Articles

The Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory, Chesley, Ontario:

Industrialization and Furniture Design in the Late Nineteenth Century

Abstract

The bedroom suites of the Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory of Chesley, Ontario, provide an excellent example of the impact of industrialization on furniture forms. To produce an illusion of variety, a basic form was slightly altered by adding non-structural ornamentation, or its appearance was changed by using different woods or finishes. These superficial changes made possible the production of a wide range of models and "styles" without sacrificing the economics of large-scale production. Industrialized manufacturing methods ensured the success of the Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory; the design of their products satisfied the demands of the consumer within the constraints of the methods of production.

Résumé

Les mobiliers de chambre de la fabrique de meubles des frères Krug à Chesley (Ontario) nour fournissent un excellent exemple de l'influence de l'industrialisation sur la forme des meubles. Afin de créer une illusion de variété, on ajoutait à la forme de base des ornements non structuraux qui en modifiaient légèrement l'apparence, ou encore on utilisait des essences de bois ou des finis différents. Grâce à ces modifications superficielles, on pouvait produire une vaste gamme de modèles et de styles sans devoir renoncer pour autant aux économies de production à grande échelle. Des méthodes de fabrication industrialisées ont fait le succès de l'entreprise des frères Krug. La conception de leurs produits répondait aux attentes de leur clientèle malgré les contraintes inhérentes aux méthodes de production.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 11 The furniture industry in Grey and Bruce counties occupied a position of economic prominence in the late nineteenth century. An abundance of raw materials and easy access to shipping led to the development of a strong industry with broad national markets. The area, therefore, provides an ideal microcosm for studying the development of industrial furniture production in Ontario.1 The output of a single firm, the Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory, Chesley, vividly exemplifies the impact of industrialization on furniture forms.

2 Located to the north of the heavily settled areas along Lake Ontario, Grey and Bruce counties were not occupied by the first waves of immigration into Upper Canada, but were settled primarily by second-generation Canadians, who migrated northward when the two counties were opened for settlement in the 1850s.2 This recent settlement means that records are available for all phases of the development of these communities, from the first complete census of Canada in 1851.

3 Grey and Bruce counties were in an ideal location for the growth of a local furniture industry (see map). A rapidly increasing population provided a ready market for local craftsmen. A steady supply of raw materials was ensured; the Bruce Penninsula was heavily forested, and Grey County was also a source of easily exploited, high-quality timber. Thus sawmills and other wood-related industries concentrated here.3 These were serviced by a commercial shipping industry focused on the Great Lakes. With the coming of the railways, a larger market opened up and the area's newly mechanized furniture factories were able to expand with the demand for their products. The Grey-Bruce area was, however, far enough away from Toronto to escape domination by that city's larger and more-established industrial community.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1 Display large image of Table 2

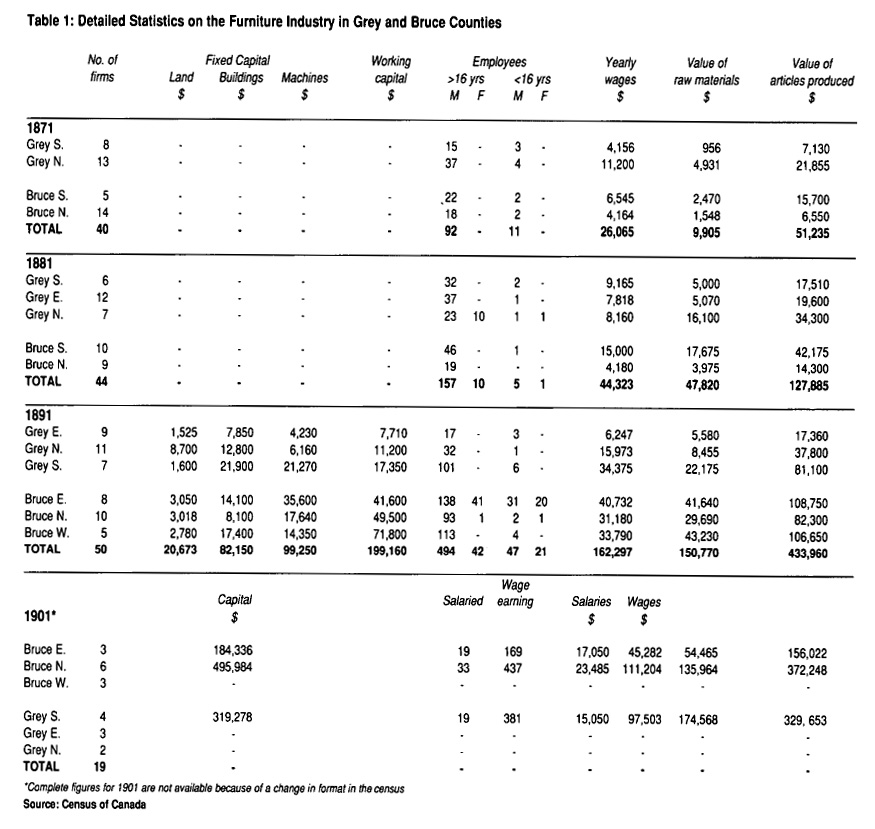

Display large image of Table 24 The population of the Grey-Bruce area peaked in the decade following 1881. The period of pioneer settlement was over and all the arable farmland in the counties cleared and settled. The typical 50- to 100-acre (20- to 40-ha) farm, while able to support one family group, was not of a high-enough quality to allow further subdivision. A labour pool was thus created, which newly established industries exploited.4 In addition, it drew more manufacturers to the area.5

5 The industrial statistics available through the Aggregate Census of Canada illustrate the development of furniture production in the counties of Grey and Bruce (see tables 1 and 2). After the coming of the railways and the population peak, the industry was able to operate at an expanded capacity, reflecting the economies of scale which came with the introduction of machinery into the construction of furniture and the shift to factory production. The producers of Grey and Bruce also had a geographic advantage over those of Southern Ontario, for they were located much closer to the expanding markets of the Canadian West.

