Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Documenting Ukrainian-Canadian Churches in Alberta

1 Ukrainian-Canadian church architecture represents a distinct architectural style familiar to communities across Canada where Ukrainians have settled. In Alberta, Ukrainians established themselves in the Edna-Star district, subsequently moving east and west along the North Saskatchewan River to occupy an area known as the east-central bloc settlement. In this region of Alberta, more than seventy-five Ukrainian-Canadian churches built before 1950 are still in existence. However, as communities dwindle in size, many of these churches risk falling into disrepair and are threatened with demolition. In an effort to document Alberta's remaining Ukrainian churches, the Inventory Programme of the Historic Sites Service, Alberta Department of Culture and Multiculturalism, undertook a survey of the pre-1950 churches in east-central Alberta.1 The results of the study provide observations on the character of Ukrainian church development in Alberta.

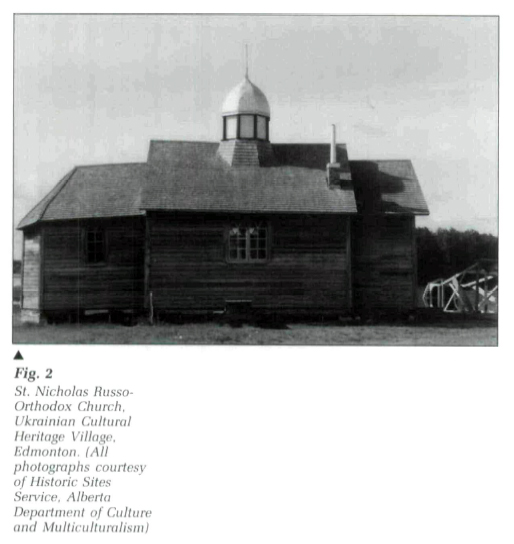

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 22 When Alberta's Ukrainian pioneers arrived, one of the first efforts of the communities was to build a church. The earliest Ukrainian churches were rudimentary structures illustrating the communities' level of economic prosperity and, to some degree, the availability of trained builders. As simple as these early structures may have been, they still satisfied the basic functional needs of the Byzantine rite.2 They always included a sanctuary and nave so a service could be conducted. In these early churches, as with the ones built later, basic liturgical requirements were met, with a view to maintaining a stylistic and symbolic link to Ukrainian antecedents. Ukrainian church architecture in Alberta clearly drew upon the rich architectural traditions of Ukraine. Historically, this tradition was based upon rural wooden church designs, western European sources and Byzantine elements to create a uniquely Ukrainian style. The study has shown that church styles Alberta are primarily based on Ukrainian wooden architectural traditions as well as larger, masonry-built Ukrainian baroque churches. However, an examination of this body of Ukrainian-Canadian church architecture clearly illustrates that indigenous trends emerged when architectural forms were transferred to new lands.

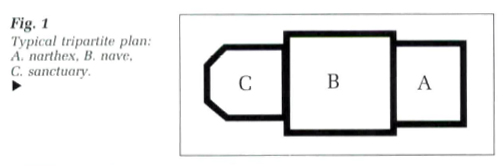

3 The fundamental spatial unit used in the building of wooden structures in Ukraine—a compositional element that influenced the plan of masonry churches as well—is described as the klit. The klit is generally a four-walled structure constructed of logs laid horizontally one atop the other; less commonly it is a six-or eight-walled structure, the corner ends fitted into position by a variety of interlocking techniques, one of which is zrub ("blockwork" or the "log-cabin style").3 As the dimensions of the log units, which approximate a square, depend on the lengths of timber used, they are rarely longer than 8 metres (about 26 feet) to a side, and most often measure between 5.5 and 6 metres (18 and 20 feet). Typically, the plans such wooden churches consist of three separate, solid timber units, formed in a three-part linear progression from narthex to nave to sanctuary. The central klit of this tripartite plan is normally broader and taller than the two smaller adjacent units on its east and west sides. The tripartite plan, the simplest of the church plans, was commonly reproduced in Alberta (fig. 1). Thirty-three of the extant seventy-five pre-1950 Ukrainian churches in east-central Alberta were built on the tripartite plan, most ol which were built before 1918.4

