Reviews / Comptes rendus

Provincial Museum of Alberta, "Seasons of Celebration: Ritual in Eastern Christian Culture"

DESIGNER: Paul Beier.

1 "Seasons of Celebration" is a travelling exhibition produced by the Provincial Museum of Alberta in Edmonton and scheduled to show in at least thirteen centres from Newfoundland to British Columbia over a period of about three years. In addition to recognizing the observance of 1988 as the millennium year of Christianity in the Ukraine, "Seasons" also seeks to provide a comprehensive "glimpse into the marvelous world of Eastern Christian culture" (p.vi in the monograph), including such variants as Greek, Russian, Coptic, and the Mar Thoma tradition from Kerala, India. As such, this exhibit constitutes an ambitious and pioneering effort. Its intent is laudable. However, in its attempt to translate this into practice and, moreover, to focus on the living tradition as found in Canada (a tradition "which stretches back to the time of Christ and continues to inform the life of Eastern Christians throughout the world," according to the free handout) the exhibit tends to overreach itself. After all, how does one use the space limited to a travelling exhibit to show the glories of a striking thousand-year-old heritage that, in this country, took root barely a century ago? Where in Canada are the collections of available "treasures" to draw upon in order to represent this legacy? Where are the mind-blowing artifacts to support headings (in the free handout) like "From Chaos to Cosmos" and "The Sanctification of Creation"? These are only a few of the crucial questions that must have faced David Goa, the Alberta Provincial Museum's Curator of Folk Life, when he initiated research for the exhibit in 1982.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

