Articles

An Uncertain Harvest:

Hard Work, Big Business and Changing Times in Prince Edward County, Ontario

Abstract

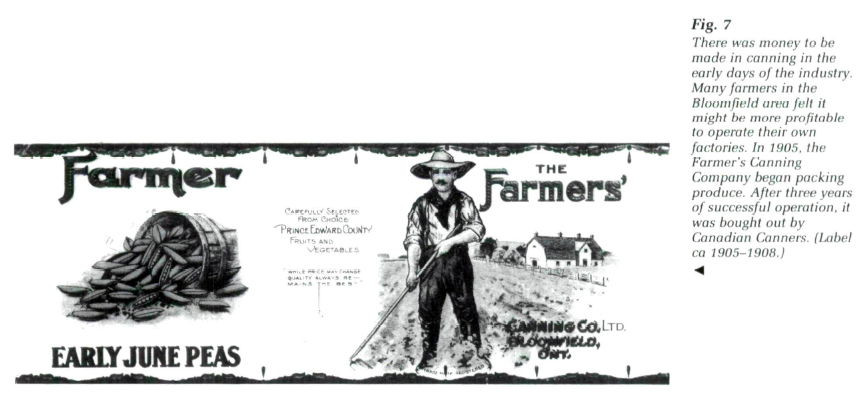

Although Prince Edward County, Ontario is not blessed with particularly fertile soils or the longer growing season enjoyed by other agricultural areas in Ontario, a combination of unique factors conspired to make the region the centre of the canning industry in Canada until the 1950s. The pioneer canners made their money by embracing new technologies emerging from America's whirlwind love affair with machines and through a business acumen fuelled largely by greed. Increasing fragmen-tation of the market for canned goods forced many of the larger firms to merge in 1903. After World War Ⅱ, however, the industry began to rationalize. Prince Edward County, with its relatively poor soils, shorter growing season and small, obsolete factories, simply couldn't compete with the new factories built else-where. The increased ownership of the industry by multi-national corporations, the introduction of frozen food in the 1950s, the buying practices of national grocery store chains, the introduction of new worker and health regulations and the changing work attitudes of Canadians all took their toll on the canning industry of Prince Edward County. Today, there are few traces of the industry that was once everything to this rural Ontario community.

Résumé

On ne retrouve pas de sols particulièrement fertiles dans le comté de Prince Edward, en Ontario, ni la longue saison de croissance dont jouissent d'autres régions agricoles de la province, mais une combinaison de facteurs favorables a contribué à faire de cette région le centre de la conserverie au Canada jusque dans les années 1950. Les pionniers de cette industrie ont su s'enrichir grâce à de nouvelles techniques issues du machinisme américain et à un sens des affaires aiguisé en grande partie par le goût du profit. La fragmentation croissante du marché des conserves a forcé plusieurs des grandes entreprises à fusionner en 1903. Après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, toutefois, l'industrie s'est rationalisée. Le comté de Prince Edward, avec ses sols relativement pauvres, sa courte saison de croissance et ses petites usines désuètes n 'a plus été en mesure de soutenir la concurrence des nouvelles usines rivales. La mainmise croissante des multinationales sur cette industrie, l'introduction des aliments congelés dans les années 1950, les habitudes d'achat des épiceries à succursales multiples au pays, une nouvelle réglementation des conditions de travail et de salubrité ainsi que les nouvelles attitudes des Canadiens à l'égard du travail furent autant de coups portés à la conserverie dans le comté de Prince Edward. Aujourd'hui, peu de choses subsistent d'une industrie qui a joué un rôle primordial dans cette région rurale de l'Ontario.

1 Prince Edward County, Ontario, clings tenaciously to the northern shore of Lake Ontario just out of earshot of highway 401 connecting Montreal and Toronto, one of the country's busiest transportation corridors. Today, the area is primarily a tourist vacation spot famed for its fine beaches, campgrounds and scenic harbours. Hidden from view by the resort signs, though, is the story of an older industry that was once the backbone of Prince Edward County.

2 In the late 1800s, this small Ontario county basked in its privileged position within the fledgling confederation called Canada. Although it is not blessed with particularly fertile soils or the longer growing season enjoyed by other agricultural areas in Ontario, a combination of unique factors conspired to make the region the centre of the canning industry in Canada until the 1950s. During these years, Prince Edward County stood unchallenged as "the Garden County of Canada."

3 During the first years of Confederation, much of modern-day Ontario was still largely forested and devoted its cleared land to grain production, but Prince Edward County was at a zenith in its history. Its land was cleared and settled. A well-developed shipping industry had established itself after decades of lucrative trade in barley grown for the American brewing industry in New York State. And, most of all, Prince Edward County was home to a resilient and enterprising breed of men who gambled and won in the canning game.

4 Canning is a tough business subject to the whims of nature. Drought, pests, and frost are its enduring plagues. However, this was a time of unbridled free enterprise, and the pioneer canners made their money by embracing new technologies emerging from America's whirlwind love affair with machines and through a business acumen fuelled largely by greed. In the first decades of the Canadian canning industry, the business was dominated by companies that were so ruthless in their dealings with each other, their employees and their growers, that many farmers built their own factories to escape these monopolistic practices. This is one of the chief reasons for the proliferation of canning factories in Prince Edward County, an area that had about 30 to 40 plants in continuous operation until the early 1960s.

5 Throughout the period that Prince Edward County reigned as the canning capital of Canada, sweeping economic and technological changes continued to unfold outside its borders. Two world wars artificially prolonged the good fortunes of the area, but, inevitably, changing times took their grim toll on the canning industry of Prince Edward County. However, in the late 1870s these events lay far in the future when a nursery salesman from Prince Edward County, George Dunning, returned home excited about his trip to the United States.

