Reviews / Comptes rendus

Environment Canada, Parks Canada, Christ Church Cathedral, National Historic Site: 1983

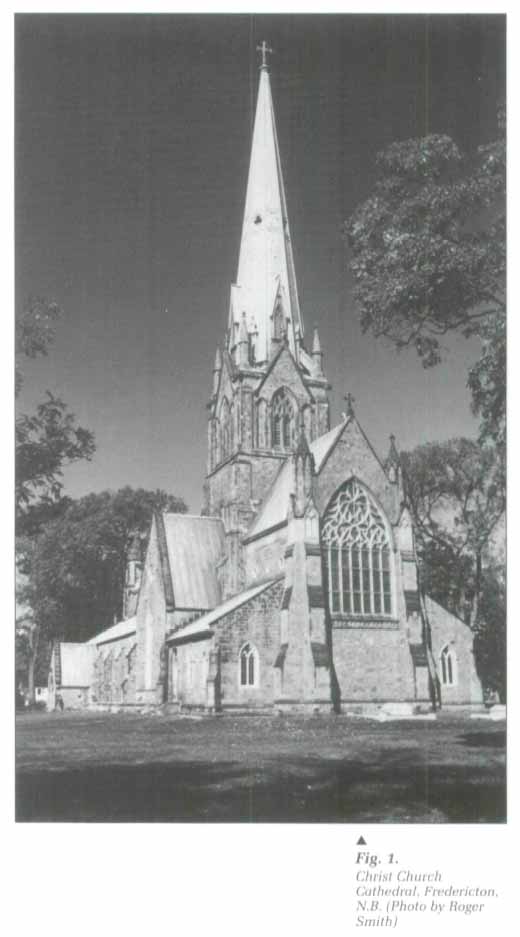

1 Fredericton's Christ Church Cathedral was designated a National Historic Site in 1983 for its historical and architectural significance. Structurally, it is considered one of the best and earliest examples of Gothic Revival architecture in Canada. Yet, looking beyond the obvious architectural aspects of the building, one will find an exhibition rich in social history.

2 The cathedral was constructed between 1845 and 1853 under the guidance of the first Bishop of Fredericton, the most Reverend John Medley. Plans were prepared by architect Frank Wills and approved by the Ecclesiological Society of England. The original design was modelled after the fourteenth-century Parish Church of Snettisham in Norfolk and incorporated features from several English churches. Since its consecration, the cathedral has continued to develop through minor additions and alterations reflective of the community values and cultural heritage of New Brunswick Anglicans.

3 Some may hesitate to consider a place of worship as a museum-like exhibition in the traditional sense. For example, there is no identifiable curator who has researched and presented a single thematic exhibition, but rather many "keepers" who have made numerous contributions over the years to an ever-evolving presentation. Perhaps a museum of this type could more appropriately be considered an ecomuseum. As defined by the International Council of Museums in 1971, the ecomuseum concept would seem to apply to this exhibition:

With this approach, the exhibition authors and spectators are not differentiated.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 Christ Church Cathedral certainly qualifies as an exhibition within the broadest sense. It represents a display of objects arranged and assembled for the purpose of communicating with an audience: to inspire, to inform and to convey a concept. It also fulfills basic exhibit objectives as outlined by Thomas Schlereth, to stimulate historical interest, promote historical thought, convey a sense of historical interest, encourage historical thought, convey a sense of development and establish a historical context.2 It is not through coincidence that these objectives are met, but rather as a result of careful, thoughtful decision making on the part of the cathedral community.

