Articles

Photographic Archival Sources for Costume Research

Abstract

Photographs are an essential component in the interpretation of costume. Patterns and designs record what was conceived; surviving artifacts present what was produced and delivered; business records document volumes and costs; catalogues and prescriptive materials portray ideals. Photographs contribute a unique dimension to the study of what was actually worn, how it was worn, and what it meant to the wearer and the viewer. Through their pictorial content, presentation format and accompanying documentation, photographs provide essential clues to the social context of dress and to the relationship of costume to other material artifacts. This article will explore photographic sources for costume research, stressing the importance of studying photographs in the context of archival collections, and it will suggest factors to be considered in the interpretation of photographic images.

Résumé

Les documents photographiques constituent un élément essentiel de l'interprétation du costume. Les patrons et dessins témoignent de ce qui était conçu, les objets préservés montrent ce qui était produit et livré, les archives de commerce font état des coûts et des quantités, alors que les catalogues et documents à caractère prescriptif représentent des idéaux. Les photographies ajoutent une dimension unique à l'étude du costume qui était effectivement porté, de la façon dont on le portait et de ce qu'il signifiait, tant pour la personne qui le portait que pour les autres. Par leur contenu visuel, la manière de présenter ce contenu et la documentation qui les accompagne, les photographies fournissent de précieux renseignements sur le contexte social du vêtement et sa relation avec d'autres objets matériels. Cet article présente les sources photographiques pour la recherche sur l'histoire du costume, soulignant l'importance de l'étude des photographies dans le contexte des collections d'archives, et il suggère des facteurs à considérer quand on veut interpréter les images photographiques.

The Photographic Medium and Portraiture Formats

1 Just as the knowledge of materials and techniques in textiles and construction contributes to the study of costume, an understanding of the history of photography helps in assessing the validity of particular photographic images for specific costume research projects.1 It reveals the technical constraints, and the formal and stylistic considerations, that influenced the making of the image.