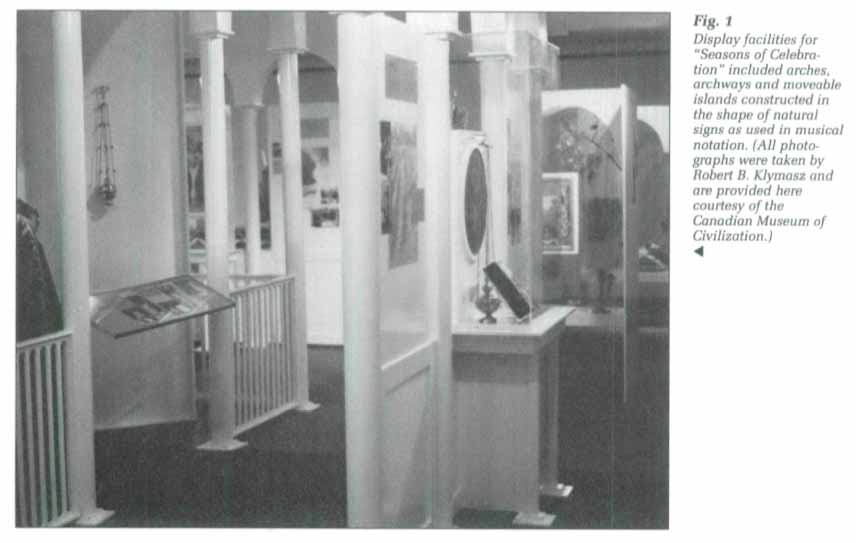

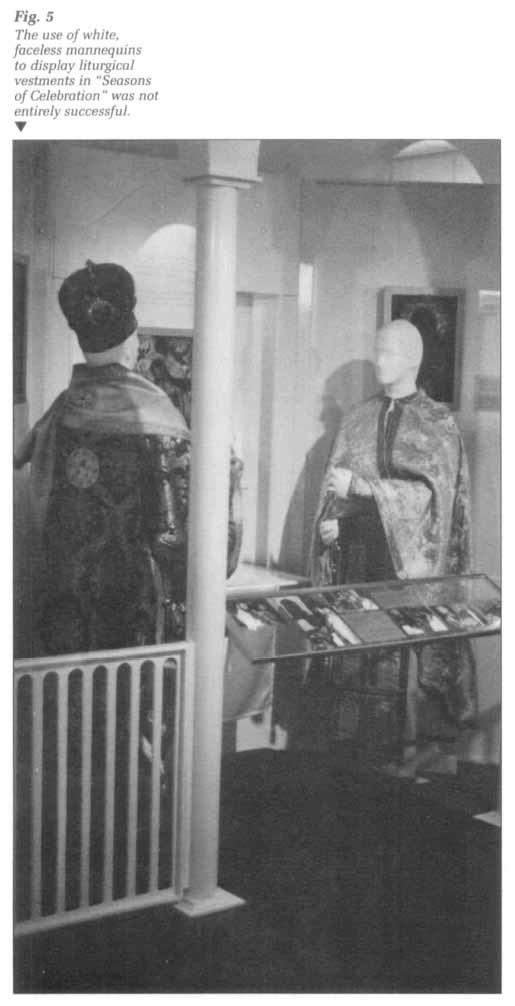

Display large image of Figure 22 In terms of its physical layout, the exhibit is composed of three parts arranged nonsequentially and anchored by a central core-area devoted to "The Word," "The Gifts" and "The Oblation"; this is flanked on four sides by archway-units (focussing, for example, on "Baptism," "Matrimony" and "Holy Orders"). Revolving, so to speak, on the outside of all of the above are four islands of content (constructed in the shape of natural signs in musical notation) covering "Theophony," "Holy Supper," "Transfiguration" and "Slava/Pascha/Pentecost."

