Research Notes / Notes de recherche

History Painting:

The Creation of Interpretive Tableaux

1 "History painting" used to rank at or near the top of the arts. The most highly praised canvasses were those that depicted scenes from history, paintings that had a narrative message or moral. Such works might show a distant past that was lost in the swirl of time, or more recent events that had significance in the context of a particular state or dynasty. In the eyes of France's Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (founded in 1648) history painting was the highest genre, followed by portraiture, the still life and then the landscape. Put briefly, history paintings earned their top ranking because of their content. Art historian Pierre Rosenberg explains: "The quality most prized in an artist was his imagination. Is it not more difficult to portray this saintly miracle or that heroic deed ... [or] this Biblical episode or that passage from Ovid, than it is to paint a few apples or a dead jack rabbit?"1 The foremost mid-eighteenth-century art critic, La Font de Saint-Yenne, made the same point, only in more poetic fashion: "Le peintre historien est le seul peintre de l'âme, les autres ne peignent que pour les yeux."2

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 Although history painting was a single genre, appropriate subject matter ranged widely. Such works could be didactic or allegorical, commonly handling themes from Greek mythology, Roman history or the Bible. The genre also included canvasses that dealt with more recent events. Great moments, like a coronation or a battle, were considered worthy of recording and commemoration.

3 The days of history painting as an art form have long since passed, supplanted by the romantic and individualistic concepts of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Art today—"true" art we are told—is supposed to be a personal statement, an exploration of one's individual creativity. History painting, old-fashioned and out of favour, has become but a trade. Its practitioners are no longer thought to be artists, at least by the art establishment. Rather, in a culture that values originality and novelty—"newness"—above almost all else, they are considered mere illustrators.

4 Despite its exclusion from the modern art world, history painting lives on, and nowhere is it more visible, or more popular, than in the museum and historic-site community. The classical allusions and sacred themes may be gone, but the idea of using art to serve some overriding "purpose" certainly has not disappeared. Those who commission today's history paintings call them a means of interpretation,3 yet it would be naive not to recognize that such commissioned work often serves much the same purpose as its seventeenth- and eighteenth-century counterparts. Namely, it reflects and promotes the particular political and social context from which it arises. (As an aside, literature can perform much the same role. Witness Shakespeare's history plays, in which the bard embellished the reputations of the early Tudor monarchs and tarnished those of the Plantagenets.4)

