Articles

The Gothic Revival and the Victorian Church in New Brunswick:

Toward a Strategy for Material Culture Research

Abstract

This article probes the relationship between ideas and objects in the context of nineteenth century worship. The artifacts of the Victorian church serve to inform this discussion of New Brunswick's Gothic Revival. Written from the perspective of a practicing historian, the article outlines a particular approach to artifact studies and offers a series of personal reflections on the significance of artifacts as primary sources. An artifact-studies methodology involving two complementary levels of object analysis is described and illustrated. Finally, consideration is given to the implications of the historical method in relation to the emerging interdisciplinary field of material culture studies.

Résumé

Dans cet article, l'auteur étudie les rapports existant entre idées et objets dans le contexte du culte religieux au XIXe siècle. Les objets de l'église victorienne servent à illustrer cet examen du renouveau gothique au Nouveau-Brunswick. Écrit dans l'optique d'un historien de métier, cet article présente les grandes lignes d'une démarche particulière proposée pour l'étude d'objets ouvrés et une série de réflexions personnelles sur l'importance de ces objets et tant que sources primaires. L'auteur décrit et illustre une méthodologie des études d'objets ouvrés comportant deux niveaux complémentaires d'analyse. Il examine enfin les implications de la méthode historique pour le nouveau secteur interdisciplinaire que constituent les études de la culture matérielle.

1 The Gothic Revival has been called Canada's national style.1 The years of sustained growth leading to Confederation and the gradual development of a national consciousness were the years that coincided with the Gothic Revival. Perhaps its most remarkable characteristic was the intensity with which ideas and objects came together to capture the Victorian imagination. This article explores the linkages between certain ideas and certain objects. It sets out some thoughts on the historical method in relation to the emerging inter-disciplinary field of material culture studies. While various disciplines have ably utilized physical evidence for some time, historians have tended to ignore artifacts. Accordingly, written from the perspective of a practicing historian, this article outlines a particular approach to artifact studies that has emerged out of a recent work on New Brunswick's Gothic Revival.2 It presents a research strategy specifically designed to integrate both verbal and nonverbal sources. Finally, it offers a series of reflections on material culture research in an effort to share personal impressions and insights gleaned in the course of this work.

Background

2 The Gothic Revival was at once an art form and a belief system. This duality determined that Neo-Gothic architecture would achieve its greatest expression in and through the church. Indeed, it was in the act of worship that many Victorians were first exposed to a distinctive Gothic setting. In these circumstances the bond between church and society underwent a kind of three-dimensional synthesis. This interaction between religion and culture was decisive. Both in England and throughout the English speaking world, perceptions began to change about the church and its mission and thus, about the meaning of worship. It was a complex, subtle process affecting people in different ways. Yet this dynamic relationship between the sacred and the secular had a particular point of contact for Victorians. The common ground can be found in the idea of revival; not necessarily in the evangelistic sense of the term, but in a comprehensive and creative rediscovery of ancient antecedents. This impulse to return to the past for inspiration and direction assumed many forms. It has been variously labelled as Tractarianism, the Oxford Movement, the Anglo-Catholic Revival, Ecclesiology or Romanticism. Through it all, however, it was the lofty spires and the stained glass, the stone tracery and the vaulted arch, the dimly lit sanctuary and the elevated altar that demonstrated the compelling power of a cultural revival; that served as the most characteristic expression of the Victorian curiosity with the Middle Ages.

3 In England and around the world, the concepts and contours of the Gothic Revival were most forcibly expressed in and through the Anglican church. By 1850, Anglican Christianity was increasingly identified with British cultural values. Particularly in the colonies, Anglicanism became something of a crucible where the religious beliefs and cultural values held by the faithful were crystalized through the liturgy of the church. The unmistakable profile of a Gothic cathedral meant the certain presence of a missionary bishop. Consequently, the combination of a revival in church building, together with the Tractarian movement's efforts to revitalize Anglicanism itself, saw Neo-Gothic values being proclaimed from the pulpit, through the sacraments and via the architectural fabric of the church. In British North America, this proclamation of Neo-Gothic values was played out in the context of Anglican churches more than in any other type of building, sacred or secular.3

