Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Ukrainian Grave Markers in East-Central Alberta

1 There are many more traditional rural Ukrainian-Canadian graveyards in east-central Alberta than there are studies dealing with them.1 The Ukrainian proverb "zhyvyi zhyve hadaie" ("a live person thinks of live things") is probably the best explanation for this state of affairs. On the other hand, as R.B. Klymasz demonstrated in the documentary film Luchak's Easter, a cemetery can be a lively place.2 Although one could attempt to find a single representative Ukrainian-Canadian prairie graveyard in east-central Alberta, it is probably more prudent to deal with three types of this aspect of Ukrainian-Canadian material culture to reflect the historical dominance of the three religious denominations (of the traditional Eastern or Byzantine rite) to which Ukrainian settlers in Canada belong.3

2 One of the oldest Ukrainian burial grounds in east-central Alberta is at Skaro (near Bruderheim) just north of Highway 45 (some seventy kilometres northeast of Edmonton). It is an excellent example of jurisdictional differences, as about two-thirds of the cemetery belong to the Greek Catholic Parish of the Holy and Lifegiving Cross and the remaining third to the Russian-Orthodox Parish of the Holy Ascension.4 Another pioneer graveyard is that of St. Mary's Ukrainian Orthodox Parish at Szypenitz near Hairy Hill (again, north of Highway 45). This cemetery originally came under Russian-Orthodox jurisdiction. Here, however, the community decided to switch from Russian to Ukrainian orthodoxy. Although many Ukrainian pioneer cemeteries in Alberta could have served to demonstrate; the religious material culture of Ukrainian settlers, the two cemeteries at Skaro and the Szypenitz graveyard constitute a representative sample.

Common Features

3 Certain aspects of Ukrainian religious material culture occur in all three graveyards: head-stone or marker forms; ornamentation; the language of inscriptions; and viability or upkeep of the burial grounds.

4 The earliest forms of markers used in pioneer graveyards were wooden crosses, of which only remnants can be found today. The demise of the wooden marker was not only due to gradual deterioration but was also hastened during the annual spring cleaning; remnants of the previous year's wilted turf and under-brush were burned, destroying many a wooden marker.5

Display large image of Figure 1

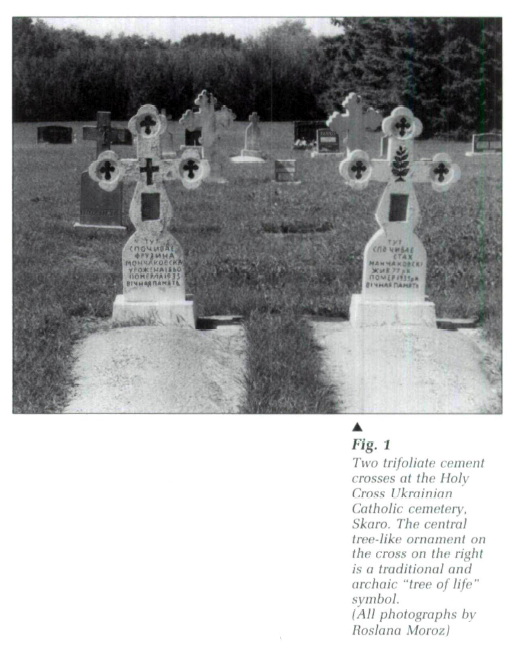

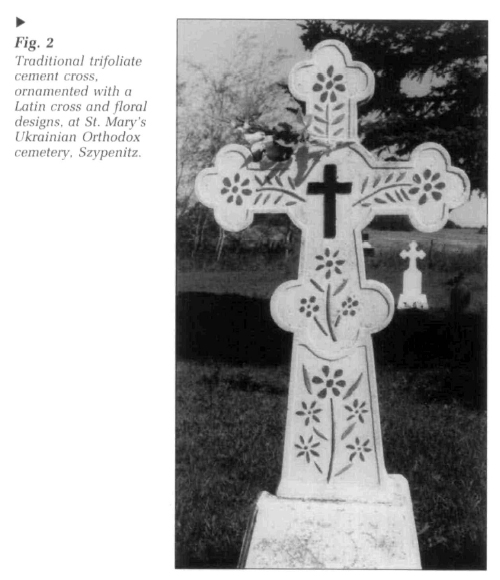

Display large image of Figure 15 The most common grave-marker form found in the burial grounds of each of the three religious denominations is the trifoliate or botonée cross (figs. 1 and 2).6 These trifoliate cement markers were poured into forms supported by crossed metal bars. They continued to be placed in the cemeteries as late as the 1950s.