4 The St. Nicholas Russo-Orthodox Church, originally of Kiew, Alberta, and now relocated to the Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Village just outside Edmonton, was built between 1905 and 1909 (fig. 2). It is one of many tripartite churches that adhere closely to the wooden church models found in western Ukraine. Members of the Russo-Orthodox faith in Canada were predominantly Ukrainians, most of whom came from the historically Greek Orthodox region of Bukovyna.5 St. Nicholas displays the fundamental characteristics of the tripartite plan. The narthex and nave are covered by separate gable roofs, the narthex roof slightly lower than the broader, central nave. At the east end, the pentagonal apse is also covered by its own roof. A single blind dome or bania resting on an octagonal drum is centred on the nave roof, following the Ukrainian practice of placing the dome, when there is only one, on the central unit of the church. Most Greek Orthodox churches in Alberta were built along the traditional east-west axis, with the altar facing east, as the one in St. Nicholas church did when it was constructed.6 Also typical are the paired windows on the north and south sides of the nave.

5 Building techniques used in the construction of St. Nicholas are consistent with those found in western Ukraine. The foundation, for example, is built of rocks which prevent the wooden zrub from making contact with the ground.7 This technique was used in other Ukrainian churches in Alberta—such as those found in Waugh, Wostok and Smoky Lake—but concrete and masonry foundations were also common.8 The walls of St. Nicholas were of squared logs, preferred over split or rounded logs in the Carpathian mountain regions and many parts of Galicia.9 The interlocking corner joints were dovetailed and the logs were pinned together with wooden pegs throughout their lengths for greater stability.10 The builders of St. Nicholas not only adhered to traditional construction techniques, but also used the basic proportions of their European models. The 5.4-by-6-metre (about 17 by 20 feet) nave of the church is virtually identical to the 5.5-by-6-metre (about 18 by 20 feet) measurement traditionally found in the Carpathian regions.11

6 Ukrainian-Canadian church design shares with its European-Ukrainian predecessors the distinctive feature of a separate belltower. The development of a belltower detached from the body of the church can be traced back to the watchtowers that were a defensive element of most fortified towns and villages in Ukraine. As part of the fortification, the belltower was traditionally built using a timber frame, rather than a log-built zrub technique. This Ukrainian tradition is consistent with the belltowers that appear with Ukrainian-Canadian churches. The belltowers are generally square, clad with boards fitted vertically and capped by a second-storey covered or enclosed gallery where the bell is placed. In 1908, a simple "belltower" consisting of two horizontal logs set on posts was built west of the sanctuary of the St. Nicholas Russo-Orthodox Church,12 and a bell mounted on it. This effort to create the spirit of the belltower was modestly improved in 1911 and 1912 with the erection of four tall inclining timbers with a bell placed at their apex.13

