Articles

A Heritage Lost:

The Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, 1927-1983

This paper describes the circumstances surrounding the construction, lifetime and demolition of an unusual Manitoba Ukrainian Catholic church. Using parish records, newspapers and oral history resources, the author traces the steps taken by the Ukrainian Catholic pioneer community of Portage la Prairie in the 1920s to create and sustain a large frame church. The parishioners of the Church of the Assumption built an impressive Byzantine "prairie cathedral" under the supervision of the Reverend Phillip Ruh, relying on volunteer labour and resources. These factors and their limited means led to the construction of an edifice that was beautiful but structurally flawed. Deterioration of the shell occurred over the years, exacerbated by insufficient maintenance. In the 1970s the decision was made to build a new church. The city's demand for off-street parking, the Manitoba government's lack of an appropriate heritage-preservation policy, and the parish's and community's failure to appreciate the church's value as a historic monument all contributed to the destruction of a landmark.

Résumé

Cet article décrit les circonstances entourant la construction, la fréquentation et la démolition d'une église catholique ukrainienne tout à fait particulière au Manitoba. Grâce aux registres de la paroisse, aux journaux et à la tradition orale, l'auteur retrace les efforts d'une collectivité de pionniers ukrainiens catholiques pour ériger et conserver une grande église à ossature de bois à Portage la Prairie, dans les années 1920. Sous la direction du révérend Phillip Ruh, les paroissiens de l'église de l'Assomption ont fourni gracieusement temps et matériaux pour bâtir une véritable «cathédrale des Prairies» de style byzantin.

Compte tenu de ces facteurs et des moyens limités dont ils disposaient, les paroissiens ont construit un bâtiment splendide, mais dont la structure était compromise par des vices de construction. L'enveloppe s'est détériorée au fil des ans, d'autant plus que l'entretien a été négligé. Dans les années 1970, il a été décidé de construire une nouvelle église. Étant donné que la municipalité exigeait un stationnement, que le gouvernement n'avait pas institué de politique adéquate pour préserver le patrimoine et que la paroisse et la communauté n'ont pas su reconnaître la valeur historique de l'église, un véritable monument a été détruit.