6 The Philadelphia Food Exposition, which he'd visited, had featured a new industry Dunning had only heard about in the briefest detail—the canning of food. The entire eastern seaboard of the United States was caught up in the canning craze.

7 Dunning himself had sampled these new products: canned lobster, salmon and oysters—bounty from the sea that could be kept almost indefinitely; and tinned fruit and vegetables that could be processed when they were in season and then stored for consumption in the bleak, winter months. George Dunning had never seen nor tasted anything like it in his life.

8 Why couldn't this industry be transplanted back to his home town area? Prince Edward County was cleared and settled. Barley was the main crop but the land would grow others. In the 1870s, John H. Allen had started his seed business in Picton, the region's largest community, and already he had developed a considerable business exporting seed peas to the United States. If county soils could grow peas highly prized as stock for growers in the U.S., why not grow the crop for a local canning industry?

9 Also, more and more of Dunning's nursery stock was being planted in the county. Several thousand acres of apple orchards were yielding a harvest that, for the most part, was packed in barrels and shipped to Great Britain. But not all Prince Edward apples left the county in barrels. Apples of inferior quality were sliced and dried in evaporators. Evaporators were beginning to dot the countryside throughout Prince Edward County—an early ancestor of the business that would soon become the mainstay of the local economy.

10 Dunning made his rounds of the county, meeting with local farmers and talking about the crops, the weather and his visit to the United States. Eventually, the bay mare that drew his democrat came to a stop in the shaded lane way of one of his best customers.

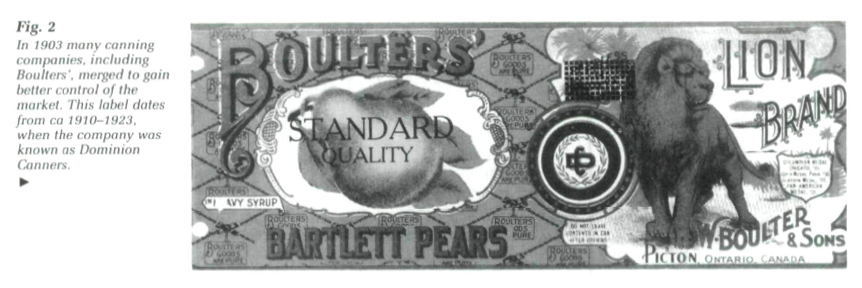

11 Wellington Boulter was not a big man. However, he had a portly stance and monstrous, mutton-chop side whiskers which, coupled with his domineering personality, made him an imposing figure indeed. Boulter was an Orangeman, a staunch Conservative, a justice of the peace and on two occasions, the mayor of Picton. He had made his first money in the loan and insurance business. An ardent Presbyterian, he built a pew facing the other parishioners in the tiny church at Demorestville. "He sat up at the front," remembers a member of the church. "He always faced the congregation. He was an important old guy."1

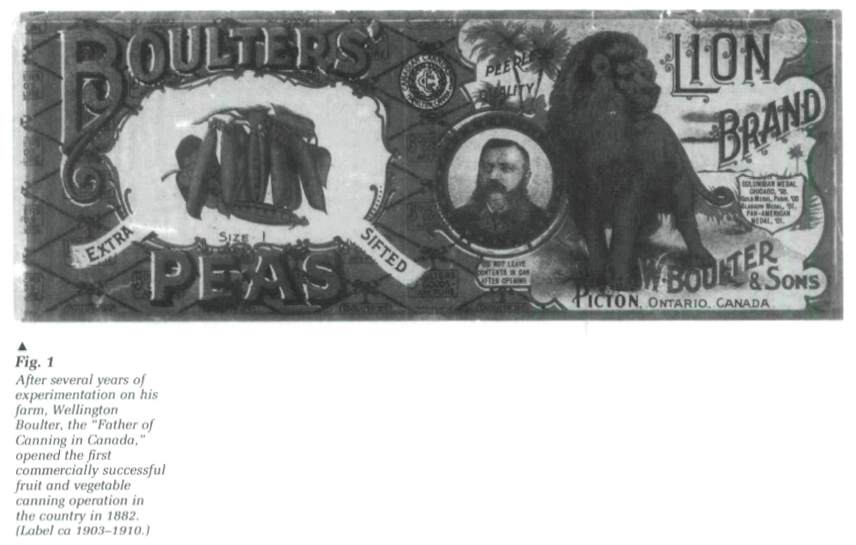

12 Dunning and Boulter agreed to experiment with a small canning operation near the marshy water's edge of Boulter's farm. By 1882, the partners were convinced. In that year they erected a plant opposite the new railway station on Mary Street in Picton—the first commercially successful fruit and vegetable cannery in Canada.

13 There had been earlier efforts in the industry in Canada. By 1840, Tristan Halliday of Saint John, New Brunswick, was canning lobster and salmon. The first fruit and vegetable canning operation started at Grimsby, Ontario in 1879, but folded soon after. A second attempt the following year, in the western Ontario village of Delhi, also met with failure.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 114 It seemed that 1882 was the year a fruit and vegetable canning factory could succeed in Canada. In that year plants opened in Picton, Trenton, Brighton, Lakeport, Grimsby, Dunnville, St. Catharines, Waterford, Simcoe, Aylmer, Chatham, and Strathroy. The factories in southwestern Ontario were scattered and isolated, but within a very few years there were many plants operating in Prince Edward County. This concentration of factories made the county the dominant canning region in these first years of the industry.

15 Fire destroyed the Picton factory three years after it opened, but the partners did not lose their enthusiasm. On the day of the fire they sent an employee to Buffalo to purchase new equipment. Within ten days, they were packing strawberries in temporary headquarters nearby. Despite the setback, their factory packed 25 000 cases of corn, tomatoes, peas and fruit that season.

