Articles

Three Urban Parishes:

A Study of Sacred Space

Different but related streams of parish life are reflected in the material culture surrounding three Ukrainian Catholic congregations in Edmonton, Alberta. Variations in architecture, interior space and iconography show the impact of history and shifts in cultural symbolism, human imagination and tradition.

Résumé

La culture matérielle propre à trois congrégations catholiques ukrainiennes d'Edmonton, en Alberta, reflète des courants de vie paroissiale distincts mais apparentés. L'architecture, l'aménagement intérieur et l'iconographie ont subi des variantes qui soulignent l'importance de l'histoire et de l'évolution du symbolisme culturel, de l'imagination humaine et des traditions.

1 When we consider the material culture of the Ukrainian community in Canada from its initial settlement to the present, there is one large source of objects that immediately comes to mind: the Church. To the larger Canadian society, it is a hallmark of the Ukrainian tradition; to many Ukrainians, it is the centre of social, cultural and religious life. The church, whether Eastern Rite Catholic or Orthodox, was virtually the first institution to be built in communities across the Prairies early in the century, was maintained throughout the life of the founders down to the present day and continues to serve hundreds of rural and urban communities from Halifax to Victoria. In it we find the symbolic core of Ukrainian tradition. Tradition is embodied in the architecture, the iconography and the liturgical drama, played from evening to evening throughout the weekly cycle of services and the liturgical seasons. From the church, the faithful are taken and laid to rest in the cemetery. To the church, the newborn are brought and baptized into the Kingdom of God. The religious and much of the social and cultural life of the community occurs here; and, here, surrounded by the gathered saints (typified in the icons) and in the presence of the drama of the liturgy, the meaning of life in all its fullness is sanctified and celebrated.

2 This process of sanctification and the role of Ukrainian church architecture and iconography are the focus of this paper. The Eastern Christian community has the richest symbolic tradition in Christianity. Its ritual system provides and shapes this process of sanctification. Its actions are understood as the primary work (leitourgia, "public work") of the faithful and are best carried out with the full weight of tradition helping to form and inform the meaning of the action. How has the tradition of architecture and iconography fared in the process of being transplanted to Canada and the modern world?

3 Through an examination of three Ukrainian Catholic parishes in Edmonton, Alberta, we can glimpse how the vagaries of history have affected the shape of the religious material culture of the Ukrainian Catholic community in Canada. We will examine the architectural setting and iconography of these three parishes and reflect critically on their relationship to the symbolic tradition in which they claim to be rooted.

Three Parishes, One Tradition?

4 St. Josaphat's Cathedral in Edmonton, the seat of the Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy, gave birth to St. Basil the Great Church in 1967 and to St. George's Ukrainian Catholic Church in 1955. All three serve the Ukrainian community. All three use the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. All three are under the same bishop, though St. Basil the Great is served directly by a religious order, the Basilian Fathers.1 These three churches are distinct in their architecture and icongraphy, in the shape of liturgical services and in the languages used to serve the liturgy. Together, they tell us a great deal about how the liturgical tradition has been embodied in the current historical situation. This paper focuses on architecture and iconography, leaving the shape of liturgy and liturgical language to other studies.

5 The Church of St. Josaphat was built in 1904.2 The present structure was built in 1939. Pope Pius XII divided the one Eparchy that served Canada into three on 3 March 1948. The Eparchy of Edmonton was formed, and St. Josaphat's became a cathedral, the bishop's see. At the time, it was under the administration of the Basilian Fathers and was the sole Ukrainian Catholic parish in Edmonton. The Basilian Fathers have been the primary clergy to serve the Ukrainian Catholic community from 1902.

6 St. Basil the Great Church had a humble beginning on 2 November 1947, when Father S. Kurylo, OSBM, began regular services in St. Anthony's Separate School.3 The parish was formally established by Bishop Neil Savaryn, OSBM, in 1948 to serve the needs of Ukrainians residing in the south side of Edmonton. It moved from worshipping in a Roman Catholic church to St. Basil's Cultural Centre, the first building completed on the site, to the completed church on 24 September 1967. The Basilian Fathers included a large residence and monastery along with the cultural centre and church on a singularly impressive site.

