Articles

Retrospective Analysis of Folk History:

A Nova Scotian Case Study

Abstract

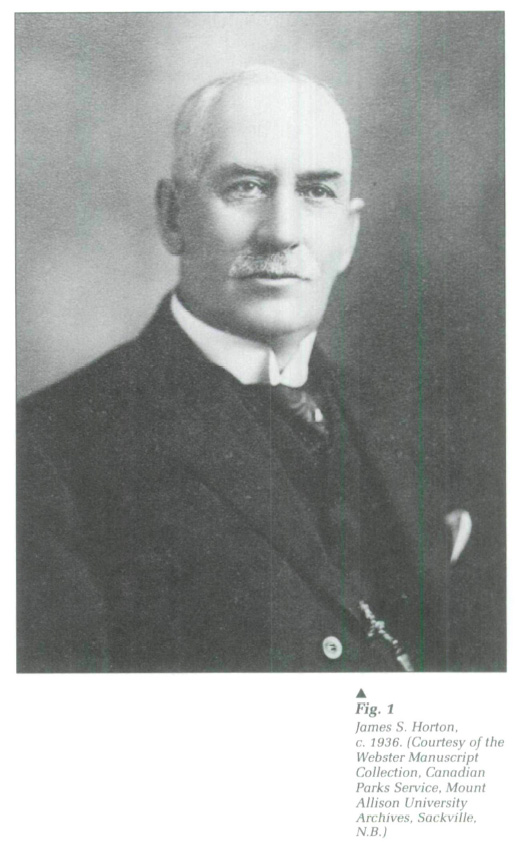

Amherst, Nova Scotia, briefly burgeoned in population and economic significance during a period of rapid industrialization in the late nineteenth century. The methodologies of folklore, history and material culture studies are combined in this article to analyze a surviving example of folk history, as expressed through an artifact collection, from this community. The collection of 111 items was amassed by James S. Horton, a barber in Amherst. Between 1900 and 1930 he ran a "folk museum" at the back of his shop. From a study of the collection and an examination of the collector's life, the author tries to extract the town's perspective on the past. As the bulk of the collection has become part of the Fort Beauséjour Museum, the author argues that the earlier perspective still has relevance today.

Résumé

Amherst, en Nouvelle-Ecosse, connut un bref essor démographique et économique durant une période d'industrialisation rapide à la fin du XIXe siècle. Dans le présent article, l'auteure fait appel aux méthodologies combinées de l'étude du folklore, de l'histoire et de la culture matérielle pour analyser un exemple vivant d'histoire du folklore qui s'exprime par une collection d'objets recueillis dans cette ville. Cette collection, composée de 111 articles, fut amassée par fames S. Horton, un barbier de Amherst. Entre 1900 et 1930, il tenait dans son arrière-boutique une sorte de « musée des traditions populaires ». L'auteure tente ici d'extraire de l'étude qu'elle a faite de la collection et de la vie du collectionneur la perspective de la ville sur le passé. Comme le gros de la collection est maintenant intégré au musée du fort Beauséjour, elle entend démontrer que cette perspective chronologiquement révolue est toujours valable aujourd'hui.

1 Development and/or manipulation of historical consciousness and cultural awareness is a growing area of interest, ripe for multidisciplinary study.1 This article suggests one approach that combines the methodologies of historian, folklorist and material culture specialist: retrospective analysis of folk history as expressed through an artifact collection.

2 Folk history constitutes the "native" view the general populace of a community or region holds of its past. Drawing on the work of folklorist Edward D. Ives, Larry Danielson explains folk history by contrasting it to oral history:

Charles Hudson juxtaposes folk history with the discipline of history. Borrowing from linguistic terminology he describes history as an "etic" or outside analysis of what is significant, while he suggests folk history might best be thought of as "emic" categories and perceptions.3 Folk history represents a component of an individual or community's world view that is expressed outside of the confines of formally organized institutions such as museums and art galleries.

3 While to date most studies exploring a group or community's sense of history focus on activities of contemporary institutions that give rise to an awareness of the past,4 this analysis, through the presentation of one case study, explores what Charles Hudson refers to as emic perceptions of the past as represented by an informally amassed group of artifacts. The collection, begun circa 1900 by James S. Horton, a Nova Scotian barber, exposes something of one community's early twentieth-century perspective on its past. It is a vision that not only held functional importance for townspeople of the day but continues to have relevance for contemporary residents. More generally, the case study contributes to our growing understanding of the development of historical perspective and lays groundwork for future analysis of contemporary efforts in historical interpretation and exploitation.