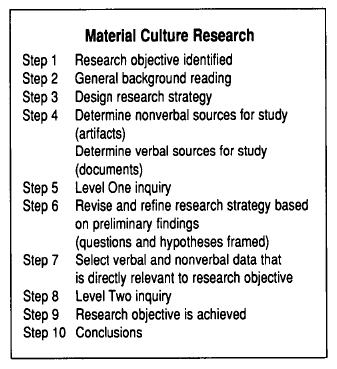

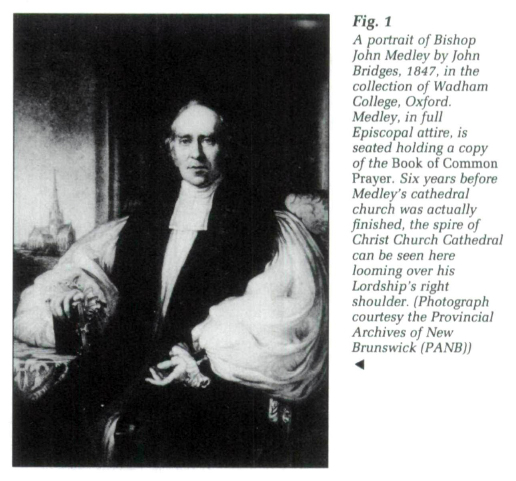

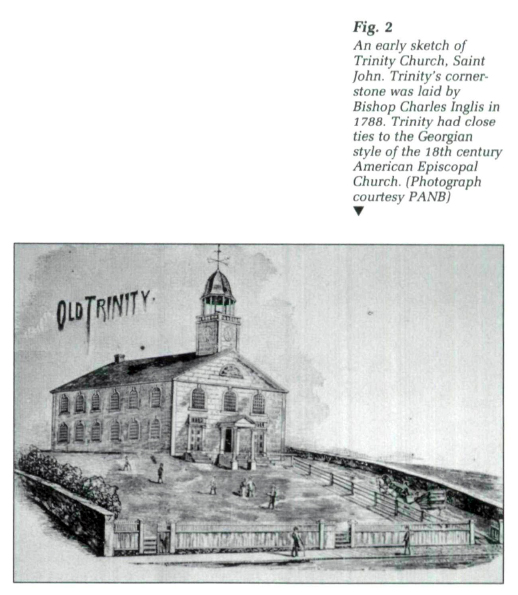

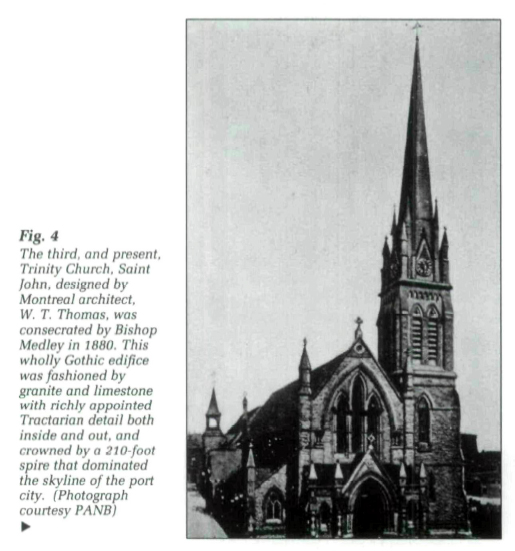

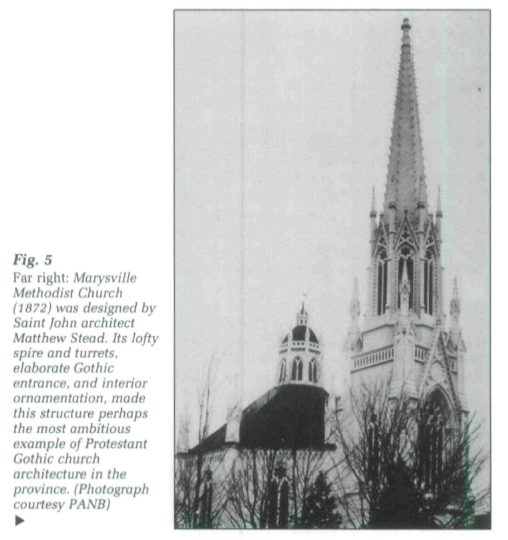

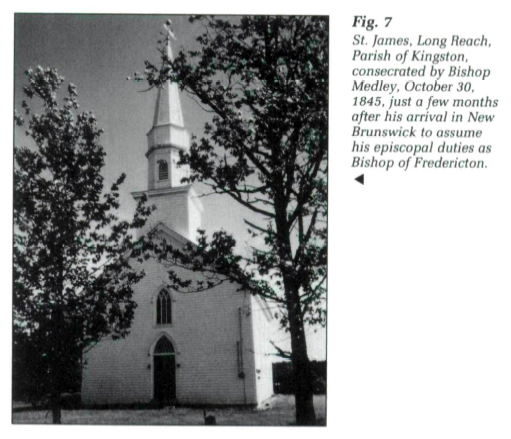

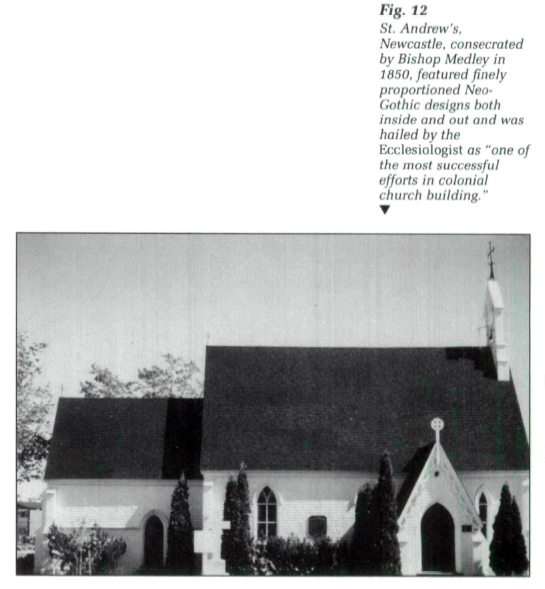

4 British church historian Owen Chadwick has pointed to the inherent difficulty of charting the influence of religious ideas upon an individual or a community, noting that this is a research task where "we need more local studies of religious development."4 Accordingly, this study assumed the format of a case study of the Anglican community in one colonial diocese. New Brunswick, as a relatively self-contained society during this period, serves as a convenient case in point for measuring the impact of the Gothic Revival on a particular group of people. The province's first Anglican Bishop, John Medley, arrived in Fredericton in 1845 with a well-defined Gothic vision for his Church. The ideas Medley brought to British North America were very current and very controversial. His episcopal career is important in the context of Canadian history, for among the missionary bishops, John Medley was the first prominent ecclesiologist to assume a colonial see.5 With a single-minded sense of purpose, Medley resolutely transferred the Gothic creed from Oxford and Cambridge to the communities and countryside of his new diocese.6 His particular contribution was to transplant and adapt his Gothic vision to one small portion of the colonial mission field. The three successive versions of Trinity Church, Saint John, serve to illustrate the transition Medley effected in ecclesiastical architecture, from Colonial Georgian to Neo-Gothic, during the course of the nineteenth century. The Church of England was clearly the object of his efforts, but judging from New Brunswickers' almost universal shift to Gothic forms during the third quarter of the century, Medley's efforts to introduce certain architectural precepts had some considerable impact beyond the province's Anglican community. By the turn of the century there was not a main street in New Brunswick untouched by the Gothic Revival.7 In this British colony as elsewhere, the Anglican bishop effectively transplanted something of the mother country into the local community. And so in New Brunswick, Medley's unrelenting Neo-Gothic programme was made manifest and came to personify England's faith, England's culture and England's empire. Here, in this juxtaposition of loyalties—to religious values, to cultural sentiments and to an imperial ideal—does one find the key to a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the Gothic Revival in New Brunswick history. Indeed, after 1845, New Brunswick became a proving ground for a significant chapter in Canadian architectural and religious history.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 55 At the heart of this study is a fascination with the Christian imagination. It was, and is, a way of seeing—other people, events, the material world, life in general, and, of course, God. A deeply creative faculty, the Christian imagination can be influenced, even inspired, by symbols. The faithful may differ over details, but all Christians attach importance to symbols. Perhaps a man will lower his voice in church, or a woman will refuse to wear makeup; someone will decide whether or not to wear a crucifix, whether to bow one's head to say grace, or genuflect at the holy name, or fold the hands, to stand, sit or kneel during prayer. Christian piety and worship is animated with symbolism of either gesture or objects or both. One discerns the unseen in the seen. One partakes of the bread and the wine, the baptismal water is consecrated, there is candlelight, sacred song and musical harmonies, there is holy symmetry in the images, decoration and design of the church building and its furnishings. The faithful employ the material culture of worship to come closer to the Divine Mystery because the surface of material things point to and proclaim the reality of the Spirit. One's approach to God, since it cannot be direct, must be assisted and characterized by symbols. Accordingly, the Christian imagination helped determine the form and substance of nineteenth century life. The Gothic Revival was a direct product of that imagination. To understand Neo-Gothic symbolism, to appreciate the metaphorical nature of Neo-Gothic aesthetics, one must be willing to fathom the phenomenon of Christian worship.

