Reviews / Comptes rendus

Francess G. Halpenny, ed., Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. VI, 1821 to 1835

1 Volume six of the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, which was released in April 1987, contains the biographies of 479 individuals who died during the period 1821-35. Like the previous nine volumes, this one reveals as much about the writing of history in Canada as it does about its subjects. When the first volume appeared in 1966, Canadian history was almost exclusively focused on the politically and economically powerful. Since then it has enlarged its scope to include many social groups and the activities not only of workers, social reformers and women, but also athletes, criminals, artisans, Indians, gardeners and cooks. Naturally this change has involved the use of diverse new sources and methodologies. The background of the authors and their scholarly formation have also evolved.

2 Change in the perception of Canada's past has not been restricted to formal or academic history; over the same period a broad public interest has developed in "heritage," or the history of ordinary people, such as genealogy, the post office, antiques, the military, and heritage buildings. This populist movement has been varied, mostly materialistic and often nostalgic. One of its results has been the appearance of many books of increasing sophistication on antique furniture, glass, lamps, tools, toys, pottery, and silver. This enlargement of the scope of society studied by history and the new public interest in the past, or at least objects of the past, have conjoined with the efforts of material historians, largely museum based, to elaborate the interaction of material objects and society.

3 Given these trends during the past generation, one might ask about the extent to which material history has been used in the most recent volume of DCB. The volume has biographies by 283 authors with diverse perspectives (see pp. 861-68) so one might expect that some would have used material objects in their biographies. However, nothing in the 32-page bibliography (pp. 827-58) suggests that any such source has been used for any of the biographies. The bibliography is divided into five categories. The first two, "Archival Sources" and "Printed Primary Sources," and to some extent the third, "Reference Works," are primary sources. There is no indication that any collection of material objects, or indeed anything other than the written word, was used in any of the biographies. Two museums are listed, but only their manuscript collections and not their holdings of artifacts are given as sources. The last two parts of the bibliography are for secondary sources and no obvious reference to books or articles about artifacts of any description appear in them. Perhaps this is a result of traditional biographic methods; perhaps it is an indication that material objects go unmentioned in the biographies. Let us see.

4 The "Index of Identifications" on pages 870-85, which is predominantly a listing of the biographies by 25 occupational groups, offers another prospect of finding material history in the volume. Many of the occupations, such as inventors, engineers, doctors, or labourers and labour organizers, used tools or worked in a object-rich environment. For others—architects, artisans, and artists—their goal was to produce objects, and so it is difficult to see how their lives can be assessed without reference to such things. Forty-eight entries, 47 men and one woman, appear in these three latter occupations, and artists are further subdivided into four categories. Four men are listed more than once; François Baillairgé is under sculpture, painting, and architecture. There are then a total of 43 individuals, or about nine percent of the biographies in the volume, involved in these three occupations. One can reasonably expect some revelation about the place of material history in Canadian historical writing in the mid-1980s from this selection of entries.

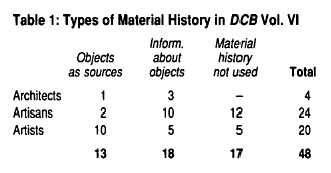

5 Generally speaking material history can take one of two forms, either the history of material objects or the use of material objects as sources for social history. Examples of the first would include the establishment of provenance for specific objects and, as well, accounts of the changes in the creation and use of categories of material objects, such as tools. Examples of objects used as sources to document human events are unusual in "history," but relatively common in art history and the norm in archaeology. In biographies, such as these in volume six, specific objects associated with an individual might prove to be useful "documents." Each of the 43 biographies were reviewed for their two types of material history: objects as sources for human history, and objects as the subjects of study. A third possibility, of course, is for material history not to be used in the biography. Since the 43 individuals had 48 different occupations, the biographies were reviewed for their material content under all 48 activities. The results of this analysis are shown in table 1.

6 As can be seen, roughly an equal number of the biographies fit into each of the three categories. However, significant differences exist for architects and artisans on the one hand and for artists on the other. Art historians used objects as a historical source in 50 percent of their biographies, while the products of artisans were used only eight percent of the time as documents. Architects are between these two extremes, although the sample is very small. Similarly, all but a quarter of the biographies of artists mention material products, while only half of the biographies of artisans do. These differences, and perhaps their causes, can be made clearer by examining the accounts of the men in each of the three occupations.