Display large image of Figure 2

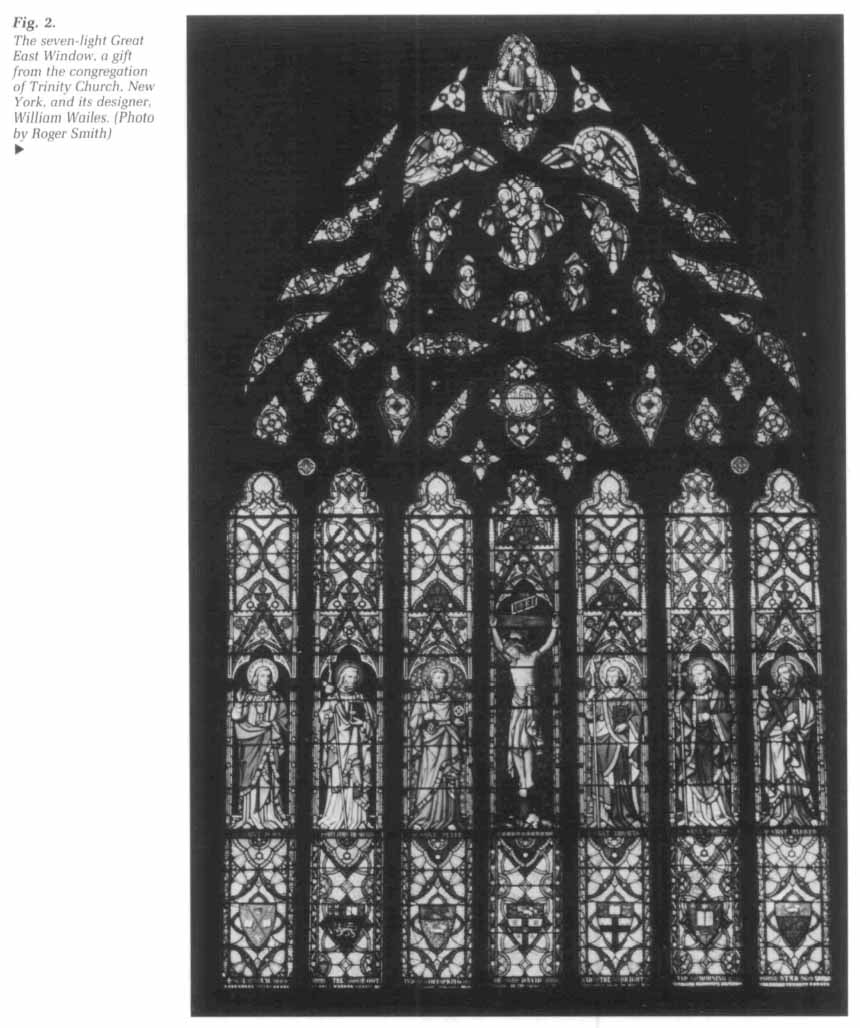

Display large image of Figure 25 In terms of design, Christ Church Cathedral is an architectural gem. It is an outstanding example of middle-pointed or decorated Gothic and is noted for its fine stained-glass windows. The four small west windows in particular are believed to be unique in Canada for the gold work they contain.3 The highly decorated interior woodwork and pews are of native butternut. In the chancel, the walls are painted in the Gothic style with Christian motifs and biblical mottoes. The seven-light Great East Window, over the high altar, was a gift from the congregation of Trinity Church, New York, and its designer, English artist William Wailes. Incorporated in the window design are the coats of arms of the seven British North American Anglican dioceses in existence at that time: Toronto, Québec, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Rupert's Land, Montréal and Fredericton.

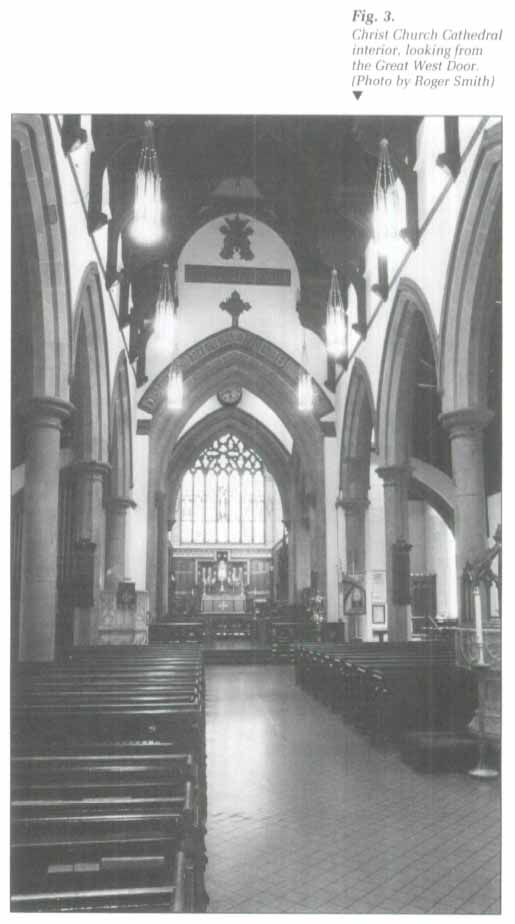

6 As the visitor enters the Great West Door of the cathedral, the interior arrangement presents itself. Immediately one is drawn by the power of the artifacts to communicate, and to stimulate contemplation about their meaning. A brief guide to the building is available at the entrance, as well as a colourful historical publication by Robert L. Watson. These provide the visitor with the necessary details and background information. Exhibit labels are presented in the form of commemorative plaques which are incorporated into the design of many of the artifacts.