7 St. George's Ukrainian Catholic Church was formed in October 1955 and moved into its current classical Byzantine-style church in 1981.4 The crisis leading to its formation was a series of changes in the liturgical pattern at St. Josaphat's, culminating in the adoption of the Gregorian calendar as the indicator of the feast day cycle.5 Although the bishop requested that services by the liturgical calendar (Julian, or old style) continue to be offered for those who wanted them, this compromise was found unsatisfactory. After several years a portion of the community sought to establish a new church, faithful to the traditional feast-day cycle. The request was granted by Bishop Savaryn, and the parish of St. George's was formed. This parish has been influenced by a Byzantine liturgical renaissance, a movement found in numerous Orthodox and Eastern Rite Catholic churches in this century.6

Design and Building

8 St. Josaphat's Cathedral was designed by Father Philip Ruh, OMI. Construction began in 1939 and was completed with the solemn dedication in 1947 by Cardinal Eugene Tisserant, Secretary of the Congregation for Eastern Churches. Father Ruh was born in 1883 in Bikenholtz, Lorraine, Germany, near the French border. At fifteen years of age, he was sponsored by the Oblate Fathers and studied in their novitiate in Holland and later in Germany, where his interest in art and architecture blossomed.

9 After his ordination, Ruh was sent by his superiors to work with the Ukrainians in Lviv. He stayed initially with Metropolitan Andrew Sheptytsky, a father of the Byzantine liturgical renaissance in the Ukrainian church, and later at the Basilian monastery in Buchach, where he learned Ukrainian. On 20 April 1911, he left Europe for missionary work among the Ukrainian immigrants in western Canada. During his tenure in the West, Ruh built many churches for the Ukrainian Catholics, from Grimsby and St. Catharines in Ontario and the "prairie basilica" in Cooks Creek, Manitoba, to St. Josaphat's in Edmonton. He was also the architect for Our Lady of Lourdes grotto at Skaro, Alberta.7

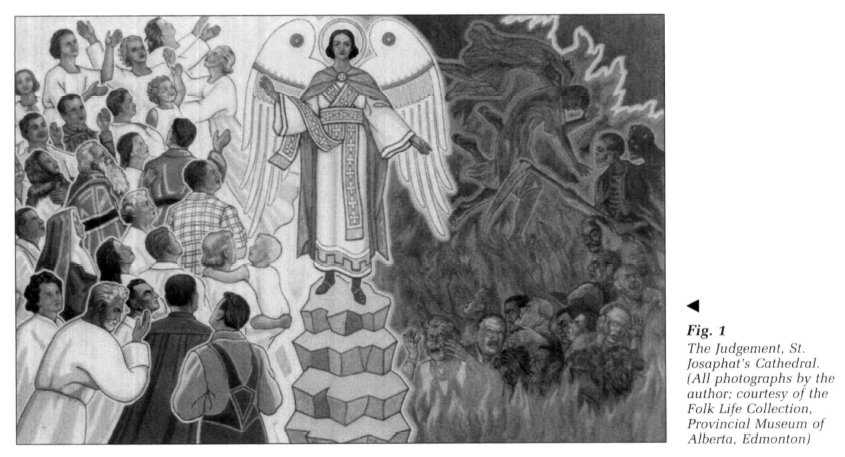

10 Father Ruh used a rather eclectic mix of architectural styles in designing St. Josaphat's Cathedral. Although it greets the eye primarily as a Byzantine-style church, one does hesitate over several features. The cornices on the drum that support the cupolas and part of the facade are based on Roman style, while the cross-supporting smaller cupolas and drums, set on an arch of the large cupolas, are in the Renaissance tradition. The columns in front of the facade are in a pseudo-classical or American colonial style. The cathedral has seven octagonal copper cupolas, each topped with a Roman cross. Only the central cupola is open on the inside, playing a role in the interior iconographic design of the church. The walls are red brick with pilasters of darker brick and ornamental crosses of yellow brick in the upper sections. It is a two-storey building with the upper portion serving as the church proper: sanctuary, nave, transept, four added square areas in each corner where the transept meets the nave (two of which are sacristies) and narthex. A spacious choir gallery extends over part of the nave and the narthex. The chancel is raised three steps above the floor with the first step serving as a solea. The iconostasis was designed by Professor J. Buchmaniuk.8

11 The interior space of Eastern Catholic churches is by tradition covered with iconography.9 Virtually all the visible space, from the narthex through the nave, side aisles and transepts, and sanctuary to the apse and domes, is painted according to a form developed in the Eastern Christian tradition. To enter such a church is to enter the gathered community of the redeemed. The whole church is an icon of the presence of the Kingdom of God moving from the prophets of the Hebrew Bible toward the Christ, and from Christ outward in the lives of the saints and the gathered people. They are all present, all one in the gathered kingdom of which the church is a microcosm.