6 The trend towards large-scale operations is confirmed by an increase in the number of employees per firm. In 1871 each company had an average of 2.6 employees. This rose to 3.9 in 1881, a slow move which may reflect a gradual adoption of mechanized techniques of production.6 Company size accelerated rapidly, however, to 12.8 employees per firm in 1891, and 84.1 in 1901. This increase in scale is also reflected in the value of production. In 1871 each manufacturer produced an average of $1,281.88 worth of furniture. This grew to $2,906.48 in 1881, $8,679.20 in 1891 and $65,994.08 in 1901. The value of production easily outpaced the growth of the work force. Between 1871 and 1881 the number of employees per firm increased by 50 per cent but the value of production increased 127 per cent. This increase was even more dramatic between 1881 and 1891, when the average number of employees per firm increased by 228 per cent and the value of production by 199 per cent, and between 1891 and 1901 when the increases were 551 per cent and 660 per cent, respectively.

7 Industrialization, however, was not simply an expansion of scale; increasingly, mechanized production dictated changes in design, form and construction. A collection of late nineteenth-century furniture produced by the Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory in Chesley, and now in the Bruce County Museum in Southampton, reveals an evolution of furniture forms in relation to the restrictions of technology. An examination of the history and output of this factory provides an excellent opportunity to study the impact of industrialization upon style and form, for the furniture they made is representative of the factory-produced furniture of the late nineteenth century.7

8 The Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory was established in Chesley, Elderslie Township, Bruce County, in 1885, as an industrial operation.8 Peter Krug, the father of the founding Krug brothers, came to Canada from Germany in 1852. He apprenticed as a cabinetmaker at the Hebner Furniture Company in Berlin (Kitchener), and later ran his own cabinet-making shop in Balaclava, near Tavistock, Ontario. He closed his business in 1875 to go to work at the Hess Furniture Company in Listowel, Perth County. Peter Krug's sons followed him into the furniture industry: the eldest, John went to work for a furniture factory in Cleveland, Ohio; Christian and Conrad, twins, and William, the youngest, went to work for Hess Furniture along with their father. The brother-in-law of the younger Krugs, Henry Ankeman, also worked at this Listowel factory.

9 Attracted to Bruce County because of the ready supply of waterpower and raw materials, the Krug brothers moved to Chesley in 1886. Their first factory was a three-storey frame structure, measuring 52 by 36 feet (16 by 11 m) located on the north side of the Saugeen River. Its machinery was operated by a horizontal water-powered turbine. The Krugs purchased the facing property on the south side of the river in 1891, increasing their access to waterpower, and built a sawmill on the site, giving them control over the supply of raw materials.

10 The Krug Brothers' Factory hauled goods to the railway station with horse-drawn carts until 1901, when the buildings of the Chesley Novelty Co., located near the train station, were purchased and modified. It had been impossible to build a railway siding to the existing factory because of the sharp grade of the river bank. Manufacturing continued at both sites until the winter of 1910-11, when the factory moved into the buildings it occupied until the business was sold in 1988.

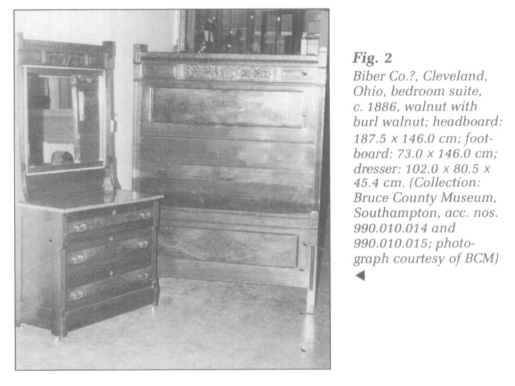

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 211 The Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory produced a broad range of furniture aimed at the growing middle-class market. Although some products were simple and straightforward in style and decoration, others were substantial and lavishly decorated. The furniture produced by Krug Brothers shows the great potential there was for variation within the parameters of factory production and also attests to the broad range of Victorian taste.

12 The styles of furniture reflect the dominant middle-class ethos of the age and share certain common characteristics: a preference for a revived version of a historical style (for example, Renaissance Revival or Victorian rococo); a taste for lavish carved ornament and for substantial proportions, often combined with a top-heavy silhouette; a tendency towards the use of dark or contrasting woods; and the increasing use of veneers and painted finishes to imitate more expensive woods.9 The furniture manufacturers who catered to this market did not set the styles. Rather, they adapted them to suit their needs and capabilities.10