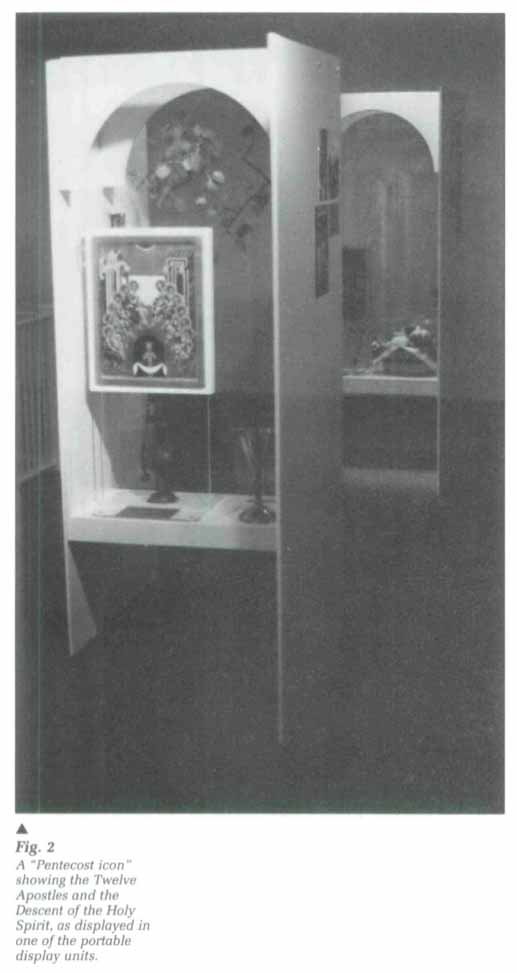

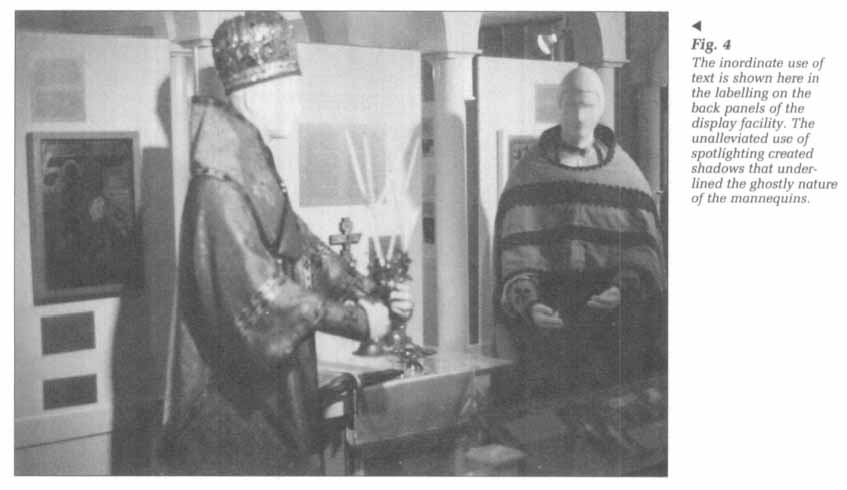

3 That Eastern Christianity has the potential of a blockbuster exhibit can be readily verified by perusing through such publications as the stunning Treasures of the Orthodox Church Museum in Finland (published at Kuapio, Finland, in 1985). Comparatively speaking, "Seasons" is artifact-poor. Furthermore, whether vestment, chalice, cross, liturgical cloth, icon or gospel book—all are downplayed in favour of texts. Throughout the exhibit, the objects on display are used as secondary, illustrative, explanatory material in deference to the exhibit's primary vehicle: text. Text panels, labels and related printed matter are paramount. The "catalogue" that was produced to accompany the exhibit is really a book and underlines the pervasive, two-dimensional bias encountered in this exhibit: the monograph not only functions independently of the exhibit (as a superlative introduction to Eastern Christian spirituality) but makes the exhibit almost redundant. (Indeed, the monograph has already been cited as a "portable exhibition" and examined from the theological point of view by Daniel Sahas of the University of Waterloo in the book review section of the authoritative Journal of Ukrainian Studies in its issue for the summer of 1987 on page 91.)

4 Since, as is implied above, "Seasons" shows a dearth of "treasures" (travelling exhibits are, in any case, notoriously hard on "priceless objects"), there is a natural tendency to compensate for this lacuna by using photographs and pretty-looking substitutes. These are usually contemporary in nature and succeed in depicting the continuity of this tradition in "the world of common experience ... children playing in water, lovers sitting on a park bench, a gardener working the soil" (from the introduction on page vi of the exhibit monograph). Occasionally, however, these efforts are less than successful; a plastic coil of garlic sausage nestled in an Easter basket, an icon of "Christ Pantocrator" adjacent to a wall-photo of a woman hoeing a vegetable garden—these are two examples that jarred this reviewer. Similarly, in its brave attempt to cover the entire spectrum of Eastern Christianity, the exhibit smacks of tokenism: vestments, for instance, are cited according to specific ethno-religious traditions (Ukrainian, Greek, Russian, Coptic and Mar Thoma), but few (if any) artifacts are dated or identified according to maker, provenance or other fields of museological importance.

5 Also, in acknowledging the "generous" financial and other assistance of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada, the exhibit and its "catalogue" can be faulted with insensitivity to the historical dimensions of religious factionalism within the Ukrainian community (the burning of churches by rival groups during the early decades of this century is a well-known "secret" among Ukrainian old-timers on the Prairies). Any inkling of partisan bias has been avoided in this ecumenical exhibit.