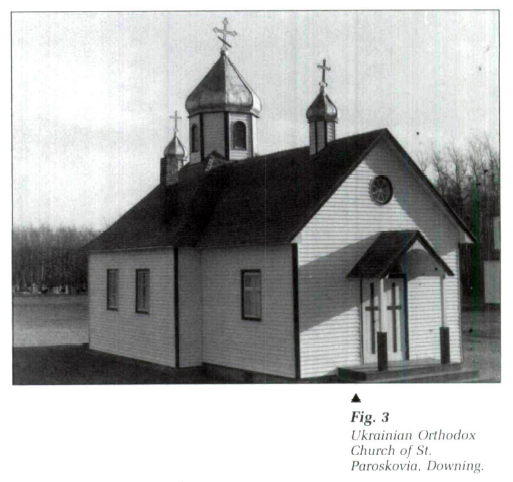

7 The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of St. Paroskovia, constructed between 1921 and 1924 in Downing (fig. 3), illustrates the visible similarities and subtle differences of the tripartite plan in Alberta. It boasts three small cupolas surmounted by a galvanized dome, one centred on each of the three units corresponding to narthex, nave and sanctuary. The paired north and south nave windows correspond in shape, size and placement to those found in wooden church designs in Ukraine. Continuity of tradition is also seen in the use of prominent overhanging eaves. Originally developed to protect walls and foundations from the heavy rains typical of the foothill regions of Ukraine, the broad eaves are a feature that, in Ukrainian-Canadian churches, was motivated by stylistic and traditional, rather than practical, concerns. Though convenient, wide eaves are hardly a necessity in Alberta, as they are in Ukraine.

8 The builder of the church of St. Paroskovia also incorporated an architectural element often found in Ukrainian-style wooden churches in Europe and Canada. The krylo or porch found on the west end of some churches may be supported by wooden columns or may simply be an unsupported hood over the door.

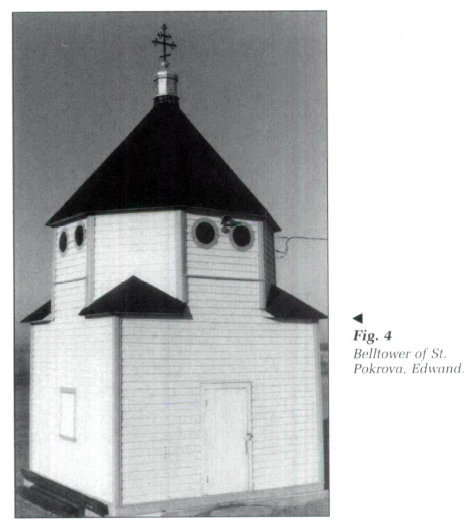

9 The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of St. Pokrova in Edwand, like St. Nicholas and St. Paroskovia, has a separate frame and clapboard belltowers. The tower adjacent to St. Pokrova reveals a further variation derived from Ukrainian sources (fig. 4), one seen in several Alberta churches. The second storey of this square tower is an octagon with a conical roof. The transition from a square base to an octagon results in tetrahedrons, referred to as "sails," at the four top corners of the square base.14

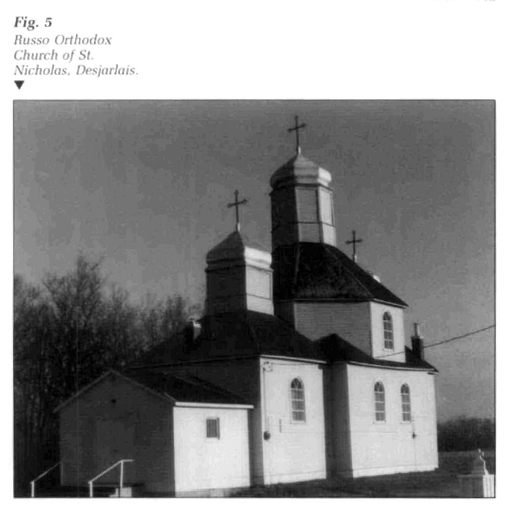

10 Within the tripartite church format, the octagonal klit on a square base is an architectural motif sometimes used in the construction of a broader central unit. It was often a hallmark of the Podillian School, which was particularly widespread in the regions of Podillia and Volhynia, both areas that border on Galician and Bukovynian ethnic territories.15 Sails again appear at the transition point from the square base to the octagonal drum. One example of this style is the Russo-Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas built in Desjarlais in 1917 (fig. 5). The octagonal central klit was technically more difficult to construct and more elaborate in its effect. The open octagonal extends the height ot the interior space while creating new and complex interior spatial dimensions, characteristic of Ukrainian baroque architecture. In addition, the towering central klit is capped by a blind dome placed on a tall octagonal drum, further delving the horizontally of the linear plan. When the second-tier central klit is used, it is generally pierced by a window centred above the pair of windows on the lower north and south nave walls. To further enhance the exterior decorative scheme, blind windows were built into the cupolas of some.

