Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

A Ukrainian Church Exhibit at the Canadian Museum of Civilization

1 The completed History Hall of the Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC) will contain a reproduction of a circa 1930-35 prairie Ukrainian church. The History Hall is a vaulted space measuring 110 metres by 30 metres, with a maximum height of about 18 metres. The exhibits will be spatially organized, roughly, into three rows of eleven exhibits each, through which the visitor will meander in chronological sequence, ending in the late twentieth century. Many exhibits are "framed" by symbolic structures—like the prairie Ukrainian church—which are themselves artifacts of Canada's historical landscape and evoke associations of time, place and culture.

2 Research for the church exhibit has focused on four areas of material culture: the architecture of the church, the interior painting, the artifacts produced by Ukrainian craftworkers and the artifacts deriving from commercial sources. Other research is directed at themes to be interpreted through sound, live performances and publications. This report will discuss some findings related to the work of carpenters and painter-craftsmen.

The Museological Context

3 The director of the CMC, Dr. George MacDonald, has repeatedly stated his conception of the Museum's new public face in a series of addresses and articles.1 The idea of "cultural tourism" figures prominently, that is, offering a cultural message in an entertaining fashion. Among other interpretive methods, one is to allow the visitor to experience another culture by creating a historic environment, complete with inhabitants. This approach affects the roles of museum historians and curators, who must ensure the historical and contextual veracity of a greatly expanded repertoire of exhibit media, and requires a standard beyond the financial reach of most institutions.

4 The CMC's pan-Canadian exhibit mandate includes themes and artifacts that have been the preserve of specialized museums, museums that reflect a regional or local, often "ethnic," desire to maintain and present a heritage. For example, until recently, the bearers of the Ukrainian heritage have been intimate members of the community, but that heritage has now become a component in the larger exercise of Canadian myth-making. This trend is related to other aspects of Canadian cultural policy such as education and multi-culturalism.

5 The drawing together of diverse historical experiences in a uniform style to foster cultural tourism is disquieting for those who wish to hold on to, in Ernst Nolte's phrase, the "familiar and beloved." Yet the challenge thus raised is timely, and articulates the paradoxical context in which museum historians and curators, conditioned as somewhat selective heritage guardians, find themselves. Their annual audience at the CMC is forecast at two million, representing a touristic, expansionist culture that winnows and appropriates the accumulated knowledge of other cultures, both past and present. The taste of these visitors, as much as the historical material, defines the work of the museum exhibit planner.

Recent Investigation

6 Systematic research into the material culture of Ukrainian churches remains active in the Prairie provinces. In general, the work began with salvage operations by members of the Ukrainian community in response to the abandonment of rural churches after 1960. Inventories and photographs have since been taken of existing buildings, and surviving members of congregations have been interviewed. These inventories form the basis for systematic study of Ukrainian church material culture.

7 The Church Historical Information Retrieval Project (CHIRP) was researched for the Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies between 1971 and 1975 and compiled as research files by 1978. The files, now at the CMC in Ottawa, contain information on 146 Saskatchewan churches of East European congregations (sixty-nine of which are Ukrainian Catholic). Each file contains a photo essay (exterior, interior, grounds, informants), a building questionnaire, a congregation history based on interviews, and line drawings of building plans and iconostasis elevations.

8 Anna Baran's Ukrainian Catholic Churches of Saskatchewan contains information similar to that of CHIRP on some 166 Ukrainian Catholic parishes in Saskatchewan.2 Occasionally the two sources contradict on the dates of details by a year or two. The omissions that arise from the questionnaire method are evident in comparing the two Saskatchewan sources. The two sources do not cover all the East European churches in the province, the most important gap being in the Ukrainian Orthodox group. Despite these limitations, the public information on Saskatchewan churches remains the most complete of any province, as reflected in the dominance of Saskatchewan material in the following discussion.

9 In the course of developing the Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Village near Edmonton, the Alberta Department of Culture has prepared several detailed reports of church material culture in the 1927 to 1935 period. As case histories of land use, structures, artifacts and congregations, these reports are comprehensive. Moreover, the three churches that were the objects of analysis have all been moved to the museum site and restored. A subsequent photographic inventory of Alberta churches has assembled the systematic information needed for further research projects.