16 The new factory was one of the largest of its kind but exceedingly small by today's standard—only 176 square feet. In addition, there were two storehouses, a machine and blacksmith shop, a can shop, an office and an electricity plant. A rather battering artist's conception of the factory adorned the letterhead of the Bay of Quinte Canning Company.

Display large image of Figure 2

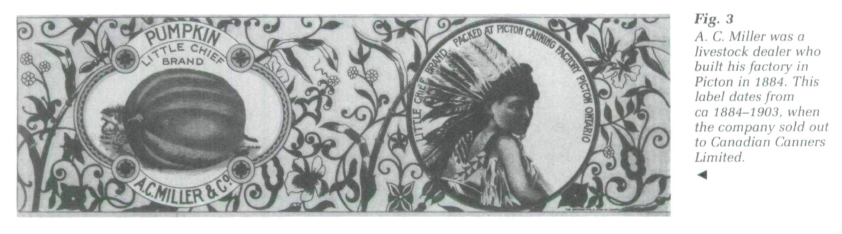

Display large image of Figure 217 Business was so good that the factory on the farm was re-opened with Boulter's 12-year-old son, Ed, in charge. The younger Boulter would fashion his own career within the industry, becoming manager of his father's Picton plant, and later building two others of his own within the county. With the help of another son. Frank, the family expanded their empire, opening a third plant along the Toronto Esplanade at the foot of Cherry Street in 1889.

18 Dunning retired from the business within a few years. His partner Wellington Boulter, however, became a prominent figure in the industry and is acknowledged as its first pioneer. For 12 years he served as president of the Canadian Goods Packers Association, the industry's first representative organization. In 1903, he became a founding member of Canadian Canners Consolidated Companies Limited, later to become Canadian Canners Limited, the largest operation of its kind in the Commonwealth.

19 The Lion Brand produce of W. Boulter and Sons left Picton by ship and rail for western markets in Winnipeg, Vancouver and Victoria; south to Buffalo and Rochester; east to Quebec and on to England. At exhibitions in Paris, Glasgow and Chicago, Boulter's canned goods won international recognition. The company's label, featuring a lion next to Boulter's bewhiskered face, became a symbol of quality around the world. Canning made Boulter even wealthier.

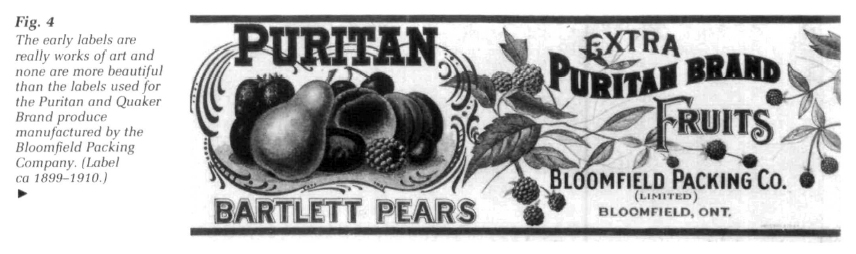

20 Shortly after Boulter opened his Picton plant, two Bloomfield residents built the first of many factories to be constructed in that community. Caleb Noxon and Gilbert Barker soon sold their business, but the new owner, Abraham Saylor, was so successful in his first year of operation that other entrepreneurs rushed to cash in on the profits to be made.

21 It might easily have proved otherwise for Saylor. The industry was in its infancy. No one had a clear understanding of the chemical processes at work. Saylor liked to enhance the colour of his canned tomatoes by using an additive known as cochineal, a crimson dye made from the crushed remains of a beetle native to Mexico and South America.

22 With a flair for colour worthy of painters, the pioneer canners of the industry laced tomatoes with cochineal, and apples with sulphur. When consumers showed a marked preference for white corn, they bleached the vegetable with sodium sulphite. The end product looked appealing but according to old-timers, it tasted awful.

23 But even in its earliest days, the business required some expertise—a knowledge of both machines and processes. There was a certain element of magic involved, all the more enhanced when scientific breakthroughs were applied to the trade. In the early 1800s, the American canning industry borrowed the discovery of eminent English chemist Sir Humphrey Davey. Davey had found that calcium chloride, when added to boiling water, quickly increased the temperature of the liquid. The application of this could be quickly and easily attained, reducing cooking times from five to six hours to less than 40 minutes.

24 Skilled help could not be found in Canada, so Canadian companies raided U.S. operations to obtain many of their senior employees. The Bloomfield Packing Company, built in 1899, hired William Flynn of New York. William M. Miller, better known as "Yankee Bill" served as the processor at the Boulter plant—a position of considerable importance:

25 "Yankee Bill" may or may not have possessed the artistic temperament apparently characteristic of his profession. However, like the rest of his colleagues, he was a man of singular skills faced with unlimited opportunities. In 1884, Miller left the employ of Boulter to become a partner in a new Picton factory. Other Americans emigrated to the county to serve as processors, can-makers and maintenance men. None of the early canners dared open a factory without this imported expertise.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 326 By 1890, there were still just a handful of canning factories in Prince Edward County. Down the street from the Boulter plant, A. C. Miller had not only constructed an even larger factory, he'd lured Boulter's processor, "Yankee Bill," into partnership with him. The new factory packed Little Chief brand goods and their trademark, a 500-pound statue of an Indian Chief in full war dress, stood perched on the roof of the building.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

