng was confident that "as in all former similar cases" (alluding to his earlier experiences), new settlers would "rapidly follow" the establishment of his factory, which in time he also knew would tone improvements to the transportation and communication infrastructure and stimulate further development.90 Good waterways would have been especially important for a glass operation at this time and, indeed, defence surveys had already started in 1815 for the purpose of locating a water route through the interior of Upper Canada. In 1819, a survey Lieutenant James P. Catty proved that no good alternative to the Trent existed, arousing high expectations among settlers that the Trent River-Lake Simcoe route, including Rice Lake, would be chosen.91 Frederick de Zeng was undoubtedly among the first and strongest promoters of the Trent Canal.92

The Outcome

31 Problems began for Major de Zeng when he moved to Otonabee some time between March and May 1819 and discovered that his carefully chosen mill site had been made inaccessible to boats, first by timber downed in the Indian River over winter and later by heavy growth of a tall aquatic plant, wild rice,93 which emerged later in the bay at the river mouth. (Evidently, he had neglected to inquire how Rice Lake got its name.) He therefore set up directly at the lake on unoccupied lands. Here on de Zeng Point his purpose was "to secure to himself a proper landing place on this Lake, and to open from the same a land road to said mill seat, and thereby make sure in all seasons of the year of a communication to and from the Lake with the contemplated mill seat & back country." In October, de Zeng "still [kept] a number of hands at work."94

32 The arduous circumstances and isolation took a heavy, though not decisive, toll on the health and spirits of Frederick de Zeng. On 5 September 1819 he confides to William, "it is needless to dwell any longer on a subject which makes me day and night more then miserable, having taken all my spirit and contentement from me so that I scarcely know any more what I am about."95 On 26 December, he admits he has "much deranged [his] health in consequence of [his] hardfare in this here before untouched wilderness for the whole of last season, so that [he is] still unable to leave |his] room." Nor has he any "white neighbours nearer to [him] then about five miles [eight kilometres] distance from [his] habitation96...meaning Mr. [Charles] Anderson, the Indian Trader."97 On 24 January 1820 he has "not...fully recovered [his] health, the fever having.. .settled on [his] eyes."98 De Zeng probably had malaria.

33 De Zeng was worried constantly that his land holdings would be disrupted by the intermixing of reserve lots in the final survey plan, for he needed a compact operation. However, Upper Canada was employing the "chequered plan,"99 which required a certain portion of the land base to be designated at preset intervals for the exclusive use of the clergy or crown. Otonabee Township was no exception. As it happened, lot 8 on de Zeng Point was designated in the survey as a clergy reserve, isolating "all [de Zeng's] improvement... on a broken front [lot 7] from 40 to 50 acres only."100 He still could have obtained a road allowance through this reserve, or leased the whole lot (as it "was not before applied for"),101 but he could never have owned it.102

34 Cut off from his mill, de Zeng petitioned the government in York for a second time. On 26 December 1819,103 he warns that without permission to keep these new lands on the point, he would have "to stop going on any further" in his plans for the glass factory, "as it is altogether inadmissable to transport the necessary timber & fuel for the same any great distance." He further refers to the high costs he already faces. "By no means...is the mill seat...anything more than an artificial one, and to be made so by very great expences only."104 Finally, he proposes to apply one of his two purchased 200-acre (80-hectare) loyalist land rights to the acquisition of lots 7 and 8 combined (189 acres/76 hectares).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 635 De Zeng's plans were finally terminated by the abrupt cancellation of his granted lands on 6 January 1820,105 justified by several flimsy or concocted charges about his lack of progress and even conduct. According to Maitland, in council with the Hon. and Rev. Dr. John Strachan, the Hon. James Baby, and the Chief Justice William Dummer Powell, de Zeng had erected "no Mills," introduced no "Settlers and Laborers," and, moreover, had illegally purchased the United Empire Loyalist (UEL) rights. Most damaging of all, however, was "a report having reached his Excellency" that de Zeng had engaged in "highly improper, and even criminal conduct, since [he] came into this Province," with no further elaboration.