12 Eastern Christian churches are temples, not meeting houses.10 As with the whole tradition of temple cult in world religions, we have here a microcosm, a sacred space. The specific meaning of these churches is an archetype of the "restored" creation, a world of communion free of alienation, the "image and likeness" of the creation as God intended it. For this reason, there are canons governing the design of these churches, and portions of them are built ritually.

13 Professor Julian Buchmaniuk was commissioned to do the iconography for St. Josaphat's Cathedral. He was born in Smorziw, Galicia, western Ukraine, in 1885. In 1908 he entered the Academy of Art in Krakow and, as a student, visited art schools in Munich, Rome, Florence and Milan. He painted the Basilian monastery chapel in Zhovkva. Later he studied at the Czech Academy of Art and was an instructor in several schools in Lviv after the First World War. He came to Edmonton in 1950 and began the monumental task of painting St. Josaphat's. Along with designing the iconostasis and doing the wall mural painting, he painted the icon of the Theotokos (the birth giver of God) and icons of Christ and St. Josaphat. The icon of St. Nicholas and the icons on the royal and deacon's doors were painted by Parasia Ivanec, and the festal icons on the iconostasis were painted by Ivan Denysenko.11

14 The painting of Buchmaniuk uses elements common to the neo-Byzantine style. However, this is as close as the painter comes to a regard for the iconographic tradition of the Eastern Church. Parishioners suggest that this church is in the "baroque style, with realistic traits, which had become, as it were, the Ukrainian style, accepted under the influence of Netherlands' baroque, with some Byzantine elements." We are told that the

15 Apparently Buchmaniuk used models for many of the figures. Various members of the congregation are recognizable in the paintings.13 He also included in the murals a painting of God the Father on the central cupola, completely foreign (one could even say heretical) to the Byzantine tradition. His attempt to depict the "divine attributes of majesty, omnipotence and infinity" resulted in a rather fierce image. The artist was asked to tone down the painting so that it would not inspire quite so much dread in the viewer.14

16 The immediate impression on entering St. Josaphat's is that one is entering another world. It is completely painted in soft pastels, delicate and pleasing. The column and arch structure is womb-like, yet expansive. The central dome opens as the canopy of heaven; one is caught up in regard.

17 All of Buchmaniuk's painting is stylized. Elements of neo-Byzantine style can be discerned. What is remarkable is that the neo-Byzantine tradition is not in any way the artistic much less iconographic tradition influencing the overall work. The ornamentation—doves with marvellous swoops of air, fish with bubbles of water, lovely floral motifs and grape tendrils—is simple, with a fine sense of graphic design. It gives the impression of a Victorian picture book prepared for a child's imagination (as adults oddly abstract it), exuding innocence, charm and delight.

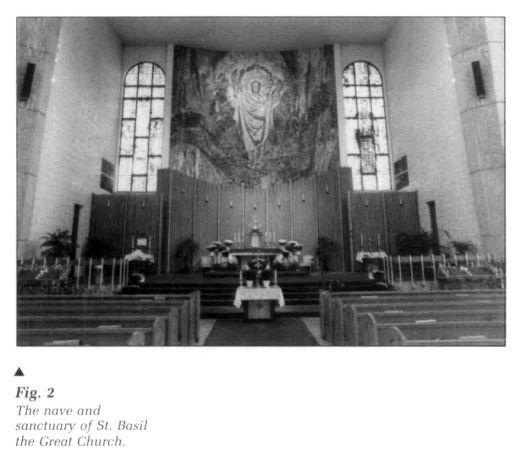

18 The human figures contrast oddly with the decorative work. While the torsos of the biblical figures are line drawings, flat and outlined like the animals and flowers, the heads are fully developed naturalistic portraits painted in deeper colours, images of the folks next door. They differ only in having a propensity for beards and the wearing of rather odd clothing. This type of portraiture can be found in Protestant Sunday School literature from the late nineteenth century through the 1950s, and this is clearly the tradition governing the general work. Realistic, perfectly natural and quite cozy. Cozy, that is, except for the image of the Last Judgement. To the right of the angel (a fire marshal in action), "bathed in the light," is a "family portrait" of the redeemed rejoicing (fig. 1). To the angel's left, along with Stalin, Hitler, a local art critic and Marxist, are the damned reaping their denial reward midst the monster death. Flames abound; torment reigns.

19 The angels throughout are like the ornamentation—stylized, free of individuality, decorative. On the walls of the nave are full-length portraits of various clergy who figured in the history of the parish. These look like photographs from a newspaper or parish bulletin, carefully coloured.