J. S. Horton

4 An artifact-based analysis of folk history must consider the individual who initiated the artifact collection. In this case, James Horton was a recognized authority on the history of Amherst, Nova Scotia, for most of his adult life. For much of that time he was also custodian of an informally generated collection of artifacts that made up, for lack of a better term, a "folk exhibit" or "folk museum."

5 James Stewart Horton was born in 1863, one of at least three children of Nancy and Samuel Horton, who operated a farm in Leicester, a small agricultural community in northern Nova Scotia. As a young man Horton moved to Amherst, a market town about ten miles (16 km) from his home, where he found work in the stables of a local senator.

6 Horton's early years in Amherst coincided with the community's development as an industrial force. During the 1880s the town's industrial base expanded rapidly so that by 1900 Amherst was a manufacturing centre of national importance. Two short years later the town's population had doubled to 10,000, its approximate size ever since. The home of many foundries and factories, its line of products ranged from stoves and bathtubs to pianos, caskets, woollens and soft drinks. By 1907, however, the tide had turned and the town's capital was being absorbed by national interests with head offices located in Quebec and Ontario. In the 1930s Amherst's industrial significance had declined dramatically, and the town was well on the way to its present status as a service centre for the surrounding farming district.

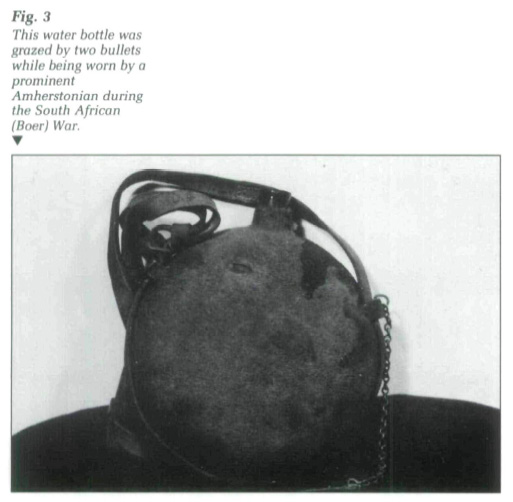

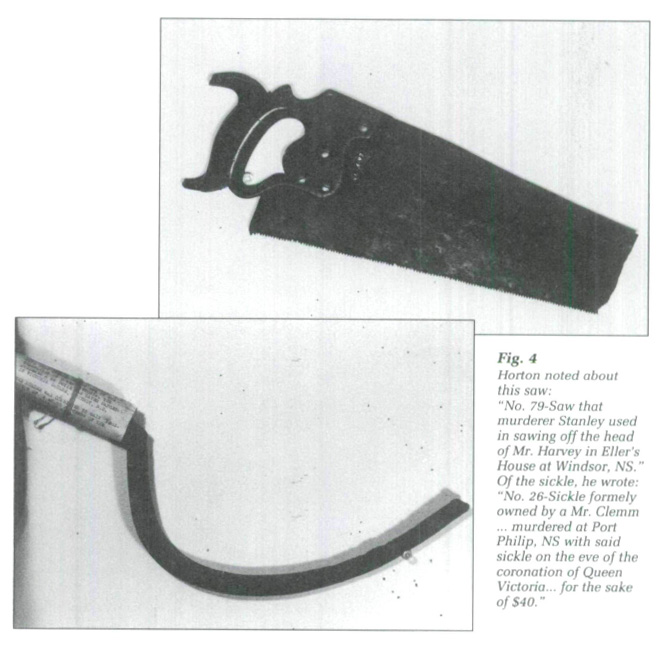

7 As a young man Jim Horton recognized the needs of a growing population of industrial labour; he left the senator's employ, drew on some earlier experience he had as a barber, and went into partnership with a man by the name of White. Within a few years Horton opened his own shop in one of the town's best hotels, and in 1896 the Amherst Daily News5 claimed he had "one of the finest outfits of razors seen in Nova Scotia." By 1903 Horton had moved again and had added a fourth chair. Three years later he opened a shop near the town's main intersection and there he worked until the day before his death on 15 December 1939. At that time his barbershop was described as having been "an Amherst landmark for half a century" (ADN, 15 Dec. 1939: 1).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 18 In many ways Jim Horton's life was unexceptional. Like other young men of his day, he participated in the prevalent pattern of outmigration that took him from the Maritimes to Boston. There he received training as a barber but, also not untypically for his generation, he returned home when economic conditions improved. In 1891, at twenty-eight years of age, Horton married Lillian Simpson, a carpenter's daughter who "conducted a dressmaking establishment" in Amherst (ADN, 2 July 1908: 4). After Lillian died suddenly in 1908, Horton raised his daughter as a single parent and cared for his aging widowed mother. In April 1915, two years following his mother's death, Horton married again, this time to a widow, Minnie Estell Hewson née Lawrence. The distribution of his estate following his death suggests Jim Horton maintained harmonious relations with his daughter from his first marriage, as well with his two stepchildren.6 This supports the community perception of Horton as expressed in a newspaper tribute to him at the time of his death:

The editor describes Horton as "a kindly man in every sense" who had "hundreds of friends" (ADN, 15 Dec. 1939: 1).