Methodology

I

6 The historian's task is to ask questions. The quest has to do with actuality in the past. The challenge is to devise ways to answer certain questions and then make judgements about the personalities and patterns of history. The investigative process is governed by various scholarly canons designed to protect the integrity of the work. Although there is virtually no limit to the kinds of questions which historians may ask, the significance of the answers is certainly related to the quality and availability of evidence. Occasionally, depending on the nature of the topic being studied, there can be great variety in the documentary sources considered, sometimes even types of evidence that extend beyond the conventional categories of written or printed documents. Such was the case in my study of New Brunswick's Gothic Revival. Thankfully, the discipline of history continues to encourage innovation and experimentation in pursuit of a more full understanding of the past.

7 This study rested on the integration of both verbal and non-verbal sources. The time spent searching out manuscript and secondary references in archives and libraries was equalled by time in the field, cataloguing churches and ecclesiastical furnishings. The completed work represents something of a new departure, methodologically speaking, within Canadian historiography. It reflects the historian's growing fascination with arti-factual evidence.8

8 The flurry of intellectual interest in the artifact which has characterized a growing body of North American scholars over the past two decades belies the fact that material culture studies remain an underdeveloped branch of humanistic enquiry. Employing Leslie A. White's three main subdivisions of culture—material, social and mental—it is clear that the theoretical and methodological parameters of material culture have been addressed less frequently than the other two.9 On the other hand, the growing interest in the scholarly potential of the artifact is not without precedent. It is instructive to place artifact studies in their historical context.

9 The first systematic study of non-literary evidence is usually identified with a branch of European scholarship of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries labelled the Age of Antiquaries.10 The particular legacy of the antiquarian movement to historical scholarship in general is in the area of methodology.11 The English Society of Antiquaries was founded in 1707, and it identified its interests as "Ancient Coins, books, sepulchres or other Remains of ancient Workmanship..."12 The distant origins of antiquarian studies need not concern us here, rather we want to understand how the study of objects transformed the historical method during the eighteenth century, so much so that by 1800, the debate between antiquarians and the more theoretically-minded historians had become more of a dialogue.13 By this time the factual, object-orientated knowledge of the antiquarian investigator and the philosophic imagination of the historian were seen as being compatible.

10 The work of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) typifies this emerging pattern. Referring to his History of the Decline and Fall of the Rowan Empire, Gibbon commented that, "...it is seldom that the antiquarian and the philosopher are so happily blended."14 Gibbon's methodological synthesis has been assessed by the Italian historian, Arnaldo Momigliano in this way:

11 The new quality that emerged out of Gibbon's work was a more balanced synthesis of literary and non-literary sources, a more full integration of the two, based on methodical study and creative insight. Contemporary students of history would do well to acknowledge and adapt the implications of such an approach. Traditional historians might dismiss such an endeavour as being a "multi-disciplinary" study. Perhaps they should look again. Certainly the study of history has matured considerably over the past two centuries. Nevertheless, many of the questions Gibbon and his colleagues were posing with respect to the selection and integration of diverse kinds of evidence deserve our continued attention. On the one hand there is the antiquarian's preoccupation with the characteristics of the historical object— artifacts are measured, counted, sorted, listed, categorized, and described with great precision. On the other hand, there is the historian's commitment to understanding change in the past, a fascination with people, patterns and perspective in history. Gibbon glimpsed the scholarly significance of an amalgamation of these two kinds of enquiry. This continues to be the promise of the emerging field of material culture studies.

12 But how is the artifact to be interpreted? How does one proceed to unlock its secrets? Obviously the historical object has little utility if it remains mute to the modern scholar. Can the artifact's testimony be translated into terms acceptable to the historian? This matter was alluded to by R. G. Collingwood in his influential 1946 book, The Idea of History. Here Collingwood helped to clarify the intuitive nature of historical knowledge by outlining his views on history as the re-enactment of past experience. In an entirely subjective and vicarious manner, the investigator must attempt to re-experience the past in his own mind.16 This procedure can be of considerable value if the researcher possesses extensive background information with which to ask relevant questions and make appropriate judgements. Combined with this sensitivity to historical context, according to Collingwood, is the necessity of employing a broad range of historical evidence. Speaking of non-literary sources, he asserted, "The enlargement of historical knowledge comes about mainly through finding how to use as evidence this or that kind of perceived fact which historians have hitherto thought useless to them."17