36 De Zeng's reply from Rice Lake was immediate.106 It was true that no mill had yet been erected, de Zeng acknowledged, but in May 1919 he had been explicitly discouraged from doing so before the survey was completed by officials of the government's own district land board, in the persons of Charles Fothergill and Thomas Ward.107 Furthermore, settlers would obviously not be brought in to operate the glass factory, de Zeng reminded Maitland, until it was built. Yet de Zeng had made progress, "not saying any thing how great the troubles and expences are to make many improvements at the same time, and on different situations or spots in such an untouched wilderness, and all this in one short season..." He had not only built "a home for himself"108 but was "fully prepared next spring to lodge a number of workmen, and for keeping the necessary teams [of horses]." In addition, he had "actually engaged a millwright to go to work as soon as practicable...and made other necessary preparations in purchasing & transporting provissions here." To support his claims, de Zeng even challenged the government to send am inspectors they so wished, "Charles Fothergill excepted."

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 737 De Zeng asserted that he was ignorant of any law prohibiting the sale of UEL rights, and leapt to the defence of the Van Allstine boys too. Why should he have thought otherwise, since the buying and selling of these land rights was not only widespread in Upper Canada,109 but his own letters to the government itself show that he had always voluntarily and openly reported his transaction.

38 The final odious, unspecified "charge of criminality" was properly dismissed by de Zeng as the work of:

39 No later correspondence has been found on the topic of the proposed glass factory. Nevertheless, de Zeng did gain a measure of revenge in a subsequent land flip. The immediate beneficiary of de Zeng's improvements in Otonabee was the brother, Koswell Seaton.111 of his second wife. Seaton located on lot 7, concession VII on 22 March 1820 and received the patent on 21 February 1821. De Zeng bought back the property on 19 May, and in turn resold it just over five months later, on 29 October, for eight times what he himself had paid. The next record of de Zeng is in the summer of 1824, when he is back again in New York state.

Discussion

40 Frederick de Zeng came to Canada to pursue an economic opportunity at a time, just after the War of 1812, when the economy in both countries was depressed; in the United States the glass industry in particular was being savaged. Nevertheless, de Zeng clearly intended to stay and settle in Canada, since he knew he could not get title to his properties for seven years, by which time he would be 68; indeed, he fought to keep his residence on de Zeng Point even after losing his lands for the proposed glass factory and mills. The moment of his arrival, August 1818, coincides exactly with the arrival in Upper Canada of the new Lieutenant Governor, Sir Peregrine Maitland, who restored the right of Americans to take the oath of allegiance and thus acquire land.

41 De Zeng's prospects for establishing the first glass factory in Canada were excellent, if only because he himself was one of the leading glass and canal men in North America. He would have a monopoly of existing markets, with good prospects for expansion. In addition, his personal resources and connections would help ensure that his capital and labour requirements would he met, and the land would be free or nearly so. The location he selected was fairly remote, but Otonabee Township was just being surveyed for the first time and thus opened for settlement. More important, his site was near the raw materials he needed, especially timber, but also sand, limestone, and possibly salt. Transportation was a problem but improvements to the Trent River were being actively considered.

42 Still, the venture failed and de Zeng lost both his home and his investment. The immediate reason, of course, was the mere fact he had the rug pulled out from under him—his land grant was revoked. The reason why, however, is closely related to the political and social conflicts which marked the period.112 First, de Zeng was American. Anti-American feeling was still rife after the war, especially at the government level, making the "alien question" (the exclusion of American immigration) the main focus of postwar dispute in Upper Canada. Indeed, the government still feared for the province's ability to repulse any future American invasion in the sparsely settled colony. Only the arrival of Maitland and the lobbying of powerful self-interested landowners like William Dickson113 had created an opening for Americans, including de Zeng, in the first place.114 In this atmosphere de Zeng would get little benefit of doubt.

43 Second, and a special concern of Maitland's, was the fact that large tracts of granted land in Upper Canada were being held in an unproductive state by speculators, thereby impeding settlement and progress and exacerbating the security problem alluded to above. Accordingly, even the suspicion of not proceeding with satisfactory baste would be—and was, in de Zeng's case—harshly dealt with.