Architects

7 The biographies of all four architects— François Baillairgé, John Cannon, John Merrick and James O'Donnell—provide considerable information about building construction in the first quarter of the last century. Architects were less dominant then than they were later and thus attribution of particular buildings to them is often uncertain. Cannon's biography (pp. 119-21) reveals considerable detail about his materials, his houses and his work. At times, the detail is so extensive that it seems to reveal the man's character, but the sources are more archival than three dimensional. The account of Merrick (pp. 500-501) approaches the question of what credit, if any, he should get for the design of Province House in Halifax. His skills and the building's characteristics are compared, but his role in creating this and other buildings is unclear. O'Donnell put great energy and time into overseeing the construction of Notre-Dame in Montréal. However neither that church, nor any other of his buildings, are used as a source for the biography, although accounts and plans, perhaps indirectly from secondary sources, are used.

8 The biography of François Baillairgé uses his surviving architectural work, as well as plans for buildings now gone, to assess his ability, his relationship to owners and builders, his interpretation of Quebec architecture and his impact on succeeding architects. Baillairgé, alone among the 43 individuals, had three occupations. In all three, the authors have used material evidence to establish the man's work, character and place in Quebec's architectural and artistic history. It may be that this level of analysis is possible only because of earlier work on the history and attribution of existing material culture in Quebec.

Artisans

9 The social rank of artisans has meant that relatively few documentary sources of their lives have survived. Accordingly, material sources should be even more critical in assessing their lives. In practice, however, this source is not used. Of the 24 artisans in volume six, no information is given about the material production of twelve. Ten of the biographies contain information on the material output of the men's lives. In only two cases are the material remains of the artisans' careers used to help explain their lives. In part this limited use flows from the difficulty of relating specific artifacts to an individual's life. Yet it should be possible to use a particular craft's surviving tools and products to make generalized statements about conditions of works, skills and technology.

10 This missed opportunity is brought into focus by some of the ten biographies of artisans who were journalists, printers or publishers. Their work has often survived and is mentioned and even discussed in some of their biographies. Nevertheless, no biographer has tried to use the quality of the paper, the type font or the layout of these publications as an indication of the artisan's market, wealth or values. The newspapers of Francis Collins are used as a source, but only for their printed information not for their material information (see pp. 164-66). Similarly, the material characteristics of the thousand broadsides and newspapers of Bartimus Ferguson (see pp. 92, 247-49) are not used as a source for his biography. Most of the printers' and publishers' biographies do not mention their work and do not contain any material history.

11 Of the twelve artisans whose biographies ignore material history, the occupations of four are only incidental to their story. Cornelius Albertson Burley, Charles French, James Owen McCarthy and Henry Sovereene are included because they were convicted murderers. Their biographies focus not on their work, but on their crimes, trials and deaths. McCarthy was killed in a prison brawl, the other three were hanged. Burley's biography (pp. 91-93) is a good example, and it also includes an extraordinary piece of information which incidentally might constitute material history—the only example in these four biographies. After his execution, Burley's body was given to doctors for dissection. They severed his head and gave it to a phrenologist who displayed it the day following the hanging. Then the top half was cut off and kept. The bottom half was found in 1960 and is now displayed in Elden House, a London, Ontario, museum. This bit of material history says nothing about Burley, of course, but perhaps something of his society.

12 In the biographies of the ten artisans, information about the material circumstances of the individual's life is given that could be useful to material historians. An example is Anthony Henry Holland (p. 322), a papermaker, whose newsprint was dried with a special wall. He also built the first paper-mill in Atlantic Canada. Similarly Charles Jourdain (p. 366) was an industrial mason, and his biography includes considerable detail about a mason's work. The accounts of John Cannon and John Merrick, who were both artisans as well as architects, provide information about their work, houses and construction materials. In the biographies of Hugh Christopher Thomson and Pierre-Edouard Desbarats (p. 191-92), and in many others, the individual's house, which could be used as an indication of wealth and social position, is mentioned but not related to the subject's work or life. In the case of Andrew White (p. 812), whose rise in social rank from artisan to businessman is the principal feature of his life, the statement is made that "the comfort of his social position is reflected in his ownership of a cottage on the Rivière Saint-Pierre at Montreal." This sentence and biography would certainly be useful to anyone writing the history of that house. However, is his ownership of the cottage used as evidence of his social position? Perhaps. If the sentence (and presumably the thought) were reversed it definitely would be.