13 Artifacts are facts—in three dimensions. In recognition of this, Collingwood went on to discuss the possibility of re-experiencing the past, in part, through objects. Acknowledging the inherent subjectivity of this process, he held that it was at the very heart of the historical enterprise. Artifact studies, like history itself, grasp meaning through intuition. Yet it is this intuitive aspect of artifact studies that has led to much suspicion among some members of the historical fraternity. The charge has been made that artifact analysis lacks the requisite scholarly rigour, that it lacks precision, that it is based on hunches and opinions and is not open to independent evaluation.18 I submit that such a position betrays a misunderstanding of intuition as a mode of scholarly enquiry. Often, the most important kinds of humanistic knowledge are intuitive. This kind of knowledge cannot be proven, only described in the form of examples. As Jacques Barzun has noted, "The historian in general can only show, not prove; persuade, not convince; and the cultural historian more than any other occupies that characteristic position."19

14 More recently, Jules Prown has written about the nature of the interaction between investigator and artifact. Speaking of stylistic analysis of historical objects, Prown says,

Borrowing from phenomenology, Prown seizes upon and develops the most important aspect of material culture research—the direct and immediate power of the object to impress itself upon the intellect and the emotions of the individual, then and now. This characteristic of objects is constant over time. Through an interactive process between object and individual, basic attitudes, values and beliefs in the past are understood not in quantitative terms of frequency, duration, or distribution; not necessarily in terms of neatly measurable economic or demographic or political variables, but instead, in qualitative, affective terms.21 There is the sense in which material culture studies are to the discipline of history what phenomenology is to philosophy. A balance is arrived at between the meaning of ideas and the meaning of things, between analysis and observation, between interpretation and description.

15 A direct encounter with the artifact(s) will, therefore, maximize the research potential of the material evidence under investigation. This is not always possible, as in those situations where buildings or objects of interest have not survived, and resort must be made to secondary descriptions or accounts of the material environment. Still, the most fruitful kind of material culture research consists of those instances where the investigator personally scrutinizes the artifacts.

II

16 At an earlier stage in my work I was of the opinion that it was possible to devise a model for material culture research which would have wide application beyond the disciplinary and topical bounds of this study.22 I now see this view as naive and have lowered my expectations somewhat. Though designed to be repeatable in the context of my particular topic, the wider utility of the following research method is problematical at best. Perhaps its value for practicing historians lies in the fact that it represents an honest effort to sift the testimony of material evidence and to discern the meaning of this evidence in relation to a specific set of questions.

17 In seeking to identify and define my subject, I asked what it was that I wanted to explore and why? My long-standing interest in Canadian cultural history served as a general frame of reference. There was, as well, a fascination with questions of religion in history; of the influence of the church on both the public and private spheres. I had always found the interplay of the secular and the sacred to be a particularly compelling theme. Thus I sought to isolate a topic that addressed the relationship between religion and culture in Canadian history. As my graduate work had dealt with the historiography of Atlantic Canada, it seemed sensible to build on this background in regional studies. Concurrent with these considerations was the desire to address a subject area that would allow for the inclusion of material culture sources. My professional background as a museum curator had helped me identify some of the methodological problems inherent in trying to combine verbal and nonverbal evidence. I wanted to have an opportunity to wrestle with these concerns within the disciplinary framework of history.

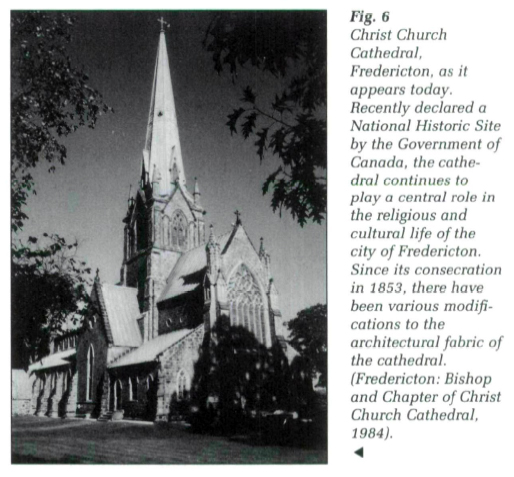

18 In spite of these various considerations, all arrived at quite deliberately, there was a parallel series of thoughts influencing my quest. They had to do with a kind of intuitive feeling, with the response or reaction I felt upon entering some New Brunswick churches. I wondered what it was about certain churches that made me "feel" at home; that caught my attention and changed my mood. I recognized that these impressions were very subjective, but nevertheless wished it were possible to find a place for such sentiments in the larger study. If the physical setting of the church moved me in certain ways, I speculated that it must have moved those of earlier generations as well. But how and why? What did all this have to do with topical themes in regional historiography? Could there be any legitimate connection between feelings and facts in the realm of history? As I mused on these issues from my office on the University of New Brunswick campus in Fredericton, the spire of Christ Church Cathedral stood as a solitary sentinel towering over the elm trees in the distance. It became a visual point of reference for me, as it had for generations before. I wondered why, and decided to try to find the answer. That took me to Bishop Medley and the people of the Confederation generation, to his churches and the architecture and liturgy of those churches and to the styles and sensibilities of that time. It became clear that my topic had something to do with the Gothic Revival and its impact on Victorian New Brunswick.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 619 A basic premise of material culture theory is that an artifact exists as a product of human thought, in action, at that time in the past when the object was made and then used.23 There is no such thing as pure feeling or pure thinking. It is always feeling and thinking directed toward something (or somebody). This unity between the person and the object, between mental activity and the object toward which the mind is directed, allows for the analysis of human intention as expressed in and through artifacts. Such intentionality is conveyed through the object's form and its function(s).