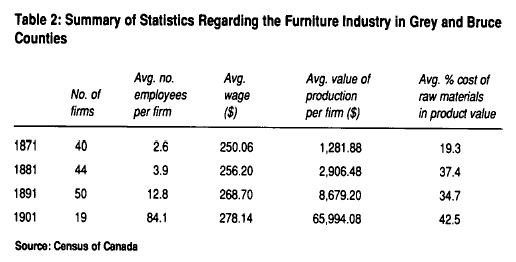

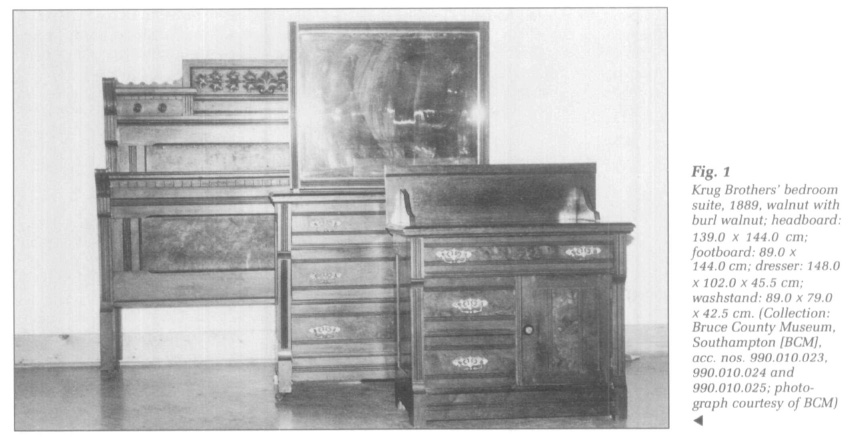

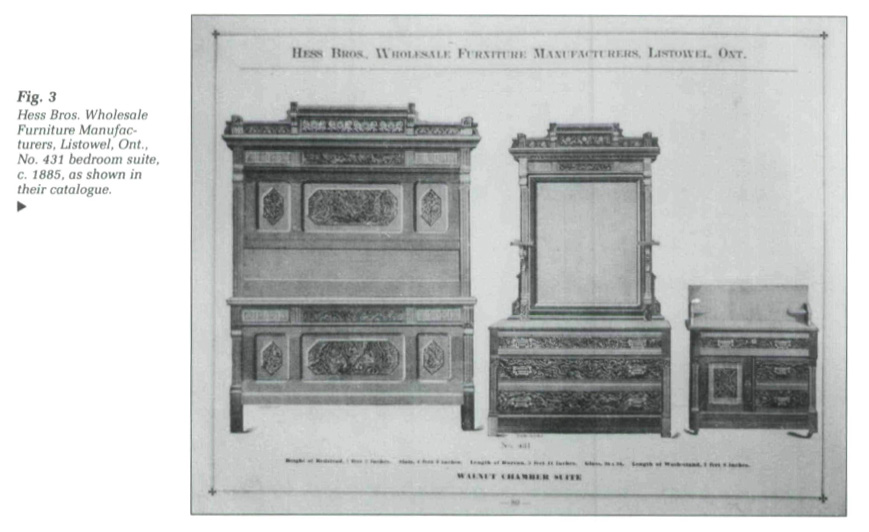

13 This adaptation of existing styles and designs for local production can be seen when the earliest known Krug bedroom suite, circa 1889 (fig. 1), is compared with those produced by two other factories where members of the Krug factory worked before they established their own family business. A bedroom suite (fig. 2) produced circa 1886 by the factory in Cleveland where John Krug worked before the Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory was founded and another (fig. 3) which appeared in the catalogue of the Hess Furniture Company in Listowel, Ontario, show the same general forms and decorative treatment of the Krug suite. The material, walnut with burl walnut decorative panels, is the same in all cases. Decoration, consisting primarily of incised lines and stylized natural forms carved in low relief, is kept to a minimum. The forms are simple and rectangular.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 314 In their shape, decoration and honest use of materials, these suites all follow the tenets of Charles Locke Eastlake, author of Hints on Household Taste, who established himself as an arbiter of taste through the success of this publication.11 The style Eastlake avowed was a simple one: "furniture should be functional, nonostentatious, simple and rectilinear in form, honestly constructed 'without sham o pretense', and ornamented with respect for the intrinsic qualities of the wood as well as the intended uses of the furniture."12 Eastlake's dislike of ornament and preference for simple forms helped popularize the tenets of the Aesthetic Movement. He wrote:

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 415 Eastlake was more popular in the United States than he ever was in Britain, perhaps because of the support given by writers in the American popular press, who helped to disseminate his ideas of good taste.14

16 The Eastlake style proved to be a very easy one to adapt to industrial production, for its shapes were easily reproduced mechanically, and the ornamentation could be produced by machine without any compromised in quality or workmanship.

17 Not all the furniture the Krug factory produced (nor all furniture that has had the label "Eastlake style" applied to it) followed Eastlake's advice directly, as a taste for decoration persisted. The growth of the middle-class and their desire to attain and display the trappings of an established lifestyle pressured the industry to produce furniture that reflected their ideal of respectability. Popular taste therefore gravitated towards substantial, lavishly decorated furniture because it embodied a sense of tradition which the middle-class found themselves lacking.16

18 One of the most important factors in expressing "good taste" was the prerogative of choice. The Victorian consumer demanded a variety of styles from which it was possible to choose the most fashionable, or the one that best expressed the aspirations of the individual.

