Industrialization and Production / Industrialisation et production

Domestic Textile Production in Colonial Quebec, 1608-1840

Abstract

In the early twentieth century, ethnographers and economic historians showed an interest in a variety of themes including gender roles and the early evolution of textile production. Most work since then has been ethnographically and museologically based, drawing on historical sources, such as household inventories and marriage contracts but also on artifacts, a largely unknown phenomenon to most historians. While museum curators and specialists in Quebec ethnography have emphasized the material remains of household cloth and the various steps in its fabrication, most economic historians have been primarily interested in agricultural and industrial productivity. Colonial historians, for example, use information about wool, flax and hemp in their arguments concerning self-sufficiency and commercial agriculture and rarely explore the ways in which households were organized to meet their daily needs. These historians have, therefore, neglected the role of female labour in the countryside, as well as women's participation in the rural marketplace. Although woman's work and clothing are also within the sphere of social history, the lack of sources and the fact that these subjects are usually treated within larger contexts has meant that cloth making and use have yet to receive the attention they deserve. After surveying the historiography related to home-made textiles, the author discusses the role of the domestic production of fabric in Quebec, as well as the subject of gender in the making of household cloth.

Résumé

Au début du XXe siècle, les ethnographes et les historiens de l'économie se sont intéressés à une grande variété de thèmes, y compris les rôles sexuels et l'évolution de la production textile au début de la colonie. La plupart des travaux des dernières décennies s'inscrivent dans une démarche ethnographique etmuséologique, et reposent sur une documentation d'époque, comme des inventaires de ménages et des contrats de mariage, mais aussi sur des artefacts, une source largement inexploitée par la majorité des historiens. Tandis que les conservateurs de musées et les spécialistes de l'ethnographie québécoise ont mis l'accent sur les vestiges matériels des textiles domestiques et les diverses étapes de leur fabrication, la plupart des historiens de l'économie se sont surtout intéressés à la productivité agricole et industrielle. Les historiens de l'époque coloniale, par exemple, exploitent les données accessibles concernant la laine, le lin et le chanvre dans leurs exposés sur l'autosuf-fisance des premiers colons et l'agriculture commerciale, mais ils étudient rarement les modes d'organisation familiale qui permettaient aux ménages de subvenir à leurs besoins courants. Le rôle de la main-d'œuvre féminine à la campagne, de même que la participation des femmes à l'économie de marché en milieu rural, sont par conséquent des aspects que ces historiens ont négligés. Même si le travail des femmes et l'habillement ont leur place dans l'histoire sociale, l'absence de sources et le fait que l'on traite ordinairement de ces sujets dans des contextes plus larges ont malheureusement mis en veilleuse l'étude de la production et de l'utilisation des étoffes. Après un survol de l'historiographie consacrée aux textiles de fabrication domestique, l'auteur examine le rôle de la production familiale du tissu au Québec, ainsi que les aspects sexués de la fabrication d'étoffes pour la famille.

1 Quebec's agriculture is the subject of much historical investigation in Canada, but historians have written little about women's farming efforts. This is particularly true of the non-mechanized production of textiles, an important activity in rural Quebec which existed well into the twentieth century. Although historians have neglected the role of female labour in the countryside, as well as women's participation in the rural marketplace, ethnographers have examined the fabrication of household textiles by rural women. Whereas ethnographers emphasize traditional domestic activities and neglect periodization, historians tend to disregard the former while using the latter as a starting point for their work. In order to explore the existing literature on this subject and to identify the role of women in the domestic manufacture of fabric, I will review the pertinent historiography, describe the non-mechanized fabrication of cloth in the province, and discuss the importance of gender in the production of homemade textiles.

Historiography

2 The evolution of the historiography of Quebec textile production has been dominated by two distinct currents, ethnographic and economic. Only during the last two decades have social historians developed an interest in this field, concentrating most of their work on industrial labour relations, working conditions and gender roles in the factory (1850-1950). This is probably due both to a paucity of sources available for the colonial period and to the current interest among Canadian historians in the study of industrialization in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

Ethnographic and Museological Approaches

3 Clothing, especially that of certain groups, such as voyageurs and habitants, has long been the object of curiosity among artists and travellers describing early Quebec customs.1 Drawing on these iconographical and literary sources, a group of Quebec ethnographers, or ethno-historians, began during the early twentieth century to study the material traces of French culture in the province. Some, such as Pierre-Georges Roy, emphasized documentary sources while others, like E.-Z. Massicotte, also explored folklore and ethnographic traditions. Their combined research has provided a basis for what is today identified as the ethnology of French America, which defines its field of study as the traditional civilization of Quebec.2 These scholars have written more about household textile production and use than their colleagues in other disciplines.