10 Two researchers with the Alberta Department of Culture have broken ground in the systematic analysis of church material culture. Diana Thomas Kordan's article "Tradition in a New World: Ukrainian Catholic Churches in Alberta" presents her analysis of formal aspects of Ukrainian church architecture and the historical influences these forms represent.3 Radomir Bilash has published a study of the Alberta painter-craftsman Peter Lipinski,4 who was active from about 1912 to about 1972 as a church and icon painter. Lipinski was an early popularizer of church painting in Canada and, as a painter-crafts man, was possibly the most prodigious, having worked in at least fifty churches.5

11 Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation began its study of Ukrainian churches in 1978 with an inventory of East European churches.6 Since then, the work of recording church information has been taken up by the Manitoba East European Heritage Society (MEEHS) based at St. Andrew's College in Winnipeg. By the late summer of 1988, MEEHS had compiled research files on some fifty congregations and churches, with work in progress on a hundred more, emphasizing the photography of material culture. MEEHS researchers are preparing a publication illustrating the continuity in Manitoba of architectural forms from Ukraine.7

Early Trends in Church-Building Activities

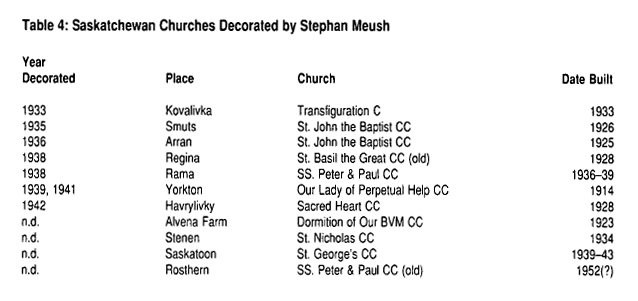

12 Construction of Ukrainian churches in Saskatchewan continued at a fairly steady pace from about 1900 to the 1950s (table 1). In Catholic parishes, about a third (80) of the construction (246) from 1902 to 1977 was for replacement churches. Construction of first churches was concentrated in 1902 to 1929 and 1940 to 1959. Replacement construction was steady from 1920 to 1959.

13 The construction of a church was the biggest communal project that most congregations were to organize; therefore, social organization of such construction is worth noting. The earliest churches were community-built with hewn logs, perhaps under the informal supervision of several men. The community's memory of traditions in Ukraine provided the only architectural guide.

14 By the mid-1910s, a strong trend began toward the hiring of a carpenter-craftsman, whose local reputation as a general building contractor might grow into a regional reputation as a church builder. These carpenter-craftsmen changed the architecture of Ukrainian church-building, not only in the techniques and social organization, but also in formal aspects. They adapted North American construction materials, especially pre-cut lumber, and techniques such as "balloon" framing. In the organization of their work, they were the paid foremen of crews of volunteers from the congregation. They also changed the form of prairie churches. While adhering to a sense of the Ukrainian in their architectural form, they preferred to emulate urban and even metropolitan forms such as the Kievan or Byzantine, rather than to perpetuate the regional "folk" forms of the first churches.

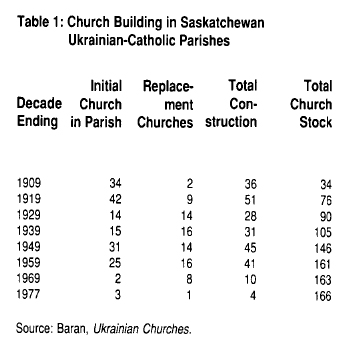

15 In Saskatchewan, some prominent carpenter-craftsmen were Wasyl Huziak and the Semeniuk brothers of Arran, Fedor (Fred) Vistovsky, O.M. [?] Slonetsky, Harry Sulyma, the Manitoban Ivan Ticholyz and the Edmontonian Josef Janishewsky (see table 2).

16 These builders, as well as several less busy carpenter-craftsmen, worked within a remarkably uniform style. They built domed, cruciform churches with polygonal apses and gabled roofs. Except for earlier churches, they usually added two frontal towers, a feature introduced by Roman Catholic missionaries in Alberta.8 Most of their churches were replacements for outgrown or destroyed pioneer buildings. As a group, these builders are significant for creating in Canada a style of architecture which harkened to Ukrainian metropolitan forms, even as the traditional forms built by the first colonizers fell from favour and disappeared.