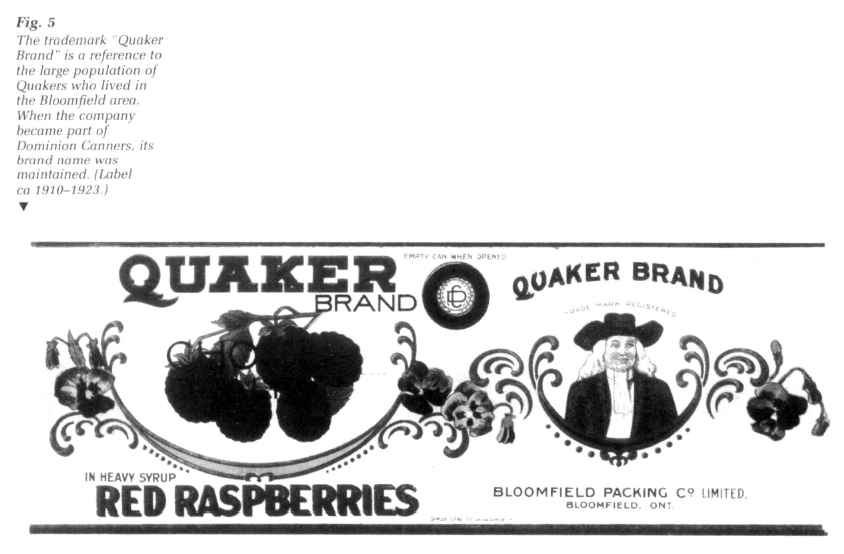

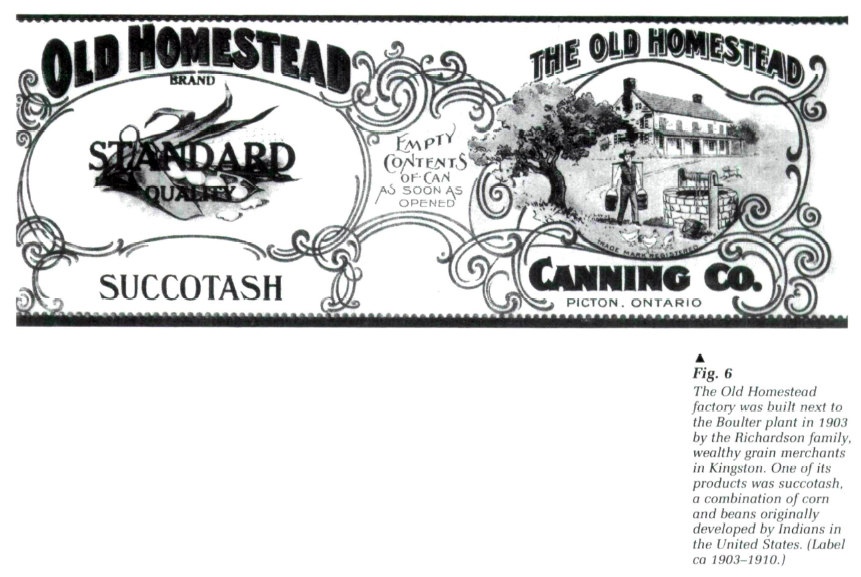

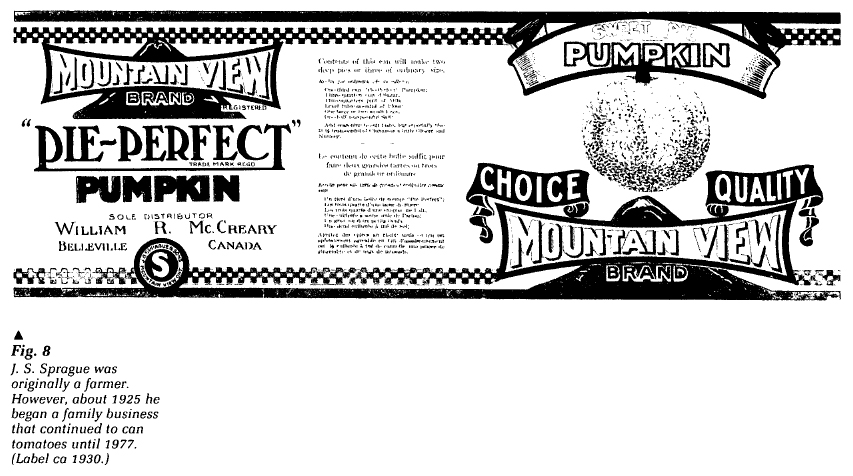

Display large image of Figure 527 The village of Bloomfield, a few miles away, was also an important local canning centre. During the summer months, carts of produce waited their turn to be unloaded at the Saylor plant on Mill street and the nearby Bloomfield Packing Company. The latter was the largest factory in the country, complete with its own can-making machinery. It labelled its produce "Quaker Brand" in recognition of the village's history as an early Quaker settlement. Outside the village limits, John Bedford Orser packed fruit from his orchard into glass jars.

28 As the first years of the new century came and passed, the people of Prince Edward County shared the boundless optimism which typified this age of invention and rapid progress. However, one year in particular brought events of special significance to the Canadian canning industry. That landmark year was 1903.

29 In the spring of that year, 11 leading Canadian canners met in the Waldorf Hotel in Hamilton to discuss amalgamation of their operations. Within two short decades, the canning craze had spread throughout all of southern and eastern Ontario. Dozens of communities boasted one or more factories. But as more and more businessmen rushed to cash in on the money to be made, the market for canned goods became fragmented, profits dwindled and some canning companies were forced to close their doors as quickly as they had opened.

30 The industry's first representative organization, the Canadian Canned Goods Packers' Association, had formed in the 1890s in an attempt to pressure the government for tariff protection against imported American produce and to establish uniform prices and standards of quality upon its members. But not everyone wanted to join, and bumper crops caused prices to fluctuate wildly. The association was too informal an organization to be effective. A new approach had to be taken.