4 Early ethno-historians, such as Roy, Massicotte and Marius Barbeau, used information contained in interviews, census returns, correspondence and notarial records to gather information relating to tools and clothing, thereby forming the basis for their understanding. Although few of these studies used broad social or economic approaches or were systematic in their use of sources, the authors' observations and conclusions remain pertinent. For example, Massicotte questioned the relationship between locally-produced and imported cloth and identified gender roles and regional variations in consumer practices and textile production.3 For the most part, however, because early-twentieth century ethnographers knew they were writing about the disappearance of traditional domestic crafts, especially hand-carding, spinning and weaving, they were particularly concerned about describing the various stages and activities involved in the home production of cloth.4 They tend, therefore, to be more descriptive in their writing than analytical.

5 One of Quebec's best-known heirs to the early ethnographic tradition was Robert-Lionel Séguin, whose 1967 and 1968 monographs on the traditions of farming families and clothing are now considered classics in their field. Séguin used a wide range of sources, including artifacts.5 Although his treatment of the habitant has been criticized by historians for being too static, Séguin's work has had a lasting effect on ethnographic and museological studies.6

6 His monographs were among the major sources used in another influential work on this subject written by Harold and Dorothy Burnham of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto and published in 1972. The Burnhams wrote a number of pioneering works in this field and developed a museological approach to textile history. Their artifact catalogues begin with a brief historical introduction, followed by a selection of products and equipment found in different museum collections.7

7 With the exception of social historians, who often refer briefly to clothing, the field of Quebec's clothing history has been treated mainly by specialists in ethnography and museum curators.8 Because of the traditional way museum collections have been organized, curators have tended to specialize either in textiles, like the Burnhams, or in clothing, thus isolating two inseparable subjects. While another ROM curator, Katherine Brett, was beginning to build a substantial clothing collection, as well as publishing articles on the subject, a well known Quebec ethnographer, Madeleine Doyon-Ferland, was making an important contribution to the popularization of traditional clothing.9 Yet another museum curator, Jacqueline Beaudoin-Ross of the McCord Museum in Montreal, has analyzed evidence of rural female dress in Quebec found in travel literature, a wide range of iconographical sources and artifacts.10 One of the more detailed studies of rural clothing is Bernard Audet's analysis of post-mortem inventories from the île d'Orléans between 1670 and 1710. Following in the Séguin tradition, Audet provides a description of clothing items found in the inventories.11

8 Despite the interest in new ethnographic approaches, such as the concern for social attitudes and values, most recent students of clothing and textiles continue to develop themes relating to the adaptation to the environment and changing styles and appearances. Publications written in the 1970s and early 1980s explore in greater detail topics only broached by Séguin, but most of them appear to be influenced not only by the themes developed by him, but also by his use of interviews, inventories and artifacts.12

9 Edited by Jocelyne Mathieu in 1988, one of the most recent studies of costume history appeared in a special issue of Canadian Folklore canadien. Although qualitative approaches and the ethnographic emphasis on the non-temporal nature of traditional rural clothing are very much in evidence in this collection of essays, other subjects, such as the evolution of communications, technology and mentalités are also mentioned. The clothing of specific groups is treated in detail, as is the hooded coat. In addition, some authors use quantified data, and refer to the availability of imported products. The impact of this material on homemade cloth and the relationship between the raw resources of textiles and the finished products, receive less attention. A more comprehensive study of existing references in social and economic history would have provided some of the review's ethno-graphic and museological analyses with a stronger contextual framework and a better understanding of the representative nature of items discussed. Despite these shortcomings, the authors' use of sources and statistical data, plus their treatment of ethnic and social influences, make this well illustrated volume an indispensable guide for students of Quebec clothing history.13

10 The ethnographic contribution to the evolution of Quebec textiles has been substantial, but its frequent reliance on anecdotal sources suggests additional work would help establish the relationship between clothing and textile histories, as well as provide necessary syntheses of these inseparable subjects. It would be informative to identify and analyze the underlying presuppositions and biases of earlier writers, such as Madeleine Doyon-Ferland, and to verify their conclusions. This is particularly true in two areas, the rapport between imported and domestic products and the roles men and women played in textile production in the home and in the mill. These subjects will be treated further after consideration of how economic historians have studied textile history.