13 The material production of an artisan's life is used as evidence in at least two instances. The biography of Benjamin Chappell includes considerable excellent information about his craft. A statement similar in structure to the one quoted above is made: "More sophisticated society required new gadgets, and after 1801 he built coaches and sleighs for several leading Charlottetown figures." Like the claim about Andrew White's cottage it is difficult to decide whether information related to objects reflects some social reality. In this biography Chappell's creations pervaded his life, and his life's work is integrated into his character. Thus the products of his work revealed and explained his character. The account of Louis Quévillion, who was both an artisan and an artist, uses his wood carving as evidence of his activities. The biography of John Howe does not fit into any of these categories. He made a major effort in his life to be unmaterialistic and to the extent that he was successful no material history can be written about him. Perhaps the analysis of his life's effort to avoid materialism is itself a form of material history.

Artists

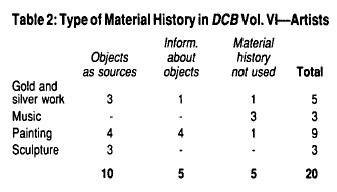

14 The artists are subdivided into four groups in the "Index of Identification," and although they are treated as a single group in table 1, it is useful to break them into their specific occupations in considering the material history in their biographies. The same criteria given for table 1 are applied to these 20 artists.

15 Music is the only anomaly among the artists. Unlike the other three occupation types, the end of their art was not the creation of an object. Thus the prospects for material history are marginal.

16 Gold and silver workers in Canada almost always signed their work and as well some of their work frequently survives. Accordingly, it can be used, and is used, in their biographies. Charles Duval's one surviving piece of silver is cited with reference to his character (see p. 227); Soloman Marion's silver is employed as evidence, not only to judge the man, but also to confirm archival sources. The last sentence about James Orkney (p. 557) refers to a piece of his silver as proof of his partnership with Joseph Sasseville. The silver of Benjamin Etter is assessed, but is only casually linked to the man. Only in the case of Dominique Rousseau (pp. 663-67) is a silversmith's work not part of his biography—for the simple reason that no work appears to have survived. This absence is a pity because the biography draws upon sophisticated computer analyses of notarial contracts and is written by one of Canada's finest historians of silversmiths.

17 Although silversmiths are considered artisans by some, the same cannot be said about painters and sculptors. They and their work are clearly part of art history. Some of their biographies, such as those of Joseph Brown Comingo (pp. 168-69), Peter Rindisbacher (pp. 648-69) and François Baillairgé integrate the man's work into his biography. One, that of Sir George Bulteel Fisher (pp. 256-57), provides a detailed history of his painting, so much so that the man himself is almost overshadowed. The work of Elizabeth Frances (Hale) Amherst is not used as a source for her life or otherwise treated as material history, but her painting is assessed in detail. Others, such as that of Robert Hood (p. 327) and Robert Pilkington (p. 583), assess the men's paintings but not as historical sources. Only the biography of Henry Parkyns Hoppner, however, completely ignores material evidence. As can be seen in table 2, in the biographies of all three sculptors the artist's work is used as a historical source. The artistic legacy of Louis Quévillion (p. 625) even reveals partnerships and social relations.

Conclusion

18 Bibliographical methods rarely accommodate the effective citation of material history evidence, or for that matter such archival documentation as photographs, films and maps. The bibliography in this volume fails to indicate that material evidence was ever employed as a source. Yet in the selection of 43 relevant biographies, objects contributed data in about one quarter of the cases and information on objects was contained in over one third. Forty percent of the biographers ignored material history completely. Reference to material history was more common with the work of artists than with artisans and architects. A major reason for the difference may stem from the tendency of artists, as defined by the DCB, to sign their work, while artisans did not. Clearly, however, material historians have more work to do to have their historical approach reflected in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. They can promote their field by completing more historical studies or even by compiling lists of surviving artifacts, including possible attributions, for individuals or occupational groups. With more information the relationship between the individuals and material culture will be easier to establish. Having said this, one may still conclude that social historians and others have yet to use fully the opportunities material history has already opened for them.