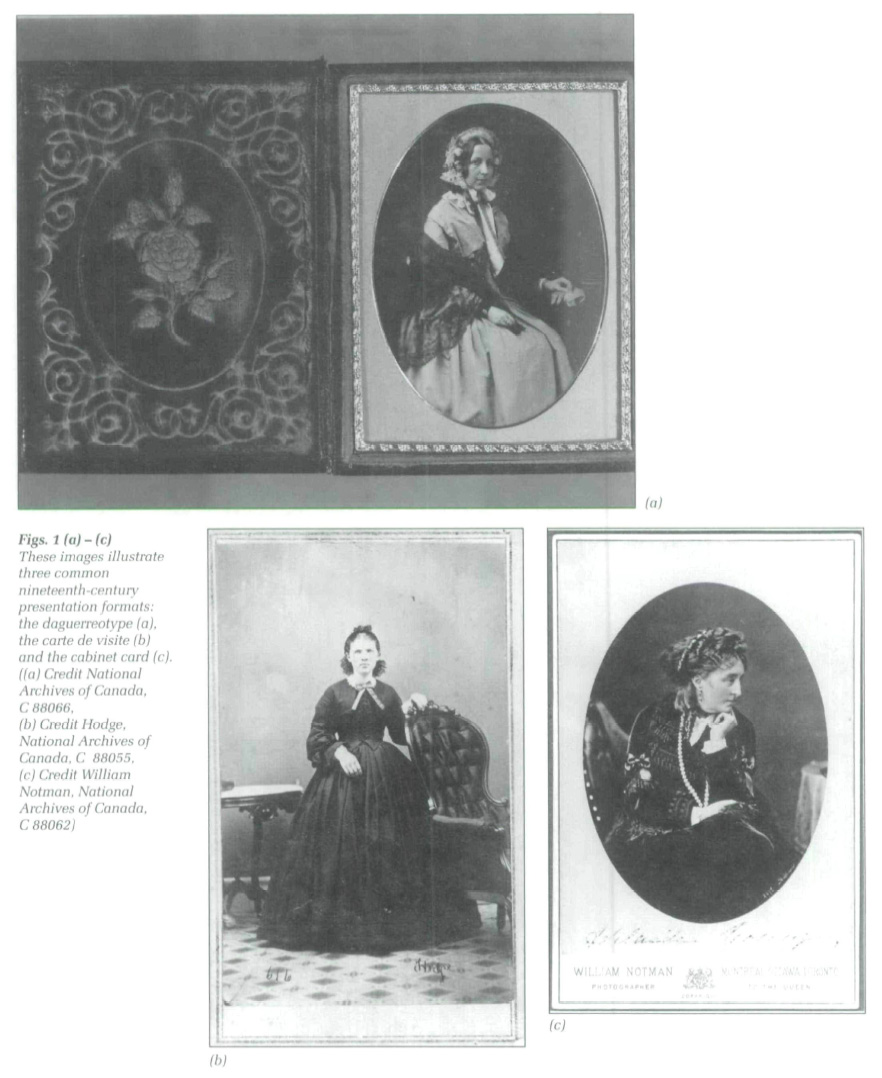

2 Photography is the registration of an image on a light-sensitive surface. The earliest photographic process, the daguerreotype, was introduced in 1839. The image is registered on a metal plate and has a characteristic mirror-like appearance. The daguerreo-type found widespread commercial application throughout the 1840s and 1850s as a medium of portraiture (Fig. 1(a)) then lost popularity in die 1860s. It was followed by the ambro-type where the image was registered on a glass support, and then the tintype. Usually mounted in small cloth-lined cases, their presentation format was derived from the traditions of miniature portrait painting.

3 As new photographic processes for paper prints were introduced throughout the nineteenth century, the fashionable presentation formats for studio portraiture also changed from the carte de visite, which first appeared in the early 1860s (Fig. 1(b)) to the cabinet card of the 1880s (Fig. 1(c)) to the studio folder. 'Carte de visite' refers to the size of the card (about 4 x 2 1/2 inches) on which the photograph was mounted. Cabinet card refers to a mount, sized about 6 x 4 inches.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 24 Both the photographic process and the presentation format contribute to the dating of a photograph. They reflect the artifactual aspects of the photograph. They also remind us that the sitter had expectations of the material context in which the portrait would appear - hung on a wall, inserted into an album, or perhaps placed into an intimate locket. The selection of appropriate pose and costume were influenced by the interplay of contemporaneous fashion, the hand of the photographer, the self-image of the sitter, and the prevailing conventions of portraiture.

5 Over the course of the nineteenth century, technological developments took photography outside the studio and beyond portraiture into documentation, advertising, journalism, ephemera and art. Photography became accessible to the amateur with increased portability of cameras and equipment, commercial processing of film and reduced costs. As industrialization fostered the changes that resulted in the mass-manufacture of costume, technology promoted the diversification of photography.

6 As the range of both personal and commercial photographic applications grew, so did the variety of subject matter. From portrait studios, to worksites, to public events, to homes and places of leisure, photography has recorded the dress of those who knowingly and unknowingly appeared before the camera lens. For the researcher, once the area of costume study has been determined, the next step is to identify the most likely photograph occasions in which it might have appeared, and the most likely archival sources.