20 St. Basil the Great Church was designed by Eugene Olekshy, an architect and member of the parish. He worked closely with the various parish committees and the Basilian Fathers who serve the parish. A rather lengthy process was required to amass the necessary land for this large project. In April 1964, the plans for the building complex (church, cultural centre and monastery) were completed and sent for approval to the Basilian hierarchy including the Superior General in Rome. In December this was granted. Construction was complete in the summer of 1967.15

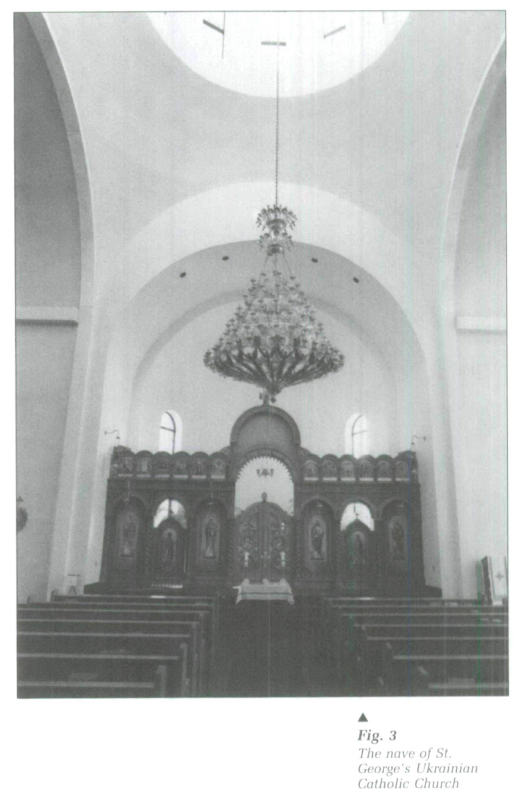

21 Olekshy's design has the church sitting on a very large plaza flanked on the south by the monastery. It is a large building, some 14,000 square feet (1,300 m2) on the main floor with a seating capacity of 1,200. The main body of the church has a clear height of 45 feet (14 m) with the domed section in the centre rising to 90 feet (27 m). No columns exist to hold up the dome as in traditional building forms. The dome has a diameter of 50 feet (15 m). The building is a square structure with a colonnade ringing it. The central dome, colonnade and soft arch decorative features are the only hint of the Eastern sensibility at St. Basil the Great. Despite this, the educated observer familiar with the architecture of the Christian East would not readily identify this structure as a church of the Christian East. However, the parish identified it as Eastern and Ukrainian, suggesting it retains "the basic characteristics of the Byzantine rite of the Ukrainian Catholic Faith."16

22 The building material is precast concrete, sandblasted to give "a pleasing texture." The exterior walls art; constructed of tweed tan brick on lightweight concrete block infill. The interior finished wall surface is a coloured, split-face, lightweight concrete block laid in a scotch bond pattern. Minimal maintenance cost seems to have determined the finish.

23 The casual observer cannot help noticing that all the materials used in the exterior construction are man-made; nothing is God-given. No wood or rock speaks of nature, a gift of creation. Rather, it is all a poured soup, formed by nothing intrinsic, having no inner fidelity, made solely for the convenience of a rude building process.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 124 The building materials used throughout the interior of the church are all commonly found on the exterior of modern office and civic buildings. One gets a little relief from this with the wooden decorative features that form a backdrop for the altar table and frame the side chapels and confessionals. They are warm, but curiously free in design of any specific meaning, an irony when we consider the meaning virtually everything has in an Eastern Christian church built according to the tradition. The marble finish to the walls and floor in the sanctuary stand in contradiction to the concrete "exterior" character of the nave; the viewer feels as if standing outside, looking into the interior space. The total space has the feeling of a thoroughly public area, free of any but the most functional meaning (fig. 2).

25 A dome hangs suspended over the centre of the nave with no echo in the architectural features of the interior or exterior. From the outside it looks like a poorly fitted hat, a beanie far too small for what it is to cover. It clearly is not the "canopy of heaven" much less a symbolic marker of the cosmos transfigured by the light of Christ. According to tradition, the dome is normally accented by an icon of the Pantocrator in the dome, but it is not to be found here either. The dome is not integral to the structure, but simply added to identify this as a Ukrainian church. The effect is to give one a sense that the heavens may plummet at any time; one cannot help but wonder if it promotes a form of "chicken little" spirituality. While the fathers and mothers of the Eastern Church were fond of saying that the church is a type of "heaven descended," this plummeting heaven is clearly not what they meant. Creation is transfigured in the divine liturgy and seen to dwell in the eternal. The symbology should not suggest alternate realities desperately trying to reach each other.