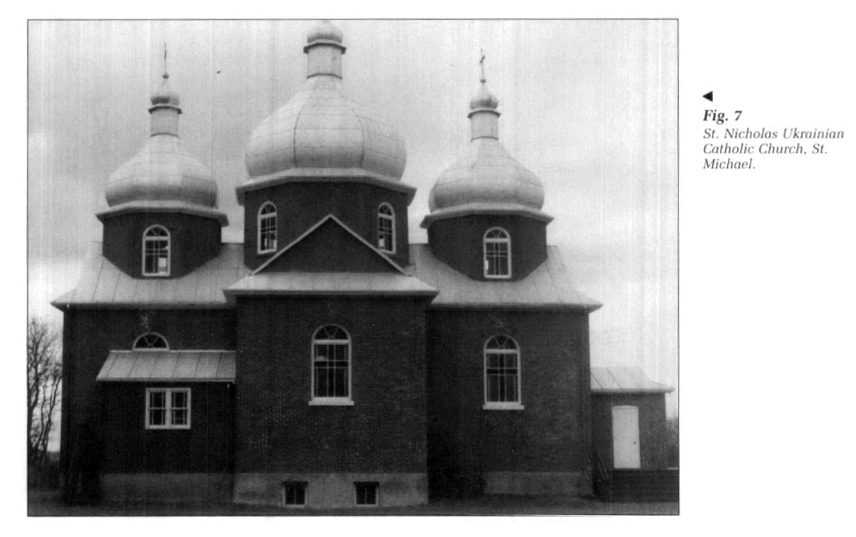

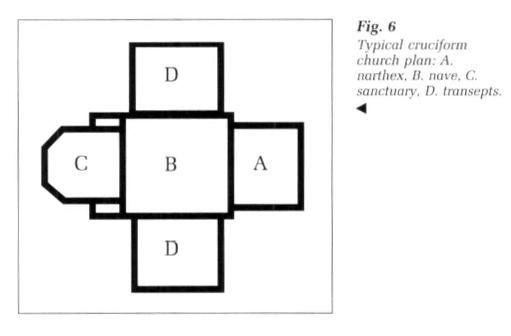

11 Many parishes outgrew their first churches fifteen to twenty years alter settlement of the area, due to the arrival of new Ukrainian immigrants. A growing population base allowed church executives to consider expansion of the existing structure or construction of a new church. Most parishes chose the latter option, and after 1909, the large five-part or cruciform church plan began to appear.16 Over half (thirty-nine) of the extant seventy-five pre-1950 Ukrainian churches in the study area were built on a cruciform plan. The five pail, or cruciform, church design consisted of the linear tripartite pattern with two octagonal or square units attached to the north and south sides of the central nave (fig. 6). The essential difference between the tripartite and cruciform plans is in the addition to those north and south arms. Concomitantly, an increase in the number of domes—up to nine—could embellish the grander architectural scheme.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 612 The cruciform plan is most prevalent in Volhynia and the Kiev and Hutsul regions of Ukraine, whereas churches based on the tripartite plan dominate Galicia and Bukovyna. Although Ukrainians in Canada are predominantly from the latter two regions, regional architectural styles in Ukraine were not necessarily confined to any given region.17 The relatively close proximity of the Hutsuls to the Bukovynians (the Hutsul region lies northwest of Bukovyna along the Carpathian mountain range) explains the assimilation of the five-part plan in that region. As well, many examples of Hutsul-style churches can also be cited throughout Galicia and the rest of the Carpathian region.18