31 The men meeting at the Waldorf Hotel were intent on preserving their own interests. They represented canning companies in Strathroy, Brighton, Waterford, Aylmer, Dunnville, Lakeport, Chatham, Picton, Simcoe and Delhi. They shared more than just their concerns for the industry. In this golden age of capitalism, they were members of a social class—entrepreneurs who had established their fortunes through shrewdness and enterprise.

32 After three days of talk these independent canners agreed to merge their interests to form a new firm called Canadian Consolidated Canning Companies Limited, a name shortened a year later to Canadian Canners Limited. It became, as its founding fathers had envisaged, the major force in the industry, exerting its considerable influence to keep down the prices paid to farmers and factory workers while maximizing profits. It even minted its own currency, distributing thin, aluminium tokens for every pail of tomatoes peeled by a factory worker.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 733 Whenever the opportunity arose, Canadian Canners enlarged to strengthen its hold on markets and production. In 1904, it brought the A.B. Saylor Company of Bloomfield for $10 000 in cash and another $10 000 in preferred stock. Two months later, the A. C. Miller Company of Picton sold out for almost $26 000, about one-third the price its owners had originally demanded. This was the pattern of acquisition that would characterize the company.

34 By 1906, Canadian Canners had 30 factories in operation throughout the southern portion of the province—almost half the total number of factories packing canned goods. As an early account indicates, the company had already made its presence felt:

35 The company also drove a hard bargain with its growers. Through the harsh terms of its canning contracts with farmers, it maintained low prices and dictated tough standards that had to be met. The company alone was the sole judge of quality and quantity of produce that local farmers hauled to its weigh scales. Farmers could protest but in the end, the factory's decision was final. "It was the way Canadian Canners were using the growers that got the farmers into the idea that they'd like to try it themselves."4

36 Many farmer-run canning co-operatives were established in the county. They were almost always successful too, generating substantial returns for their shareholders and freeing farmers from the harsh contracts of the existing companies. Unfortunately though, the co-operatives were often bought out by Canadian Canners and the independence they provided was short-lived.

37 In 1925, however, farmers in the Bloomfield area banded together to form yet another farmer-run factory, Hallowell Canners. While this co-operative operated only a few years before its purchase by a larger firm, its success prompted many of its shareholders, including former school teacher J. Ed Baxter, to become members of a new company founded in 1929— the Baxter Canning Company, a firm that would become one of the most successful in the area. At the peak of its production, Baxter Canning packed 500 000 to 600 000 beans annually and employed a summer staff of 200. It sold its produce to Loblaws, Dominion and A. and P. Stores and packed its own Silver Ribbon Brand produced for several decades until its sale in the 1970s.

38 There were still others who built their own factories, men like J. W. Hyatt of West Lake, Sylvester Church, the Greer Brothers of Wellington, Fred Folkard of Northport, J. S. Sprague and Ernie Johnston. Both Sprague and Johnston established telephone companies later integrated into the Bell telephone system. Fred Folkard was renowned as a near genius who could fix or invent almost anything. They were economic adventurers who gambled and won in the canning game, making "a go of it by working hard day and night."5

39 In 1912, James Carter, an apple grower from Waupoos, began a co-operative factory packing the peas, tomatoes and corn grown by the farmers of his area. The company he founded, the Waupoos Canning Company, continued to operate until the mid 1980s.

40 "This is where people had the imagination to get into the business," says Jay Hepburn, a former manager of the firm. "Mr. Carter developed one of the first pea processes which really did the job. He was recognized as packing the best peas in Canada at one time. He just experimented in his kitchen...and he finally developed a process for canning peas that required the minimum amount of time under pressure. Basically, it's the same process that's in use now."6

41 James Carter typified the ingenuity that characterized his company over the years. He was one of the first canners in the county to market tomato juice, a by-product of the tomato canning process that for many years was simply tossed into the nearest creek or bay. But the product was not an immediate success. Carter packed his juice in glass jars which grocers displayed in their front windows. Over a period of time, the bright red colour of the product faded in the sunlight and customers were reluctant to buy it. It wasn't until he began packing his tomato juice in tin cans that it met with consumer acceptance.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 842 In the early years of the industry it didn't take much money to get started in the tomato-canning business. The first operations washed, steamed, peeled, canned, cooked and cooled tomatoes just as canners do today, although the pioneers were considerably less efficient. They used huge kettles or "hog-dipping cauldrons" to soften the skins of the tomatoes so that they could be peeled more readily by the scores of women employed at this task. Next the vegetables were dropped whole into cans which were later sealed and heated. As the industry matured, freshness and cleanliness became the major considerations.

43 "My mother's by-word was always: 'Be sure and wash your hands every time you come in to do anything because cleanliness was one of the main things,'" recalls Audra Brickman of the Brickman Canning Company in Ameliasburg. "And put up good stuff. You can't can good stuff if you don't have good stuff to work with. We tried to do it fresh. We'd pick in the morning and can in the afternoon...It didn't sit around for a week or so before it was done."7

44 Fresh produce and sanitation became such fundamental axioms of the industry that Canadian Canners eventually adopted "Quality and Cleanliness" as the company's motto.

45 Peas and corn were the other major canning crops in Prince Edward County. Peas, in particular, are difficult to nurture and harvest. This vegetable likes cool nights and hot days with just enough rainfall to grow its lush vines and bursting pods. At first, the crop was harvested entirely by hand. Hundreds of labourers lived day and night in the fields during the season, picking the pods and then shelling them. It was a costly, time-consuming business, especially unsuited to a crop that can deteriorate from the top quality grades of fancy and choice to standard quality in just a few hours. The pioneer canners soon began to investigate alternative harvesting techniques and the invention of an efficient mechanical pea harvester proved to be one of the most significant technological advances within the industry.