26 St. Basil's has no iconostasis. It simply was not constructed to have one. The use of iconography is minimal. A large mosaic of Christ shimmers metallic above the altar table. Christ is shown triumphant with hands raised in blessing against the backdrop of the cross, flames illuminate the area around him and the landscape is in chaos. It is apocalyptic, harking to the destruction of our fragile earth.

27 The only icons in St. Basil's are on processional banners. Stained-glass windows (a Roman Catholic feature) of the life of the holy Virgin and, in the entrance, of the life of St. Basil the Great resemble the iconographic tradition of the Christian East.

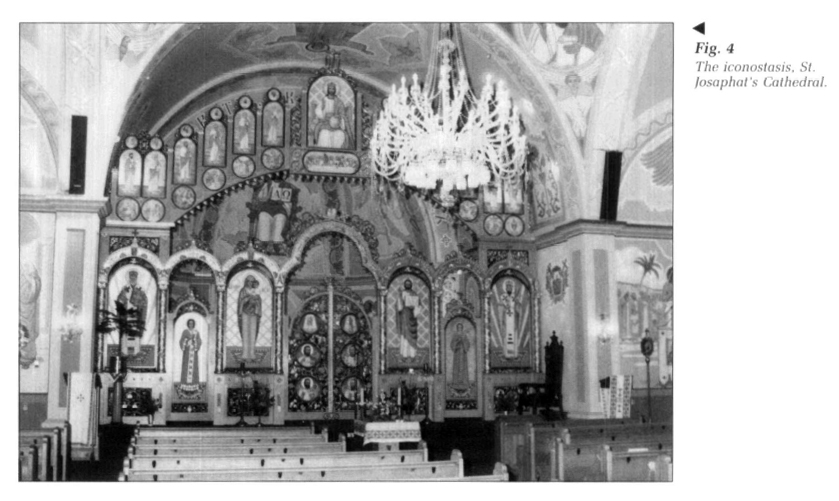

28 St. George's Ukrainian Catholic Church was designed by Andrew Baziuk, a local architect, under the direction of the artistic committee of the parish.17 St. George's has a number of professionals and academics as members and made good use of them on this committee. The result shows in this pristine, well-appointed structure. It is modeled on the thirteenth-century Church of St. Basil in Obruch, Volhynia, Ukraine, a church in the classical Byzantine Style. A clear concern for a church which would serve the liturgical action of the faithful was stated at the beginning of the planning process: The architecture must not impose any limitations on the actions of worship. There was unanimity in the committee about the role liturgical tradition was to play in their decisions. This can be briefly illustrated by the discussion when the architect suggested that confessionals be built to the left of the sacristy. Although many at St. George's were familiar with the use of confessionals from their time at St. Josaphat's, confessionals are a Latin accretion and not properly part of an Eastern Church. The confessionals were ruled out unanimously. The architect also suggested that several thousand dollars could be saved by building the transept roof in an angular fashion on the outside where it would not be seen and accommodating the curved style called for by tradition on the inside. Again, the committee opted for the additional expense on the grounds that "it was right" for the structure to be coherent inside and out and that tradition should be followed faithfully. This pristine church was opened in 1983 (fig. 3).

29 As tradition dictates, the interior was built with an iconostasis in mind. The parish's attention turned to this feature as soon as the building was completed. In 1983 they installed an iconostasis made in Greece by Argyrios Kavroulakis. Currently, parishioners are trying to choose the iconographer who will receive the commission for the murals, festal iconography and the icons on the iconostasis. Three iconographers are being considered — Hieromonk Juvenali, Heiko Scheiper and Michael Moroz. Debate on the issue reflects the sensibilities and interests of the parish.

30 Hieromonk Juvenali of the Studite Monastery, Woodstock, Ontario, paints in the style of the neo-Byzantine revival. He has an excellent reputation in the Ukrainian Catholic community, having painted the Patriarchal Cathedral of St. Sophia in Rome. St. Sophia is the church built by the late Iosyf Cardinal Slipj and is the central church for the Ukrainian Catholic community throughout the world. He is favoured because of his style, reputation and Ukrainian identity. Unfortunately, Juvenali will not be able to paint the necessary murals and icons for some years.