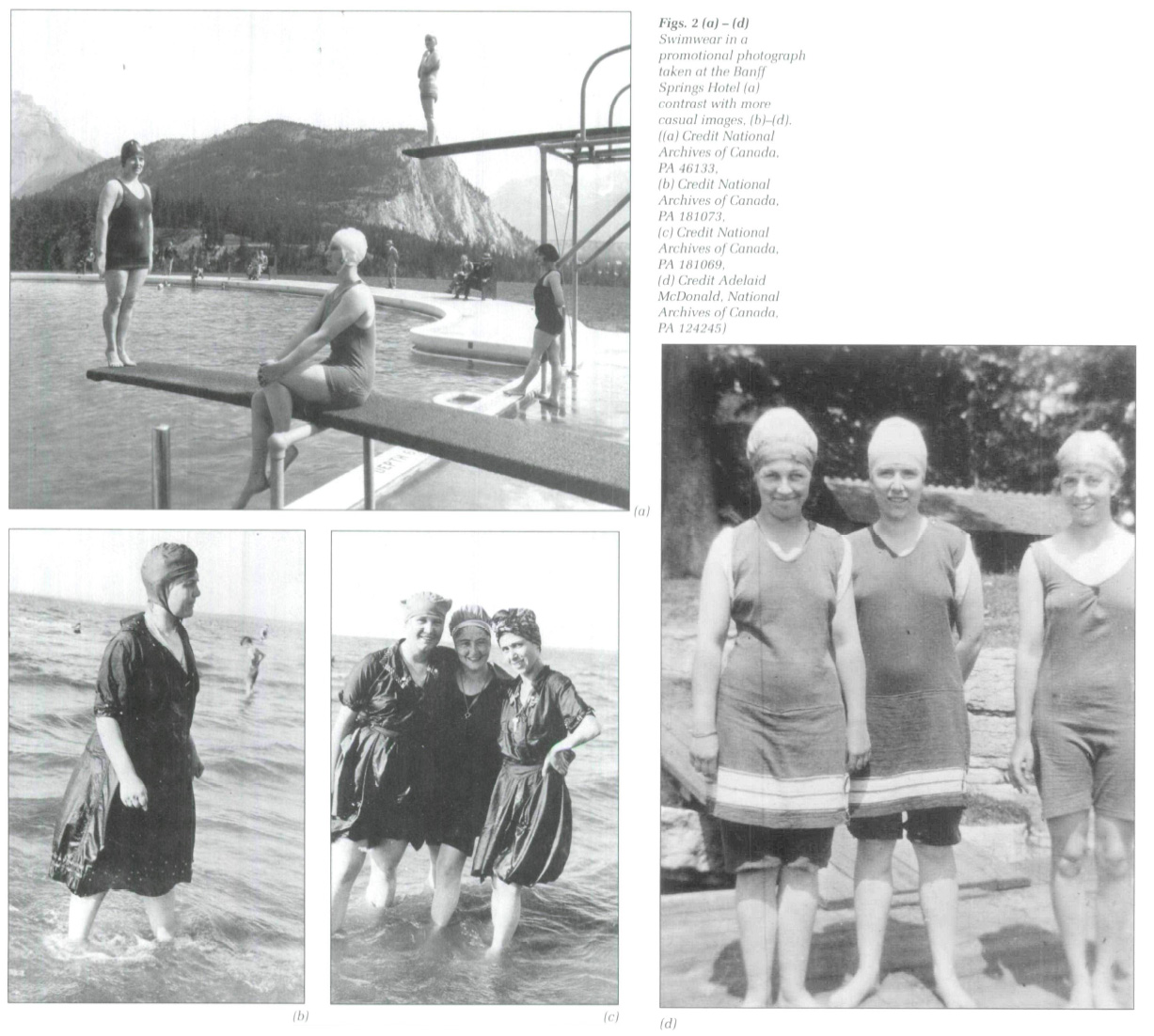

7 Photographic collections provide a range of sources for comparative study, complementing prescriptive fashion found in catalogues and promotional materials. For example, wedding dresses appear in formal portraits taken by professional photographers commissioned by the family. The search for wedding portraits will take the researcher to family photograph collections and to commercial photographers' collections. Other costume subjects might logically lead the researcher to collections which originated from newspapers, business organizations, social agencies, or governments. The researcher must judge the context in which the costume would have appeared and been photographed, and the context in which the images were created and preserved. Another example might be swimwear (Figs. 2(a)-(d)). The informality of snapshots reveals the actual fit and posture, which contrasts with the idealized, and contributes to interpretation for historical accuracy. This group of photographs includes a promotional image taken at the Banff Springs Hotel for Canadian Pacific Railways in 1928; two images from an album containing extensive coverage of beach scenes at Grand Beach, Lake Winnipeg, Manitoba, taken for Canadian National Railway, ca 1914; and a snapshot from an album of photographs taken by summer camp participants in 1917, found among the archival records of the Young Women's Christian Association.

