Conference Reports / Rapports de colloque

VI International Congress of Maritime Museums

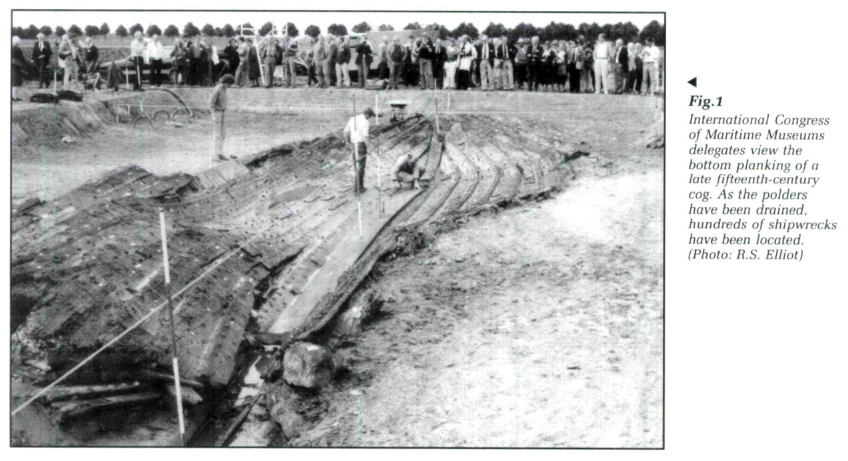

1 Few conferences offer participants as varied a fare as that which was presented last year at the sixth triennial meeting of the International Congress of Maritime Museums. Along with a full slate of informative lectures, our Dutch hosts provided an impressive array of extracurricular activities tailored to please those with an interest in nautical subjects. Over a period of one week, conference delegates examined the planking of a late fifteenth-century European cog, stood on the massive ribs of a replica Dutch East Indiaman and felt the pulse of the world's busiest port-Rotterdam. However, for those who are not familiar with the International Congress of Maritime Museums, a brief outline of the organization's history and aims is, perhaps, the best preface to a review of the 1987 gathering.

2 The International Congress of Maritime Museums (ICMM) is merely a youngster compared with so many other museum organizations throughout the world. The organization's start can be traced to a meeting in 1969 at Mystic, Connecticut.1 It was in Mystic that Waldo Johnston, director of the Mystic Seaport Museum, and Basil Greenhill, director of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, expressed an earnest desire "to found an international professional group to represent maritime museums."2 Those present were in agreement and it was proposed that an international conference be staged at Greenwich in 1972.

3 Every three years, since that first international conference at Greenwich, there have been meetings at which museum professionals have gathered to exchange ideas, share research and report on developments of their respective institutions. The second conference took place in 1975 at the Norsk Sjøfarts-museum in Oslo; the Mystic Seaport Museum played host in 1978 and the Musée de la Marine in Paris organized the 1981 gathering. Delegates at the fifth conference met in Hamburg at the Museum fur Hamburgische Geschichte and travelled to Bremerhaven and Lubeck for additional sessions.

4 The published proceedings of the first five conferences reveal the varied interests of the organization's membership. While an interest in maritime topics is the obvious link, presentations range from discussions concerning underwater archaeology to the restoration of vessels, the role of marine museums and display techniques. The range of interests represented at the sixth was no exception.

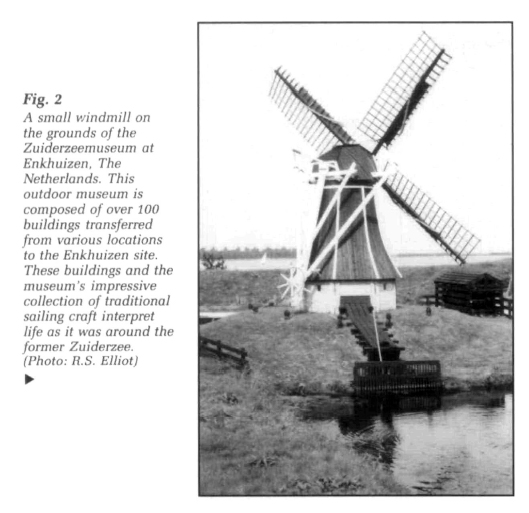

5 The first day, 5 September, delegates embarked from Amsterdam for the city of Enkhuizen for an opportunity to tour the Zuiderzeemuseum. This complex, composed of both indoor and outdoor components, offers visitors an overview of life as it once was along the shore of the former Zuiderzee. Entire buildings have been transported to the site and reassembled to create a village atmosphere. While a connection with the sea (the lifeblood of the Netherlands) is clearly evident, other occupational pursuits are also represented throughout the 130 structures. The presentation of a social history is a clear and stated goal of the outdoor museum which re-creates the living and working conditions of the villagers from 1880 to 1930. Given the outstanding quality of the outdoor complex, it is not at all surprising that the open-air museum at Enkhuizen, which opened in 1981, has quickly become a major public attraction.