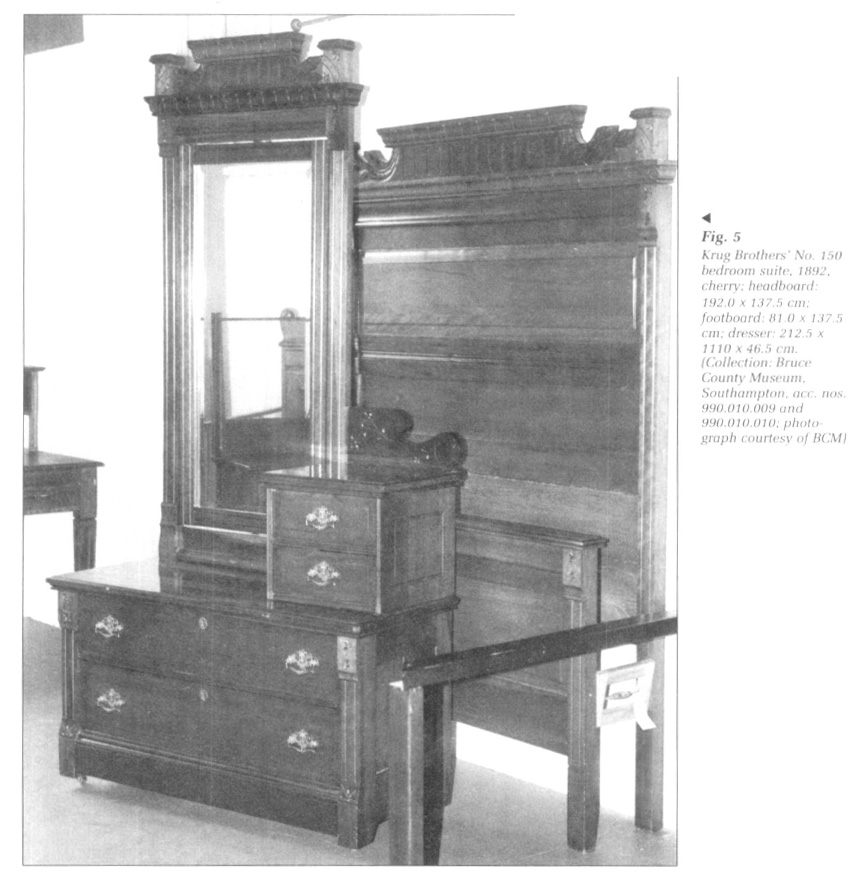

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

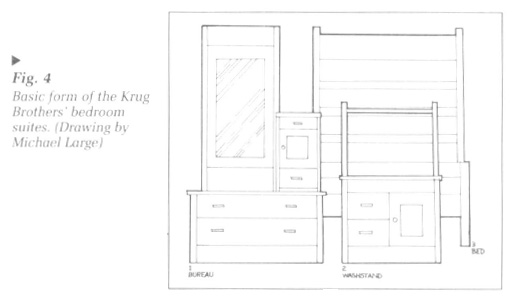

Display large image of Figure 919 The Krug factory attempted to provide a product that satisfied the consumer's tastes and desire for ornament by offering what appeared to be many different styles of bedroom suites. Each year saw a new group of styles. A closer look at these suites, however, shows that this variety is only superficial. The techniques of mass industrial production dictated that the way to offer the customer the most choice, while keeping costs down, was to vary the decoration on what was basically the same set of forms.18 The Krugs' production of the 1890s operated upon this basic principle. All models followed the same basic form (fig. 4), which was varied with applied decoration and the use of different materials and finishes.

20 In the 1892 suite (fig. 5) an elaborate cornice was added to the otherwise rectilinear shape. The decorative carving is simple and executed by machine, but the profile, built up of applied strip mouldings, is complex and gives the impression of lavishness, which is enhanced by the use of contrasting materials. The mirror, unusually, swings vertically. The suite could be ordered in either cherry or oak.

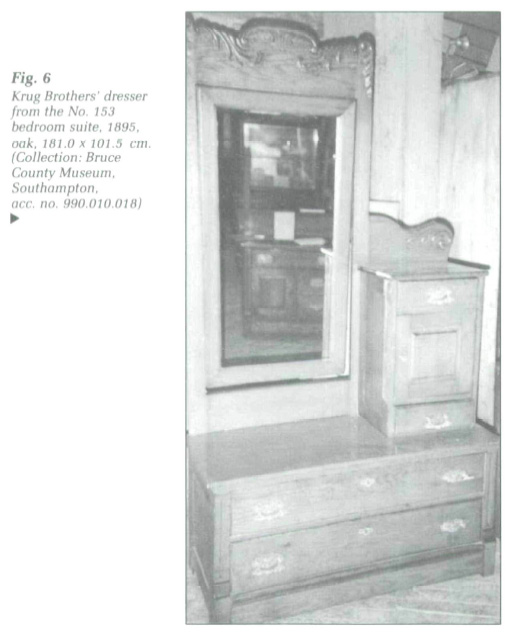

21 The No. 153 suite from the 1895 catalogue (fig. 6) offered a less elaborate profile but no less decorated option. Instead of incised carving, here the basic form was decorated with applied ornament that had been produced by machine and was then glued on to the rectilinear form. This three-piece suite was available in oak for $18.00 wholesale, or in elm for only $9.75.

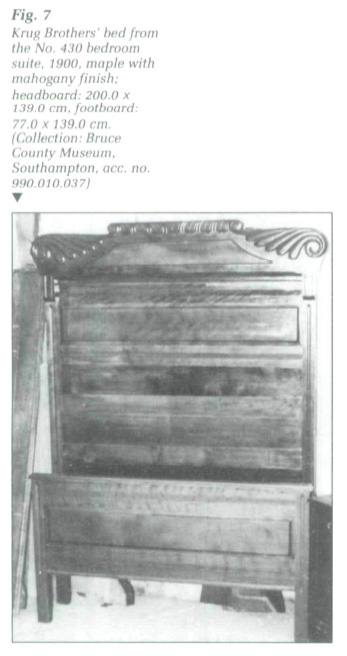

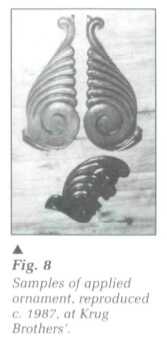

22 The No. 430 suite of 1900 (fig. 7) combined applied carving with incised decoration to offer a somewhat more sophisticated design. The curved forms decorating the head- and footboard of the bed and the mirror of the dresser were also carved separately by machine and applied to the basic form of the suite. The present generation of Krugs experimented with the reproduction of these techniques and produced samples of applied ornament very similar to that on this suite (fig. 8). The No. 430 suite also used finish for decorative effect. The application of a mahogany stain to the maple of the overall construction gives the suite a superficial richness of appearance and warmth of tone.