The Archival Context

8 The value of a photographic image as documentary evidence is greatly enhanced by the context in which it is found.2 This archival principle of 'respect des fonds' refers to the integrity of the original grouping. Together with the concept of provenance, which refers to the original source of the document, interpretation proceeds from all that is found within proximity and all that may be revealed through original order. Thus, the information about costume in a single image is enhanced both by the knowledge of the photograph's origin, and by the information contained in other photographs, correspondence, diaries, logbooks or other materials that belong with it.

9 In most archives, subject-oriented indexes, guides and finding aids provide researchers with access to specific components of archival collections. These tools are a convenient mechanism for initially locating images relevant to particular interests. Once located, however, these images must then be examined in the context of their grouping, and with knowledge of their origin, to reveal their full documentary potential. For example, what begins as a single portrait photograph then becomes part of a grouping when it is pasted into an album. This album is then recognized as part of a larger grouping when it is found among family papers. Each successive grouping contributes to the understanding of the costume worn in the portrait; the more that is known about the family being photographed, the greater the information about the subject. The added insight derived from this expanded context reveals more about the subject, the original purpose behind the photograph, and the subsequent meaning that it had for its keeper. It can serve to verify the researcher's interpretation of an image subject for consistency or variation within its grouping.

10 The following sections describe types of archival photographic collections which may be particularly relevant to the study of costume, with suggestions outlining some of the limitations and advantages inherent in these holdings for costume interpretation. The observations are intended as a guide only, reflecting frequently encountered patterns. By definition, archival collections are unique, demanding caution before proceeding with any sweeping generalizations.

Personal and Family Collections

11 Photographs in family collections appear in albums, snapshot groupings, scrapbooks, with correspondence, and as autographed presentation portraits and memorabilia. The fact that they have found their way into archival repositories suggests that the originators were conscious of the social status of the family. Many of these collections were acquired as donations directly from the family, suggesting that the family recognized its place in the community, intentionally preserved its documentation, and a self-ascribed continuity.

12 The cross-section of society represented in these collections tends, therefore, to be limited to those with a sense of family lineage, and with disposable income to obtain photographs. It also suggests there has been a continuity of family home where the material was physically collected and preserved over time. For example, an extensive family photograph collection in an archival repository more likely originates from an established family with property than a migrant worker's family. This parallels the availability of better quality and special occasion costume as extant artifacts in museum collections.

13 Family collections allow costume researchers concerned with the identity of the wearer to expand their profile of the individual depicted by referring to other photographs, as well as diaries, letters, scrap-books and clippings that form part of the collection. The occupation, social and economic status, and position within die family can often be determined. Anecdotal information about the events photographed and the costume worn might be found in personal papers accompanying the photographs, and may perhaps recast the interpretation of the costume.

14 For example, the costume wearer's aspirations, ideals and cultural values can be reflected in a diary, or in a scrapbook that contains images of royalty, sports heroes or pop stars. The researcher might then ask: what were the wearer's models? how successful was the wearer in emulating these models? was this due to skill, economic status, or availability? or was this due to the influence of a parent or authority figure or outside dress code that controlled what was actually worn in the photograph?

Professional and Studio Photographers

15 The photographer's studio has been an integral part of services in the community. As a creator of images and as a businessperson, the successful photographer identified a client base and integrated their image of themselves. Individual and family group portraiture, wedding and special event photos form a large component of these collections. Their continuity and comprehensiveness make them particularly valuable as research sources.