46 A successful pea harvester was not developed until 1890 when a machine invented by the Chisholm Brothers of Oakville, Ontario and R. P. "Bob" Scott of Ohio passed a rigorous field trial in New York State. The Chisholm-Scott pea viner not only separated the pods from the vines, it also knocked the peas from their shells, eliminating the need for a large work force. A series of paddles struck the pods, compressing the air within, which in turn broke open the pods, releasing the peas amidst a cushion of air onto a conveyor belt.

47 The Chisholm-Scott pea harvester was sold extensively throughout Canada and the United States and the machine was a common sight for many years in Prince Edward County. Its invention would also have several other ramifications. Pea crops were now harvested on a single occasion as opposed to the old way, with fields hand-picked several times. Since individual plants mature at different intervals, this technological advance encouraged growers to become more knowledgeable about the soil and the climate demands of the crop. It also helped promote the development of better quality pea seed.

48 By the early 1880s, exporter John H. Allen of Picton had earned an international reputation for his high quality seed. While Allen sold much of his pea seed to English buyers, his major market was in the United States. Not far away in the village of Wellington, W. P. Niles ran a second seed enterprise.

49 Allen eventually sold his business to American interests, the Cleveland Seed Company of Cape Vincent, New York. But in 1905, the firm was once again in Canadian hands. The new owners, the Hogg and Lyttle Seed Company, were still heavily involved in the export of seed peas in 1930. In that year, the company employed a dozen men and 104 women to sort and bundle 2 500 to 3 000 bushels of seed peas each week, three-quarters of it for export.8

50 While John Allen, Bob Scott, the Chisholm Brothers and others tacked the problems which confronted growers in their fields, another group of men pondered the mysteries of food processing itself. The science of microbiology was in its infancy. Few of the pioneer canners had much knowledge of the chemical reactions at work in the manufacture of canned goods.

51 They believed creating a vacuum in tinned foods was the most important consideration. It was exposure to air, they believed, and not the work of organisms within the food that caused spoilage. Accordingly, they boiled their canned goods in hot water baths for several hours before opening a small hole in the lids to allow the air within to "vent" or escape before the can was re-sealed and subjected to additional heating.

52 A sound, properly processed canned product held no air. A can with a vacuum emitted a particular note when "tapped" or struck with a metal instrument. An inferior can produced a duller sound which skilled inspectors could readily detect. But despite these early processing techniques and efforts at quality control, many consumers opened cans that gave off a sour, disagreeable odour. Moreover, their contents were badly decomposed. What caused this spoilage? And why were some cans affected while others were not? It took several years of research before research scientists found the answer.

53 Experiments by researchers at the Massachussetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge showed that some bacterial spores could endure the heat of boiling water. The results encouraged canners to utilize steam "retorts"—commercial pressure cookers that generated much greater heat—to more effectively combat their persistent adversary.

54 Yet another problem facing the industry during these early years was the reaction which took place between food and the metal containers in which it was prepared or stored.

55 "They cooked in open kettles at that time," recalls Jay Hepburn, former manager of the Waupoos Canning Company. "Then they evolved into using brass and copper kettles. People weren't that particular at that point in time. Now it's all done under vacuum and stainless steel evaporators...Back then they couldn't detect the residual amounts of tin, copper or brass in the product."9

56 Traces of tin from the cans dissolved in the food and caused fruit syrup to become cloudy or to change from a bright red or purple colour to a mouldy blue. Black specks often appeared in canned corn, meats, fish, and other vegetables. But, surprisingly, few cases of food poisoning were reported in North America during this period, despite the inadequacies of early processing methods. From 1899 to 1921, there were only 345 cases of botulism reported in Canada and the United States and only a small proportion of these proved to be the result of delinquent canning techniques.10

57 Eventually, the industry discontinued the use of certain metals in the manufacture of cooking containers. Herbert A. Baker, a native of Oshawa and a soft-spoken chemist who worked for the American Can Company in Baltimore, hastened the development of a tin can lined with a special lacquer to prevent reactions between the food and its container. Baker demonstrated how hydrogen sulphide gas within food reacted with the metals used to make and seal cans to form the black specks which appeared in so many canned products. The discovery was so significant that Baker rose from the relative obscurity of his laboratory to become president of the company a few years later.

58 As a result of such inventiveness, the American Can Company became the dominant supplier of cans in both Canada and the United States. Following its purchase of a can manufacturing company in Hamilton in 1904, the company entered into a profitable partnership with the dozens of factories operating in Prince Edward County. A. A. Morden of Wellington and A. P. Hyatt of West Lake were two of the first canners in Canada to use the firm's new "sanitary can" introduced onto the market in 1905.

59 The canning industry in Prince Edward County prospered and grew. From 1920 until the late 1950s, about 35 factories operated continuously in the area and life during the summer months in this historic, rural community revolved around the blasts from the steam whistles which adorned the roof of every factory.

60 Despite advances in processing and harvesting methods, however, the canning industry remained a precarious way to make a living. "You were terribly dependent upon the weather," says Mrs. Connie Mowbray of Picton. "If tomatoes were put in and it was dry, why they'd shrivel up. We'd be bothered by black rot if we had a lot of rain...One year because of a glut [of tomatoes on the market] we had to plough acres and acres of beautiful tomatoes under because the factories wouldn't take them."11 Poor weather ruined crops. Ideal conditions resulted in bumper crops and decreased prices. These are the traditional laments of Canadian agriculture and the canning industry was not exempt. "Everybody had ulcers in that business."12

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 961 The war years were good ones for the canners of Prince Edward County with local factories operating at record capacity to meet the demand for food. Despite sugar rationing, a shortage of help and considerable bureaucratic red tape—it took the J. S. Sprague Factory at Mountain View a full year to received authorization to buy a cement mixer needed for improvements—about 40 Prince Edward County canneries produced 1.5 million cases of tomatoes alone in 1941, 43 per cent of the total tomato production in Canada.13

62 During the war, the Lome Brickman factory in Ameliasburg township devoted one day a week to the production of jam which was donated to the Canadian Red Cross. Most of the jam was distributed overseas to organizations caring for British war orphans, but some of it found its way on board a British vessel evacuating French prisoners of war from Russia. After years of uncertainty and deprivation, the Frenchmen considered the jam a treasured gift symbolizing their freedom.