31 A second iconographer, Heiko Scheiper, has painted the interior of Holy Protection Church in Toronto in a modified form of the Novgorodian style. His superb work has received considerable attention from the parish. However, Scheiper is not Ukrainian; although he has offered to work in styles representative of Kievan Rus', some parishioners would prefer an iconographer of Ukrainian ancestry.

32 Recently, a member of the committee viewed the work of Michael Moroz, an iconographer living in Germany. He studied at the Monastery of the Caves, Kiev, and works in the classical Byzantine style with a touch of the late-Muscovite-school influence.

33 One member of the committee did argue for the consideration of a Ukrainian iconographer working in the naturalistic style. His work, however, was deemed inferior, and the naturalistic style considered an affront to the classical form of the church and incompatible with the theology and spirituality of the icon.

34 St. George's is a lovely classical Byzantine church, despite several obvious architectural contradictions on the exterior. The plate windows and the use of small, standard-size bricks contradict the fortress-like structure. They do not carry the weight and solidity of the architectural style. Similarly, the use of a concrete, wave-like feature to cape the roof and join it to the walls has a modernistic flavour not particularly suitable to the classical form.

The Divine Presence: Sacred Space

35 The style of church architecture that developed in Eastern Christian tradition is understood as a form of revelation. Its fundamental insight is that God is present in all creation. This idea is distinct from Western Christian tradition, which tends to see the fall of Adam and Eve as ushering in a rupture in nature that changed the ontological character of the cosmos. The East argues that the fall was essentially a problem in how human beings understand the world, an epistemological tragedy healed by Christ's entry into death. Through the liturgy, humans participate with the Creator in restoring the sanctification of the cosmos.

36 The characteristic dome of Eastern Christian churches suggests a transfigured world. The temple, "heaven descended," is the prototype of a "sanctified creation." There is no pointing beyond creation like the spires of Western churches. Rather, the church is a dwelling place of all that is real. The church is the presence of the Kingdom of God. In it all things are united, all creation is revealed in its fullness.

37 The Eastern Christian church has a vestibule where people enter, a nave where the assembly gathers as the people of God, and a holy table (altar) area. The altar area is the sanctuary or holy place, and it represents the fullness of the Kingdom of God.

38 According to the Old Testament the people were not allowed to enter the courtyard of the temple, where only certain ranks of priests served. With the coming of Christ, the sacred character of all creation and the priesthood of all believers was revealed. Thus, in the Eastern Church, the laity share in the priesthood of Christ by serving the liturgy in the nave with the priest. The nave—the ship of salvation—is the transfigured "courtyard of the tabernacle."

39 The priest is not above the laity, but has a specific role in the concelebration of the liturgy. It is imperative that the people participate in the movement, the rhythm and the harmony of the liturgical drama. Pews reduce the congregation to observers or, at best, passive participants. "Passivity" is a notion completely foreign to the Eastern Christian understanding of the Kingdom of God. Pews also foster the notion that the priest is doing something for or on behalf of the people of God—again, a foreign notion. All the faithful are priests serving the divine mysteries. All are part of the harmony of the Kingdom of God. All enter into communion and move toward the sanctuary of the cosmos, the ultimate destiny of all creation, symbolized by the holy table in the sanctuary.

40 All three parishes under discussion opted for pews in the nave. The argument for this innovation, which began before immigration, is the need for comfort during the lengthy liturgies. The elderly and infirm have always been provided with pews along the perimeter of even the most traditional churches. Whatever the value of this argument, pews not only invite passivity but, what is more important, render the iconographic pattern of movement characteristic of the various liturgies and rites confused or indiscernible. At St. Basil the Great parish this issue is irrelevant, because there is no iconographic structure either to the church or its decoration.

41 A central feature of the temple as a sacred space is the iconostasis, or icon screen. Functioning as a stand for icons, it contains two sets of doors: the royal doors (or royal gates) at the centre and the deacon's doors at the sides.

42 Even among the faithful, the icon screen is commonly referred to as a divider between the people's portion of the church and that of the clergy. The tradition, however, refers to it as a "bridge of unity" joining the nave (the present Kingdom of God) and the sanctuary (the Kingdom coming into being). It reveals the movement of human life: living in the fragile presence of divine love while remaining open to the fullness of divine love—of complete communion—in the future. In worship this is presented as the archetype of human experience.