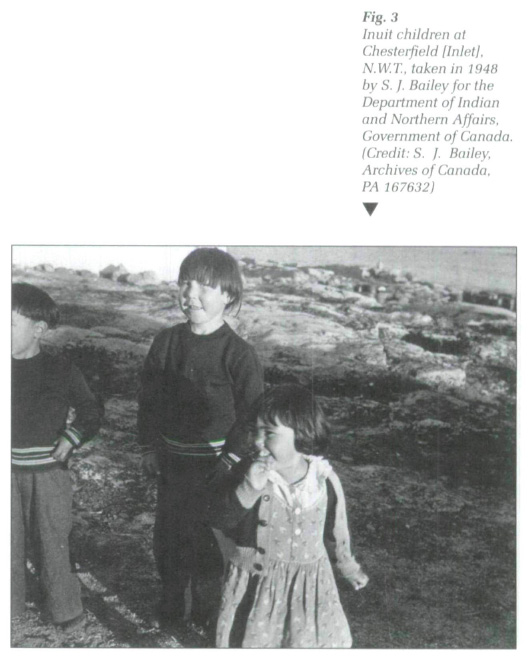

16 These collections are most often acquired by archival repositories as a complete working record of a studio. While the finished prints were sold to the client-sitters and might now be found scattered in family collections, the negatives remained part of the photographer's inventory and have sometimes made their way into archival collections intact. They are often accompanied by the appointment logbooks which identify the sitter, the date, the format and extent of prints ordered.3

17 Costume in studio collections may be limited to formal attire and frontal views, since the photograph occasion is governed by the conventions of portraiture. However, the strength of these collections lies in the continuity, comprehensiveness and identification that they offer as a source for comparative costume study. As relatively complete working records, they are not subject to the personal selection process that influence the composition of family collections. With the context of studio portraiture established and constant, the researcher can consider other variables such as date, location, or peculiarities of style or detail.

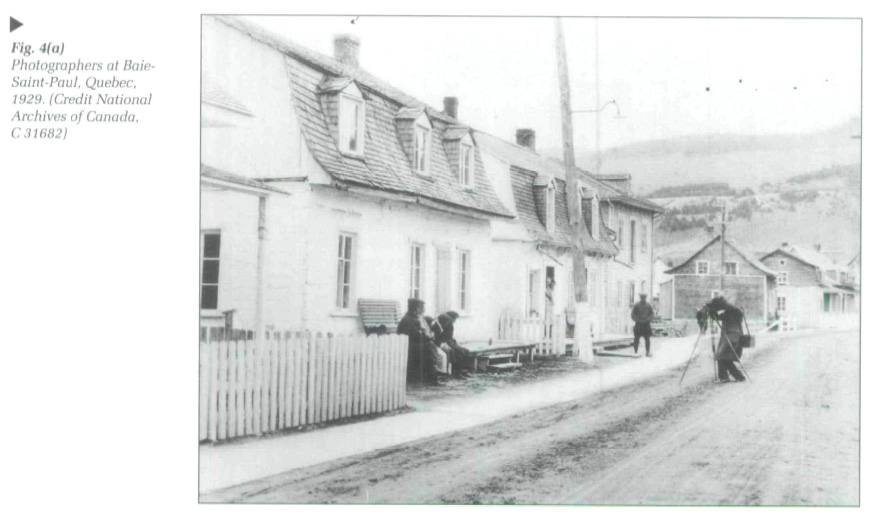

Amateur Photography

18 Rather than addressing casual snapshooters, this section deals with the serious amateur who approached photography as an area for study, art and craft. Although this work is less abundant and less consistent in its content and internal organization than some of the other collections discussed, the unique perspective from which the amateur approached the photograph makes this a viable alternate source for costume study.4 The amateur photograph is more likely to exist outside the approval of public tastes or business practice, since there was no reliance on selling prints to earn a living. Stylistic innovation, obsessive observation and devoted perfection can run free in the realm of amateur photography driven by the love of art or craft or subject matter. Spontaneity, naturalness and familiarity are more likely to appear in this domain. The very personal perspective of the serious amateur enriches the study of dress in informal or intimate situations, un-posed postures or pure flights of fancy.5

19 Due to the eclectic nature of amateur collections, patterns of research and possible findings are more difficult to predict. This is in contrast to studio collections, for example, where identification and organization are inherent in the structure of this type of photographic production.

Press Photography

20 Press photography appears in collections originating from newspapers and photo-journalists. Newspapers are among the most prolific creators of photographs. As negatives taken by staff photographers are taken out of active use, or as newspapers cease to operate, the large collections of negatives (sometimes with accompanying contact sheets or assignments sheets) may be acquired by archival institutions.