63 While the canning industry of Prince Edward County was still a lucrative venture, these were changing times. The war years had also been profitable for the canning companies in the more favoured areas of southwestern Ontario. The company that Arthur Libby, his brother Charles and Archibald McNeill had started in a small building in Chicago in 1867, was now renovating the plant they had constructed in Chatham, Ontario, in 1917. Libby, McNeill and Libby soon purchased another plant nearby in the town of Wallaceburg as part of a massive modernization program.

64 Similarly, the H. J. Heinz Company built a new head office at its Leamington factory in 1948 and embarked on its own modernization program throughout the 1950s. Moreover, years of research by the company's Growers Service Department was starting to pay dividends. Company experts had succeeded in developing tomato varieties that more than doubled yields. Leamington became the ketchup capital of the world.

65 In contrast, few of the canning companies in Prince Edward County were adapting to the times. "I think quite frankly," say Jay Hepburn, the former manager of the Waupoos Canning Company, "the people that came out of the war years and the postwar years got pretty fat and pretty lazy in the business. They spent the money and when it came time to update the equipment and so on...they didn't do it. This, primarily, was the reason why so many plants closed."14

66 Hepburn's company was one of the few exceptions. Continuing the innovative tradition of its founder, James Carter, the first county canner to market tomato juice, Waupoos Canners embarked on a modernization programme, which dramatically reduced labour costs while increasing productivity. In 1943, the firm invested $10 000 on a vacuum evaporator to convert tomato waste such as peels, cores and under-sized tomatoes into tomato paste, a product becoming more popular with Canadians as a basic ingredient in sauces and other dishes.

67 They became the first in the county to use mobile pea viners—harvesters that could travel to the crop, eliminating the extra handling and shipping of the old system where pea vines were cut in the field, trucked to stationary viners, threshed, and then trucked again to the factories. The new equipment represented an extraordinary technological advance. With this single purchase, production at the Waupoos factory increased three times while staff was reduced from 125 to just 35 persons.

68 Later, Waupoos Canners began processing snap beans, a crop which matures between the pea and tomato business. By processing this crop, the factory ran at full capacity all summer long. Modernization and innovation—these were the company's recipes for survival in an age when many plants were forced to close. However, few other local factories were taking steps to adjust to the new realities of an extremely competitive marketplace.

69 Increasingly, the canning industry was becoming dominated by large corporations. H. J. Heinz, Libby, McNeill and Libby of Canada, Campbell Soups and Canadian Canners Limited were the largest canning operations. In 1956, the California Packing Company (CALPACK) announced a merger with Canadian Canners Limited, an amalgamation which made the U.S. firm the largest company of its kind in the world. Canadian Canners, since 1903 the dominant force in a region devoted to canning, had itself become an aging giant. By comparison with the newer plants of its U.S. patent, the company's factories were too old, too small and too inefficient. Within a few years, their plants in the area were all closed. The new owners preferred to destroy equipment rather than sell it to local canners.

70 "I tried to buy equipment from them when they shut down plants," said the late Ron Hyatt of the Hyatt Canning Company. "But they wouldn't sell it. They would deliberately smash it up before they would sell it to ya."15 With the purchase of Canadian Canners in 1956 by the California Packing Company, the domestic industry was firmly controlled by American multi-national corporations which often found it cheaper to use Canada as a dumping ground for excess production from their factories in the United States and elsewhere.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1071 CALPACK was buying a market—a market most profitably supplied by produce from its own U.S. subsidiaries. This was the fatal blow to the canning industry in Prince Edward County. By the early 1960s more and more of the fresh tomatoes Canadians ate were imported. By 1975, 56 per cent of the total Canadian market for canned tomatoes came from countries like the United States, Italy, Spain and Taiwan.16

72 Meanwhile, the markets for Canadian canned goods were becoming fewer and fewer. Chain stores like the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A. and P. Stores), Dominion, Loblaws and Steinbergs were beginning to assert their growing influence in the grocery trade.

73 National grocery chains became the principal buyers of canned goods in Prince Edward County and elsewhere. Because of their size and influence, these large, retail chains were able to control the market and exert considerable pressure on processors.

74 "The last number of years we were in business," says Don Walker of Cherry Valley Canners, "it got to the point where there were four or five big chain stores. If you didn't sell to one of them...you didn't have a market, that was all. They got to the point where they didn't ask you what you wanted for canned goods. They told you what the price of canned goods was and you took that price."17

75 First, the large retailers stopped buying canned goods in large quantities, preferring instead to purchase only enough stock to last them a week at a time. The canning companies, many of whom were already beginning to experience financial hardship, were forced to build heated warehouses and to borrow larger sums to defray expenses until last year's goods could be sold. At the same time, the chains began to have produce packed under their own labels in other countries where production costs were cheaper. For even the most patriotic shopper, it became harder and harder to "buy Canadian."

76 The work habits of Canadians were changing too. People no longer wanted the low-paying and physically-demanding seasonal jobs characteristic of the canning industry. It was hard, hot, dirty work, "I've known my husband to come home around two o'clock in the morning," recalls Dorothy Sayers of Picton, who started working at the A. C. Miller plant in 1922. "He wouldn't even go to bed. He'd have to be back at five o'clock. He'd just lay on the veranda and cool off...It was hard work, and not too much money."18

77 It wasn't only local residents who bent their backs in the summer heat. Migrant workers from northern Ontario emigrated to the county in such numbers they nearly doubled the population of small villages like Bloomfield. The factory owners built small, one-room "cottages" for them next to the plants. Some employees used their vacations from other jobs to add to the family income and visit local relatives.