9 Some characteristics of Horton's personality and experience particularly suited him for the role of folk historian and folk museum curator. The editorial written at the time of his death comments that he "had an agreeable personality which invited confidence and his nature was kindly. He had a long and varied experience and out of this he was able to meet most anyone on the same level." Horton's early experience in the stables and his long career as a barber brought him in close and extended contact with traditional male expressive culture. He would have heard countless narratives, many of which undoubtedly centered on people and events in the town's past. His obituary supports this supposition with the comment that his shop was "a mecca for the older citizens of town and county" (ADN, 15 Dec. 1939:1). Horton, then, probably had ample opportunity to expand his own knowledge of the town's past.

10 James Horton had other qualities that contributed to his reputation as a historian. He enjoyed record keeping and after returning home from a two-week "motor trip" through the Maritimes and the New England states in 1923, he informed the local press "that his repair bill for the thousand mile trip was but twenty-five cents and that he had the same air in his tires as when he left home" (ADN, 14 Sept. 1923: 4). This brief newspaper account touches on a passion of Horton's: he loved to travel. Over his lifetime the newspaper chronicles trips to the United States, Calgary and Vancouver. Local residents still remember the pride Horton took in his car and describe how he would often drive around the town and county with his second wife.7

11 Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Jim Horton liked the unusual. Although described as a quiet, unassuming man, he demonstrated a definite interest in the extraordinary. For example, when he chose to have a dog, he bought a beautiful purebred Chow that was to be the only of its breed in the town.8 The most dramatic and public display of his interest in the remarkable took the form of an artifact collection he housed in his barbershop. This exhibit of unique, and often macabre, items was added to by patrons so that for over thirty-five years Horton's barbershop was the unofficial museum of the town and an important interpretative influence in Amherst's folk history.

Amherst's "Chamber of Horrors"

12 The transformation of Horton's barbershop into a folk museum was a gradual and, certainly in the beginning, an unconscious effort. The first reference to any item in Horton's shop (other than equipment or fixtures connected to his business) is a brief newspaper mention of a photograph displayed there. The picture showed a man with what was thought to be the longest beard in the world (ADN, 19 Nov. 1901: 3). Four years later Horton was displaying objects that had no connection to barbering. On 28 August 1905, the Amherst Daily News reports "The latest addition to Mr. Horton's 'collection of curies' [sic] is a shark's jaw presented to him by Lawson Burgess of Amherst. Burgess got it a couple of years ago in South America. It is of peculiar structure and worthy of examination." When Horton donated his collection to the area's first official museum, which opened in 1936 on the site of Fort Beauséjour, it had grown to at least 111 objects.9

13 Horton's collection is difficult to categorize for it is an eclectic group. Like the shark's jaw, many pieces belong to the realm of natural science or history. He exhibited two bottles of water, one from Amherst and another drawn from a nearby river; snake skins from Central America; crocodile skins from Egypt; an elk's tooth mounted in gold; the skull of a large sea turtle; swords from swordfish; bark from a tree in South America; and a piece of petrified wood from Arizona. One Amherstonian now in his eighties vividly recalls a stuffed fish that used to hang in Horton's shop when he was boy.10 Not all of Horton's natural science exhibits were static, however. His shop seemed to be the appropriate destination for anything remarkable, whether living or dead. In 1906 when a bat was captured in an engine room of one of the factories, it was placed on exhibit at Horton's barbershop. From 1910 to 1916 at least one live woodchuck resided in the shop's front window, and townspeople observed its habits as they tried to predict the severity of winter or the arrival of spring.