21 These collections are most often organized chronologically by assignment, containing all of the negatives in a photo shoot. While only one cropped image may have been reproduced in the original publication, die archival collection allows the researcher access to a wealth of additional images that were rejected in the editing process. It provides a more comprehensive context, and the possibility of incidental information that may be revealing.

22 This photography is event-centred or story-driven. The subject or perspective must have been considered newsworthy, defining the range of documentation and approach in these collections. Captions that usually accompany these photographs not only provide extensive identification, but the vocabulary and language structures employed reveal cultural values that have informed the viewpoint from which the photograph was taken and the viewpoint from which it was interpreted in its time.

Organizational and Business Records

23 Archival documents from corporate bodies include financial and administrative records, correspondence, and promotional materials. Related photographic holdings document the workplace, production processes, product lines, and organizational activities. As costume sources, these collections document dress in the work context, as well as in group activities such as company picnics, promotions and celebrations.

24 The records of community service organizations include rich photographic documentation on members and activities. Groups include religious organizations, benevolent societies, sports and recreational associations, multicultural organizations and educational bodies. These collections tend to cover organized activities which are repeated at regular intervals, and therefore allow costume comparisons over time. Examples include panoramic group portraits taken at annual conferences, or photographs documenting groups at summer camps, or sport teams, showing baseball uniforms, gymsuits and swimwear.

Government Records

25 Government departments and institutions have been prolific producers of photographic collections. The National Archives of Canada in Ottawa is the official repository of Canadian federal government records, including large photographic holdings from federal departments. Provincial, regional and municipal governments also designate official archival repositories for their inactive records.

26 These public collections served a precise purpose that can be connected to stated departmental mandates. They are also often well-documented through captions, and comprehensive in spanning time periods. The study of the costume in these images is enhanced by an understanding of the cultural values that are reflected in the objectives of the institution. These values are likely to be echoed in the choice of identifying information appearing with the images, and in the language used in original captions.

27 Government photo holdings which contain extensive research material for the study of costume include those of social service departments or promotional agencies such as tourist offices. The researcher's assessment of the use of costume should include not only the subject content, but also the intended audience and the positioning of the photographer or sponsoring institution in relationship to the photographic subjects, (Fig. 3). This image of three unidentified Inuit children was taken at Chesterfield [Inlet], NWT, in 1948 by S. J. Bailey for the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, Government of Canada. The original caption information found with the image reveals the prevailing perspective from which the photograph was taken, and is essential for the interpretation of dress. It states: "Eskimo children wear far better clothing since Family Allowance was introduced." This caption does not concern itself with providing factual identifying information such as the names of the individuals, nor specific details about the clothing such as fabric, manufacturer or supply source. Its message is the judgement about "far better" clothing, and the apparent benefits of the family allowance. It provided an intended interpretation for contemporaneous viewers, and now provides the researcher with clues to the social, political and economic context within which the photograph was taken.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4Interpretation

28 The mechanical aspects of photography lead to the perception that it is an objective recorder of nature, a faithful witness of reality. However, its artisanal and artististic attributes suggest a more expressionistic view. Whether the aim was fact or fancy, the act of picture-taking involved the process of looking and being looked at. The subject was mediated by cultural values that influenced both the photographer and the context in which the photograph was taken, and the viewer and the context in which the photograph was viewed.