23 This adaptation of style to the dictates of industrial production was not peculiar to the Krug Brothers'; the offering of choice, however superficial, was common throughout the industry. Ostentatious furniture, a form of conspicuous consumption, conferred a sense of respectability, and when that furniture was factory produced, that respectability came at a reasonable cost.

24 The bedroom suite was an important part of the furnishing of a Victorian home, for it formed a unifying element in a decorative scheme.19 It also provided an opportunity for the display of social status. The more expensive the suite, the higher the headboard and the more elaborate the decoration and the carving.

25 An interesting comparison to the furniture produced by the Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory can be found in the furniture made in Grand Rapids, Michigan; it reflects the same basic tenets of construction and decoration. The overall look of the piece of furniture was varied to satisfy the market, but the actual form was not significantly different because of the strictures imposed by the machinery of manufacture. This required innovative and imaginative design, for while attempting to please the consumer, the designer must also be aware of the economics of production.

The furniture producers of Grand Rapids were also able to create "some fine designs...by simple means and through the imaginative use of a limited number of devices."22

26 The furniture production of both the Krug Brothers' and Grand Rapids furniture factories reflects one of the economic facts of mechanized furniture production: to remain competitive, machinery must be used to its best advantage.

As mechanical means of production are designed for the duplication of forms rather than the invention of them, the industrially produced furniture of the nineteenth century had a homogeneous appearance. "A possible reason for difficulties of attribution in the 1870s [and onward] is the widespread use of the same woodworking machines by factories scattered around the country."24 Indeed, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish the production of one factory from another. This is underlined when the furniture of Krug Brothers' is seen in the context of that produced in other factories in the Grey and Bruce area.

Display large image of Figure 10

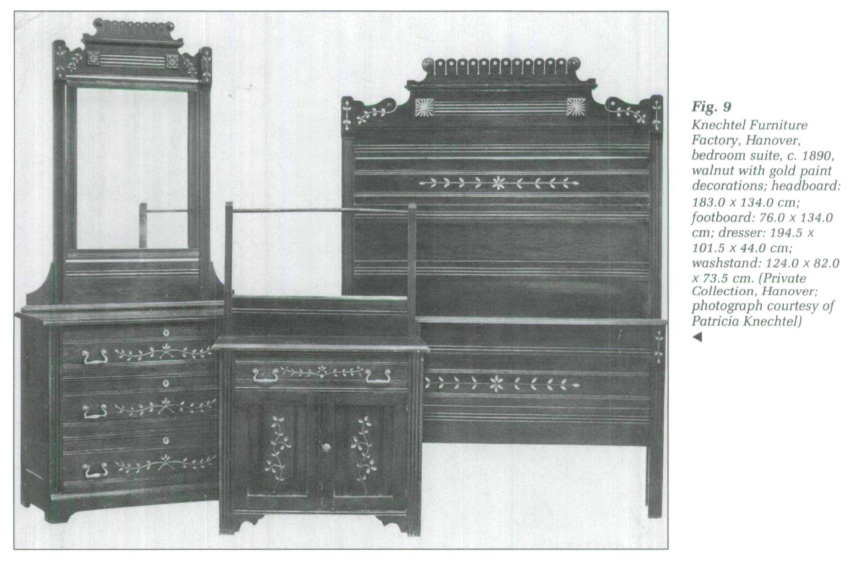

Display large image of Figure 1027 The Knechtel Furniture Factory in Hanover grew to become one of the largest furniture producers in Canada.25 It produced a wide range of household furniture, as is shown by two surviving price lists, from 1892 and 1899, which include tables, chairs, case furniture, and upholstered goods as well as spring beds and mattresses.26 By 1900 the factory contained at least 150 machines, reportedly all of the latest design.27 This "machinery, shafting, gearing, belting and tools" was housed in a complex of sixteen buildings in Hanover.28 For such a successful factory, however, few pieces identified as Knechtel furniture are known. A bedroom suite from 1890 (fig. 9) is the only clearly attributed group predating the factory destruction by fire in 1900. It was owned by the Knechtel Factory itself and kept in their showroom until the firm went into receiver-ship in 1983. The suite is of the same simple rectangular lines as those produced by Krug Brothers' and has incised floral decoration which was most likely executed with a mechanically powered router. It still retains its original dark finish, with the incised decoration defined by gold paint. The drawer fronts, however, are attached with the peculiar "pin and scallop" joint. This is characteristic of the Knapp dovetailer, an American invention that temporarily solved the labour-intensive problem of making conventional dovetails by hand. Used throughout the 1880s and 1890s in Canada and the United States, this unique and easily recognizable joint was abandoned when reliable machinery to execute conventional dovetails was invented.29 The backs of the drawers are held together with simple dowel joints, which could be easily executed by machine.