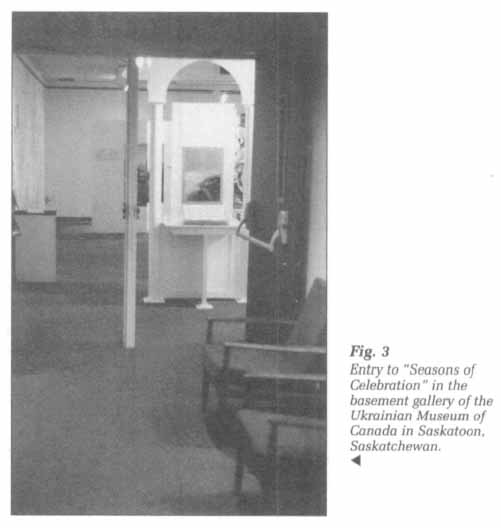

6 I was able to visit "Seasons" in two different locales in the course of its itinerary in 1987. In July I visited the exhibit in the basement gallery of Saskatoon's Ukrainian Museum of Canada; in October I saw the show again in Winnipeg at the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature. The Saskatoon installation seemed cramped (low ceilings are hardly conducive to spiritual uplifting); the same exhibition in Winnipeg's Alloway Hall was comparatively speaking more satisfying, thanks largely to the Hall's subdued lighting and the dramatic contrast provided by the white display units and the blackness of the Hall's exhibit space. Some of the labelling was obscure and difficult to decipher; gold lettering on a starkly white background, though striking, suffered in the unrestricted glare of spotlights in Saskatoon; and in Winnipeg textual matter on Plexiglas seemed to float and obstruct efforts to inspect the objects on display. Arches and archways constituted an imposing feature of the display facility; in Winnipeg some of these were used to invite the visitor to walk through/underneath but in Saskatoon they were used as barriers instead of passageways. Due to the unsuitable lighting used in Saskatoon, the faceless white mannequins clothed in liturgical vestments seemed ghostly in appearance; these were distracting and diluted the potential impact of displayed items on the visitor. Another irritation in Saskatoon was the background audio: bilingual (French/English) commentary over Slavic liturgical music; the spoken commentary was not always distinctly audible and could have been provided "on demand" via portable cassette or other mode of communication.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5Curatorial Statement

7 I conceived of the "Seasons of Celebration" project six years ago. It grew out of several concerns along with the direct interest in developing the exhibition: to examine the shape and meaning of cosmic ritual systems in the modern world, to establish an exemplary collection of the material culture of the Eastern Christian community in Canada and to develop the necessary documentary materials for the study of these cultures for the resource files of the Folk Life Program of the Provincial Museum of Alberta. The Museum Assistance Programme, National Museums of Canada, provided grant funding for an exhibition on the theme. I consulted with the various bishops of Eastern Christian churches, discussed the project and sought their blessing. This was useful despite the time involved. It paved the way for the necessary fieldwork in a great variety of communities, many of which are usually quite difficult for the researcher to access. During the second and third year I devoted a good deal of time to documenting the cycle of folk and ecclesial rituals, and to photographing, observing and interviewing people (clergy and laypersons alike). The meaning and shape of this ritual tradition, from the homeland through the Canadian period, was examined in all its richness. It is a singularly useful body of research, which I intend to work through and write on over the next few years.

8 It became clear during this phase of the project that the exhibition could be done, that it was possible for me to do it from a useful interpretive perspective and that it would receive a great deal of community support. With the assistance of my colleague Paul Beier, Chief of Design at the Provincial Museum of Alberta, we gave shape to the exhibition and opened it as scheduled in November 1986.

9 Few museums in North America have collections that reflect the religious material culture commonly used in Orthodox and Eastern rite Catholic communities. Consequently, it was necessary to use a combination of current and historical material (which in fact is how it works in the tradition) drawn from public and private collections. A collection of vestments and of holy hardware such as chalices, discoses and holy oil containers were acquired. Various service books in the multitude of languages from Armenian to Ukrainian, in editions worn by generations of use as well as those hot off the press, were hunted down. The ouvre of working iconographers was studied and samples acquired. Folk icons used by early settlers in the Canadian West and examples of common lithographs used in church and home were also prepared for use in the exhibition. Since Eastern Christianity is deeply rooted in a regard for nature's gifts, it was necessary to prepare the numerous breads and baskets used in the great feasts of the church year. The artifacts exhibited range from the contemporary to the antique, from those made on Holy Mountain (Athos) to the simple, humble objects fashioned with love by peasants at the turn of the century.

10 We strove to have the structure of the exhibition as an integral part of the theme and not merely a packaging of the ideas and materials. I emphasized this with Paul in our initial discussions. He achieved our aim by using an arch and column design with a white finish. The cruciform shape, central to the Christian tradition, emerged as the basic pattern of the exhibition.

11 Within the 139m2 space the cross pattern was accented by using red carpet to draw the viewer to the central core. The domed ceiling common to Byzantine architecture is hinted at in the structure by the use of arched columns throughout. This allows the rich fabrics, icons and hardware to be seen without the competing colour of the structure.

12 The exhibition consists of three major elements and an introduction. Visitors come to the triple-arch and column entry and are introduced to the tradition by the material on the two panels that flank the central arch. Passing through the arch, entering the sacred space, they are presented with material on Pascha (Easter), the event and rituals from which the liturgical tradition flows.

13 The first major element is a central kiosk with four winged panels. This provides the space in which "The Sanctification of Creation: the Divine Liturgy" is discussed. Each of the four sections has a primary focus and uses materials from a specific tradition: Greek, Russian, Coptic and Mar Thoma. The focuses are the Oblation (preparation of the Gifts), the liturgy of the Word, the Gifts, and the Communion. An audio-tape loop carries the interpretive text keyed to each section with an additional channel washing the gallery with liturgical music.