7 It is difficult to isolate the purpose of this exhibition, for it is very complex. As a tribute to the Glory of God, the intent is to inspire the individual and to evoke a spiritual experience. Upon entering the building, the power of the interacting artifacts is undeniable, regardless of one's religious beliefs. Almost immediately the viewer is filled with a sense of awe and curiosity. Yet, after the initial impact, one is struck by a secondary awareness—that of the passage of time, a pattern of development, continuity from one generation to the next and a community moulded by circumstance.

8 When Bishop Medley arrived in the newly formed diocese of Fredericton in 1845, he brought with him the plans for the new cathedral church. This was to be the first entirely new cathedral on British soil since the Norman Conquest and the first built in the Anglican community after the Reformation. As a "Mother Church" it was to represent an ideal image of the established church in British North America, exemplifying a unification of church and state. Ultimately it was intended to set a standard for an entire social order. Bishop Medley was very much aware of this. The design of Christ Church, both exterior and interior, represents a powerful statement—the result of careful planning.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 49 Through the years following its consecration, several alterations were made by succeeding generations. Many of the changes to the interior, which took the form of tributes to the Glory of God or memorials to those who died, are visibly apparent. These objects evoke a sense of faith and inherited responsibility, reminiscent of the lines from a familiar poem:

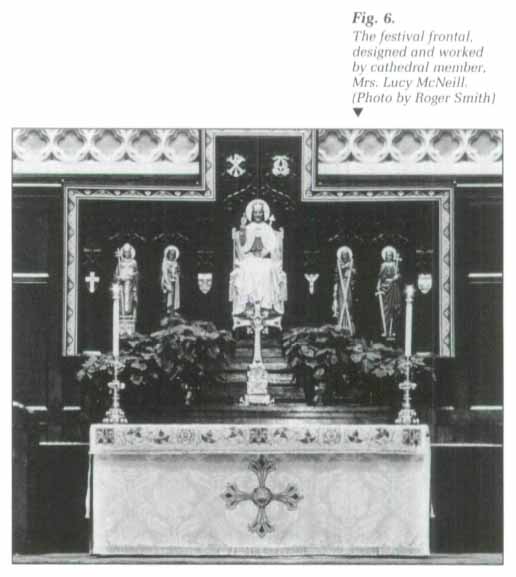

10 The artifacts displayed represent significant events in the lives of those involved. Despite the fact that these objects are not arranged in chronological order, a line of social development and continuity still becomes evident, linked by a common element of faith: faith in god, faith in the state, faith in the past, faith in the present and faith in the future.

11 Beginning with the memorial tablet to Major General George Stracey Smyth (Lieutenant-Governor of New Brunswick from 1817 to 1823), located in The Lady Chapel, the pattern of development unfolds.5 The long inscription refers to the faith Major General Smyth held in the sovereign, the church and the "rising generation." There is also a reference to the lieutenant-governor's "humane attention" to the welfare of the "captive and oppressed Africans" of New Brunswick.

12 Outside the chapel, in the south aisle, lies Bishop Medley's life-size effigy—a striking reminder of this man's lasting presence. The marble carving was executed by Bacon Brothers of London, England, and is said to be an exact likeness. Dressed in his episcopal robes and holding his pastoral staff, he appears to be at rest, confident in the succeeding generations. As further evidence of Medley's lasting influence, his cathedra (or throne) — a modest design at the bishop's own request— occupies a corner to the left of the high altar. The current Bishop of Fredericton, the Most Reverend Harold Nutter, has been quoted as saying: "Medley, in some ways, is still the Bishop of the Diocese."6

13 A memorial to members of the cathedral congregation who died in World War I is displayed on the south wall of the choir. Modest in design, it consists of a small plain cross constructed from stones recovered from the ruins of the cathedrals at Arras and Ypres by the Right Reverend John A. Richardson, third Bishop of Fredericton, in 1918. As artifacts, these stones serve as physical evidence of the destructiveness of war and link us with those who died for their country.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 514 Over the west entrance to the cathedral hang the flags of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, the Royal Canadian Air Force, the 1st Battalion York Militia and the World War II Minesweeper HMCS Fredericton. They vary in age and degree of deterioration and hang in testimony to time and continued faith in the state. The oldest are the King's Colours and the regimental colours of the 1st Battalion York Militia, presented by Lady Campbell (wife of Lieutenant-Governor Sir Archibald Campbell) in 1835. This battalion, made up of local citizens, was formed after the American Revolution as a defensive measure within the newly established colony.