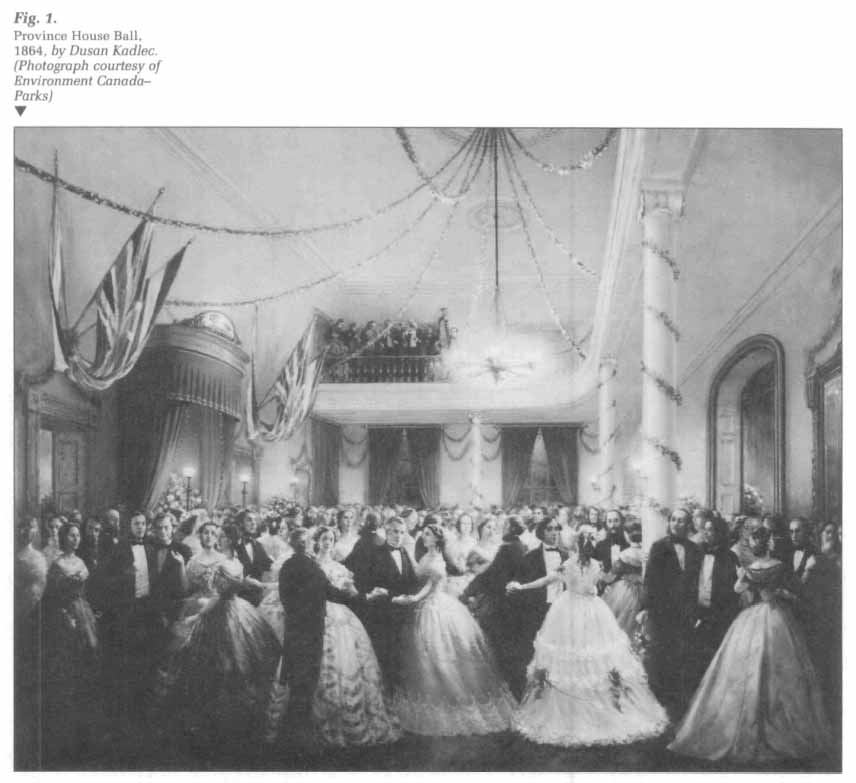

5 An example of how today's history painting can reflect its context is Dusan Kadlec's very fine 1982 painting of the Fathers of Confederation dancing at an 1864 Charlottetown ball (see fig. 1). Here is a work of definite achievement, one that displays both Kadlec's considerable talents and those of a team of Parks Canada specialists who provided the painter with a richness of curatorial detail. The end result for the viewer is a charming composition that warmly and evocatively recreates a gala evening known to have taken place in 1864. One could ask, however, in the same way that one asks such questions about art and other objects from the past, why does this painting exist and what does it tell us about the era that produced it? The ball itself was without historic significance, and therefore one might argue the canvas is without a raison d'être. Yet the painting was commissioned (the work was a gift of the Themadel Foundation, St. Andrews, New Brunswick), and it obviously served an intended purpose or met some need during the early 1980s.

6 According to the most recent description of Kadlec's Province House Ball, 1864, the work was created to show "visitors a more glamorous aspect of the historic meeting as a pleasant contrast to the serious image of our Fathers of Confederation around a conference table."5 Clearly, therefore, this particular painting, in its own soft-sell kind of way, was seen as promoting federalist objectives relating to national unity, a topic of paramount importance at the time the work was commissioned, in the midst of the debate over "sovereignty-association." And so it was two and three hundred years earlier, with the history paintings of the baroque period. Only the belief systems, states or regimes that are being promoted through the genre have changed. History painting, like historical writing, is rarely if ever value free.

7 The greatest name in Canadian history painting thus far has been Charles W. Jeffreys (1869-1951).6 Jeffreys was born in England but emigrated to Canada with his family in 1880. In the years that followed he became his adopted country's foremost painter and illustrator of its history. With murals, canvasses and books (most notably The Makers of Canada and The Picture Gallery of Canadian History)7 Jeffreys created works that had broad interest and support. Corporate clients and schoolchildren alike responded to his depictions of stirring moments in Canadian history: the founding of a city, an explorer's arrival, a military victory. These were the topics that appealed both to the artist and to the audience of the first half of the twentieth century. In addition to reflecting that era's concern with capital "H" history, the story of great men and great events, it must also be said that Jeffreys showed a highly developed interest in the architectural and material culture history of Canada's early days. A cursory glance through The Picture Gallery of Canadian History offers proof enough.

Display large image of Figure 2

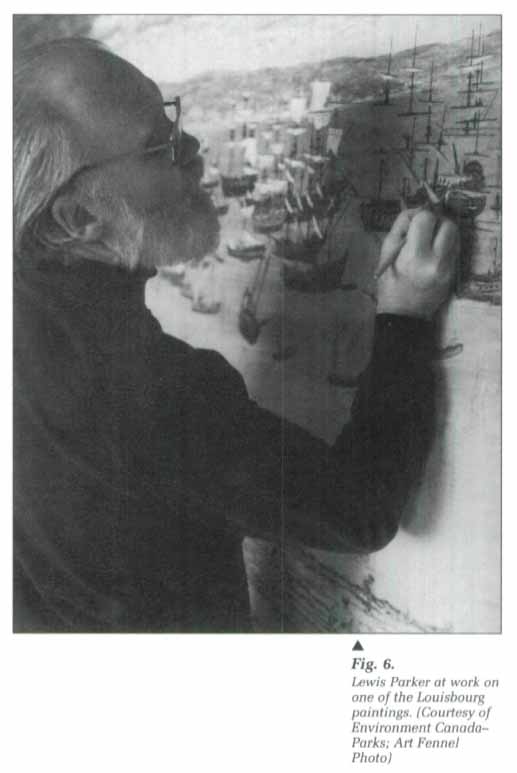

Display large image of Figure 28 Perhaps the best known of C.W. Jeffreys' successors is Lewis Parker.8 Born in Toronto in 1926, Parker moved from an early career as a newspaper cartoonist and book illustrator into what was for him the more satisfying world of history painting. His early accomplishments in the genre, at which time he was partnered with Gerald Lazare, included a series of paintings for Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons, illustrations for the National Film Board and murals for the National Museum of Man (now the Canadian Museum of Civilization). Their specialty for many years was native people, particularly the Inuit and the Hurons.