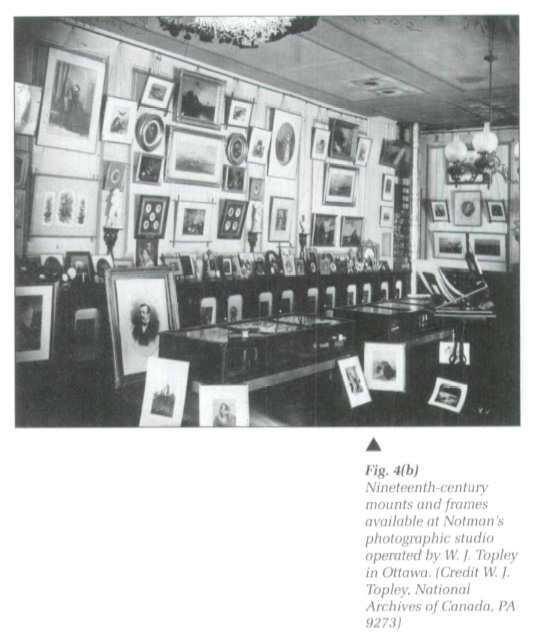

29 Figures 4(a) and 4(b) illustrate significant considerations for the interpretation of costume in photographs, suggesting factors that might influence the choice of costume and how it is worn. They point to photography as a mediator of perception, with a history of portrait conventions. In assessing the costume in a photograph, the researcher can begin by stepping back, to replace the presence of the photographer into the picture (as in Fig. 4(a)). A further step might consider the wearer's expectations about the purpose of the photograph, who will see it and in what context. Figure 4(b) shows the range of frames and mounts displayed in a photographer's studio that reflect the nature of the service that the client is buying.

30 To explore the broader content of the photograph, the researcher might pursue a line of questioning from the perspective of the photograph itself. Who took the photograph? Who was the sitter or subject? Was the photograph commissioned? Were there technical constraints in the production of the photograph? What are the stylistic and formal conventions of presentation? Another tack might delve beneath the factual identification of the image. What was the intended use of the photograph? Who was the intended audience? What was the photograph intended to communicate? Were the individuals in the photograph aware of this purpose or involved in the commissioning of the photograph (as clients, for example)?

31 To focus on the costume, the researcher might ask if any prior preparations were made to dress for the taking of the photograph? From the archival perspective, what were the circumstances that contributed to the photograph's survival and preservation? What was its source and what kind of collection is it now a part of? What does this reveal about the cultural values behind the image? Although the answers to these questions may not be definitive, they do contribute to unravelling the underlying meaning inherent in the taking and viewing of the photograph. This approach to identification and interpretation acquires a broader dimension in support of costume research.

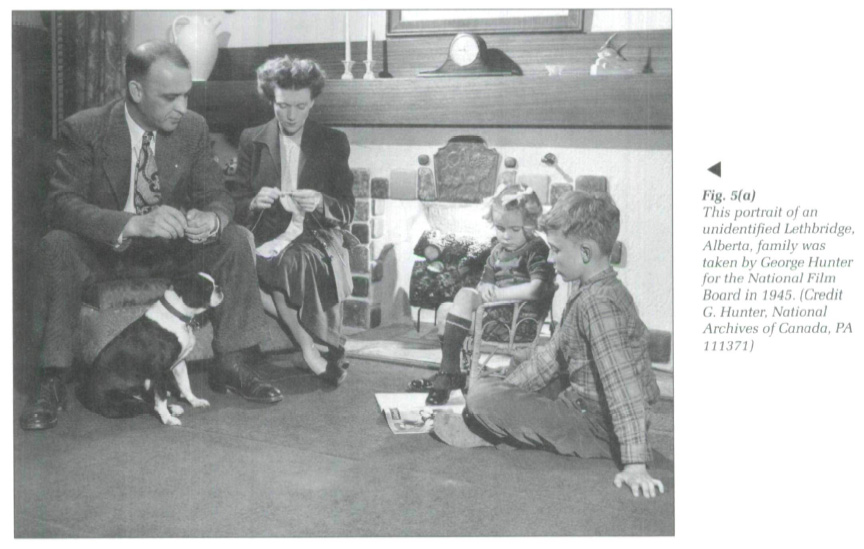

32 In the interpretation of costume, dress is viewed as one part of the system of signs which communicate cultural values and social context. In using photographic sources, the researcher's analysis can focus on the interplay of the conventions of dress and the conventions of photography. Figures 5(a) and 5(b) reinforce the iconographie representation of the model family. Dress is part of the emblematic structure that conveys class, economic status, gender roles, race, beliefs. In the conscious photo occasion, dress and pose work together to place the individual within a system of signification. The image is constructed so that it controls the manner in which it is read by its intended audience.

33 The costume in the photograph is an attribute of the wearer. The act of selecting dress, and the constraints and liberties in that process are essential factors in the interpretation of costume. Archival collections provide the researcher with the clues to that process.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7