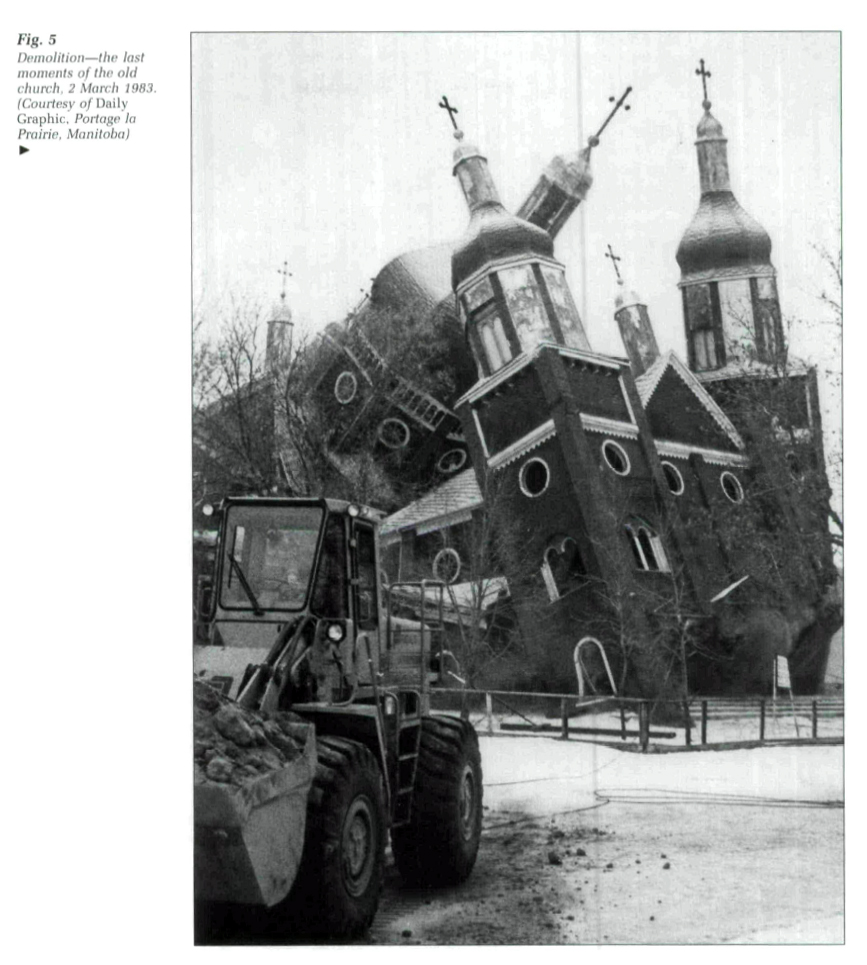

1 On 4 September 1927, the cornerstone of the new Ukrainian Catholic Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Portage la Prairie was ceremoniously blessed at a service attended by many people, including the local MP and MLA. In his speech, the mayor of the city, W.H. Burns, thanked the parishioners "for the beautiful edifice they had erected at such sacrifice, which would be a memorial for all time."1 Unfortunately, this promise was not to be fulfilled. On 2 March 1983, on what the Ukrainian Voice called "A Sad Day in the History of Manitoba's Ukrainians,"2 the church that had been a landmark for over half a century was demolished.

In the Beginning

2 Drawn by the prospect of cheap land on the Prairies, Ukrainian peasants from the Austrian provinces of Galicia and Bukovyna began immigrating to Canada in large numbers in the mid-1890s. Not all settled on the land. Some chose to stay in Portage la Prairie, which just after the turn of the century was a thriving town of about 4,000 people served by the Canadian Pacific, Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk Pacific railways. Ukrainian men could find work in the railway yards and shops and in the small manufacturing and construction companies. Ukrainian immigrants settled in the north end of the town, close to the railway tracks, the foundry and the brick-works, where housing was cheap.3

3 Ukrainian Catholics built their first church between 1905 and 1907. It was a small frame structure 40 feet by 20 feet (12 m by 6 m), built with volunteer labour on land donated by one of them. At that time the community had only fifteen families, but it grew quickly, and the church soon became too small. Even though they were usually without a resident parish priest, the parishioners decided in early 1919 to start collecting money for the construction of a new church.4 Consideration was given in 1920 to buying a church building from a Roman Catholic parish, but nothing came of this project.5 After further delays, a twelve-man building committee was selected in April 1923. This committee, in the presence of Bishop Budka, the Ukrainian Catholic bishop for Canada, was shown some plans by a church builder, one Tycholis. They liked his design of the church at Keld, Manitoba, but a year later there was still only talk, this time of a church 72 feet by 20 feet (22 m by 6 m) that was to cost no more than $8,500.6 Nevertheless, a plot on which to build appears to have been purchased in 1924,7 and by early 1925 the building fund stood at $3,129.20.8

4 In August 1925 the parish's cantor, George Michalchyshyn, was elected to the executive committee of the parish council.9 He began to play a leading role on the building committee, which appears to have been restructured at about the same time. It was probably shortly after this that Bishop Budka suggested to Michalchyshyn that the committee contact the Reverend Phillip Ruh, an Oblate priest who had embraced the Byzantine rite. Ruh was then just completing the first of his large prairie churches—later often called his "prairie cathedrals"—at Mountain Road, Manitoba. Father Ruh met with members of the parish, who told him, after some deliberation, that they wanted a wooden church capable of seating 200 people.10

5 So a momentous partnership was begun. Some construction materials were obtained in 1925, but "owing to circumstances it was not possible to commence building operations until 1926."11 By this time the parish consisted of about a hundred families. Most of the heads of families were wage-earning employees of the railways, but their work was primarily seasonal; probably only fifteen or twenty had steady full-time work. By the time the construction of the new church began, some parishioners, alarmed by the delays, were asking to have their donations returned, while others had suspended their giving.12 These were not happy omens. Nonetheless, about $4,000 was on hand when the building began.13

6 Living as they did on a "cash on the line" basis, the parishioners were initially heartened by information given them by Father Ruh. They would save money, he said, if they built the church themselves, as had been done at Mountain Road. They need only build when they had money; when they ran out of money, they could suspend building to raise more funds.14 Clearly, this mode of operation could put the congregation into a precarious financial situation; it also could, and did, lead the builders into the temptation of using lower quality materials. For the success of the construction under these circumstances, much depended on community interest in the project, individual generosity and selflessness. Father Ruh and George Michalchyshyn set an example in selflessness by agreeing to have payment of their salaries deferred throughout the course of the church's construction; one of the carpenters, M. Sawchuk, later did likewise.15