20 Ideas are intangible, and no matter how powerful they may be, no matter how essential they may be to our understanding of historical events, they cannot actually be seen or touched. For this reason, it is problematic at best as to whether or not ideas can be faithfully preserved over time and, therefore, whether or not the historian can accurately interpret their meaning in history. On the other hand, artifacts are tangible. Their accurate preservation over time is less problematic. They represent particular aspects of the past in a material form which continues to exist in the present. The concreteness of the artifact, its visibility, its perceptibility, is its most important quality. It exists today as a piece of history; as a real link between the modern investigator and those being investigated. Its actuality is a factor in its authenticity.

21 I eventually concluded that the purpose of my research was to establish factual criteria from which to understand prevailing notions of aesthetics and sensibility in nineteenth century New Brunswick. As in most areas of cultural history, the themes in this study can be at times nebulous and at times obscure. Aesthetic awareness, although fundamental to that Victorian phenomenon we call the Gothic Revival, can be elusive and difficult to pin down. This is particularly the case if one limits oneself only to printed and manuscript sources. This is why the physical properties of the artifact play such an important part of this study. Correctly identified and carefully interpreted, artifacts can serve the historian by existing as an additional category of evidence. In the context of this study, artifacts were central in the investigative process. Church furnishings and buildings were considered as artifacts, as concrete evidence of human thought (including belief, emotion and opinion) in operation at the time of construction and use.

22 No methodology can exist in a vacuum. The research strategy outlined here is the result of wide reading in history and related disciplines, is constructed on the foundation laid by a select group of scholars who have explored many of these same issues respecting the use of material evidence,24 is elaborated after much sharing of information and insights with others interested in the intellectual significance of the artifact,25 and ultimately is refined after much experimental field work with the artifacts in question.

23 Early on I had to give some thought to the criteria I would use in selecting my verbal and nonverbal sources. As described in the outset of this article, I decided to concentrate on the Anglican experience in New Brunswick. This meant a systematic study of New Brunswick Anglican history as represented in the surviving documents and artifacts. As a category of material evidence, the objects and structures of Anglican worship have certain advantages. They are relatively easy to locate, they exist as a sizeable sample, they are typically found in their original context and setting as opposed to being located in a museum storeroom, attic or auction warehouse, and are often well preserved by church authorities. Moreover, to understand the meaning of artifacts, it is best to begin at the point in their appearance in social and cultural interaction when one can be fairly certain of what they represented and to whom. In their original location in the church, religious artifacts have the advantage of being clearly associated with the act of worship and tied to identifiable denominational practices and doctrines. Church buildings and artifacts tend to be reasonably well documented when compared with other categories of material culture, especially those held outside public collections. Though certain denominations and even individual congregations kept more extensive data on the church building and its contents than others, on the whole, congregations kept organized records, documenting their decisions and sometimes even their attitudes and preferences toward the physical setting of worship.

24 At this point I decided on the terms of reference for a preliminary survey of surviving Anglican material culture in New Brunswick. This survey was designed to be representative in terms of the various geographical regions in the province, chronology and architectural style. The survey covered the entire Diocese of Fredericton, which coincides with the geographical limits of New Brunswick; it examined surviving examples of churches built over a period of years extending from the late eighteenth century to the end of the nineteenth century; and it addressed instances of both Georgian and Neo-Gothic church architecture.26 The artifact and architectural data base for this study was extensive and varied and was accumulated through systematic field work involving on-site inspection of individual churches where objects and buildings were examined, catalogued and photographed.

III

25 The first stage of artifact analysis can be called Level One.27 It commences with the recognition of five basic properties of every artifact: material, construction, function, provenance and significance. The analysis of these five properties occurs in sequence so that the discernment of artifact-related data is cumulative. Just as in traditional historical research on archival sources, where the exercise is made up of the accumulation of both specific detail and preliminary speculations, the analysis of an artifact results in data which is partly factual and partly impressionistic. The first property, material, encourages the analysis of the composition and overall appearance of the various elements which come together to create the object. Construction points to the physical articulation of the object: here one carefully considers its dimensions, proportions, style, decoration, condition, how it was fabricated, and the quality of craftsmanship. Function addresses why the object was created and how it was used. Provenance looks at the chronological story of the piece in question. Here the interest is on when and where the object was created and used and by whom it was created, owned and used. Significance has to do with the object's meaning in its earlier context(s) to its maker(s), owner(s), user(s). Here, the investigator takes the data derived from the previous steps and attempts to synthesize where possible. For instance, the investigator notes his or her own intuitive reaction to the object. Having already reflected on the object's intended function, the investigator also considers possible unintended functions the object may have served.