43 The iconostasis is integral to the sacred space, for it shows the unity of Christ, the holy Theotokos, the saints and angels, and the faithful. The royal gates bear icons of the four evangelists and of the Annunciation. These gates are between an icon of the Theotokos and child—the incarnation of God in the world— and an icon of the Glorified Christ in the fullness of the Second Coming. These two icons reveal the central eschatological mystery at the heart of the liturgy, at the heart of life. They are often referred to as the icons of the First and Second Coming of Christ. Liturgy and life, the tradition teaches, are in the midst of these two cardinal realities. In the life of the faithful, baptism is the incarnation of Christ; their longing for the fullness and perfection of life (the Kingdom of God) is typified by the icon of the Glorified Christ.

44 St. Josaphat's (fig. 4) and St. George's (fig. 3) parishes both have iconostases that function according to the tradition. The movement of the liturgy uses the royal doors and the icons of the Theotokos and of Christ Glorified to call the faithful to a deeper apprehension of the presence of the divine. In both cases, however, the processional movements are constricted by the pews in the nave from showing a theophany, or the movement between these two realities. Instead of celebrating and calling all creation to the fullness of the sanctified life, showing the faithful how deeply their experience is informed by this movement, the processions arc reduced to a parade of the clergy. St. Basil's, having no iconostasis, is entirely without the possibility of this part of the action of the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom.

Image and Likeness: The Icon

45 The principal form of liturgical art in the East is the icon. Icons speak in form, content and style of the transformation that takes place in human experience when it is touched by God's grace. Hence, icons are not depictions of scenes in sacred history or reminders of biblical revelation. They are living presence, "a vector of divine grace," as the church fathers were fond of saying. Icon painting is not concerned with depicting what is commonly seen in the world, but in changing the common vision, renewing it so that the share of all creation in the eternal is glimpsed.

46 Icons often strike the Western eye as primitive and naive. They challenge our way of seeing the world, our personal and fashionable "images" of sacred scenes and personages. This is intentional, part and parcel of the canons governing the preparation of icons. In Western easel painting well into this century it was customary to paint as the eye sees—light and perspective affecting size, shape, colour and degree of visibility. Sacred statuary common to Roman Catholic, churches in recent history similarly depicts the human condition, filled with joy or sorrow—or, if the artist would have it, in merely a sentimental manner.

47 In the iconographic tradition, on the other hand, the viewer is a participant. The lines of perspective in the icon come to a point behind the viewer, suggesting that the viewer is part of what is depicted. Indeed, that is precisely the teaching of the church. All human beings participate in the realities depicted in the icon. All creation is invited to the moment of transfiguration shown in the icon.

48 There is no single source of light in icons. Light appears to illuminate from within. No shadow is cast. Just so, the divine light illumines all creation, calling its full reality into being, without shadow or darkness. Similarly, there are no roofs in the buildings shown in icons; this points to the unity between the heavenly kingdom and the transfigured content of the icon.

49 The transfigured life is not bound by time. By definition, it is free of the decay that characterizes historical existence. Christ and the saints live in the eternal presence. Thus, the image of the saint in an icon is not a portrait. Rather, it depicts the spiritual and physical reality, occurring in time, in history, in the individual. The person is essential. No symbol is allowed because the person is "the image and likeness of God." Yet, saints are not painted in the midst of the distorting vagaries of life, in the grip of a transient condition. The eternal incarnate in their person is, in the end, their reality. That is what the icon claims.

50 The figures in classical Byzantine icons are shown in a stylized manner, not lifeless, but deathless, having been transfigured by divine love and freed of the vagaries of history. The soul is not redeemed without or outside the body. The total person has the fullness of life. Theosis, the process of deification, becoming as Christ is, refines the whole being of men, women and children.

51 The only church in this study with a full complement of icons is St. Josaphat's. St. Basil the Great parish has a few icons scattered about on banners, depictions in the Byzantine style in stained-glass windows and the central image of Christ behind the altar of the church. St. George's parish has used the icons from their former building on the new iconostasis, with lithographs of feast-day icons on the upper registers.

52 The highly personal and naturalistic portraiture of the feast-day icons and the saints in St. Josaphat's Cathedral fail entirely to speak of the transfiguration, the presence of the eternal in the person depicted. Consequently, the viewer gains no sense of the transcendent in this environment. Rather, it is as if one has been placed in a storybook world where the illustrator, not wanting the free play of the imagination, has depicted the characters so you almost recognize them from down the block. The sanctity of those depicted is marked by halos, not by the way they are presented, body and soul, as transfigured beings in the "image and likeness" of God. They are completely time-bound, completely given to the vagaries of history.