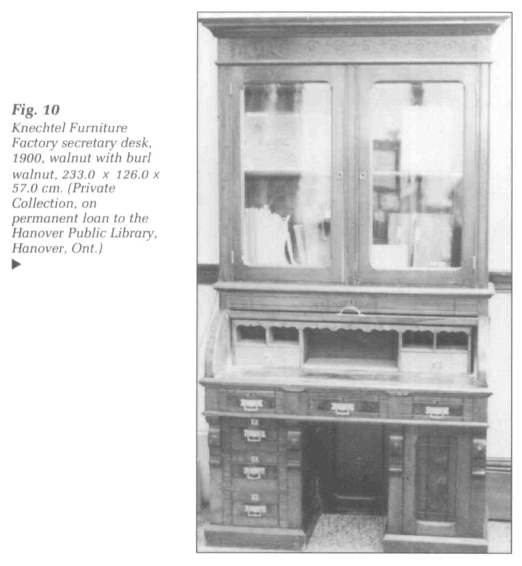

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1128 Another, more substantial piece of Knechtel furniture is a roll-top secretary desk (fig. 10) used by Daniel Knechtel in his factory office from 1900 until his death in 1936. On loan to the Hanover Public Library, this desk is reputed to be the first piece of furniture produced in the new factory after the fire of 1900. It is made of walnut with burl walnut panels and shares the sharp lines and heavy cornice of some of the Krug Brothers' bedroom suites. This weighty feeling is reinforced by the massive scale and presence of the roll-top desk. The drawers in this piece of Knechtel furniture are joined with machine-made dovetails, indicating that in the retooling of their factory after the fire, the Knechtels acquired more-advanced machinery. The ornament is again a floral pattern, incised into the entablature below the cornice, and was most likely executed with a router following a patterned template.

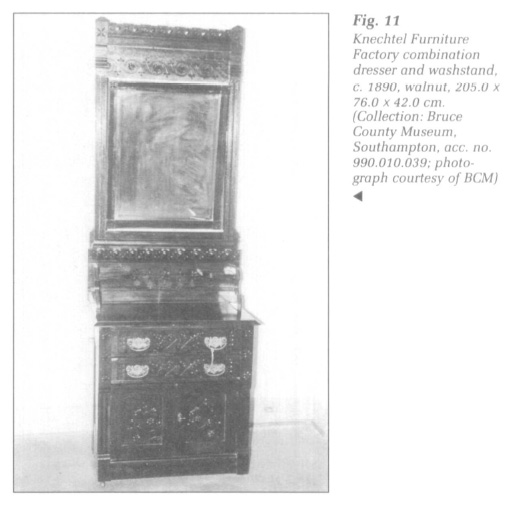

29 An interesting piece of furniture, which clearly should be placed between the two previous examples, is a dresser with a fixed mirror from the Rocklyn Hotel in Euphrasia Township, Grey County (fig. 11). This piece can be safely attributed to the Knechtel Furniture Factory on the basis of its similarity to the two established Knechtel products. Its decoration and materials are similar to the Knechtel bedroom suite of 1890. Both are of a light wood, possibly butternut, stained a dark walnut colour. Both have the characteristic "pin and scallop" dovetailing in the fronts of their drawers, and dowel joints in the back and are decorated with a floral pattern of incised decorations carved with a router; the pattern along the top of the mirror in the Rocklyn Hotel dresser duplicates that on the secretary desk in the Hanover Public Library. Evidently the Knechtels purchased new machinery after the fire in 1900 but did not discard their old designs.

30 It becomes obvious that it is not innovations in form that factory production can be credited with, but innovations in techniques of construction. This is confirmed by an examination of the Canadian patents that relate to furniture. Those patents awarded to furniture factories in Grey and Bruce counties are concerned with the construction and operation of furniture.