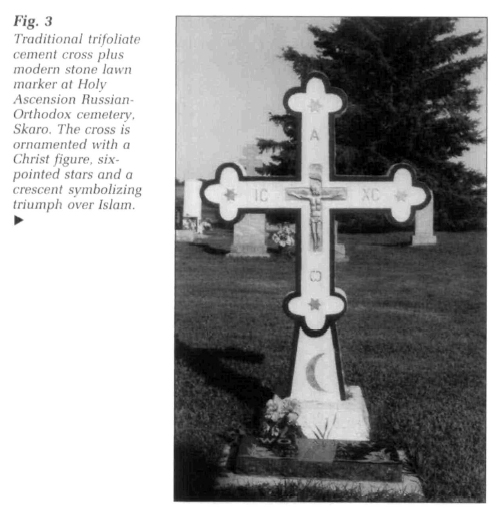

6 Another feature common to Ukrainian-Canadian cemeteries is the decoration on the burial markers, usually executed in relief. Although not as pervasive as the cement markers, these ornamentations are frequently encountered. Images with the oldest historical roots include five- and six-pointed stars and floral symbols. Some of the older plant-shaped symbols may even he related to the cosmogonie "tree of life." Crosses of various forms are often used as ornamental and symbolic signs in the central part or on the arms of cross-shaped markers. The symbol of the victory of Christianity over Islam is a crescent at the foot of some crosses (fig. 3). The relief of Christ hanging on the cross is characteristic of Western spiritual tradition. Such reliefs are more in be expected at Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery, but can be found on gravemarkers in the two Orthodox graveyards as well.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 37 Christian symbolism is also found in the inscriptions on the markers. Abbreviations come somewhere in the middle between ornamentation and inscriptions. The letters "IC," "XC," "A" and "Ω" standing for "Jesus," "Christ," "the Beginning" and "the End," are the most common abbreviations on the markers (see fig. 3).

8 Ukrainian is the language used in main of the inscriptions in all three graveyards. Bilingual (Ukrainian and English) inscriptions appear on some headstones, and others are English only. Personal names sometimes appear in Ukrainian and English versions. In one instance, the metal plate attached to the back of the headstone gives the vital statistics of the deceased almost identically in both Ukrainian and English, the English version having additional information on the time and port of entry into Canada as well as the man's homestead section. Inscriptions exclusively in English can be found on markers of more recent origin.

9 The efforts of successive generations of Ukrainian pioneer stock to join and keep up with mainstream Canadian society are reflected in the decreasing maintenance of these graveyards, in both physical upkeep and viability. As smaller family farms become a thing of the past and the prairie population moves to the cities, the future of rural cemeteries comes into question. Recent graves, new headstones and discussion with local inhabitants confirm that burials of individuals with strong local ties still take place in these cemeteries, albeit less often.

Differences

10 Just as there are common denominators indicating shared culture, so are there two issues clearly differentiating the three graveyards. One of these differences reflects the formal religious denominations and the other, language.

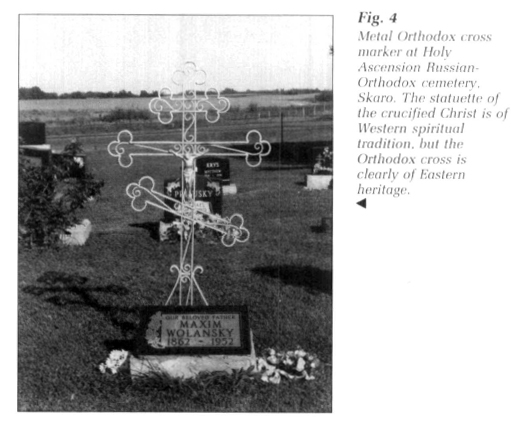

11 The religious division between the Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic denominations is clearly demonstrated by later cement and stone markers. What shall be termed here the "Orthodox cross" is distinctly recognizable as part of the headstone, the form of the marker itself, a decoration over the grave marker (see fig 4) or even a decoration on the grave mound in the two Orthodox burial grounds.7 Latin-style crosses and symbolism have the same function at the Ukrainian Catholic cemetery. Of course, this Catholic-Orthodox dichotomy is not without exceptions. Some markers within Orthodox graveyards reflect the typology of Western Christianity, and vice versa.8

