Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

In Search of Early Canadian Embroidery Abroad

I have received the beautiful articles you had the kindness to send me. They are certainly most acceptable in themselves being the work of skilful and tasteful hands; but these gifts are especially precious to me on account of the feeling that has dictated the offering...

Murray.

London, April 23, 1767.

1 I suppose that it was really these two simple references, one from Marius Barbeau's small book on religious embroiderers in Québec entitled Saintes Artisanes1 the other, a letter reprinted in the Ursuline Sisters volume Glimpses of the Monastery,2 which prompted me to begin this exercise. In the twelve years that had passed since I had begun my research into the embroidery collection of the Ursulines of Québec, I had concentrated almost exclusively on those works that had remained inside the walls of the convent itself. In fact, I rarely allowed myself to consider what works were to be found outside the seminary, so vast was the body of artifacts and information within. More recently, however, inspired by such references, I sought to explore various collections and research themes pertaining to early Canadian embroidery abroad, and accordingly, this is a report of fieldwork in Great Britain.

2 From all of my reading of the volumes of primary sources available in the Ursuline Archives and from published materials, I was aware that the Ursulines had supported their convent and girl's school from its beginning in 1639 through the sale of liturgical embroideries commissioned by the various parishes in Québec and indeed all along the shores of the St. Lawrence River. It was a practice that the Ursulines continued as long as there was a demand for their superbly designed and fashioned ecclesiastical works. However, in their desire to produce as much as possible in order to meet the ever-increasing financial demands of their missionary duties, the inventive sisters also identified a market that could be supplied with items of a more secular nature. It may have perhaps begun with the collection and production of some of the pieces mentioned by Barbeau, to be sent to the young Dauphin for his edification, and continued through the arrival of the British in the mid-eighteenth century, until the production of such items became less economically necessary and was taken over by workshops outside the walls of the cloister.3

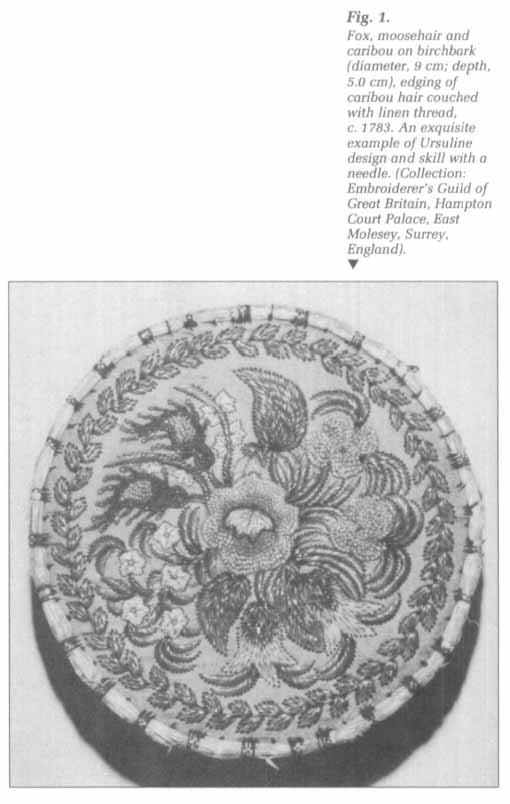

3 These works, according to Barbeau, were fashioned "dans le goût des Sauvages," which, translated loosely, might be described as "in the style of the natives." The materials were all locally available from nature and in that respect meant that the funds garnered were all profit. Primary among these materials were animal hides, birchbark (a good substitute for leather or cloth), moosehair (a thread as fine as silk which could readily be dyed into glorious hues using locally available plant dyes) and finally porcupine quills (somewhat more difficult to work with, but useful nevertheless in these types of handcrafts). The products tended to be trinkets of high quality, such as boxes, picture frames, fans, baskets, wall panels and other easily transportable items aimed at the tourist trade. In addition, traditional materials such as silk cloth and thread were used when the profits to be made justified this expenditure. In 1792, Mrs. John Graves Simcoe described this work in an account of one of her visits to the convent at Québec:

4 A search through the annals and various other documents relating to the general history of the Ursulines revealed a number of related areas for investigation. Of primary interest to me was the fascinating relationship of the "powers that be" in the French regime to the Ursulines. This, I felt, was easily understandable. The nuns were regarded with great esteem in New France, being the sole source of education available to the daughters of the elite in the early years of the colony. As such they were supported and visited by anyone of importance who came to New France and consequently exerted a great influence in the life of the fledgling nation. However, this influence and indeed prestige in the community continued on into the English regime, through the latter half of the eighteenth century and on into the nineteenth, despite the obvious difference in religious adherence. With the British regime, this relationship took on a more formal tone. Fascinating accounts of these very dignified encounters are given throughout the latter portion of Glimpses.5

5 An integral part of this relationship, no matter how formalized it had become, was the giving and receiving of gifts and the purchasing of items of interest from the nuns as a way of providing financial support for the school. Despite differences in religious affiliation, many senior British officials continued to send their daughters to the Ursulines to be educated, considering the convent's schooling to be the best available. It was an exploration of this formal relationship with the ruling classes that I felt would yield the most interesting sources for the kinds of artifacts which I hoped to uncover in Britain.