14 Approximately twenty items in the collection have an association with a significant place, person or event from the local, national or international past. There are relics from the forts of Beauséjour, Annapolis Royal and Louisbourg; and a key to the front door of "old Dalhousie College," Halifax. Horton displayed several souvenirs of celebrities and members of the Royal Family; for example, he had a window pulley from Henry Longfellow's residence. There are mementoes of the early days of the Intercolonial Railway, the Perry expedition to the North Pole, the sinking of the Titanic, the burning of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa and the Halifax Explosion. What were considered to be exotic peoples, such as the Indian and Chinese, are represented by about a dozen artifacts including an "Indian drinking cup" and Chinese playing cards. A few objects, such as miner's lamps, illustrate early industrial technology.

15 Over 50 of the artifacts in Horton's shop bear some connection to military or criminological history. There is an Indian club; French duelling pistols; arms from the American Civil War; a wide assortment of pistols and revolvers; swords; bullets and knives from the South African (Boer) War; and a selection of murder and suicide weapons of local repute. One of the more dramatic items remembered by Amherst residents is a piece of the noose that hanged a Nova Scotian after he was convicted of the murder of his wife. Not surprisingly, the many macabre items in Horton's collection have received the most attention, as in a 1914 newspaper report that describes Horton's barbershop as "a chamber of horrors" (ADN, 21 April 1914: 1,8). If one moves beyond this singular element of the collection, however, what do the artifacts reveal of how this man and his clients saw themselves, their town and their collective past? What relevance did their historical perspective have for their present?

James Horton, His Collection and Folk History

16 Retrospective analysis has its own inherent limitations. It is now difficult, if not impossible, to determine the motivations that transformed Horton's barbershop into a folk museum or, once in motion, what kind of "collection policy," if any, guided its expansion. Did Horton express specific interests to his customers, thus shaping the collection, or did his patrons bring in artifacts spontaneously, making their own decisions as to what was appropriate for display there? Did he solicit particular items or refuse any of those brought to him? For example, is the emphasis on criminological materials a reflection of Horton's personal fascination or does it demonstrate a more general interest shared by many of the shop's patrons? While these questions may never be conclusively answered and represent some of the restrictions of such a study as this, Horton's personal notes as well newspaper accounts promoting recent acquisitions indicate the collection was more than one man's pet project. Amherstonians enthusiastically supported the growing collection by donating items and by coming out to see the latest addition.11

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 217 When examined closely, this group of artifacts reveals a particular view of the town's past that reflected broader societal attitudes and fulfilled important functions for community residents during the first three decades of the twentieth century. For example, the collection displays the tendency, still prevalent in Horton's day, to create "cabinets of curiosities" that display an eclectic mix of unique and/or exotic natural specimens and cultural artifacts.12 The natural science content of Horton's collection further illustrates a Victorian preoccupation, for it represents only one of many collections to develop all over the world at this time as part of an unprecedented explosion of interest in the collection and display of natural history.13