Social and Economic History of Textile Production

11 While Museum curators and specialists in Quebec ethnography have described the material remains of household cloth and the various steps in its fabrication, most economic historians have been primarily interested in agricultural and industrial productivity. Related subjects, such as domestic production of textiles and the isolated attempts to market them locally, have received little attention.14

12 In addition to studying farming techniques and crop statistics, historians who have touched on Quebec's textile history have been preoccupied with issues relating to colonial manufacturing and the growth of textile plants in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Early aspects which have been studied include the importation of fabric from overseas, the absence of colonial cloth-making establishments, and the initial attempts to create them.15

13 Historians of colonial agriculture have also emphasized the subject of productivity. They used information about wool, flax and hemp in their arguments concerning self-sufficiency and commercial agriculture, but rarely explored the ways in which households were organized to meet their daily needs. Quebec historians have long been interested in the family economy, but since this subject has been treated only as a part of agricultural history, it has not yet been developed in detail.16 Although a few recent analyses of Quebec agriculture have mentioned domestic textile production and tools for making household cloth, most historians, while examining the raw materials needed for the fabrication of textiles, neglect the processes and results of domestic transformation.17

14 Social historians have shown an interest in clothing, but since the subject has been mainly treated as one aspect of daily life, the amount of information about it tends to be sparse.18 Thus, little has been written about such socio-cultural subjects as the symbolic significance of clothing for different ethnic and social groups.19

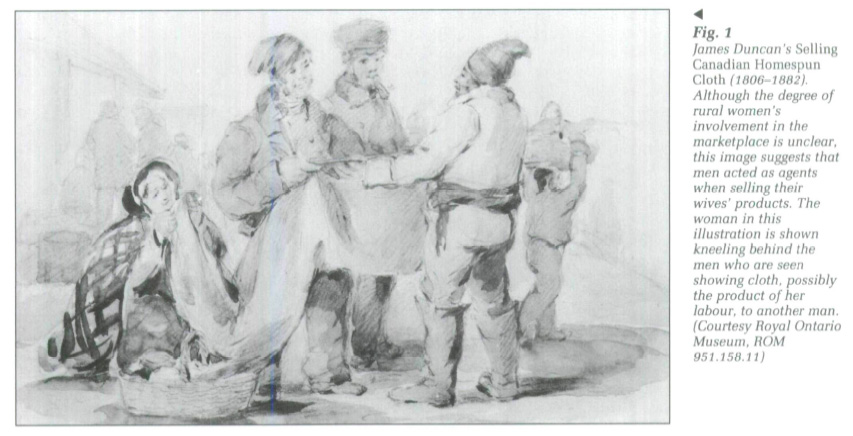

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 115 Although there are a few exceptions to the rule, notably in the monographs of ethnographers and ethno-historians, such as Robert-Lionel Séguin and Jean Provencher, most of these scholars tend to ignore the results of each others' work.20 Indeed, in the realm of the daily activities of rural women, most economic historians appear unaware of the ethno-graphical literature about domestic female labour and add little to the work of their colleagues in ethnography.21 Moreover, despite the amount of material published on different facets of textile history, no one has set out a simple chronology of mill evolution or analyzed the relationship between household and industrial textile production. Various pertinent questions have yet to be answered: When and where did the first mills develop? What materials did they use? What types of goods were produced? And, what impact did they have on styles and on the making of homemade fabrics?

16 The deficiency in sources mentioned earlier is particularly evident in the field of colonial textile history. Although early census returns mention weavers, they are absent from this source between the late-seventeenth century and the mid-nineteenth century.22 Thus, one has to look to other anecdotal sources, such as government correspondence and newspapers, to find additional information. In a study of newspapers, only a few references to textile establishments were found, notably in the Montreal area and Eastern Townships between 1796 and 1832.23 Although this information may lead to additional research, it hardly compares to the wealth of data that exists on early textile mills in the United States and overseas.