Display large image of Figure 7

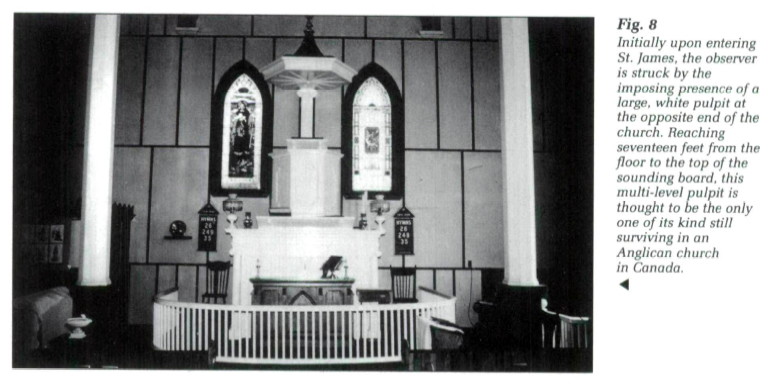

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

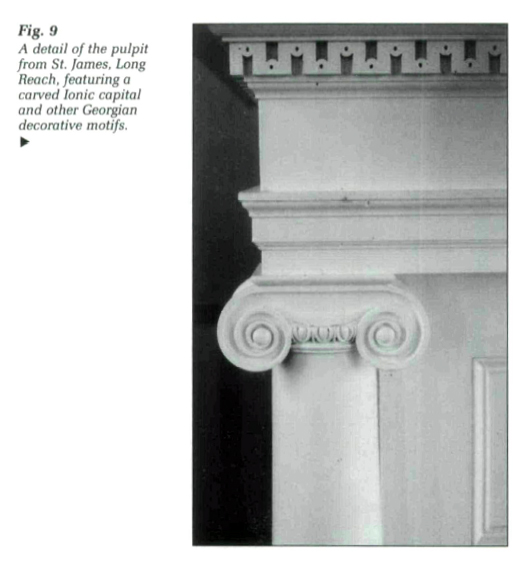

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

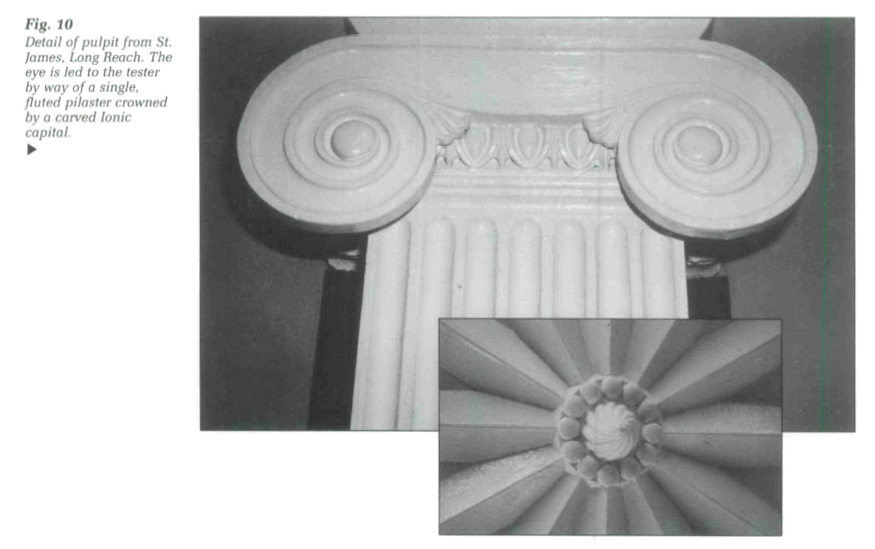

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

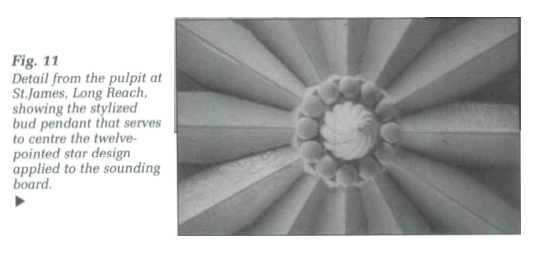

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1126 To this sequential examination procedure is added a four-step process that pertains to the exact source from which particular information and insights about the object are derived. The first step is to read the five properties of the artifact based exclusively on observable data, that is, information gleaned through meticulous scrutinization of the object itself. The second step sees the investigator reconsider the five properties of the artifact, this time based on an analysis of comparative data, namely, other similar or related objects. Next, after the maximum amount of information has been derived from all nonverbal sources, the investigation moves to a consideration of available verbal sources. Here the five artifact properties are illuminated by bringing archival and other forms of documentation to bear on the investigation. The fourth and final step is designed to encourage the investigator to draw conclusions respecting each of the five artifact properties.

27 By establishing several discrete steps for examining the object, this procedure encourages the investigator not to make automatic assumptions but to be methodical, to note detail, to be aware of intuitive linkages occurring in his or her own mind, to be conscious of mental predispositions and to carefully distinguish between complementary relationships that may exist between verbal and nonverbal sources. These steps also allow for the work of one scholar to be retraced by another, thereby permitting the second investigator the opportunity to confront the same artifact sources to determine if the original conclusions were sound.

28 A second and more advanced level of artifact analysis used in this study is referred to as Level Two. Until this point, the object research has had individual artifacts as the sole focus of the enquiry. The aim has been to ascertain as much as possible about the particular object. At this stage the enquiry has been open-ended; the object has been an end in itself and there has been no attempt to bias the analysis of the object by trying to force it into prearranged patterns of research of categories of thought. Until now the procedure could be characterized as that of "cataloguing" the object in as comprehensive a manner as possible. The investigator observes the artifact, say a Neo-Gothic altar, as a whole, and physically experiences its colour, proportion, material, and its setting. The piece makes an impact, in its ambiguities and its unity, its patina and its contours; meaning begins to emerge. The meaning is largely sensory and is assimilated not with words (which are written in retrospect as a secondary, verbal response) but through the initial visual encounter with the artifact. This phase in the reading of the artifact is identified as Level One. Significantly, in Level Two, the focus changes from the object to the larger research question. Here the goal is to determine to object's potential as a historical document that has something to say either qualitatively or quantitatively about a particular historical question. At this stage the investigation is no longer open-ended but has a precise aim: The intention is to reach beyond the artifact to the wider scholarly theme being studied. Here the procedure rests on the clear definition of a research objective and hypothesis. This additional layer of enquiry transforms the investigation from a necessary, albeit preliminary, cataloguing process to integrate the artifact into a process of creative scholarship.

29 The two levels of enquiry build one on the other, and as such are dependent on each other. By itself, for example, Level One would have limited value as a scholarly procedure because its focus is restricted to a single object rather than a larger framework of ideas. On the other hand Level Two, by itself, would be handicapped without the benefit of a preliminary phase of artifact analysis designed to reveal a comprehensive series of facts and impressions about the object. Once this supporting data on the object is in place, however, the investigator is then able to determine whether or not to integrate the item into the larger research strategy. Thus not all the items examined at the Level One stage will be carried over for scrutiny in Level Two. Also, for those artifacts that are carried over for Level Two analysis, not all the facts and properties associated with the particular object will be of interest, but only those aspects of the artifact that speak to the larger historical question(s) being investigated.