17 Another gradual trend was the emergence of builders who were self-conscious religious architects. In Saskatchewan, the first was Professor Pawlychenko of Saskatoon who built St. Mary's Ukrainian Orthodox Church at Melville in 1924 and Holy Trinity Orthodox Church at Canora in 1928.9 Another was Philip Ruh, whose reputation spanned the country and who had a busy career as a religious architect from 1916 to 1960.10

18 A third trend emerged in Saskatchewan around 1940, as builders with little stylistic remembrance of the Old World began to add design features which can best be described as modern. A telltale feature of one builder of the 1940s and 1950s, Nicholas Zary, was his use of bold curves in the facade detail of the gables.11 Other Saskatchewan builders who took up New World forms were Illya (Ilko) and Alex Sembelarous (Cymbalarous) of Prud'homme, Theodore Buchko of Ituna and Hryhoriw (Harry) Shalley of Goodeve.12

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 119 The work of these builders was organized like that of the earlier carpenter-craftsmen. They also held a similarly prestigious social place in the region, as is suggested in the renovation of a church at Humboldt in 1973. The congregation wished to add an entrance and a facade to their rectangular gable-roofed church, and engaged the elderly Nick Zary and Illya Sembelarous from nearby Prud'homme to build in their distinctive style.13 In the stylistic licence of these builders, and in the cognitive architecture of Pawlychenko and Ruh, one finds the formal and social precursors of modern church architects.

20 During the period of renewed parish founding in the 1940s and 1950s (see table 1), the practice of communal church building was revived. Descriptions of such construction are reminiscent of the early settlement period, except that the term "volunteers" is inserted to describe the later builders. The architecture emulated metropolitan Ukrainian forms, comparable to that of the carpenter-craftsmen of the 1920s and 1930's, but the execution of those forms was less accomplished. The churches were built as cheaply as possible, without iconostases or commissioned iconic painting, and were often sheathed with asphalt fake brick. Thus, the experience of the parish pioneers of the post-war decade in Saskatchewan echoes the early settlement years.

21 In summary, the material from Saskatchewan bears out several historical trends in Ukrainian church building. The first is the abandonment of regional folk styles as practised by the early settlers. Equally important is the spread of metropolitan Ukrainian forms of architecture, as emulated in wood by the carpenter-craftsmen, particularly during the 1920 to 1939 period. The third is in the organization of construction around a general building contractor who specialized in church building, and preferred the use of pre-cut materials that reinforced a regular architectural style. The fourth is the emergence of more individual architectural practices and forms, influenced by modernist and western European conventions.

Early Church Painting in Saskatchewan

22 The same research material reveals a parallel, and in some ways complementary, history of the people who painted the interiors of these Prairie churches. Along with Lipinski in Alberta, the two Winnipeg-based painter-craftsmen Jacob Maydanyk and Hnat Sych are well known.14 Saskatchewan has supported several painter-craftsmen, one of the most significant being Paul Zabalotny.