Homemade Cloth in Quebec, Ontario and the United States

17 An avenue worth exploring is a comparison of the non-mechanized fabrication of American and Canadian textiles. Working with data which is not always comparable, I analyzed hand production in the United States and Upper and Lower Canada in the early nineteenth century and found that whereas farming families in the United States made ten yards per inhabitant in 1810,24 Lower Canadian families produced 8.3 yards per person in 1827, falling thereafter to 3.2 yards in 1842 and 2.7 in 1851. Although American figures for later periods are unavailable, it is interesting to note that, while the Lower Canadian output was dropping in the third and fourth decades of the nineteenth century, it remained much higher than that of Upper Canada. Lower Canadian families continued to make linen when American and Upper Canadian farming families were abandoning this time-consuming practice. In 1851 only 14,700 yards of linen were made in Ontario compared to over 900,000 in Quebec. While the Ontario figures continued to decline between 1851 and 1870, Quebec production rose by over fifty per cent. By 1870, Quebec farming families were producing four times the amount of cloth made by their Ontario counterparts, a trend which continued into the twentieth century.25 The continuation of the fabrication of homemade linen, combined with the extensive use of recycled and unusual materials, such as cow hair and the patching of cloth evidenced in artifactual analysis, all suggest that hand production in Quebec remained an important part of the farming family's economic survival.26 What kind of strategy did this type of activity represent? Was it subsistence agriculture? Were farming families finding it difficult to get involved in the larger market place, or were they increasing household production because they did not possess the necessary funds to acquired manufactured goods? Was rural Quebec becoming entrenched in an increasingly self-sufficient existence?

18 Although existing information provides some clues to these queries, more work is needed before we can begin to respond to many of them. For example, the amount of imported clothing in household inventories is an indication that rural families acquired goods at the market. What remains difficult to ascertain is the degree to which inhabitants were involved in the market and the nature of the material acquired there. Were they involved, for example, in buying and selling second-hand clothing? Despite the presence of Sunday clothing, the amount of homemade material in rural houses and its often dilapidated condition suggests rural women could not afford to be as concerned as their urban counterparts with appearances.27

19 This preliminary investigation of domestic textile fabrication raises a number of related questions. Were rural parents continuing to use expanding families as cheap labour to produce homespun? If the diminishing number of carding tools found in household inventories can be taken as a valid indicator, then it seems evident that women were taking raw materials formerly processed in the home to carding mills that were springing up around the province. This suggests that rural women were not opposed to time-saving solutions and took advantage of them when it was feasible to do so. In order to throw light on some of these questions, it is necessary to explore the degree to which household production met the clothing needs of the rural family and to identify clearly the workers at all stages of cloth production.

Homemade versus Imported Cloth

20 The idea that rural families made all of their clothing is frequently found in historical references, especially in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.28 Historians writing during the first part of the twentieth century have occasionally made use of these references, giving credence to the idea that the domestic fabrication of cloth was a widespread and traditional part of country life.29 This view was, moreover, also developed by early ethnographers who were among the first to describe the various stages involved in the fabrication of domestic cloth. When one realizes that the amount of homemade fabric continued to rise during the latter part of the nineteenth century, the relationship between pioneer ethnographers and their subject becomes clearer. Scholars were likely portraying household activities still pursued during their lifetimes. Some specialists may have assumed that they were describing vanishing techniques which had continued to exist unchanged since the early years of settlement. In fact, as shown below, the household fabrication of cloth did not become important until the early-nineteenth century.

21 Other chroniclers, like Séguin and the Burnhams, have been more precise in their descriptions of the evolution of household production but, like current specialists in ethnography, they appear to have overemphasized the quantities made.30 This is not surprising because, as mentioned earlier, the idea that farming families made most of their own clothing has been current in historiography.

22 In a 1983 article I demonstrated that, although the existence of domestic textile equipment was increasing in the nineteenth century, imported goods were far more important than previously thought. Based on 400 post mortem inventories, this analysis showed that while approximately forty-two to forty-six per cent of rural residents residing in the Quebec City area between 1790 and 1835 possessed enough equipment to produce cloth, over fifty per cent of important clothing articles were of imported material. Not only does this conclusion raise questions about the nature and evolution of household production in rural Quebec, it has implications for artifact-related studies, museum collections and exhibits: care must be taken not to confuse local production with textiles imported from Europe or the United States.

Gender in Textile Production

23 Who produced the household linen and clothing worn by rural inhabitants and what were the critical periods in the development of the domestic fabrication of textiles? For example, were the colonial producers itinerant weavers who used the raw resources from local farms to supply their residents with clothing? What role did women play in meeting the clothing needs of the family?

24 Answers for some of these questions are found in existing studies, but it is only through the analysis of a variety of sources, including artifacts and extant technology, that one can paint a more complete picture of the changing role of gender as a factor in textile production. The Burnhams agree with Séguin that, although trained craftsmen were rare in the French colony, men were the principal weavers well into the eighteenth century. While little is known about the activities of these artisans, most appear to have settled in villages and urban centres, especially in the Montreal area.31 In 1714, twenty-five looms existed in Montreal and rural families in neighbouring areas were having fabric made by urban weavers.32 When did female weavers begin making a significant quantity of homemade textiles? The Burnhams maintain that weaving gradually became a woman's occupation, and after a serious economic recession in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, rural women became responsible for spinning and weaving.33 What is important here is the Burnhams' identification of a significant change from male to female weavers occurring after 1825.