15 Small items pertaining to the history of the cathedral are displayed in a case at the back of the building. Through these objects one is made aware of the impact of the cathedral's presence on the people of Fredericton. For example, among the items presented is a copy of the Letters Patent declaring Fredericton a Cathedral City by Royal Decree in 1845. Before the cathedral could be constructed, it was necessary that Fredericton become a city (despite its modest number of residents). Also displayed is a piece of fused metal from the original cathedral bells, which were destroyed by fire caused by lightning in 1911, and samples of the miniature bells struck from the original bell metal and sold to assist in financing the subsequent restoration.

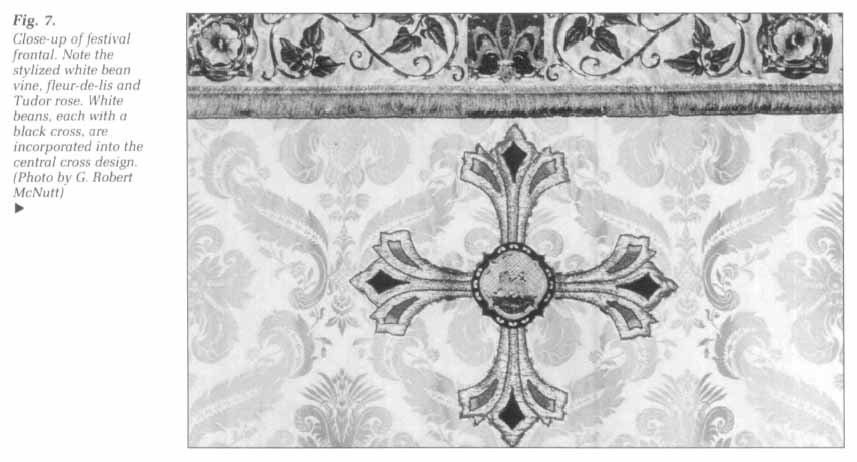

16 Representing one of the more modern additions is the festival frontal, used to decorate the high altar during special occasions. This fine piece of needlework was designed and completed by cathedral member Mrs. Lucy McNeill in 1964 and combines symbolic images of Fredericton's past with Anglican tradition. Present in the design is the fleur-de-lis (symbolizing the first Christian worship), the Tudor rose (symbolizing the United Empire Loyalists who settled here) and the white bean with vine (symbolizing a local story concerning the Loyalist settlers who were saved from starving by wild white beans planted by the previous Acadian settlers). Through these images one is reminded of the particular historical circumstances from which this cathedral has developed.

Display large image of Figure 6

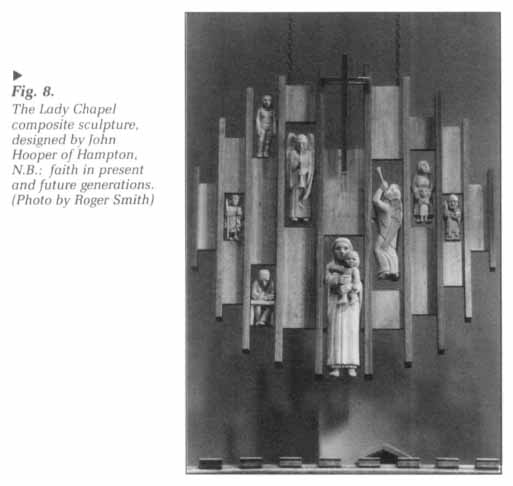

Display large image of Figure 617 Even more recent is The Lady Chapel, installed in 1980. Dominating the chapel space is a modern composite sculpture designed by John Hooper of Hampton, New Brunswick, indicative of the cathedral's link with the present and continued faith in the future. Contained in the sculpture are stylized figures of the Blessed Virgin (to whom the chapel is dedicated), the Risen Lord, a scholar (representing the Arts and Literature), a teenager (indicating that the future of the Church rests with the youth), angels blowing trumpets (representing the joy of music in the church) and a woman leading a child (illustrating the source of inspiration through example). These images reflect the current values of the Anglican Church, as they relate to the present generation and the future.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 818 One might say that the exhibits within the cathedral are arranged in accordance with the traditions of the Church, having developed through a long process of social evolution. Every object serves a common purpose: to promote thought. No space is wasted, and every element has meaning, explicit and implicit. As a whole, Christ Church Cathedral is the product of a community touched by events throughout history. It stands as a memorial to the people who created it and their passage through time. The past is linked to the present, thus providing material evidence of a community's social history.