Display large image of Table 2

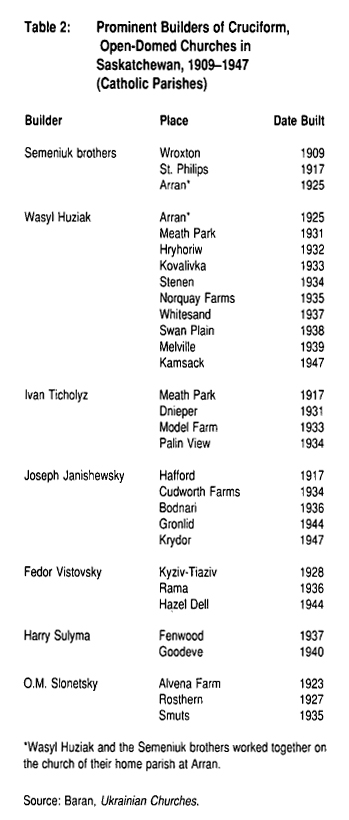

Display large image of Table 223 An important part of Ukrainian material culture is the aesthetic decoration of objects found in everyday life. Women were embroiderers, egg painters, floral arrangers and food sculptors; men were woodcarvers, carpenters and painters; both had a sense for patterns, especially with geometric and floral motifs. As an ongoing communal project, the church was decorated with the same attention to detail as were domestic objects. In church decoration, a unifying aesthetic was found in religious icons that had patterns of placement and subject, but allowed for the artist's individual style. Decoration of prairie Ukrainian churches was not a formal obligation, but rather a combination of aesthetic sense and social etiquette.

24 The development of church painting and the prominence of a few painter-craftsmen parallel in time and social significance the rise of carpenter-craftsmen as builders of churches. The respective precursors nonetheless seem different in structure, for the carpenter-craftsmen were preceded by folk builders, and the painter-craftsmen by commercially produced icons from western Europe. It seems that a confluence of European and Canadian historical trends in the decades around the turn of the century produced Ukrainian church painting on a hitherto unseen scale. There was increasing unity of Ukrainian cultural articulation in Europe, and the colonizing Ukrainians of the Canadian Prairies were soon enveloped by this metropolitan trend. Also, the relative affluence of Ukrainians in Canada allowed them to acquire the forms emanating from the cultural centres of Ukraine.

25 The parallel rise of carpenters and painter-craftsmen was in many ways harmonious. Both eschewed restrictive regionalism that might have made their forms incompatible to one another. A synthesis arose of carpenters who left a standard assemblage of interior surfaces, and painters who learned standards of treating those same architectural spaces. Their common inspiration tended to be the traditional Kievan style, as best as they could recall and apply it.

26 Painters in Canada took their work seriously, striving for a standard arrangement of iconic subjects. Their efforts were mitigated by the wishes of parishioners, who requested certain subjects, or favoured a painter on such criteria as a preference for one painter's stencil patterns.15 Painters could not generally make a living decorating churches, and would find work as house painters among the congregations which hired them.

27 There were complex undercurrents in the relationship between the painter and the parishioner. In an era when itinerants were viewed with a trace of condescension and indulgence by sedentary parishioners, some painters cultivated a puckish persona.16 Although their advice was sought on subject matter and their decorative skills were in demand, painter-craftsmen held a separate place in the community's social order. The painter was perhaps more sophisticated than the parishioner in his cultural expression, but the parishioner was in a position to employ the painter. A congregation's status was affirmed not only by its acquisition of metropolitan decorative forms, but also by its ability to hire a reputable craftsman to do the job. A painter's reputation in inter-war prairie Ukrainian society did not rest entirely on his ability as an artist. Contemporary informants remember whether a painter worked alone, or was businesslike enough to hire a crew in the manner of a general building contractor. Jacob Maydanyk, for example, is remembered not only as a painter, but also as a shrewd entrepreneur.

28 The painter and carpenter-craftsman offered similar expertise and fulfilled similar social roles. Although both craftsmen worked within Ukrainian styles, each contributed to the demise of regional folk styles by their knowledge of and control over desirable metropolitan styles. Their ability to establish widely known personal reputations in an esteemed specialist occupation devalued the broadly practised folk arts, which harboured regional traditions.

29 These craftsmen and the social significance of their work have stood between subsequent observers and the study of preceding folk traditions of architecture. Of the seventy-six generally folk-built churches raised between 1902 and 1919 in Saskatchewan Catholic parishes, no fewer than fifty-five were destroyed and replaced by carpenter-craftsmen by 1959 (table 1). The function of these craftsmen in popularizing a unified Ukrainian culture has deflected interest from the diversity of regional styles which the pioneers brought with them. Occasionally, however, the carpenter-craftsmen failed in their attempts to combine a personal touch with appropriate references to Kievan modes, producing work that can only be described as eclectic. An example is the well-known church at Dobrowody, Saskatchewan, an architectural uncertainty that was transformed into a national treasure by the brushes of Paul Zabalotny.