25 Is it possible to define more precisely when this change took place? Little weaving appears to have been accomplished by either men or women during the French regime, but women were said to be involved in this craft as early as the late seventeenth century.34 According to contemporary accounts and analyses of household inventories, women's role in spinning and weaving varied from region to region and gradually grew over the eighteenth century. Most women arriving in New France were too poor and too involved with household chores and child-rearing to have the means or time to weave. Women living on farms on the Ile d'Orléans in the late seventeenth century possessed a paucity of clothing, most of which was probably imported, and no looms.35 A hundred years later, their neighbours in the Quebec City area were equipped. An analysis of household inventories revealed that thirty-one per cent of farming families in the 1790s owned looms. During a slightly earlier period, between 1778 and 1782, in the less populated area of Saint-Hyacinthe, only four per cent of household inventories included looms.36 By the second decade of the nineteenth century, the percentage of looms in the Quebec City area had reached forty-seven! Thus, during the latter eighteenth century, a greater percentage of women in the settled areas of the province were weaving than their ancestors in less populated regions.

26 Women in recently settled areas such as Saint-Hyacinthe were, however, actively involved in spinning. During the 1780s over seventy per cent of households in the area possessed spinning wheels. This figure compares well with those for the rural areas neighbouring with Quebec City (sixty-three per cent) and Montreal (eighty-two per cent) in the 1790s . Women's activities obviously varied according to the nature of their families and farms. Young mothers could spin and look after children, but they could not spin and weave and take care of a family.37 Children who were old enough to spin thread and look after younger family members would have provided their mothers with enough support to allow them to weave.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 227 Between 1750 and 1835, the most significant increase in the availability of looms occurred between 1795 and 1807. In 1830 the Surveyor-General of Lower Canada maintained that weaving was the universal responsibility of the female members of the rural family.38 By this time the settlements along the Saint Lawrence River were more populated than earlier, and many of them included families of five or six children.39 Thus, a female labour force was available to undertake domestic tasks such as sewing, spinning and weaving. It was, therefore, at the turn of the century that women began to play a significant role in the fabrication of cloth.

28 What were the critical periods for domestic cloth production between 1835 and 1900? As mentioned above, the quantity of homemade fabric increased during the latter-nineteenth century. Some rural women were making more of their own cloth during the same time that others were finding employment in the growing number of industrial textile plants in Quebec. What, then, was the relationship between home and mill production in different regions across the province? Was the experience possessed by women and children in domestic sewing, spinning and/or weaving transferred to the early textile mills? It is necessary to recall that by 1871 seventy-five per cent of the workforce in the Canadian clothing industry was female. One wonders if the sexual division of labour found in the home was reproduced in the mills? This is an area where yet more work is needed.

Conclusion

29 In the early twentieth century ethnographers and socio-economic historians studied a variety of themes such as gender roles and the early evolution of textile production. Most work since then has been done by ethnographers who have drawn on historical sources, such as household inventories and marriage contracts. The debate animated in the 1960s and 1970s by Fernand Ouellet, Gilles Paquet and Jean-Pierre Wallot concerning an early nineteenth century crisis in Lower Canada's agriculture has been pursued by economic historians, some of whom have used farming aspects related to the fabrication of homemade cloth to support their conclusions. Some facets of Quebec's colonial textile history have been sketched by specialists in ethnography but most questions in Canada's early textile history, especially those concerning gender and household production, remain unanswered. More quantitative data has to be marshalled and analyses of different periods in the evolution of hand and mill production multiplied before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

30 Historians would benefit from a greater awareness of the work on traditional lifestyles by their counterparts in ethnography. For example, detailed historical reconstitutions of the colonial work day of rural women could be enriched by information from studies in Quebec ethnography of the sexual division of labour in the hand production of textiles in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Ethnographers and museum curators would be well served by current quantitative techniques and by the integration in their studies of existing data in economic history related to imports, and farm crops and animals.

31 In their attempt to build an integrated analysis historians can afford to include artifact analysis and the results of ethno-graphical field work. There are serious difficulties inherent in using these sources, but in some cases they are more informative than documentary ones. To quote the French historian Michel Vovelle,

The challenge is not only to explore new sources but to build multi-disciplinary teams capable of complementary and comparative work in the field of textile history. Although new research is needed, enough information already exists to form a basis for a unified approach to the study of Quebec's clothing and textile history.

* The author wishes to thank Adrienne Hood, Stanley Bréhaut Ryerson and Luce Vermette for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper.