Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Contemporary Ukrainian-Canadian Grave Markers in Urban Southern Ontario

1 In contrast to the extensive analyses of older, rural graveyards, the modern tombstone and urban cemetery have largely been ignored as a source of study.1 The presumed anonymity and banality of modern graveyard "art" may, in part, explain the paucity of studies. This lacunae is unfortunate. Today, as in the past, the ceremony and art accorded the deceased have as much to say about the living as the dead. Indeed, the choice of material, the symbols selected, the placing and cost of the memorial, and the associated rituals and traditions of remembrance are tied inextricably to the status and identity of the family and community of the deceased.

2 This preliminary study examines contemporary Ukrainain-Canadian grave markers. The study is based on fieldwork conducted in four urban cemeteries in the Toronto-Hamilton area, namely, Prospect and York cemeteries in Toronto and Woodlawn and Holy Sepulchre cemeteries in Hamilton. The Ukrainian-Canadian memorials in these cemeteries are examined in themselves and in relationship to the older, rural prairie grave-sites predating the technological developments of the funerary and grave-making business. The symbols used and the very form of the grave markers are a unique expression of both personal and communal or ethnic identities.

3 The graves and grave markers of the Ukrainian-Canadian prairie settlements point consistently to the centrality of regional and religious identity. In an unpredictable world, religious rites provided indispensable succour to the peasant settlers. The tenacity with which these older religious and folk customs were retained is manifest in the organization of the church graveyard and in the selection of memorial symbols and inscriptions.2

4 As in the Old World, the location of the graveyard was not a matter taken lightly. The cemetery was holy ground, the place where the body of the deceased, the duly inducted member of the Church (Orthodox or Catholic), was placed in anticipation of the Second Coming. The cemetery grounds were blessed and sanctified and the plot itself accorded ritual blessings. Though now bereft of spirit and corruptive, the body was still of God, deserving not only the respect of the living but the appropriate ground in which to await final resurrection.

5 The cemetery itself was not a barren place. Ukrainian settlers believed in the persistence of the spirit, unsettled and hovering in the liminal time between death and final rest. However, in the joining of traditional beliefs and Christian orthodoxy, the cemetery was the sacred space, appropriately consecrated, where the dead huddled together, ideally near the church. By virtue of its proximity to the church, its sanctification as holy ground and the Orthodox/Catholic theology of the interrelationship of the living and the dead, the cemetery was a place of prayer and of congregation.3

6 The iron, wooden and cement crosses marking the burial plots stand as the physical emblems of sacred space. The cross itself, pointing to the grave as the locus of Christian burial, served as a personal identity marker of the deceased. To a certain extent it also served as an expository object of communal belief and identity. Painted or engraved on the cross were a variety of symbols and images expressive of religious belief, folk custom and regional derivation. Among the symbols are five- and six-pointed stars or star-like floral designs encased in a circle; three-barred crosses with the crescent moon at their base; a miniature box church at the foot of a cross; the IC and XC symbolic inscriptions: the Communion Cup; and various Passion symbols (the objects of torture appended to the cross).4 These images are not merely decorations but pietistic expressions in which the represented is realized in the depiction,5 or at least points to its realization for the deceased (the attainment of celestial paradise; the joyful consequences of membership in the Church; the victory of the cross over death and other enemies). Along with the religious symbols are the symbols and markings of regional identity—coloured glass or pebbles on Bukovynian burial mounds; a Muslim crescent for those whose folk legacy included Christian victory over Islam. Beyond the religious and regional identity of the deceased, the crosses convey only the barest of information—the name of the deceased, birth date, death date and village of origin. From a religious purview more than this was not required. Individuality is subsumed in a greater communal identity, both earthly—as a member of a village—and heavenly—in the confirmation of resurrection and eternal life.

7 Though the modern burial plot has certain obvious elements in common with these older gravesites, there are major differences in the conception and use of space and in the meaning of symbols.

8 In Catholic and Orthodox ritual, the cemetery is still regarded as a sacred space. A brochure for St. Michael's cemetery explains:

In the non-sectarian cemeteries, the Catholic or Orthodox plot itself—as distinct from the cemetery as a whole—is regarded as sacred space (upon performance of the appropriate ritual). The Ukrainian celebration of Green Sunday and other cemetery-based ceremonials are premised, in part, on these theological foundations, especially on the interrelationship of the living and the dead—more to the point, on the incorporation of the living and dead into the transcendent Body of Christ.7 On a more popular level, the celebration of Green Sunday may have less to do with theological complexities than with the remnant celebration of seasonal cycles of rebirth, the popular legacy of post-death needs (the presentation of food and drink for the deceased) and tradition.

9 Though these ceremonies are still performed in urban Ontario, their location (however sacred) is very different from the older gravesite. As the internment literature from Hamilton and Toronto points out, their cemeteries are operated not only as places of internment and reflection, but also as "gardens of beauty and interest for the living."8 The trustees of the Toronto General Burying Grounds, for instance, pride themselves on the acquisition "over a period of many years [of] an extensive collection of rare and unusual trees, shrubs, evergreens and herbaceous plants...which combine with the native species to form botanical gardens which probably comprise the broadest range of such plants to be found in the Toronto area."9

10 Because of these aesthetic considerations, as well as health and safety reasons, the rules and regulations of these cemeteries are explicit in barring materials and funerary addenda present in older gravesites: "Mounds will not be permitted over graves";10 "No tablet or monument or other structure composed in whole or in part of wood or iron is permitted";11 "All headstones shall be made of granite, marble or other durable material and no artificial stones will be permitted";12 "Borders, fences, railings, walls, cut-stone copings and hedges in or around lots become unsightly and are prohibited";13 "Wooden or wire trellises will not be allowed in cemeteries and any stand, holder, vase or other receptacle for flowers or plants that may be deemed unsuitable or unsightly may be removed."14 The overall purpose of these rules and regulations is to maintain "the dignity and decorum" of the lawn cemetery.15

11 Within the constriction of these rules, the modern Ukrainian burial plot is little different from any other ethnic or native plot—except for the variety and range of symbols and images impressed on the memorial. Three types of symbols and images can be distinguished: the universal; the specifically Ukrainian; and the idiosyncratic mix of the two.

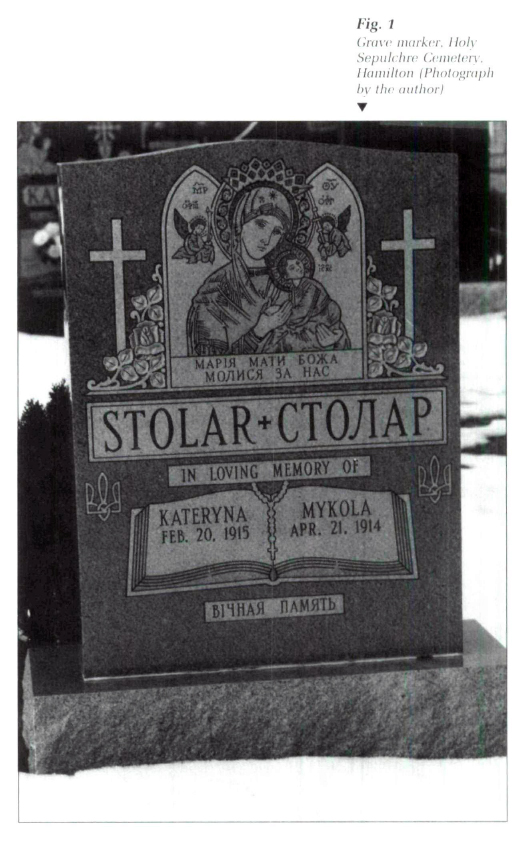

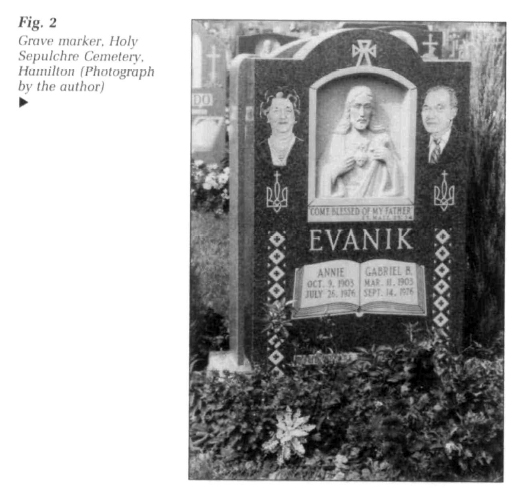

12 The universal designs comprise the commonplace symbols and images that no longer have a specific ethnic or distinctive character, but have become the collective property of Western funerary art. Among the more prevalent of these designs are the multitude of floral images—roses, chrysanthemums, lilies—and the ubiquitous "open book." While the open book may have once been a rendering of the Bible within the specific domain of Protestant Anglo-Saxon communities, the image today serves as the "document" upon which the name, birth date and death date of the deceased are recorded; the image has come to mean simply the "book of life."16 With the technological advances in memorial craftsmanship (allowing for clear and detailed imaging), newer forms of universal images have made their appearance on memorials. Among the more interesting of these are the religious icons of popular piety. Renditions of DaVinci's "Last Supper," Michelangelo's "Pieta," the Good Shepherd and the praying Christ at Gethsemene have become commonplace. Among Catholics, the image of the Sacred Heart is especially popular. Though these images are not strictly "universal," they seem to transcend all cultural lines among the Christian faithful; their mass appeal may be due partly to their pathos and their mass depiction—especially the Last Supper and the Pieta—on everything from wall hangings to dishware.

13 However commonplace these symbols and images may be, it would be a mistake to assume they are merely decorative or perfunctory. Nicholas Neu, a Hamilton memorial craftsman, pointed out that the selection of images and inscriptions is not lightly made. A newly widowed woman, for example, had requested that he inscribe something completely different from the "usual" on her husband's memorial. After rejecting a number of common epitaphs, she finally settled on "In Loving Memory." She felt that the epitaph reflected her sentiments perfectly. And so, unknown to an observer of her husband's memorial, the simple epitaph inscribed has a personal meaning belying its ostensible commonness.17

14 Of the specifically Ukrainian symbols and images, only a few of the older designs are found in southern Ontario. I have yet to locate any crosses with the crescent moon appended or any of the star-like designs that appear to be legion in the older prairie cemeteries. Their absence in the cemeteries of southern Ontario may have Less to do with regional differences than with the diminished relevance of the symbols (the Muslim association of the crescent has been replaced in recent times, no doubt, by the spectre of contemporary political enemies).

15 Among the more prominent of Ukrainian symbols and images in the cemeteries of southern Ontario are the trident; the Orthodox triple-barred cross: various configurations of wheal sheaves, kalyna berries (cranberries) and a panoply of embroidery designs; the Madonna of Perpetual Help and other icons of the Virgin; as well as Cyrillic inscriptions—not simply as conveyors of information but as distinctive, linguistic marks of identity and "filial" duty.18

16 The trident—the symbol of Ukrainian nationalism—is depicted in a variety of shapes and associations: alone: capped with the cross (most commonly) as an expression of both national and Christian identity: appended with swords and the cross commemorating the burial of a Ukrainian veteran; enlaced around the fleur-de-lis of the Ukrainian Boy Scouts movement. The importance of the trident is immediately evident. Not only is it displayed prominently in the centre or on opposing sides of many memorials; it is also emblazoned in gold as a particular mark of national identity.

17 The Orthodox triple-barred cross has in recent years become more than the historic property of the Orthodox Church. A very Latinate Christ in a Prospect cemetery memorial is depicted hanging from a large Orthodox cross. The general "Ukrainianization" of the Orthodox cross is not restricted solely to cemeteries. Apparently, as Reverend Roman Danylak of Toronto (Catholic Ukrainian) has noted. Catholic and Orthodox Ukrainian-Canadians alike have begun wealing triple-barred crosses not only as expressions of faith but as visible emblems of their ethnic identity.19

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 118 Though not exclusively Ukrainian, the wheat sheaf and certain floral design (the kalyna berries and the lily in particular) are fairly common symbols on Ukrainian memorials. In religious symbolism, flowers have traditionally indicated "the beauties and pleasure of paradise"; the lily has been emblematic of "special purity"; and wheat, of resurrection.20 On the more popular level, the wheat sheaf has come also to represent the Ukrainian nation in its association with the earth and the golden harvest emblazoned on the Ukrainian flag.21