7 There can be no doubt that the cost of the church, at over $25,000, greatly exceeded the congregation's expectations. To the $4,000 with which they began, they succeeded in adding a further $18,000 between 1926 and 1930. Fund-raising events took the form of bazaars, bake sales, teas, picnics, raffles and games of chance. Much of the money was raised by the parish's women's auxiliary, whose role was never properly acknowledged.16 There were also, of course, individual donations, sometimes at critical moments, as when the lumber firm refused to supply further wood on credit; one of the parishioners, Kyrillo Stroch, sold his cow for $40 (to the great dismay of his wife) and gave the money to the church.17 Despite all the collections, donations and sacrifices, there remained a debt of $2,320, mainly in the form of the deferred payments; neither Rub nor Michalchyshyn had been paid as of 1944, and it is doubtful if they ever received the money due them.18

8 Such problems, however, still lay far in the future when work began on the foundations of the new church. In the initial stages of construction, Father Ruh relied on himself and volunteer labour for the day-to-day work. The basement was dug using horses pulling "scrapes" to do the heaviest work; men, women and children hauled the earth away in wheelbarrows.19 Ruh was tireless. Not himself a trained architect, he tried to makeup what he lacked in expertise with enthusiasm, dedication and sheer hard work. "He was there every day, from early in the morning till late at night, doing everything, even breaking rock with a sledge hammer."20

9 Ruh did not yet have much experience in constructing buildings suitable for the climatic and soil conditions of Manitoba. But he had a good designer's eye. Under his supervision and with his eager participation the concrete for the basement foundations was poured, and the shell of the structure speedily began to rise. The lumber underpinnings were mostly 2 inches by 8 inches (5 cm by 20 cm), with some 2 inches by 10 inches (5 cm by 25 cm). Insufficient provision was made for ventilation. Construction of the walls, roof, towers, ceiling and windows was similarly flawed. Moreover, the best materials—the most expensive and most sturdy—were in the basement. As money became more of a problem, the building was constructed of increasingly inferior materials.21

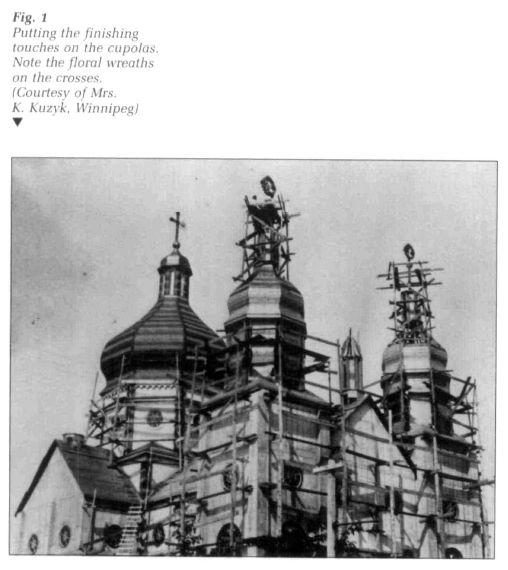

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 110 As the full magnitude of the structure became apparent in early 1927, some parishioners became faint-hearted. "What does be think he's building, Rome?" they asked. Ruh was certainly building on a grand scale. Fearful of debt and other unknown consequences, some of the congregation deserted the parish— probably about thirty or forty of the hundred families who had started the project. Funding became even more of a problem. Rather than suspend building, the remaining parishioners steeled themselves to raise more money and complete the task before them. Pride, determination and the need for a new church (the older one having been demolished in 1926) spurred them on. "Volunteers came by the dozen: as long as you could hold a hammer and as long as you could see what you were doing with the saw, you had a job there—all voluntary. There wasn't a cent paid."22

11 By the summer of 1927 the roof was up. On 24 July two crosses were blessed and erected, with Father Ruh explaining the symbolism of the ceremony.23 On 4 September the cornerstone was laid and blessed to denote the completion of the main work on the structure.24 Although all the work on the interior remained to be done, and many details of the exterior too, the church was operational in 1927.25