30 Having now identified a select group of objects which are worthy of further analysis, the investigator proceeds carefully through the same discrete steps all over again. Level One must be done in the field. Level Two can be carried out in the office, working from detailed photographic records and from specific catalogue notes on the object in question. So, once again the researcher considers the implications of the object's material, construction, function, provenance and significance through means of observable data, comparative data and verbal data, but this time in relation to the larger question(s). The general questions being posed will result in many more specific queries being asked at each stage of the Level Two procedure. Some of these secondary questions will take the investigation along new and creative paths to more advanced and refined levels of analysis.

31 To sum up then, Level One isolates potentially significant artifacts and catalogues their properties. From this large data base, Level Two selects those artifacts bearing directly on the research problem, and examines them specifically in relation to the research problem. The three-decker pulpit in St. James Church on the Kingston Peninsula will serve as an illustration. In my initial survey of liturgical furniture found in Anglican churches throughout New Brunswick, this piece was subjected to Level One analysis. I carefully noted its properties, compared it to other known examples and tried to document its history in parish and local history records. Following the Level One phase, I consolidated my notes and, in the process, was able to clarify and revise my research design. Gradually it became clear which individual buildings and objects had the most to say in relation to the transition from Georgian to Gothic in nineteenth century New Brunswick. I determined the three-decker pulpit to be one such artifact for reasons outlined in detail in my dissertation. My assessment of the pulpit is a combination of what I judged to be salient information and impressions gleaned in the course of subjecting the pulpit to both levels of enquiry. The full significance of the piece, in relation to the larger topic under consideration, did not emerge until the pulpit was taken through the various discrete steps of Level Two analysis.

32 It is helpful to compare what actually takes place when an investigator encounters manuscript and material sources. Although sometimes taken for granted, there is, of course, a particular research technique that enables the investigator to assimilate and interpret the data contained in manuscript sources. This technique has been learned, practiced and refined to a considerable extent by the investigator long before ever entering the archives or library, and is a prerequisite to any form of scholarship. In simple terms, it is the ability to read words, when they are grouped together in paragraphs, pages and books. There is a complimentary approach to research, which is much less well established. It is by no means taken for granted and it is frequently not a functioning part of the historian's methodological tool-bag. Indeed, unlike the well-honed capacity for reading words, most scholars have had no training whatsoever when it comes to reading things. In this respect "illiteracy" runs rampant.

33 Despite the anxiety of the old-school historians, it is possible to read the language of objects for scholarly ends. There is at present no accepted technique for reading things that even comes close to the standardized rules for reading literature. Nor is there likely to be in the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, procedures for reading objects do exist. These procedures endeavour to be systematic and retraceable, and they are designed to encounter the objects grouped together in room settings, buildings and larger collections of artifacts which comprise the cultural landscape. The development of procedures for object-reading is still at a primitive stage. Consequently, the requisite techniques tend to be tedious and idiosyncratic, adhering to the particular intellectual temperaments and disciplinary agendas of individual scholars.

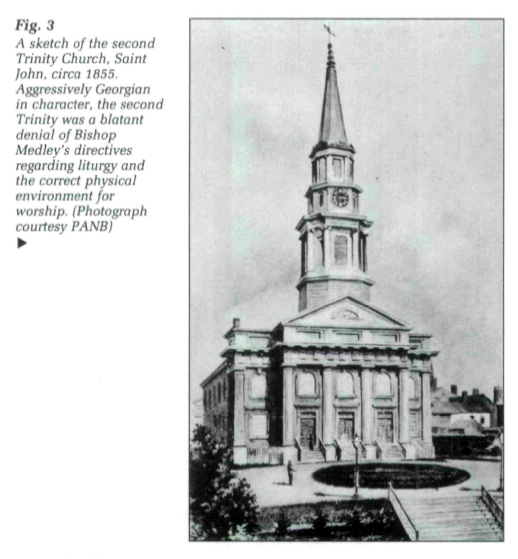

34 The chart which follows illustrates a series of steps or research procedures that reflect the approach employed in this study of New Brunswick's Gothic Revival. In reality, of course, the various steps were not entirely separate, one from the other. Still, I have tried to graphically indicate the various phases in my research in an effort to demonstrate how material culture analysis can be part of a larger research strategy.

IV

35 We would do well to pause here to acknowledge a basic dichotomy. Art Historian Samuel Laeuchli, in his provocative discussion of the methodological linkages between the icon and the idea, has observed,

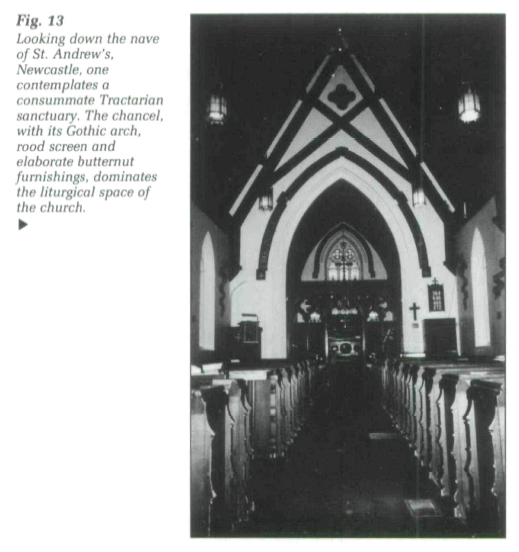

36 Visual reality can never be fully translated into the language of words. The flood of affective impressions that occurred when a believer entered one of England's great Gothic cathedrals—Lincoln, York or Salisbury—or, closer to home, one of New Brunswick's Neo-Gothic country chapels—St. John's, Chamcook; or St. Andrew's, Newcastle; or St. Paul's, Londonderry—can not be entirely reconstructed. But partial reconstruction is possible, and certainly desirable. The alternative—to ignore potential avenues of cultural analysis—is unacceptable. So we must return to these questions: How did the material culture evidence illuminate the findings of this study? How did it refine our understanding of the complementary parts of Medley's vision? How did it clarify our understanding of parish sensibilities?