44 The final factor is a more parochial and personal one. It involves conflicts of interest among local men who, in an area and at a time when development schemes abounded, had ideas of their own to promote. De Zeng believed his plans were sabotaged by such competitors, who evidently succeeded in turning the minds in York against him, either by submitting false reports or by exaggerating the extent of his normal operational difficulties. De Zeng's illness contributed to his problems too, not so much by slowing his progress, but by keeping him from appearing in person at York at the critical moment to defend himself and use his well-honed powers of persuasion.115

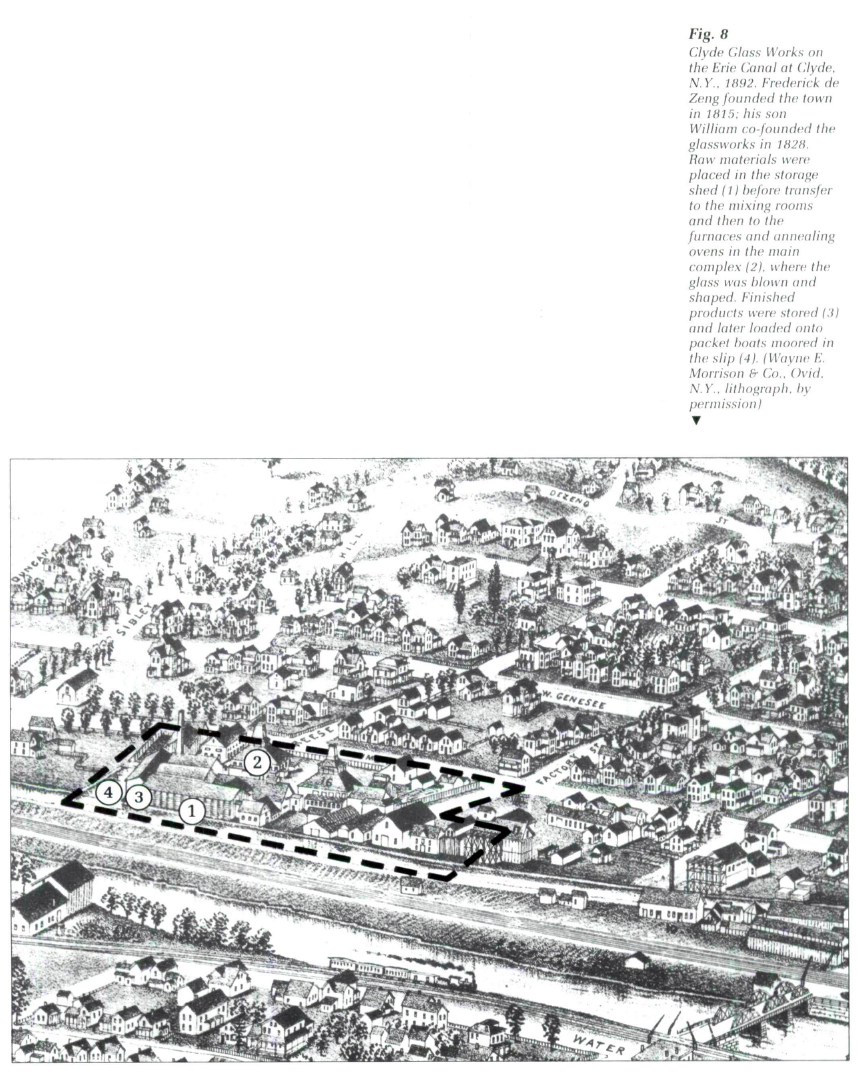

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 845 De Zeng's relatively short stay in Canada, from his first exploration in August 1818 until some time before 1824, was full of accomplishment. He made an honest and courageous attempt to establish in Canada its first glass factory and one of its first heavy industries of any kind. In so doing he must have been among the very earliest promoters of the Trent Canal. Lastly, de Zeng was a true frontiersman, hacking his home from the wilderness and starting a family116 to become the first settler in Otonabee Township117 and among the first in Peterborough County.118

46 Major Frederick Augustus de Zeng died at Clyde, New York, on 25 April 1838, aged 81. His achievements continued during his final years in America. In 1824 he was instrumental in bringing the famous American Shakers religious community to western New York and in fact suggested the site of the new colony at Sodus Bay on Lake Ontario.119 In 1828 he laid the cornerstone for a new glasshouse, co-founded by his son William that was to operate continuously for almost a century. Here on the Erie Canal at Clyde, New York, it could be said, was built the first glass factory in Canada.

I gratefully acknowledge the help I have received from innumerable archivists, librarians, historians, genealogists and government officers in Canada and the United States. The National Archives of Canada, in Ottawa, and the Archives of Ontario, in Toronto, deserve special mention. I also wish to thank Mrs. Elizabeth Walsh of Vancouver for first bringing to my attention the name of our common ancestor, Frederick A. de Zeng. Above all, I am indebted to my wife, Caryl, for her intelligent and enthusiastic assistance in the research for and review of this paper.