6 The first lecture session covered several topics concerning the maritime heritage of the Low Countries—an introduction to the maritime history, archival resources, marine museums and the preservation of traditional sailing craft. An overview of the maritime history of the Low Countries traced Dutch marine activities and development to the present and served as a fitting introduction for delegates. The archival presentation indicated the resources available to the researcher, but also cited problems that historians face the world over. Certain important collections do not have indexes to assist in the location of research material and documents are widely scattered; in particular, modern government records are often still held by the relevant ministry. However, for this reviewer, the closing statement of the archives lecture held the most meaning when the speaker expressed the "hope that this is the beginning of an era of more fruitful cooperation between maritime historians and maritime museums."

7 Though the main theme of the third presentation was an abridged look at the maritime museums and collections of the Low Countries, the documentary value of objects was stressed. This must have struck a familiar chord for many in the audience, especially for those conducting material history research.

8 The final, and perhaps most intriguing, presentation of the first session was one that revealed the prominent role that private initiative has played in the preservation of traditional Dutch sailing craft. Such private sector intervention has led to the survival of hundreds of sailing barges and fishing boats without government aid. Even though these efforts have not received official support, Dutch museums, helping to preserve a tradition, have been able to assist through providing information on restoration and through publishing material on certain projects.

9 Two full sessions examined the importance of shipwrecks to historical research and maritime museums, as well as problems arising from wreck finds. Though it was stated that the discovery of certain wrecks has stimulated the development of some maritime institutions, one thought-provoking presentation dealt with the problematical relationship between private salvors and marine museums. Citing the fact that wrecks can contain unlimited wealth in historical information, if properly excavated using archaeological methods, the speaker questioned the ethics of accepting privately salvaged artifacts. The desire to make another acquisition must not encourage the destruction of knowledge by amateurish retrieval methods. In the same light, the curator must weigh carefully the benefits of acquisition against the problems of conservation, for the very elements that have led to the preservation of wreck materials leaves the same vulnerable to deterioration once brought ashore. It was suggested that in many instances, a detailed archaeological survey might be preferable to the actual recovery of a wreck.

10 The presentation by Canadian marine archaeologist Robert Grenier provided insight to the investigative methods being employed at Red Bay, Labrador. Archaeologists have been raising the timbers of Basque whaling vessels, gathering research data and returning the excavated material to the original site for reburial. Beyond the benefit of restoring the artifacts to their original context for possible re-excavation in the future, the alternative to raising a wreck makes economic sense. Conservation facilities are in short supply and preservation treatments are time consuming and costly.

11 One of the "shipwreck" papers explained the building of late medieval cogs (the freight carriers of northwest Europe) which gave conference participants some background knowledge when a cog excavation site was visited later that same day (8 September). A presentation on experimental archaeology—the construction and launching of a Greek trireme (an Athenian warship of the fifth to fourth centuries B.C.) proved fascinating because the reconstruction was not based on actual excavated remains. Experiments have been conducted with this reproduction to confirm the historical validity of the design and to determine the seaworthiness, speed and manoeuvrability of the vessel. Answers to these questions help to shed light upon the trireme's use by the Athenian navy and the vessel's effectiveness as an instrument of war.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 Session four and five included papers which covered a variety of topics. Presentations showed how maritime museum development projects, such as the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool, have had an important impact upon the regeneration of unused harbour-front docks and warehouses. The problems associated with the acquisition and maintenance of large port machinery were discussed and plans for the development of Sydney Harbour (Australia) presented. Several lectures addressed the roles of marine museums in academic research and the dissemination of maritime culture and information. Data retrieval in Dutch maritime museums and public access to museum information by means of computer and video disc also offered the audience ideas for the application of these new technologies.

13 Several papers of the sixth and final session of the 1987 congress looked closely at ethical considerations in ship model conservation and restoration. It was stressed that these models deserve the same application of accepted conservation principles as other museum artifacts in order to preserve their historical integrity. All too often ship models are subjected to "improvements" for display purposes and invaluable technical information is lost. One speaker suggested that it is often preferable to produce a replica for display and to leave a particular model in its damaged or altered state. It was also noted that a danger of misinterpretation can be created when ship models are exhibited in a context for which they were never intended. The example cited was of an "inaccurate" votive model being used to illustrate a certain vessel type.

14 In short, the sixth International Congress of Maritime Museums was a profitable experience where one had an excellent selection of informative, thought-provoking lectures and the opportunity to discuss mutual problems with colleagues from around the globe. Information transfer and the dissemination of developed solutions to common problems should be the goals of any conference. In this sense, the 1987 gathering in Holland certainly proved successful. If at all possible, delegate attendance at these triennial meetings of maritime museum professionals should be considered a priority by any serious marine institution.

15 For information on membership in the International Congress of Maritime Museums contact: Richard M. Holdsworth, Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust, The Old Payoffice, Church Lane, Chatham, Kent ME4 4TE, United Kingdom.