37 Ideas emerging from the work of a variety of scholars help to clarify these questions. Moreover, such interdisciplinary insights can serve to expand the parameters of artifact studies. For instance, in his classic formulation "Artifact Study: A Proposed Model," American decorative arts historian E. McClung Fleming distinguished between "product analysis" and "content analysis."29 Product analysis, according to Fleming, refers to the ways in which a culture leaves its mark on a particular artifact. Content analysis signifies the ways a particular artifact reflects or influences its surrounding culture. This reciprocal pattern describes New Brunswick's Gothic Revival. In and through Medley's churches, we see (through product analysis) that particular objects were examples of British cultural imperialism; they reflected both formal and vernacular impulses in religion and culture. Yet at the same time (through content analysis) the objects were central to the new aesthetic preferences embraced by New Brunswickers in the later Victorian years; they represented a move away from Georgian toward Gothic sensibilities.

38 In the context of such a two-way movement in cultural perception, it is instructive to review Eric Hobsbawm's notion of an "invented tradition." An invented tradition signifies a set of practices guided by explicit rules and ritual, highly symbolic in orientation, designed to impress certain values and behavioural norms through repetition within a particular population or group. Further, an invented tradition seeks to establish continuity with an idealized past.30 It represents a process of formalization and ritualization often in direct response and as a contrast to socio-cultural change and uncertainty. Hobsbawm makes reference to such phenomena as the pageantry surrounding British monarchy, or Lord Baden-Powell's invention of the Boy Scout movement, or the symbolic and ceremonial paraphernalia of the Nazi movement, to mention but a few instances of invented traditions from the recent past.31

39 The invention of tradition is a little studied yet immensely rich field for historians. The newly established "tradition" can exist as an indicator or symptom of developments that might not otherwise be recognized or easily identified. In essence, they are evidence.32 More specifically, this evidential quality is often embodied in the material manifestations that survive the event or process in question. Hobsbawm explains:

Here we could add that the collection of Anglican ecclesiastical artifacts in New Brunswick reveals the story of cultural change from "Georgian" to "Gothic" sensibilities in ways that official church pronouncements and the clerical and secular press will not. The invented tradition in this instance was the particular liturgical and material features of Tractarian worship. Bishop Medley's introduction of this form of Anglican worship into the life of the New Brunswick church can be most clearly seen and measured in the surviving material culture of Anglican worship.

40 A third consideration is the idea of an artifact serving as a visual metaphor. The metaphor as a mode of analysis in both the humanities and social sciences has received increased exposure of late.34 Of particular assistance for this study were the writings of historian Robert Nisbet and cultural anthropologists R. P. Armstrong and James Fernandez.35 They establish that a metaphor is much more than a figure of speech. It is, according to Nisbet, "a way of knowing...a way of proceeding from the known to the unknown...a way of cognition in which the identifying qualities of one thing are transferred in an instantaneous, almost unconscious, flash of insight to some other thing that is, by remoteness or complexity, unknown."36 The role of a visual metaphor in material culture analysis, then, is to help the investigator be sensitive to a possible "thought-image" occurring in the mind of an individual or group of individuals in the past. Such thought-images were the direct result of the physical properties, the structure, style, finish, content, of the artifact in question.

Display large image of Figure 13

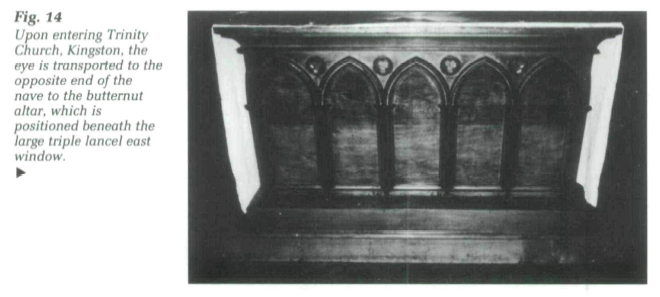

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14 Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 1541 A thought-image can, of course, also be the result of a symbol. The essential difference between an artifact as symbol and an artifact as visual metaphor is that, to use Armstrong's terms, the symbol "represents" whereas the visual metaphor "presents."37 An altar table in a New Brunswick parish can be both a symbol and a visual metaphor. As symbol, the table represents, typifies, stands for the Eucharist, the sacrament of communion within the Church. The craftsman who fashioned the table and those who used it are aware of what it "represents." As visual metaphor, the table presents, prompts, imparts a thought-image of something other than the sacrament, something transmitted to the observer by virtue of the physical characteristics of the object. In this instance, the ideas emanating from the table, being "presented" by the piece, may be beyond what the craftsman consciously intended. A visual metaphor, then, is an active thought-image that is evoked through interaction with the material properties of an inanimate object, thus stimulating the mind of the observer to elucidate an abstract pattern of thought.38 Through this process, something invisible and elusive is made perceptible and is accorded an objective quality. Like the idea of an invented tradition, the notion of visual metaphor in relation to artifact analysis helps pinpoint historical patterns of thought and feeling associated, in this instance, with the material culture of the Victorian Church.

Conclusion

42 A century ago, those who studied the physical fabric and furnishings of a country chapel or a city cathedral considered that they were engaged in the "science" of ecclesiology. They maintained that their pursuit was a science because of its methodical procedures and its antiquarian exactness. The ultimate goal of their work was theological. Today, there are still a few souls who study chapels and cathedrals. Yet this work is certainly not scientific nor does it have any sacred ambitions. But there is a certain "method" to this "madness."

43 The prospect of a new kind of historical synthesis continues to captivate many scholars. Yet their quest for a more unified approach to diverse sources has been frustrated by the inherent evidential uncertainties of non-traditional documents, such as artifacts. As the debate continues over the merits of the interdisciplinary field known as material culture studies, basic questions remain as to precisely how these pieces of history known as artifacts illuminate the past. Consequently, much of the present preoccupation with the object is focused on the epistemology of the artifact. As scholars gradually come to recognize the interpretative possibilities offered by the artifact they find themselves posing important conceptual questions. This is a seminal process, one that stretches the parameters of historical enquiry. The future of material culture studies rests here.

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16