12 Although the main structural work had been completed with the use of voluntary labour, two carpenters who had earlier worked with Father Ruh at Mountain Road were hired in June 1927. These maistry (masters) were to be paid $4.50 a day, and every member of the parish was to board them for three days each. In 1928 a painter, Kyrylo Sych from Winnipeg, was hired to paint the interior and exterior of the church, at a total fee of $4,000. This large sum was evidently also to cover Sych's expenses, such as payments to his helpers and the costs of his materials.27 Of course, there was continued reliance on volunteers. Because of the intricacies of the work, and probably because of financial problems, it was not until 1930 that the last details were completed. On 20 July 1930, on what the Portage newspaper termed a red-letter day for the Ukrainian Catholic parish, the final consecration service was held, with a pontifical mass celebrated by Bishop Ladyka, recently appointed Ukrainian Catholic bishop for Canada.28

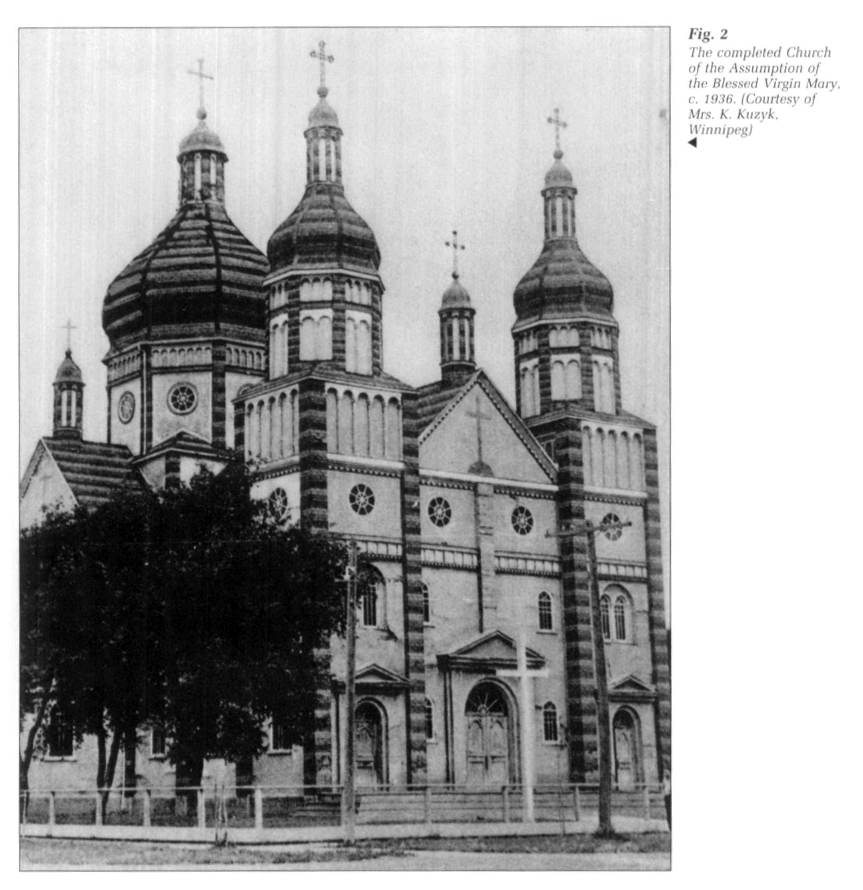

13 Although the grand dimensions of the edifice were already apparent in 1927, and had then so impressed Mayor Burns, the completed church was even more striking. At its largest exterior dimensions, the edifice was 170 feet long and 100 feet wide (52 m by 31 m) and attained a height of 104 feet (32m).29 For its general architectural form, Ruh had relied on a cruciform plan, from which the walls climbed "uninhibitedly upwards ... to blend with the skyward reach of cupola and cross."30 The wooden walls were covered with rough cast stucco,31 which gave the church a pristine, glowing appearance. The roof was shingled. There was one main dome or cupola, two frontal towers, each with its own cupola, and four subsidiary, more stylized, cupolas. At the base of each cupola, large and small, were blind arcades. The many windows punctuated the exterior appearance with their striking shape and muted colour. The cupolas were covered in steel and topped by steel filigree Byzantine-style crosses. As was common in the Ukrainian tradition, a freestanding bell tower completed the external configuration. Until the time of its demolition, the church's "green and silver domed spires dominate[d] the town's horizon."32 In the words of another writer, "The structure does tower over the cultural enclave of the Portage la Prairie Ukrainian community."33