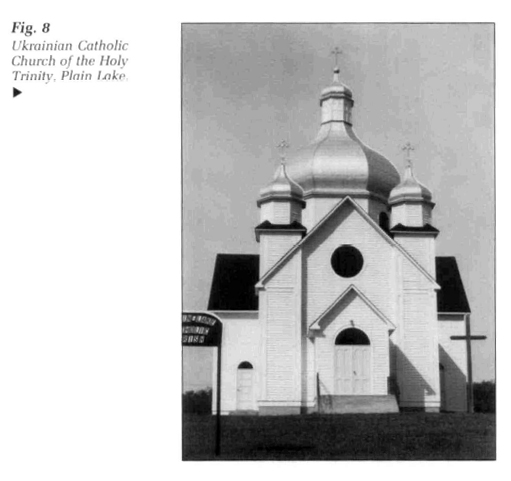

13 One feature of Ukrainian churches in Alberta is more difficult to trace back to origins in Ukraine. On either side of the entryway at the west end of both wooden and masonry (including frame and stucco) churches axe tall, narrow towers, usually capped by small domes. This motif is unquestionably linked to the influence of western European baroque architecture in Ukraine during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The curved and undulating facades and the twin-towered west fronts of baroque church architecture had a significant impact on Ukrainian masonry architecture. On the Canadian Prairies, however, the twin-tower motif assumes a unique form in many church designs, one that has no direct parallels in Ukraine. It can be seen in many Ukrainian-style churches in Alberta, such as the Ukrainian Catholic Church of the Holy Trinity in Plain Lake, built in 1926 (fig. 8).

14 A precedent for these facade towers can be traced to local French-Canadian church designs, which also attempted to reproduce in wood the classical baroque facades of Europe. Ukrainian Catholics had been advised by their own church authorities in the Old Country to accept the aid of the Canadian Roman Catholic Church until their own was organized and incorporated.19 In Alberta, French-Canadian Catholics were prominent in the organization of the Catholic church, the activities of which extended into rural areas. It is not surprising, therefore, that local French-Canadian architectural models found their way into Ukrainian church designs. Ukrainians, however, attached domes to the tops of their towers instead of the classicized French-Canadian clochers.

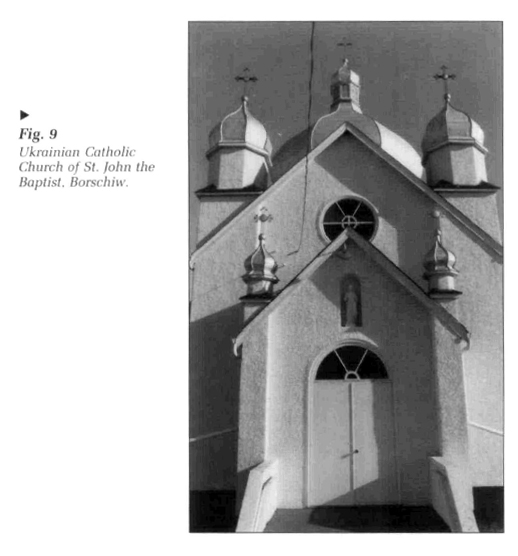

15 As Ukrainian communities became more established in Alberta in the 1930s, frame and stucco construction was often used by builders of Ukrainian churches. It was a technique that had few precedents in Ukraine, so builders often imitated the French-inspired, twin-tower, five-part churches developed by earlier Ukrainian Canadians. The Ukrainian Catholic Church of St. John the Baptist in Borschiw (fig. 9), constructed in 1939, is a large-scale, five-part frame and stucco design that illustrates the assimilation of the twin-tower motif. The builder freely interpreted the motif by adding another pair of smaller lowers to the enclosed porch. Consistent with most clapboard-sided churches, the stucco structures were while. Vertical members capping the corners of the wooden-sided churches were often painted in a contrasting colour, a device that emphasized the vertically of the church and clearly defined each architectural unit. This contrasting element was absent from the stucco-covered church.