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 219 The ubiquitious embroidered patterns on Ukrainian memorials—though varying in design—are only ostensibly different from each other. While a very few individuals select embroidery patterns for their specific regional or historical relevance, many Ukrainians, as Roman Demkiw, a Toronto memorial retailer points out, choose their designs on purely aesthetic grounds from the list of "Ukrainian" patterns available. The importance of the memorial embroideries is not only aesthetic but avowedly ethnic. The aesthetic import is in the decorative appeal of the design, and the ethnic import in the enduring statement being made of "Ukrainianness."22

20 The Byzantine Madonna of Perpetual Help is an especially prominent image on memorials at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Hamilton. This and other icons of the Virgin dot the various cemeteries under discussion. The Madonna of Perpetual Help, though originally a Western Catholic image, has become a central funerary icon of Ukrainian Catholics. Its prevalence may he explained, in part, by the influence of the Madonna as intercessor and by the powerful symbols associated with the (depicted in Byzantine style).23 Surrounding the icon of the Virgin and Child are Cyrillic inscriptions for Maria Regina, Queen of Heaven, Archangel Michael, Archangel Gabriel and Jesus Christ (quite a panoply of protectors). The presence of the image in holy cards, distributed at funeral parlours and churches, is an important component of its popularity.24 The recurrence of the icon in the cemetery itself has spurred others to follow suit in their selection of funerary images.25

21 While all these symbols and images can he found separately, they are more commonly mixed in idiosyncratic arrangements (depending on cost and the memorial space available). Universal symbols—most commonly, the book of life (or scrolls) and floral designs—are mixed with Ukrainian or Ukrainianized elements—the trident most prominently along with wheat sheaves and embroidery designs. The juxtaposition of and addenda to these elements point to an extraordinary variety of personal expressions on the part of modern Ukrainian Canadians unknown or simply unimportant in the past. Circles and hearts are intertwined with tridents and crosses: sun rays rush from one end of the memorial to the other: the Last Supper is bordered with "Ukrainian" embroidery: photographs or engravings of the deceased are placed in juxtaposition to icons. What is one to read in all of this?

22 In contrast to the older markers, the variety of funerary expression has allowed modern Ukrainians to choose, far more than ever before, what they wish remembered about themselves personally and communally. Grave markers contain a relative profusion of personal information, not only name, birth date and death date, but also photographs (in porcelain medallions), engravings, associational memberships, military record and so forth. The choice of expensive black stone (difficult to obtain in Ukraine) is further evidence of the importance of status and keeping up with the expectations of the burial norms of a community, of doing "the right thing."26 The memoria is not simply the physical placemark of burial but a public statement of individual identity and achievement. Of course, such a statement is by no means an exclusively Ukrainian trait. In the modern world, this orientation is due to the interplay of conspicuous consumption, the dread of death and the obsession, accordingly, with the perpetuation of a known image (notwithstanding the ostensibly transcendent religious symbolism on memorials).

23 Besides the emphasis on individuality, the memorials point to a communal identity that, unlike the older memorials, is less sub-regionally specific than assertively and homogeneously "Ukrainian." The general Ukrainian embroidery, the Byzantine icons, the trident and the wheat sheaf assert the commonality of all the Ukrainians buried in any given cemetery. The recent foundation of the St. Vladimir Cemetery near Oakville, Ontario, has brought this sense of nationalism to the fore; in recent years, Catholics and Orthodox alike have been exhumed from various cemetery sites throughout the region and reburied at St. Vladimir's. For a people whose homeland is occupied, the emphasis on a generalized communal sensibility transcending Old World regional and religious lines is understandable. The irony is that the greater the effort to assert and portray general Ukrainianness, the more homogeneous that identity becomes; the more self-conscious the statement of nationalism—a statement expressed in a set range of symbols—the more sanitized and created it becomes. This is not to say that the contemporary sense of national identity is any less authentic or vital than subregional identification in the past. In fact, quite the contrary. The memorial is an important and final statement of identity; the seeming homogeneity of Ukrainianness is simply an expression of contemporary reality.