Display large image of Figure 2

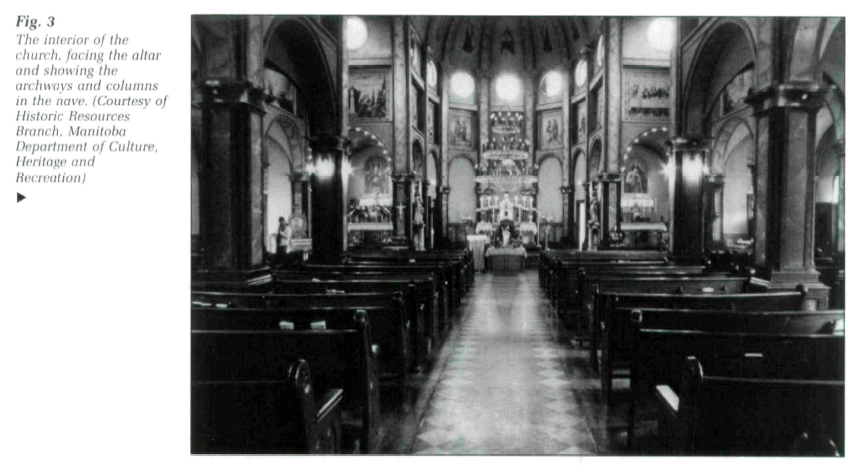

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 314 As with all his larger churches, "Ruh combined precepts and elements from Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic, Ukrainian Baroque, and vernacular" architecture.34 Even though there was no iconostasis, and there were some religious statues and other Western influences, the interior of the church marked it clearly as a Ukrainian church. Its striking visual impact was due to the scope and skill of Ruh's design, the ingenuity and craftsmanship of the carpenters in their use of interior materials and the general impression created by Kvrylo Sych's work, even though in its detail it was far from flawless.35

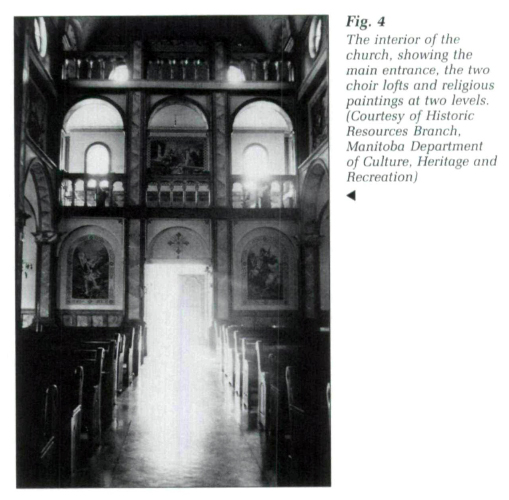

15 Upon entering the church, one stepped into the babynetz, the porch, which was largely unadorned, with doors leading into the nave and steps going up to the two choir lofts, one above the other. Central double doors led into the main body of the church. The first impression given by the tall, barrel-vaulted interior was one of grandeur, balance and harmony, an effect created by the combination of light, colour, height, space and ornamentation. Although the fullness of the crowning feature of the church—the central dome over the crossing of nave and transepts—was not immediately visible, the viewers' attention was immediately drawn to this intersection, and beyond it, 110 feet (34 m) away, to the altar, and also to features above eye level. Both side wings of the nave were trained in arches reaching to the ceiling. On the walls were a profusion of religious paintings,36 placed at three levels and encircling the church in an orderly, harmonious pattern. At floor level there were also one-storey-high arcades or aisles along the east and west walls, which opened through colonnaded archways into the nave.37 Columns supporting the upper walls extended above the arches to the vaulted ceiling and were also used at the crossing and in the sanctuary.38

16 The focal point of the interior was the main dome. It opened majestically out of the meeting of the arms of the cross. Here, the impression of spaciousness, of reaching heavenward,39 was strongest. The dome was adorned with a row of religious paintings above a blind arcade. From the dome's centre hung a chandelier.40 The semi-circular sanctuary, where the altar stood, was a fitting complement to the architecture of the nave, transepts and dome. The ceiling of the sanctuary curved inward toward the dome, its semi-circular shape accented by the six curved columns or ribs, like those of a great umbrella, enveloping the entire area of the altar.