16 Some of the Ukrainian churches in Alberta use a twin-tower motif that more closely approximates the proportions of Ukrainian baroque masonry architecture. St. John the Baptist Ukrainian Catholic Church, constructed in Lamont in 1947, and the Holy Trinity Ukrainian Orthodox church in Calmar built in 1927-28 are two examples of church designs modelled on the majestic baroque style. Both churches are of frame and stucco construction and are based on the cruciform plan. The towers of St. John the Baptist are much broader than those of other Ukrainian churches in Alberta. The towers are capped by tall cupolas of western European baroque design, a type frequently incorporated into Ukrainian baroque masonry churches. The bold towers and the unique placement of the five cupolas of Holy Trinity also suggest an attempt to imitate the characteristics of Ukrainian baroque masonry architecture. In wooden church architecture, domes were placed axially, but here the five large domes are placed on the diagonals of the church plan.20 The largest is centred on the nave end and the remaining four on the four corner towers, indicating that a stone church, not one of logs, was the architectural source.

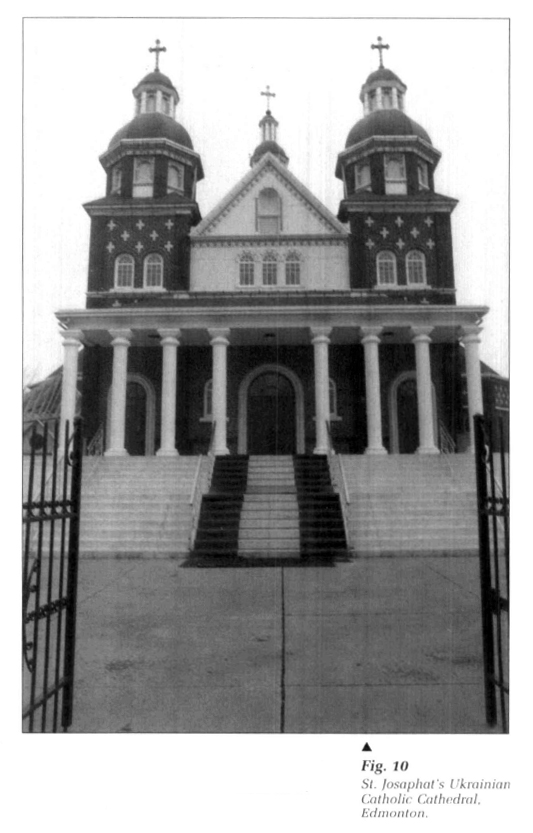

17 Perhaps the only church design in Alberta to capture the true spirit and splendour of Ukrainian baroque masonry architecture is the one executed by the Reverend Philip Ruh for St. Josaphat's Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral in Edmonton (fig. 10). Constructed between 1939 and 1944, the church is based on the largest of the Ukrainian baroque schemes, a nine-part plan with the addition of four smaller square units occupying the angles between the arms. Though the original plan called for ten domes, only seven were built (those on the north and south arms and over the sanctuary were eliminated). The west front portico, supported by eight Tuscan columns, is approached by a grand 9-metre (30-foot) wide staircase, a feature illustrating that the impact of the Italian baroque style in western regions of Ukraine was not overlooked by Ruh. St. Josaphat's is the product of a skilled architect, unlike those constructed by local builders in main rural communities in Alberta. Ruh's professional training and financial backing allowed him to focus on more ambitious architectural schemes of Ukrainian origin. He managed to convex a sense of historical continuity within a Ukrainian architectural tradition. Yet, like many wooden churches in Alberta's rural communities, St. Josaphat's is not a slavish copy of a church in Ukraine,

18 Ukrainian church architecture represents a significant measure of the cultural landscape in Alberta. These churches are vital and living reminders of the connection between the old and the new, and of the way Ukrainians have shaped the land to reflect their heritage. The systematic documentation of pre-1950 Ukrainian churches in Alberta was the first of its kind in the province. With the aid of a growing body of photographic records and historical data, a greater awareness of the specific contribution of a local Ukrainian architectural tradition is possible. Such a heightened understanding of these sites will govern the identification of significant churches and lead to their preservation in the future.