30 Table 3 shows the period during which church painting became popular and the rate at which painted churches became the general experience of Ukrainian worshippers. In 1929, only one in twenty-two congregations had hired a painter-craftsman, while, a generation later, one church in three displayed formal painting. More than a dozen church painters are recorded in Saskatchewan, but only two achieved prominence as painter-craftsmen in the manner of Peter Lipinski, Hnat Sych and Jacob Maydanyk. Stephan Meush, whose craft extended to woodworking, decorated the interiors of at least eleven churches from 1933 to about 1942 (table 4). Paul Zabalotny, who was active from 1930 to about 1955, painted at least twenty churches (table 5). Church painting was continued by Theodore Baran of Saskatoon, who worked on at least thirty-seven churches from 1950 to 1976, painting in the "true Byzantine tradition."17

31 The painting of Paul Zabalotny, over about twenty-five years, shows a gradual progression away from a folk aesthetic sense. Certain aspects of his work remain continuous, such as his standard placement of icons on the iconostasis and walls, and his preference for a central icon inside the dome. At Dobrowody (1936) he painted a few stylized logos (including angels and the Ukrainian trident) that were neither icon nor linear stencil, which became a prominent feature of his later work at Goodeve (n.d., built 1940), Alvena (1945) and Kuroki (n.d., built 1952).

32 The clearest evidence that Zabalotny was influenced by formal metropolitan styles is in his rendering of linear border stencils and the stencil-like patterns with which he framed his icons. His early stencils are similar to traditional geometric Ukrainian embroidery patterns, and are seen at Canora (1930), Dobrowody, Rama (n.d., built 1937), Goodeve and Kuroki. This aesthetic style is overridden by the appearance of bold, tendril-like abstract patterns with which he framed his wall and pendentive icons and which are similar in style to his symbolic logos. An early inclination toward this style is found in the floral designs around the pendentive icons at Rama and occurs regularly in the frames around the wall and drum icons at Alvena, Alvena Farm parish (n.d., built 1923) and Kuroki.

33 Both geometric and floral motifs are common in other traditional Ukrainian expressive media. What is remarkable is the sense of abstraction and modern boldness which affected floral designs in the church painting craft. Paul Zabalotny's adoption of bold floral patterns in the 1940s was a stylistic link to the artist-painter Theodore Baran. In fact, the icon frames at St. George's Catholic Church at Melville, attributed to Theodore Baran,18 are the same as those developed by Zabalotny at Alvena, Alvena Farm and Kuroki, creating a problem of identification. More important, however, is the change in aesthetic sense exhibited by Zabalotny, and the social changes reflected in his adoption of a more abstract, yet also traditional Byzantine style.

Conclusion

34 In Zabalotny's style of painting, in the popularity of church painting in general and in the architecture of the period, one sees a shift away from regional forms toward metropolitan Ukrainian forms of expression. A distinction is implied between the culture of the regional Ukrainian folk and that of the metropolitan Ukrainian nation. As prairie Ukrainian society modernized, it was most cognitive of metropolitan Ukrainian cultural leadership.

35 On the other hand, the techniques and organization of church building showed an acceptance of Canadian capitalist culture. The use of pre-cut lumber and commercial products instead of hewn timber and handcrafted features changed and reduced the work of parishioners during church building. The individualism and concentration that characterized the church carpenter and painter crafts of the 1920s are evidence of the changes in Ukrainian colonist society.

36 Interpretation of other aspects of church material culture gives further complexity to the experience of modernization in a migrant peasant society. The female home-based embroiderer tradition remained vital and retained many regional forms. On the other hand, the male home-based tradition of working wood to make religious objects largely disappeared. Commercially available wood products certainly reduced the need for woodworking, but the increasing capitalist consumption of manual labour also reduced general male productivity in the home and parish, the traditional loci of ethnicity.

37 Church architecture, a highly visible example of prairie Ukrainian culture of the 1920s and 1930s, points to the unfolding of a Ukrainian national consciousness from diverse regional heritages. At the same time, the increasing specialization of the carpenters' and painter-craftsmen's work represents a change in the meaning and division of labour for communal projects. The contrasting fates of the embroidering and woodworking aesthetic crafts illustrate the complexity of ethnicity, metropolitanism and modernity within Prairie Ukrainian society.