12 The linguistic differentiation is not as clear cut as that of the cross types. Old Church Slavic used to be the lingua franca of official church services at the time of Ukrainian-Canadian pioneer settlements. Ukrainian became the official language of the newly formed Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church of Canada, though St. Mary's Parish did not officially switch to Ukrainian Orthodoxy until 1941.9 The Ukrainian Greek Catholics used Old Church Slavic in official church services until the late 1960s, when they switched to Ukrainian. (Ukrainian had always been used as the vernacular among Ukrainian Catholics during sermons and other non-official activities.) In Russian Orthodox communities, Old Church Slavic is still the Language of official services. The language of the community seems to have been Ukrainian with an admixture of Russian. This variety of language use can be observed in some of the headstone inscriptions.

Other Considerations

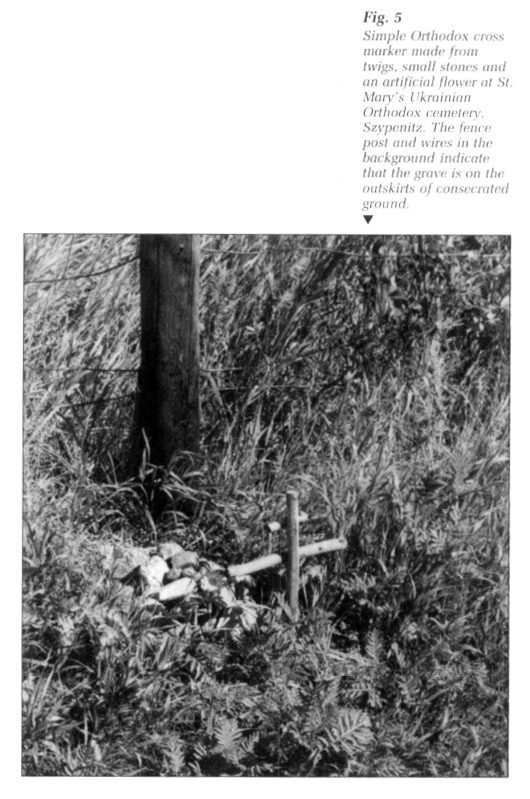

13 Many more characteristics of the three graveyards could be explored. Some individual grave sites warrant further research: For example, what brought about the belated attaching of the metal plate on the marker noted earlier? Originally, the stone was not elaborately inscribed, but the metal plate includes not only the personal information on the deceased, but also contemporary Soviet administrative territorial terminology and even a spelling correction of the surname. A monument at St. Mary's cemetery worth further investigation is the chapel-style marker on the Mehara family plot; a certificate of service in the army of the Austrian Emperor Franz-Joseph is visible through a glass window in the door of the chapel. Nearby, a diminutive Orthodox cross made of twigs stands beside a little pile of pebbles with an artificial flower at the southeastern fence of St. Mary's cemetery (fig. 5), reflecting ecclesiastic and community rules that applied to the burial of suicidal deaths, rules that were once strictly applied.10

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 514 In other instances, individual or group language loss seems to be partially compensated by some ornamental symbol of ethnic identity, such as the neo-traditional geometric "cross-stitch" design. And even modern markers sometimes reflect traditional sex roles, as is clearly the case in the depiction of knitting needles and a ball of yarn on one side of a spousal grave marker, and a convertible automobile on the other.11

15 This brief investigation into some aspects of Ukrainian-Canadian grave markers in east-central Alberta indicates that Ukrainian cemeteries are important sources of information for researchers of material culture as well as of local history. It is hoped that the recent designation of St. Mary's churchyard, including its cemetery, as a provincial historic site will encourage further studies.12