78 "It was," says former canner Connie Mowbray, "the same people who brought their daughters and their daughters-in-law and they all worked. It meant they could pay for their coal during the winter and the school fees, or anything else they wanted."19

79 Women were always a major part of the work force. They laboured in the fields as pickers, or in the factories as peelers, standing on tired, aching feet hour after hour alongside a conveyor belt carrying a seemingly endless river of round, red tomatoes. Fifteen cents an hour was the average wage in the 1930s. Twenty-five cents an hour was big money. But such menial work became less attractive to Canadians over the decades. In Prince Edward County, men tried for jobs with the H. J. MacFarland Construction Company or at the Canadian Forces Base at Camp Picton. Their wives and daughters took jobs as clerks in local stores. Many others left to work in Toronto and other cities. The shortage of help became so severe, labour began to be imported from the Caribbean countries in the early 1970s.

80 "I don't anticipate we'll have one local tomato picker this year," says Walker who employed ten Jamaican workers in 1981. "Fifteen years ago, we'd have 25 [local] tomato pickers. There isn't anybody around who wants to do it. It's hard work...If they can't do anything else, they can always get some sort of welfare or unemployment insurance and that's a lot better than bending your back picking tomatoes."20

81 Finally, new legislation and regulations concerning pollution, worker safety and quality control, were adding to the costs of canning plants that were already only marginally profitable.

82 "Every time there was new legislation for this or that or something else," says Alex Williams, who operated Big Island Canners, "you reached the point where, Jesus, you wondered who you were working for...There wasn't any profit in it. You were working your ass off all the time and the price of tomatoes went all to hell."21

83 Williams sold his factory and quit the business forever in the 1960s devoting himself fully to his farm nearby, just one of many Prince Edward County canners to fall victim to the changing times. With each successive summer throughout the 1960s and 1970s, fewer canning companies operated locally. By 1985 only five factories were still operating. By 1990, only two remained—Cobi Foods of Bloomfield and Sprague Foods of Mountain View. These are the sole survivors of a turbulent era.

84 At Mountain View the Sprague Foods plant stands across from the factory J. S. Sprague built in 1925. Sprague's grandson, Roger, has abandoned attempts to compete with larger firms canning traditional crops like tomatoes and peas. His business now processes specialty products such as Mexican chick peas, red and white kidney beans and lentils— products popular with many ethnic groups in Canada.

85 Cobi Foods continue to operate a plant in Bloomfield, a small village that once bustled with the activity of several canning factories. Their factory is the former Baxter Canning Company, a firm founded in 1929 as part of the ground swell of discontent among local farmers against the monopolistic practices of the larger canning operations.

86 The canning trade today has little in common with the labour-intensive business that came to mean so much to Prince Edward County. From the field to the factory, modern canning is an ingenious mix of science and technology. The new varieties of tomatoes, as an example, are but distant cousins of the juicy, plump vegetables that were once the pride of Prince Edward growers. They are small, coreless and almost as hard as baseballs—ideally suited for the rigours of mechanical harvesting.

87 Tomatoes destined for supermarkets are picked green and mature in their packing cases during their voyages to distant destinations after applications of chemical ripening agents naturally found within the plants. Using these same chemicals, field tomatoes for processing can be encouraged to ripen uniformly so they may be harvested on a single occasion by huge mechanical "pickers."

88 The dynamic changes within this industry and others are bewildering to county men and women who spent a lifetime labouring in the canning business. But for better or worse, the long, hot days of the harvest season, familiar to so many local residents, have largely passed. Prince Edward County is no longer a significant force within the Canadian canning industry and with each succeeding summer, the business becomes less prominent within the local economics of the area. A generation of county residents has now started families without giving much consideration to the industry that once shaped the lives of their parents and grandparents.

89 Most of the old factories have been torn down; others lie idle and neglected, barely visible among the brush that now surrounds them. Sadly, there are fewer old timers each year to recall former times when Prince Edward County stocked the shelves of the nation with produce from its soils.

90 Still, there were some county residents, like Gerald McCaw of Glenora, who could recall those past days. In 1981, McCaw was nearly eighty years old and he lived alone in a graceful old farmhouse overlooking the waters of the Bay of Quinte. Inside, there were no pictures, news clippings or other mementos of the factory his father, Ed, built and ran for several years in Picton beginning around 1912. Yet, McCaw had a treasury of memories of that enterprise and others accumulated during a lifetime of farming and working in Prince Edward County.

91 "My God," he said, his weather-beaten face creasing in a hundred directions like a split cedar log, "there was a pile of factories around here them days."22

92 The decline of the canning industry in this small Ontario county is a reflection of the rapid technological and economic change that gripped North America after the end of World War Ⅱ. Modernization and volume production became the twin pillars of sound business practice. The small, obsolete factories of Prince Edward County were no match for the new processing plants constructed in southwestern Ontario, an area blessed with more fertile land and a longer growing season. As well, the tiny farms characteristic of Prince Edward County were not well suited to mechanical harvesters which operate most efficiently over large tracts of land.

93 The introduction of frozen food in the 1950s, the increased ownership of the industry by large multi-national corporations, the buying practices of national grocery chain stores, the introduction of new worker and health regulations and the changing work attitudes of Canadians all contributed to the eventual collapse of the industry that had meant everything to Prince Edward County.

94 Today, there are few traces of this bygone era in this rural Ontario community. The factories, if they still stand, now serve an ignominious and rusting retirement as warehouses or poultry farms. Prince Edward County has lost its title as the "Garden County of Canada."