17 The architectural effect of space was magnified by the interior decoration: a guidebook to Portage could validly describe "the richly coloured interior" as "the highlight of the church."41 The columns and arches throughout the church were painted to resemble marble. Whether done by Sych or one of his helpers, the trompe l'œil was remarkably successful, and lent the church the pomp of real marble.42 The profusion of religious art on the walls further enhanced the splendour of the interior, so that it could without exaggeration be called "a celebration of the mural artist's craft."43 An appropriate setting for the more than fifty murals was created by Ruh's design, including the placement of the windows as sources of light. There were large windows on the first floor level, and round Windows above every arch in the nave, in the transepts and in the sanctuary, and in each wall of the hexagonal main dome.

18 In content, the fifty-six paintings were typical of Eastern Christian icons, although the style of painting was decidedly influenced by Western religious art and by Sych's own untutored skill and craft. The paintings were on canvas glued to the walls. Stencilled borders of geometric, Ukrainian-style motifs hid the irregular cut of the canvas. Even though most of the paintings were not icons in the strict sense, their large number, placement and general iconography were a clear transference of the Byzantine tradition of the parishioners. The paintings reiterated, according to one art historian, "the symbolic meaning of transcendence."44

End without Honour

19 The church had been lovingly built and elaborately decorated. But the materials used for the roofing and exterior finish were of poor quality. Over the years the roof leaked, causing water to collect in the walls. The walls were not properly insulated and prepared for the stucco; they became damp and loose pieces of stucco came away or crumbled as early as the 1930s.45 Minutes of parish meetings in the late 1930s and throughout the forties and fifties show that the need for repairs to the exterior was frequently under discussion. However, a meeting in 1938 specifically to discuss repairs to the church attracted few members, "because they aren't interested in church matters." That same meeting considered what type of siding should be used to cover the walls, and some pledges of money were received,46 but it was not until 1942 that the decisions were made to use Insulbrick and to hire a contractor at fifty cents an hour.47 The external appearance of the church was greatly changed as a consequence. Roofing repairs were approved in 1942 and discussed again in 1949, but it was apparently not until 1965 that a complete re-roofing was done.48 Minutes in early 1950 noted there was rot under the church, the ventilation needed improvement and some joists needed fixing.49

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 420 Severe deterioration took place in many parts of the structure, assisted by procrastination in carrying out repairs. And what was done with the best of intentions occasionally had detrimental effects. The Insulbrick applied to the exterior walls exacerbated the deterioration of the walls because its waterproof tar composition trapped the condensed moisture from the warm air inside the church.50 Only the murals inside the church were spared the damage caused by condensation, roof leaks and marked temperature changes.

21 The condition of the church caused increasing concern among the congregation. An architect, N.M. Zunic, estimated in 1971 that the cost of restoration might range between $49,000 and $130,000.51 The following year a contractor gave an estimate. In 1974 the provincial Department of Cultural Affairs and Historical Resources was asked by the parish to examine die building. The department's restoration architect and interior designer noted main defects, some of them serious. They were careful to suggest that only a thorough study by structural engineers could provide definitive answers to many questions. They thought the building could be completely restored if the congregation so chose, though this would be more costly than the erection of a new building.52

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 522 No such thorough structural examination appears to have been made. Instead, the congregation opted for a new church, which was built in 1981-82. The parish meanwhile considered what to do with the old building. Subsequently, they claimed they really bad no choice: permission to build the new church had been given on condition that there be ample off-street parking, which could only be provided if the old church was demolished and the site turned into a parking lot. In the fall of 1982 the parish decided to tear down the old church. The Manitoba Historical Sites Advisory Board then initiated a review to determine whether the church should be designated a historic site. Such designation would have enabled the Manitoba government to intervene. To enable the review to be completed, the Portage city council extended its deadline for clearing the site to 1 June 1983.53

23 The parish, perhaps alarmed by increasing publicity, pressed on with its own agenda. During February 1983 the parish priest, Rev. J. Radkewycz, authorized and assisted the parishioners to remove thirty or more murals from the walls,54 which was done in a crude and unprofessional manner. This action effectively thwarted any possibility that the church might have been designated a historic site: as the chairman of the Historic Sites Advisory Board noted, the artifacts that had been removed had constituted one of the main reasons for the building's preservation.55 Despite mounting media attention in Portage and elsewhere,56 there was not sufficient local will to save the church. At 8:00 A.M. on 2 March 1983, the old church fell to the wrecker.