9 Since the mid-1970s Parker has worked without a partner. During this time he has concentrated on the history of Atlantic Canada, completing a number of projects first with Parks Canada and then with the University College of Cape Breton. These works provide a case study of the history-painting genre as it stands today. Of particular interest to readers of this journal should be the emphasis that is currently being put on the need for accuracy in the material culture aspects of such compositions. The paintings themselves, of course, are significant cultural objects in their own right.

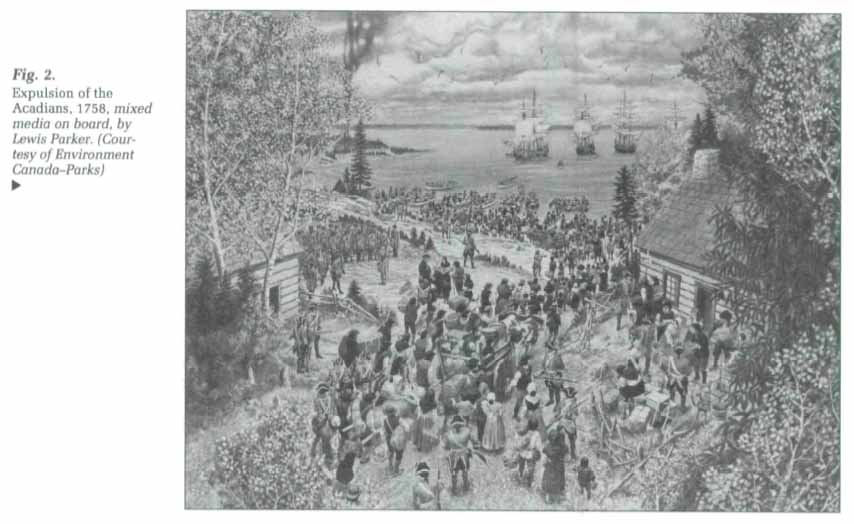

10 The first painting Lewis Parker did for Parks Canada was a scene (see fig. 2) depicting the 1758 expulsion of the Acadians from île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island). The illustration was commissioned specifically to be used in a film presentation for Fort Amherst National Historic Park, with close-up photography being envisioned for virtually every corner of the painting. Accordingly, great care was taken to make sure that anything that appeared in the composition could be documented to be correct, from costumes to house construction details to the packages being carried away. Parks Canada historians, curators and interpreters gave Parker the information he needed; the artist did the rest. The end result is a poignant scene, with hundreds of Acadians slowly descending to their fate. The composition has drama, and yet how different it is from earlier depictions of the Acadian deportations and from history paintings of the baroque period where the moral was the message.

11 In Parker's and Parks Canada's version of the Acadian story there is no central figure or figures. Instead, the artist has come up with a composition consisting of a serpentine exodus of a mostly faceless people. This is the element that commands the eye's attention. These Acadians are being expelled by soldiers just doing their duty. There are no heroes, no villains, no tragic separation of lovers from each other or parents from their children, no real suffering; although if we know our history we read all this into the scene. To the surprise of a classical history painter, could one but see the work, there is no allegory and no symbols. This is literal history, as it may well have been. Praiseworthy, certainly. The composition selected, however, does meet another objective. It is neutral enough on emotional grounds so that no modern Canadian, from either of the two main linguistic communities, could find any reason to object to it. In that sense, the painting reflects the socio-political context in which it was painted.