53 The primary function of the icon cannot operate in this setting. The St. Josaphat icons do not invite the viewer to the reality they portray. They do not call forth the pain and joy in the experience of the viewer, calling it forth to be understood in a new way in the light of divine love. St. Josaphat's has paintings of Bible stories. In no sense are they icons, vectors of the divine love flowing into the life of the faithful during the act of veneration.

54 The depiction of God the Father in the dome of St. Josaphat's is completely beyond anything known in the Eastern Christian iconographic tradition. The canons of iconography stress that the only "image" of God is the incarnation, the Christ. God the Father is never portrayed. And the St. Josaphat's depiction is stylized in a way that has nothing to do with the Creator of life who, the Gospel has repeatedly declared, "is love." The figure appears to be born out of a Jansenist piety, common in nineteenth-century Roman Catholicism (though a heresy), which equates the Creator of life with judgement and damnation. In the Christian East, judgement and damnation are what human beings accept when they refuse life. They are not acts of God's retribution.

55 The stained-glass windows in the cathedral vary from neo-Byzantine style depictions to those drawing heavily on recent holy-painting images in Roman Catholicism. For example, there is a depiction of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in one of the windows, a common Roman Catholic devotional piety early in the century.

56 A mosaic of the triumphant Christ with arms raised in blessing against a backdrop of the cross is the centre piece in the church of St. Basil the Great. Stained-glass windows, in the neo-Byzantine style, of St. Basil and St. Josaphat flank the mosaic. The mosaic bears no resemblance to the iconographic tradition of the Christian East. It is similar in style to much church art produced for North American Roman Catholic churches after the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. This mosaic of Christ makes no attempt to be an icon, but stands squarely in the 1960s style of North American church decoration.

57 There are several Ukrainian Catholic processional banners in St. Basil's. The banners are obviously held in affection by the parish and have been retained for use in liturgical processions. Two of them have icons embroidered in the Byzantine style, quite in keeping with the Eastern Christian tradition.

58 St. Basil's has a number of lovely stained-glass windows in the ambulatory of the nave and in the porch. They are largely within the Byzantine iconographic style and portray a series of feast days, scenes from the life of St. Basil and St. Josaphat and the links with sacred history precious to the Ukrainian people. They are well done and, although stained glass is not a part of Eastern Christian iconographic tradition, they are in style and content the most faithful to the tradition. Of course, they cannot function as icons in this form and serve only a decorative and pedagogical purpose. What is in the mind of an educated clergy which uses the Western form of stained glass to exercise the iconographic tradition of the Christian East? Is it simply a matter of placating the "old" sensibilities, providing the "appearance" of the tradition in a context where it can do no harm precisely because it cannot be used as an integral part of worship? One wonders.

59 The last image that demands attention at St. Basil's is the life-size crucifix between the two main doors through which one passes on exiting the church. It is a contemporary piece with a plaster corpus of Christ on a wooden cross. The crucifix stands squarely in the Roman Catholic tradition of church art, personal, naturalistic, an image of the suffering of Christ. It illustrates the passion and death of Christ and harks to a Roman Catholic piety. In no sense is it an icon.

60 The iconography currently used in St. George's will be replaced when the parish contracts an iconographer to do the interior of the church. The debate over what style of iconography will prevail has yet to be settled, although it seems fair to say that the norms applied will stand well within those outlined by the canons of iconography. An opportunity to develop a sacred space in which the full weight of the iconographic tradition comes to the aid of the faithful—inviting them into the presence of the holy—is on the horizon for the parish.

Conclusion

61 The Edmonton parishes of St. Josaphat's, St. Basil's and St. George's share the patrimony of the Eastern Christian tradition and the Ukrainian people. When the community immigrated to Canada, it came with a memory of how the church was to be built and decorated. It did not come with a properly educated clergy. Rather, the community had to accept the clergy that were available; thus, a range of influences and sensibilities were brought to bear on the development of church structures. Roman Catholic and Protestant aesthetic sensibilities were normal in Canada. They formed a part of the dominant culture. The aesthetic of the Eastern Christian tradition, though held in the collective memory, was no longer part and parcel of the culture in which the people lived, and thus was easily fractured. In many cases, the community adopted images from what was available in Canadian society—Roman Catholic and Protestant "holy paintings." It has taken seventy-five years for enclaves within the Ukrainian community to discover the riches within Byzantine Church architecture and iconographic tradition, to discover the riches of their ancestors. As this movement takes hold (and there are signs across Canada this is happening), the Byzantine tradition in building, iconography and worship will emerge as a call to return to one of the richest symbolic traditions Christianity has ever known.