A Goodly Heritage

24 For over fifty years the Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary was the place of worship and the core of cultural and social life of Ukrainian Catholics in Portage la Prairie. During the depression years the congregation did what they could to maintain and even improve it. But they had insufficient knowledge of the building's structural details, how to maintain such a large wooden edifice and how best to repair any faults therein.57 The historian might say the thrift-conscious parishioners adopted a Band-Aid approach to the maintenance of their church. This is not surprising, especially given the reluctance of the parishioners until the early 1970s to look for advice outside their own ranks.58 It was not insensitivity to the historical worth of the church but lack of knowledge of what to do about its structural problems that brought it to its sad state of disrepair by around 1970. Considerations of safety then spurred the parish council to investigate more aggressively the extent of the deterioration. Restoration remained an option, but at high cost, and no structural engineer ever examined the building. Nonetheless, the decision was taken to build a new church.

25 One must presume the decision was not easily made. The church was in poor condition. Its full restoration represented a cost of unknown dimensions, against the known cost of building a new structure. Moreover, the old church, despite its beauty and its meaning in the lives of those who had taken a role in its construction (and perhaps of their immediate families), was relatively expensive to maintain. Given its mass, it could not be adequately heated in winter; indeed since the mid-1960s, the parish hall and not the church had been used for winter services. Pragmatic considerations argued for the construction of a new church.

26 Even some of those who had assisted in the construction of the old church were resigned to its demolition. "A time comes and things pass" was the sad comment of one. In any case, there were fewer and fewer of these parishioners, for many had died and others had moved away. Perhaps the old church was not as meaningful to the children and grandchildren, who had received it, so to speak, as a gift, as it had been to the generation that had struggled and sacrificed to build it. Perhaps it had still less meaning for those who had moved into the parish after the Second World War. Possibly some of the younger and upwardly mobile people of the 1970s were some-what ashamed of the cheap materials, which had been so marvellously fashioned and shaped by the craftsmen.

27 Such reasoning is obviously speculative. What is plain, however, is that while the new church was being planned and then built, no clear decision had been made about what to do with the old building.59 Perhaps some members of the congregation thought the construction of the new church ipso facto meant the old one would be torn down. A small number of parishioners did want to save it, or at least to find out "whether or not restoration would be possible for a summer-type church-museum."60 As the author of a circular letter to parishioners put it so poignantly, "We inherited this building from the generation preceding us, so it is not really ours to do away with indiscriminately. We have an obligation to pass it on to the next generation, if at all possible. It is our most visible link with those immigrants who toiled with their own hands to build this magnificent building."61

28 Unfortunately, all too few parishioners shared this viewpoint. Possibly it was again their pragmatism that triumphed. Restoration and continuing maintenance involved money. Why preserve something for which a modern and more comfortable replacement had been built? If the old church remained, how could the parish meet the city's requirement to provide off-street parking? It owned no other land and had no funds to buy any.62

29 In all of this one may discern an insufficient appreciation of the old, of the historically valuable, of the visible symbols of heritage—an attitude regrettably not uncommon in many parts of North America. It is certainly not an attitude only of the Ukrainian parishioners of Portage la Prairie. Indeed, one of the disconcerting aspects in the circumstances surrounding the demolition of the old church was the apparent indifference of the non-Ukrainian population to the imminent disappearance of a city landmark. The church, after all, was a historic site for all "Portagers," not for just the church members. "But some people have a sense of history and some don't."63

30 The latter seem to predominate, at least unless one level of government or another steps in to pay the bills. Parish officials claimed in 1982-83 that they had earlier requested assistance from the federal and provincial governments and had received no satisfactory response.64 The province of Manitoba has no great record in protecting "the physical reminders of our past."65 The federal government has taken a greater interest, though much of it was directed to preserving "a lot of anachronistic old forts."66 It is notable that of the seventy-two national historic parks and major sites listed in 1985, three commemorate Indian or Métis people and all the others are memorials to the British or French "founding nations."67 The British and French are an important part, but not the only part, of Canada's historic heritage. One hopes the contributions and heritage buildings of Canada's other component peoples will also get federal government recognition and support.

31 Such assistance cannot come too soon. In Manitoba, the Ukrainian Catholic church in Brandon appears to be under threat; its current priest is the same man who was the priest in Portage la Prairie in the early eighties. And the Church of the Resurrection in Dauphin, the best remaining example of Father Ruh's larger churches in Manitoba and a local landmark for fifty years,68 is under imminent threat from a congregation that wants a larger church. Will these historic churches go the same way as the Portage church, where, to quote Joni Mitchell, "they paved paradise and put up a parking lot"?