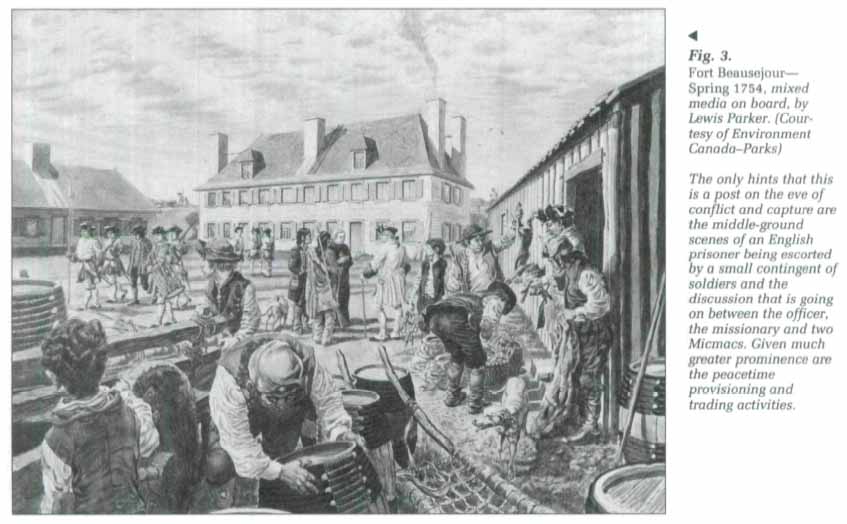

12 Lewis Parker's next project with Parks Canada was to execute a series of eight paintings depicting Fort Beausejour/Fort Cumberland (at Aulac, New Brunswick) as it had once appeared. When completed the paintings were then photographed and used as ground interpretation panels at the park. A decade earlier, when budgets were more flush and reconstructions were in vogue, consideration might have been given to actually rebuilding and refurnishing the old fort. In the leaner years of the late 1970s, however, that kind of development was not an option. Pictures are not only worth a thousand words, but they also cost thousands less than the real thing.

13 The eight paintings (all mixed media on board) were to show what Fort Beausejour/Fort Cumberland might have looked like during the Seven Years' War (when it was captured by the British from the French) and then at the time of the American Revolution (when it was attacked by a contingent of Americans). These conflicts were the reasons why the site was considered to be of national historic significance. Yet here again the decision was made not to illustrate hostilities. Preparations for war are shown, but no actual conflict. Instead, Parker was commissioned to create works that visually reconstructed the buildings of the fort, complete with people and a range of material culture objects. The resulting compositions have unity and strength (see, for example, fig. 3). Yet how they might puzzle patrons from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Where are the battles? where are the victors? they might ask. The answer of course is that our generation's focus is not on victory or defeat. It is on celebrating the Anglo-French reality of the country. It is an exploration of how people worked and lived, not how they fought and died. Consequently history painting has generally become social history, with an emphasis on curatorial detail.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