6 To be more specific, I wrote to the Canada Council requesting partial funding to pursue, in Great Britain and in France, those items fashioned of cloth and thread that I felt sure would have returned to Europe in the possession of persons of importance. I was uncertain as to whether or not I would be able to uncover large numbers of these Ursuline items but felt that this was an aspect of the history of the collection which could not be left as a stone unturned. However, to provide a broader context in which to work and a more substantial result than the strictly "Ursuline" work would permit me to survey, I decided that I could just as easily focus on early Canadian embroideries in general and hopefully gather information that would be of interest to a broader range of people. (Here I had those interested in Canadian embroidery history especially in mind.) Happily, the Canada Council agreed.

7 With the help of friends in the museum field, history books and other printed sources such as DeBrett's Peerage, I was able to come up with a substantial list of individuals and institutions who might assist me with my search. As an example, key among those who regularly visited the Ursulines cloister through the British regime were the governors general. Using this as a starting point, I was able to come up with a list of heirs living in Great Britain who might still have the treasures I was seeking in family collections. In writing to all the institutions and individuals I had identified, I made it clear that I was not interested in the repatriation of these items, simply in recording their existence and documenting their relationship to early Canadian artisans.6

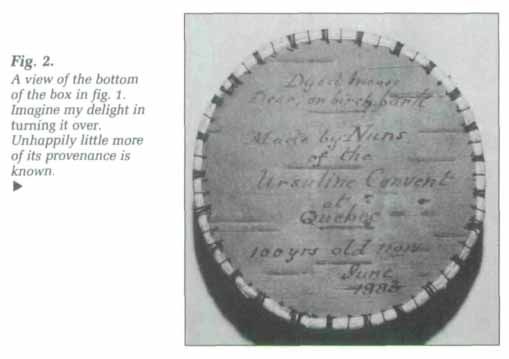

8 The results of my enquiries to individuals proved disappointing. Almost without exception, they wrote to say that they were unaware of any such items. The museums contacted were much more encouraging and agreed, in most cases, to grant me access to their files and, wherever possible, the actual artifacts in their collections. As I felt this was a sufficiently positive response to allow me to fulfill the terms of my grant, I forged ahead with the project. What precisely I might find in these collections was an unknown factor, and indeed, turned out somewhat differently than I had expected.

9 The first surprise to greet me on arrival in England was of the most inconvenient kind. A strike of channel ferry workers made travelling to France virtually impossible, as alternative transport was almost totally booked. Even if I could have gotten to France, getting back to meet the obligations of my tightly organized schedule would be difficult. For example, the date of a major speech to the Annual Meeting of the Northern Branches of the Embroiderer's Guild of Great Britain could not be altered, nor could the times of appointments with various British museums, where curatorial help had been organized. Unhappily, the cancellation of my trip to France had possibly eliminated the first hundred years of my time frame, not to mention the opportunity to uncover some of the earliest Ursuline works. This aspect of the project has been rescheduled for the spring of 1988 and will fill, I hope, some of the gap created by those unobliging ferry workers.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 210 In Britain, however, my fortunes were brighter. I visited six major collections and was able to come away from five of them with photographs and documentation for a wide range of early Canadian works.7 The surprise for me (though I suppose had I thought it through at greater length need not have been) was that almost everything I had seen was in the "native" style of embroidery. The one or two exceptions were contained in the collection of the Embroiderer's Guild of Great Britain housed at Hampton Court Palace. One other piece not in the native style, a canvas work done by the "ladies of Montreal,"8 was identified in the collection of Lord Elgin, a direct descendant of our thirty-seventh governor general (1847 to 1854). Regrettably, at the last moment, this piece could not be viewed because it had been packed away for a move and could not be found. Such are the joys of research.

11 With only those few exceptions I began to uncover a whole body of work to which I, as an embroidery historian, had previously paid little attention, being so wrapped up in the first grand works of the Ursulines, then going forward in my research through the centuries to the samplers, Berlin work and other embroidered fascinations of Victorian Canada. Needless to say, I was more than a little overwhelmed. Fortunately, while beginning my work at Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University, I came upon the monograph by Geoffery Turner, written in 1955,9 which provided me with a definitive base from which to view most of what I was being shown as "Canadian embroidery." Also, I had the good fortune to visit with Margaret Swain of Edinburgh whose article on moosehair embroidery clearly puts that so-called "craft" into the realm of "embroidery as art."10

12 Among the items of greatest interest to me were, of course, a select few that dealt particularly with the Ursuline collection. Of those, one is illustrated with this article (figs. 1 and 2). It would be difficult, within the bounds of this research report, to itemize all artifacts that I viewed and photographed. However, they included moosehair and quill work from many parts of the country, collected primarily by visitors and passed on in families to finally be donated to museums. There was also a large body of beadwork, including moccasins from many tribes and locations and accessories such as pouches, knife sheaths and mittens worked in various designs. Each of these items was important to me as an embroidery historian, but this project has opened a Pandora's box, full of anthropological and ethnological considerations for which I admit to being unprepared. It is an aspect of my work with the Ursuline collection which will now take me some time to sort out, given the multi-disciplinary nature of the subject.

13 In the meantime, however, by the summer of 1988, I will provide the Canada Council with a set of slides and accompanying notes dealing with those items that I have found in British and French collections. Particular emphasis will be accorded those pieces fashioned of cloth and thread, or perhaps birchbark and moosehair, which form such an integral part of the development of the art of embroidery in early Canada.11