18 Like others of their time who lived through industrialization and/or experienced the pressures of deindustrialization, Amherstonians sought release from their fast-changing world in the exotic and the rare. They also looked for escape from their present in the area's cultural history of a century or more earlier. The majority of Horton's artifacts are linked to military skirmishes fought over the local forts of Beauséjour and Cumberland, thereby commemorating an era in Nova Scotian history that Brook Taylor describes as "a realm of romance" for nineteenth-century writers of local history.14 As David Lowenthal says of Victorian Britain, "No other society had so rapidly embraced innovation and invention or seen its everyday landscapes so thoroughly altered."15 The distant, unthreatening past afforded Nova Scotians in general, and Amherstonians in particular, a mental refuge from their fast-changing world. On the other hand, events of the more recent past might be overlooked completely. The Chignecto Ship Railway—a railway that would have cut across the Chignecto Isthmus, transporting ships overland between the Bay of Fundy and the Northumberland Strait, but that ended in political disaster in the 1890s—was still fresh enough in the minds of residents that it is not commemorated in the collection.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 319 Although reflective of more generally held attitudes, Jim Horton's collection held immediate value for local residents. Both natural and man-made artifacts in Horton's shop relate to specific individuals connected to the community. Beverly Laird donated a snakeskin brought home from Central America, and the Brooks family displayed sand and a tarantula spider from Burma, India. These "natural wonders" combine with exotic cultural artifacts, such as sunglasses used by the "Esquimeaux" in Winnipeg, duelling pistols from Quebec, and an Indian mortar from Alaska, to suggest adventures that span a continent. The Baptist minister's son exhibited a water bottle that had been grazed by two bullets when worn during the Boer War; the sheriff donated a revolver used in the American Civil War; a businessman brought in spurs and barbs from a bullfight in Mexico; and the local member of Parliament gave a German gas mask he had brought home from France.

20 While these objects were no doubt valued for their exotic and/or educational value, they may have had a more immediate importance. As Amherst grew rapidly in the first years of this century, it attracted a work force from Canada's Atlantic provinces and from along the eastern seaboard of the United States. Just as in other industrial centres throughout North America, men and women left familiar farming and fishing communities to work and live with others of varied backgrounds in a new urban setting. All had individual life stories that were unknown to their new neighbours and coworkers. In Amherst the blind fish-pedlar had lost his sight after he suffered eye damage while working as an RCMP officer in the Yukon; the clothing pedlar came from a well-established farming family in Lebanon; and the Chinese laundryman had a wife and family in Canton that Canadian immigration laws prevented from joining him. Certain artifacts in Horton's shop would have offered patrons an opportunity to remember and share individual pasts, for as Yi-Fu Tuan comments, "People look back for various reasons but shared by all is the need to acquire a sense of self and of identity. I am more than what the thin present defines."16 To ensure the past does not seem fictitious, one tries to share it with others. Through the artifacts in Jim Horton's shop, some of the town's residents were able to tell their stories and share something of their past lives. By publicly displaying artifacts that spoke of significant past accomplishments and experiences, individuals could reaffirm their self-identity and find reassurance that their past contributions still had value in a new setting.

21 In addition to symbolizing an individual resident's depth of experience beyond town boundaries, the artifacts might have helped to introduce fellow townspeople to each other. Horton's artifacts were part of the process whereby strangers became friends and neighbours, who together forged a community. The collection contributed to a resident's ability to assess more accurately another individuals' present life circumstance or opinion and ultimately to understand better this person. Horton's artifact collection would have supplied a burgeoning community with some of the necessary contextual background required to transform a strange place into home.

22 An important characteristic of home is that it has familiar landmarks. Artifacts in Horton's collection that relate to features of the local landscape helped new residents transfer "space" into "place."17 Their presence would have introduced or reminded of the history of the area: for example, the battles associated with the local forts. They would have allowed the resident to interact with the past of the immediate locale, connecting contemporary Amherstonians with those who had lived in this landscape at other times. This would have been an important initial and continuing function of the collection, for as Bernard Norling comments, "A consciousness of a common past and common traditions is the most basic thing that knits together the members of any group, be it a family, a church, a nation, or some other."18

23 Although it is very unlikely that Horton or any of his clients would have consciously defined their perception of the past, it represented the "right" kind of history for the town, as determined by contemporary needs. A significant concern during Amherst's rapid expansion was the establishment of acceptable social boundaries and the development and maintenance of a social hierarchy. Early civic records and newspapers chronicle the town's struggle to provide adequate policing and to organize committees of the town council to address the social needs of some of the town's residents.19 Whether intentionally or not, Jim Horton's artifact collection reflects this concern with order and control. In one sense the concentration on weapons, all from conflicts where "our side" emerged victorious, emphasizes the advisability of conforming and reifies the correctness of the victor's viewpoint. The interest in local crime shows an emphasis on punishment, and interestingly enough, no murder is included where the culprit was not caught and punished. Artifacts relating to the capture and punishment of deviants, shown most dramatically in the piece of one murderer's noose, reinforce community boundaries of acceptability and warn against the dangers of not creating and maintaining rigidly held norms. If Yi-Fu Tuan is correct in his assertion that "identity of place is achieved by dramatizing the aspirations, needs, and functional rhythms of personal and group life,"20 items in Horton's collection promoted identity of place by articulating the community's commitment to establishing and maintaining boundaries.