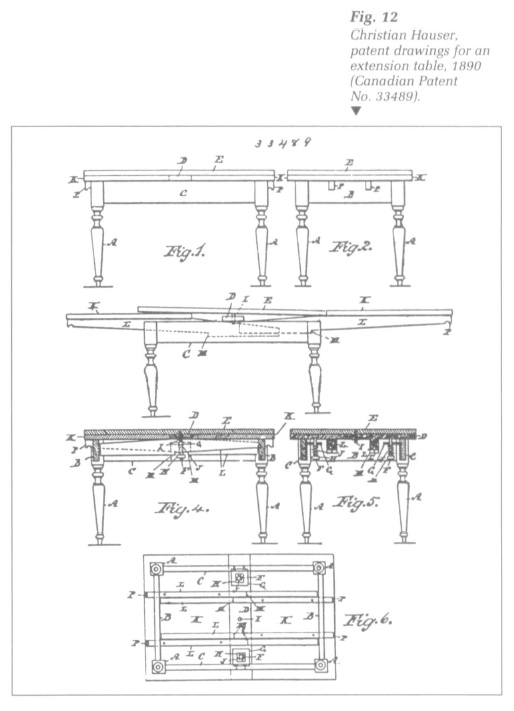

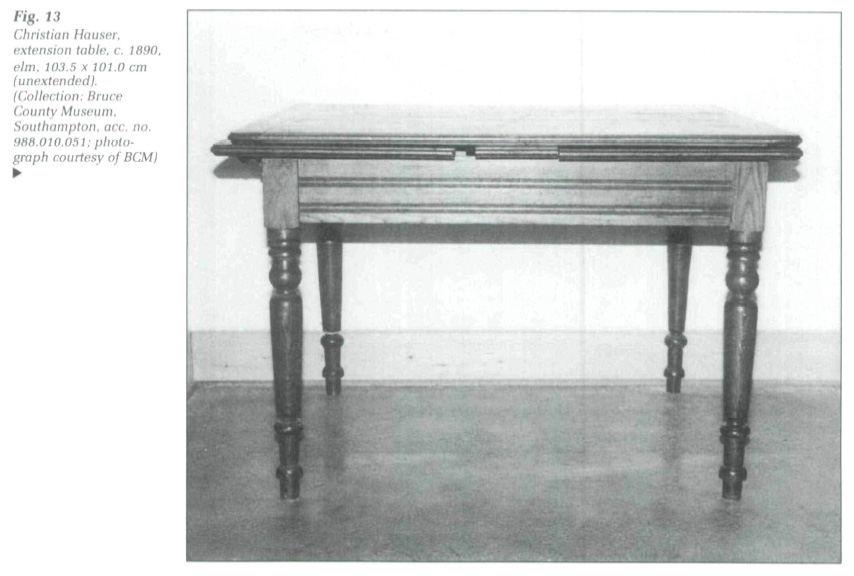

31 One of the earliest patents from the Grey-Bruce area was given to Christian Hauser of Elmwood, Bruce County, on 8 January 1890, for "certain new and useful improvements in extension top tables."30 Extension tables had long attracted the attention of inventors because of the difficulties involved with their operation and the problem of storing the extra leaves.31 In response to the latter problem, Hauser's table had self-storing leaves: two end leaves spring upwards once they are pulled out from underneath the stationary "permanent top," where they are kept in a concealed storage space (fig. 12). An example of this table survives (fig. 13); the design shown in the working drawings is decorated with turned legs. A patent for a similar table, which operated on the same general principle but with a different mechanism, was awarded to J.S. Knechtel on 21 November 1905.32 It also had self-storing extensions which were drawn up from underneath a stable centre tabletop.

32 It was not necessary, however, to patent an entire piece of furniture. Often only working mechanisms and methods of assembly were patented. J.S. Knechtel was able to improve on the operation of his table slide mechanism and patented "a simple, efficient, cheap and easy working adjustable slide for an extension table, which will not be liable to jam or get out of order" on 5 March 1901.33

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14 Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15 Display large image of Figure 16

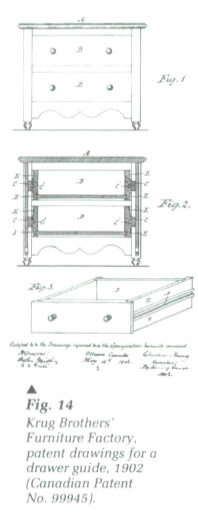

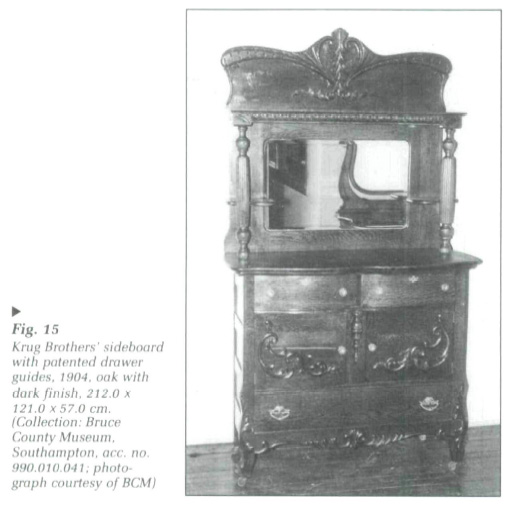

Display large image of Figure 1633 Christian Krug of Krug Brothers' patented an improved drawer guide (fig. 14):

34 As Krug stated, patented improvements of construction methods could save the manufacturer considerable costs and thus make his products more competitive. They could also be incorporated into such existing styles of furniture as the 1902 oak sideboard (fig. 15). Protection of such technical innovations by patent was essential if a manufacturer wished to be sure of maintaining, and perhaps expanding, his market share.

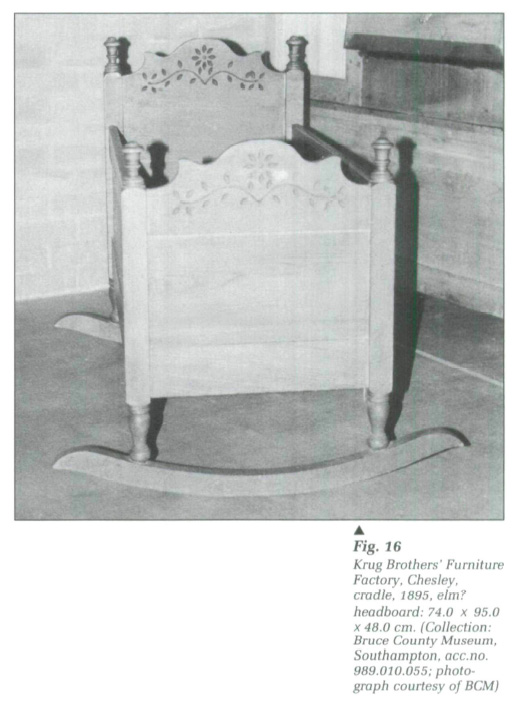

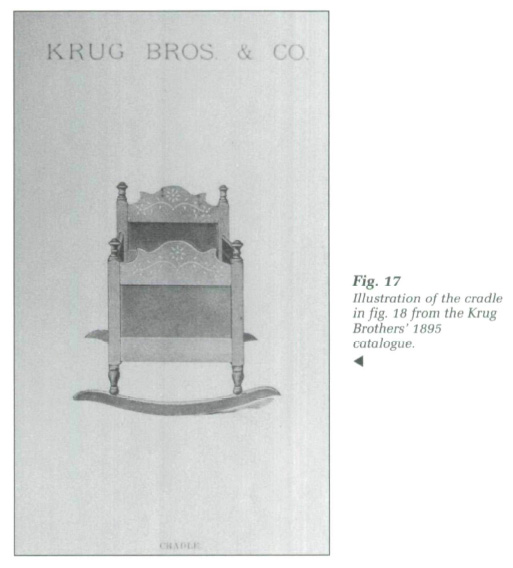

35 Standardized methods of production were ideal for the type of market the Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory catered to, for its predominantly middle-class clientele did not require great innovations in style, only that the style offered be fashionable. Furniture was sold primarily by illustrated catalogue to retail stores. A travelling salesman or furniture retailer would use the catalogue in combination with a current price list to take orders. It was possible to order a cradle (fig. 16) from the 1895 catalogue (fig. 17) for $1.50, for example. This ensured that the factory could produce to order, eliminating the need to carry a large inventory.