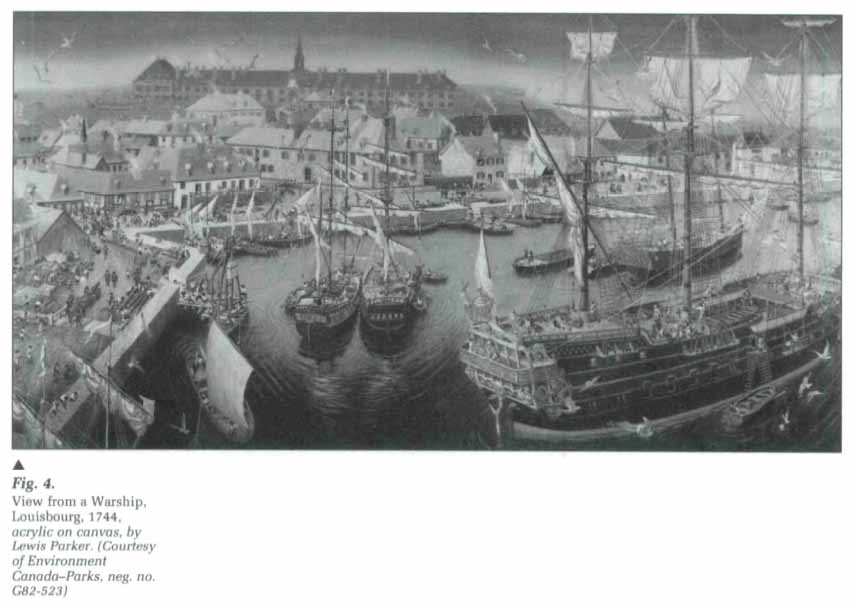

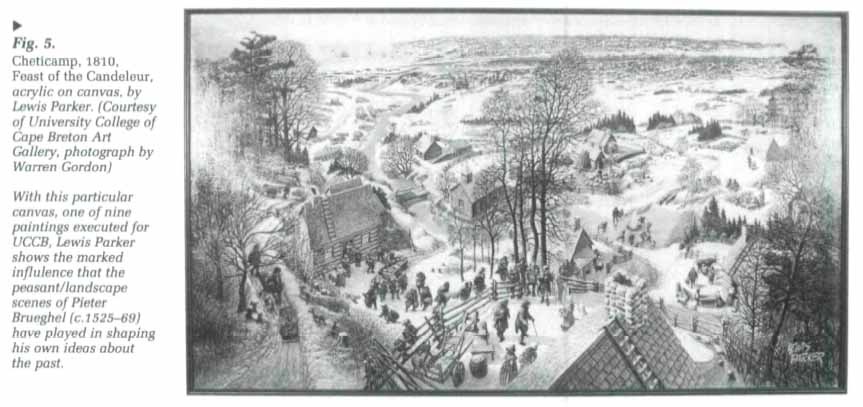

Display large image of Figure 414 Lewis Parker sees his best work in a quite different context. While he strives for all possible accuracy and relies on specialist advice for details, he thinks some of his canvasses offer more than a simple illustration of bygone life-styles and technologies. History paintings though they be, he believes that some of his works fall squarely in what he calls a humanist tradition. Parker harkens back to the canvasses of the great Flemish artist Pieter Brueghel (c.1525-69). He likes to think he is following in Brueghel's footsteps.9 Certainly there are parallels. Where Brueghel depicted rich, at times almost encyclopaedic, scenes of peasant life, Parker has attempted to do the same in his most recent work for the Fortress of Louisbourg and the University College of Cape Breton. Here are canvasses (see figs. 4 and 5) that set out to cover much the same ground as Brueghel's. Portrayed is the world of ordinary people, adults and children, at work and at play, not just a single activity, or a particular corner of a specific fort. Instead, the settings tend to be sweeping, and there is a desire upon the part of the viewer to interpret what they are seeing as a microcosm for a wider society.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 515 Many of the basic elements that dominate Parker's recent paintings—the "choreographed" vignettes, the frequent use of children, the play of light and nature's forces— were present in his earlier works. But of late they have come more to the fore. Inspired by Brueghel, and given greater artistic freedom by those who commissioned the latest canvasses, Parker has come up with compositions that are much more ambitious than his early efforts in the genre.

16 Lewis Parker has written that his paintings are like a love affair. The details may be "troublesome," but the "whole is cherished."10 What is that whole, one might ask? On one level it is a particular composition, a depiction of this fort or that community at some point in its imagined past. But there is of course another level of meaning, a meaning that goes beyond the literal scene to the essence of the work. On this level, I believe, Parker's latest canvasses fall within the tradition of classical history painting. For while the stories he depicts are not like those of the past (but are the product of today's social and political contexts), there is nonetheless an overriding moral sense to his work that is like that of the great masters. Like them, he has an ordered vision of how societies ought to work, and it is that vision that guides his paintbrush. Lewis Parker presents societies as they should be, or rather as they should have been—with people in motion, tasks being accomplished, everyone busy and lives unfolding as they might. It is an idealism that goes beyond the didacticism essential to such illustrations. It is instead a philosophy of life, a humanist outlook, that he presents, a perspective on the dignity of work and ordinary people that he shares with Pieter Brueghel. It is indeed a moral philosophy that shapes Lewis Parker's paintings and allows him to transform the myriad little dramas of past lives into his own distinctive art form.

17 To conclude, for students of material culture the history paintings being created today by people like Lewis Parker deserve attention for two reasons. First and most obviously, they are objects of significance in their own right. They are educational in intent and tend to lay great stress on "curatorial" details. In many instances, the museums and historic sites that commission them do so because it would either be too difficult or too expensive to physically re-create the events and objects the institutions want to show. Second, and just as important, it must be recognized that these creations are just that: intentionally or unintentionally they reflect the concerns and aspirations of those who commission them, as well as those who execute them. Like historical writing, history painting is always coloured by its context.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6