24 A community's folk history is also shaped by what is not included. Although the barbershop itself was largely egalitarian in that it was open to most members of the town, it was closed to those of Afro-Canadian descent. Blacks could not have their hair cut in the shop for the entire period of Horton's proprietor-ship and significantly there are no artifacts that relate specifically to any members of Amherst's black community, numbering approximately 300 in the 1910 census. Acadians, the largest minority group but of low status within the general community, are poorly represented in the collection. Micmac and Chinese populations, much smaller minority groups, are depicted through oddities such as the Chinese playing cards that lend exotic flavour. Not surprisingly the feminine perspective is also overlooked; with the exception of three women all the donors were men and the majority of the audience undoubtedly would have been male. Most items relate to the town's elite families, and it is the contributions and experiences of many of the community's most wealthy and prestigious male residents that are best documented. The collection was one means of establishing hierarchy, and it helped to reinforce this order throughout its lifetime in the community. The majority of Amherstonians clung on tightly to the social divisions that organized the town during its early days of industrialization long after deindustrialization was bringing about social change. The collection represents one means used to justify the distribution of wealth and prestige that remained.21

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 425 From the recollections of the men who visited Horton's shop, prompted by the presence of artifacts displayed there, part of Amherst's folk history was created. According to David Lowenthal, this version of folk history would have been an authentic and vivid one for participants. He declares, "Memory, history, and relics offer routes to the past best traversed in combination."22 Housed in a barbershop, one of the town's designated spaces for "talk," the artifacts would have acted as mnemonic devices for the retelling of a particular story, the reminiscing about an event or person in a personal or collective past. Customers to the barbershop experienced history by talking about it, discussing it and undoubtedly occasionally arguing about it before reaching some kind of consensus. Unconsciously Jim Horton was adopting aspects of the "new museology," which argues that the meaning of artifacts is maintained by discourse. Together, Horton and his patrons formulated a folk history that filled their contemporary needs; it not only sought to clarify their town's place in a wider context, but created a version of the past that offered escape from industrialization and reaffirmed the community's social order.

26 Today the historical vision Jim Horton and his clients created of a remote, well-ordered past, full of great men and impressive accomplishments, still has relevance for Amherstonians. In some respects it is the perspective that continues to inform emic historical thinking, in the form of oral accounts that circulate—some based on the words of men who spent time in Horton's shop—and on the artifact collection of the Fort Beauséjour Museum.23 For example, like Horton, his donors and clients, all those charged since with the documenting of Amherst's history have been male.24 A few women have earned reputations as authorities on particular families, but the public realm of history has been firmly male dominated. In large part, the ethnic experience in Amherst still remains to be addressed, and those early social divisions upheld by Horton continue to exert subtle influence on the town's neighbourhood divisions as well as on individual family's social standing and reputation.

27 While one cannot hold Horton or any of his contributors directly responsible for shortcomings in contemporary historical interpretation, the more obvious biases of earlier collections such as Horton's may point to particular directions where a closer examination of present-day efforts is warranted. The collection certainly warns of how historical interpretation may become tradition bound. Horton's collection comprises several groups of similar artifacts: for example, it contains six keys and a number of pistols. Presumably once a key or pistol was displayed in the collection, contributors saw it and brought in more. While not damaging in itself, this codification indicates how quickly a view of history may become standardized and expectations limited.

28 Like the one housed in Jim Horton's shop, many private collections have found their way into public institutions. By remembering these "folk" origins we may understand better how ordinary people of any earlier time view the past and thus illuminate our own historical perceptions. This cursory examination of one early, informal attempt at preserving and interpreting the past hints there is much to be gained from a cross-fertilization of historical and folkloristic methodologies and much to be gleaned from the roots of folk history.

This article was prepared with the help of the staff of Mount Allison University Archives and Fort Beauséjour National Historic Park, Canadian Parks Service, Environment Canada. Thanks also to Peter Latta, Dorothy and Cyril Ratchford, Annie and Russell Hunter and Bob Gouthreau.