36 This strategy was common throughout the industry. The Knechtel Furniture Company used the expanded capacity of its new plant to support concentrated marketing in western Canada.35 A travelling salesman was given a route out of Brandon, Manitoba, to gather sales from the West. He also worked with an illustrated catalogue, from which he took orders, and a price list, which could be easily revised. Most large case-furniture was shipped unassembled to reduce rail freight charges. It was possible in 1899 to purchase an elm wardrobe for $7.00 plus shipping charges, with a discount of two per cent if the balance owing was paid in thirty days and three per cent if the account was cleared within ten days.36 Business in the West improved so much that in 1909 Knechtel's constructed a warehouse in Winnipeg. A surviving piece of Knechtel furniture has been located in Saskatoon.37

37 Perhaps because of its large size, the Knechtel Furniture Factory served as a training ground for many of the entrepreneurs who went on to establish furniture factories in the Grey-Bruce area in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Henry Peppier left Knechtel's in 1909 to set up his own company. He prefigures his departure in a speech he made in 1901:

Display large image of Figure 17

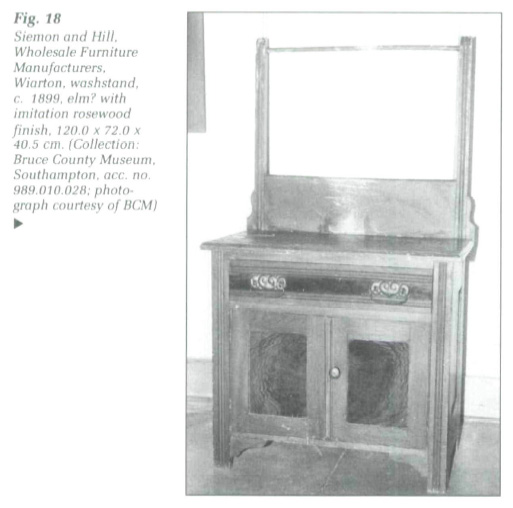

Display large image of Figure 17 Display large image of Figure 18

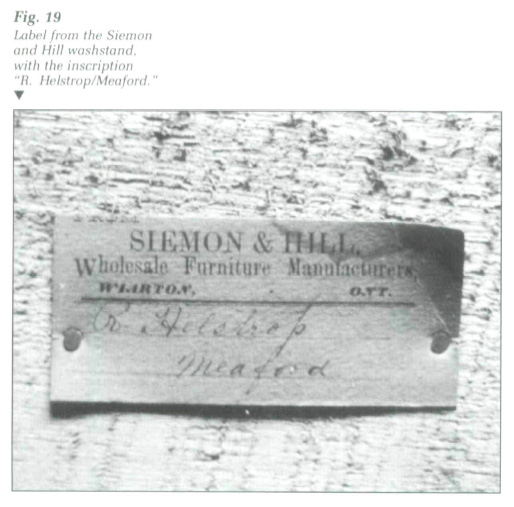

Display large image of Figure 18 Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 1938 A bedroom suite produced by the Siemon and Hill Furniture Company39 of Wiarton, Bruce County, offers an interesting insight into the complex interrelationship between manufacturer, dealer and consumer in the late nineteenth century (fig. 18). The suite was made in Wiarton by the Siemon and Hill Furniture Company, as is shown by the labels found on the back of the headboard of the bed and on the washstand (fig. 19). The name of Robert Helstrop, a cabinetmaker in Meaford, Grey County, is inscribed on the part of label where the shipping instructions are to be indicated.40 While Helstrop is known to have made some of the furniture he sold, the appearance of his name on the label of a piece produced by a furniture factory indicates that he must also have acted as a furniture dealer. The presence of Helstrop's name on the label also helps to date the bedroom suite in question; he died in 1899. Much industrially produced furniture was purchased for resale and was often sold by a small dealer as his own product.41 The fact that most factory-made furniture was unmarked only adds to the confusion.

Display large image of Figure 20

Display large image of Figure 2039 Mechanized production methods allowed for a far greater quantity of furniture to be manufactured, but mass production demanded standardization of forms. By its nature, machinery is designed for the duplication of identical parts. At the same time that mechanized production became widespread, the growing middle-class desired to display their wealth and consciousness of style. Ingenuity was therefore required on the part of the furniture maker to produce an appealing product. Following such arbiters of "good taste" as Charles Locke Eastlake, curves were rejected in favour of simple angular forms, and excess decoration was replaced with restrained carving related to the construction of a piece of furniture.

40 Because the production of a unique product was not possible without abandoning the economies of scale, industrial furniture factories had to meet the demand for variety in style in an innovative way. They altered a basic form slightly through the addition of non-structural ornament, or changed its appearance through the use of different woods or finishes, such as "surface oak." This superficial variety produced the illusion of choice, as it made possible the production of a wide range of models and "styles."

41 The bedroom suites of the Krug Brothers' Furniture Factory of Chesley provide an excellent example of the superficial changes made to a basic form to produce an illusion of variety. Through sensitive industrial design the Krugs were able to meet the needs of a large and diverse market. Industrialized manufacturing methods enabled them to produce on a scale that ensured profit; good design, in the sense that it considered both the demands of the consumer and the constraints of the methods of production, ensured the maintenance of their position in the market.