14 The second major element surrounds the core as a peristyle. Directly across from each of the four core vignettes is a triple-arch exhibit unit with a display case in the centre flanked by two panels. "The Sanctification of the Person: Rites of Initiation" is the title of this part of the exhibition.

15 At the four corners of the exhibition are winged panels containing an exhibit case, satellites circling the exhibition. The arch motif is present here as well. In these cases the theme "The Sanctification of Time: Feasts and Festivals" is developed.

16 Twenty years ago an Orthodox theologian preached in Rockefeller Chapel at the University of Chicago. Though I have forgotten his name now, I have carried the central image of his homily in my mind all these years: the spires of the church in the West point to the ultimate reality beyond this world, while the domes of the Eastern Church unveil the presence of the sacred in all God's creation. This wonderful image combined in my mind with the insight of the Cappadocian, Gregory of Nyssa, who saw the whole of creation as the play of God's energy.

17 Whether we are convinced of this view out of a modern ecological spirituality or from a mystical tradition that remains a part of our contemporary vision is perhaps unimportant. That the theology of the Eastern Church continues to articulate this view and that its liturgy still cultivates it is all important. It is to this pristine view of the world that the Church remains faithful.

18 The exhibition "Seasons of Celebration" reflects on the common action of the people of God, their action as co-creators of the cosmos. Gathering for worship they are engaged in the perfecting of the individual—indeed of all creation. This is the public work of the people of god.

19 My primary concern was to faithfully speak about this tradition's understanding of the meaning of human life. From the start it was clear that the Eastern Church saw the Christian revelation, not as an ideological system of ideas about the great questions and mysteries of our existence, but rather, as Jaroslav Pelikan (Sterling Professor of History, Yale University) says in the foreword to the book I prepared to accompany the exhibition, "Eastern Christianity has grasped, far better than has its Western counterpart, whether Roman Catholic or Protestant, how it is that this sacred history (the Christian revelation) unveils the sacredness of the natural world, indeed, of the total cosmos. Thus throughout the church year each sacred season associated with the biography of Jesus Christ is simultaneously a way to sanctify time, and each sacred ceremony a way of looking anew at the eternal and spiritual dimension in the temporal and physical realities of our existence."

20 I was very concerned that "Seasons of Celebration" would end up as another in the long line of ethnographic exhibitions isolating the world of meaning under consideration from the experience of the general viewing public. This would have been particularly dreadful because Eastern Christianity is not one which suggests there are two worlds: one sacred world of canonical ritual and the other our shared profane experience. There is only one world of human experience and the ritual tradition speaks of the fulness of its meaning.

21 To address this we used large backdrop photographs of common human activity typologically linked to each ritual. For example, a photograph of several children playing with their father in a lake was shown to introduce (bridge) the Mystery of Holy Baptism. The narrative text begins, "Since the beginning of time human beings have used water for washing, refreshment and recreation. Christian baptism gives form to this human desire. It is a form of re-creation. The new born child or adult is re-created in the image of God." Judging from the fine response to the exhibition this seems to have worked. Visitors to it are inclined to linger, examining the material and its suggestion about just what it means to be living in a world full of joy and sorrow.

22 "Season of Celebration" has made it possible to establish a fine collection of artifact material as it garnered the confidence and favour of Canadians whose origins reach back to Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa and India. The collection continues to grow. With the fine cooperation of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies and the University of Alberta I was able to dovetail "Seasons" with a major international conference on the Ukrainian religious experience. I planned the book and commissioned chapters from appropriate scholars. Around the conference table we read and discussed each others work. The volume will be published for the millennium of the Christianization of Kievan Rus' this year.

23 Activities such as lectures, workshops, feature exhibits, and performances have been planned by the various museums hosting "Seasons." Opportunities to contribute to scholarship in the area have abounded. But what is most satisfying about the "Seasons" project is what every field researcher experiences: a glimpse at the marvelous way human beings move through the seasons of life and their insatiable delight in celebrating them.