Reviews / Comptes rendus

New Brunswick Museum, "Reflections of an Era: Portraits of 19th Century New Brunswick Ships"

CATALOGUE EDITOR: Paul Castle.

TRAVELLING EXHIBITION: January 1987 - August 1988.

TOUR: Newfoundland Museum, St. John's; Le Musée du Québec, Québec; Mackenzie Art Gallery, Regina; Northern Life Museum and National Exhibition Centre, Fort Smith, N.W.T.; Art Gallery of Hamilton; New Brunswick Museum, Saint John. Reviewed at Musée du Québec.

ISBN 0-919326-25-0.

1 Over the years, and particularly during the 1950s and 1960s, the New Brunswick Museum has built a fine collection of nineteenth-century ship portraits. A large number are oil paintings, but there are also watercolours and gouaches. Many were given to the Museum by descendants of the shipbuilders, masters or owners for whom they were painted; some were wisely purchased as the opportunity arose. The Museum has reason to be proud of the quality and extent of the collection for it truly reflects the vigour of the province's nineteenth-century shipbuilding and shipping industries. Quebec would be happy to boast as fine a reminder of her shipbuilding days.

2 Understandably this collection was considered worthy of special display, and financial support for the exhibition was obtained from several sources, mainly the Museum Assistance Programmes of the National Museums of Canada, for the necessary research on ship portraiture in general and the New Brunswick Museum's collection in particular, to be carried out by Robert Elliot, assistant curator of its Canadian History Department. The funding also covered expenses for a travelling exhibition of a selection of the portraits.

Display large image of Figure 1

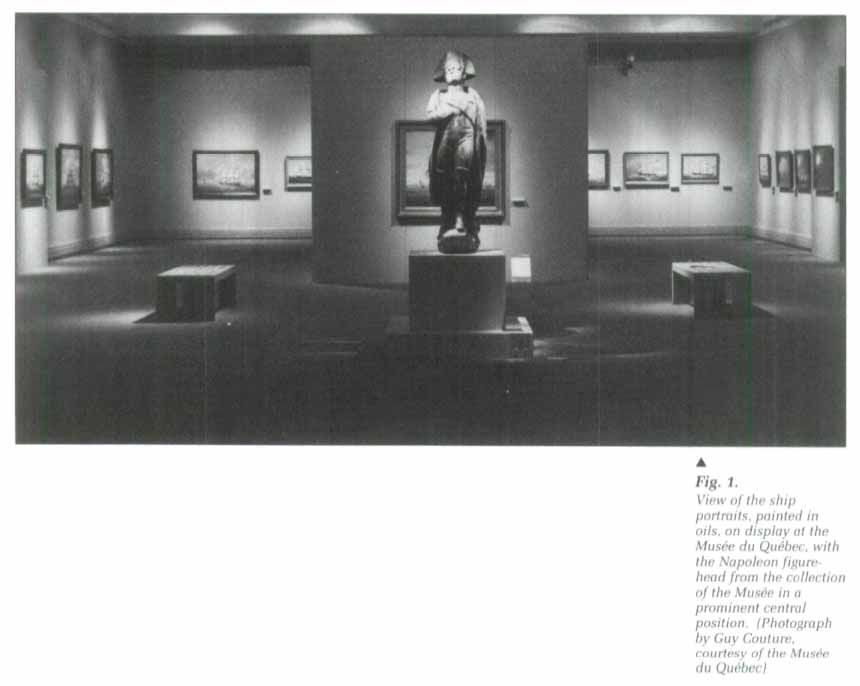

Display large image of Figure 13 The exhibition, prepared by Robert Elliot and Alan D. McNairn, art historian and director of the museum, was installed in ground floor gallery 2 at the Museé du Québec, where a large figurehead of Napoleon greeted the visitor (see fig. 1). The oils were hung around the gallery and on central panels, the watercolours and gouaches in the alcove. Both series were for the most part chronologically arranged according to the year of the vessel's construction, and together represent thirty-six sailing ships and one steamer, all of which were launched between 1825 and 1900. Twenty-seven of the vessels were of New Brunswick construction and in many cases belonged to New Brunswick shipowners. Of the ten others, two were built in Nova Scotia, one in Maine and one in Sweden, while six dating from 1881 on were vessels with metal hulls built in the British Isles. All ten were New Brunswick owned. In addition, a diagram on one of the rear central panels gives the names of the various parts of a sailing ship.

4 Sailing ship portraiture is a unique form of marine art, which had its heyday during the era of the sailing ship, mostly in the nineteenth century. Like other types of portraiture, faithfulness to the subject was the prime consideration. The prospective original owner was not looking for a first-class painting of some sailing vessel, however well it might be executed; he wanted a portrait of a particular one, with the hull, masts, ropes, sails and all other equipment correctly drawn. Moreover, he was a most discerning judge, and we can therefore assume that the majority of portraits met these criteria. Nevertheless, many of those in the exhibition besides being faithful portraits are also attractive paintings that elicit admiration from the viewer, duly evoking the "mystical love affair with sea and sail," which the catalogue tells us is the subject of the exhibition. But the catalogue also states: "the conventions of this type of painting were adhered to with such tenacity by so many artists that for the uninitiated who approach these works as they would more sophisticated 19th century painting the pictures look remarkably similar." Unfortunately, apart from a certain amount of relevant data on the individual labels, which, as we know, have a restricted readership, there is nothing to overcome this admitted limitation to the enjoyment of what must be a very large majority of the viewers.

5 Maritime historians or sailing ship enthusiasts, viewing the exhibition through informed eyes, will see it quite differently. They will delight in scanning each portrait, as a researcher scans a document, quickly picking out the significant variables. They will know the type of vessel from her rig and will soon realize the heavy preponderance of barques among them. They will note her name on a pennant at the mainmast, or perhaps on the bow, or on the stern of a stern view; they can identify the owner from the house-flag, flying from a mast, and will know that the Red Ensign at the stern signifies British registry.

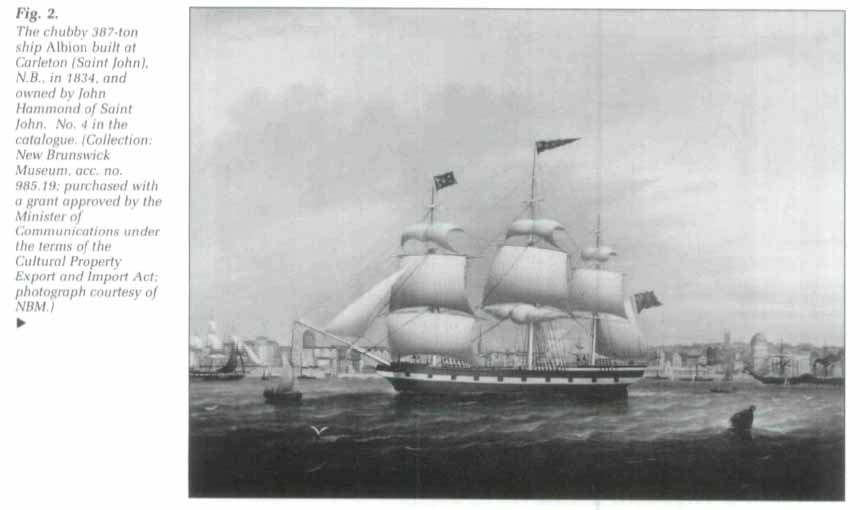

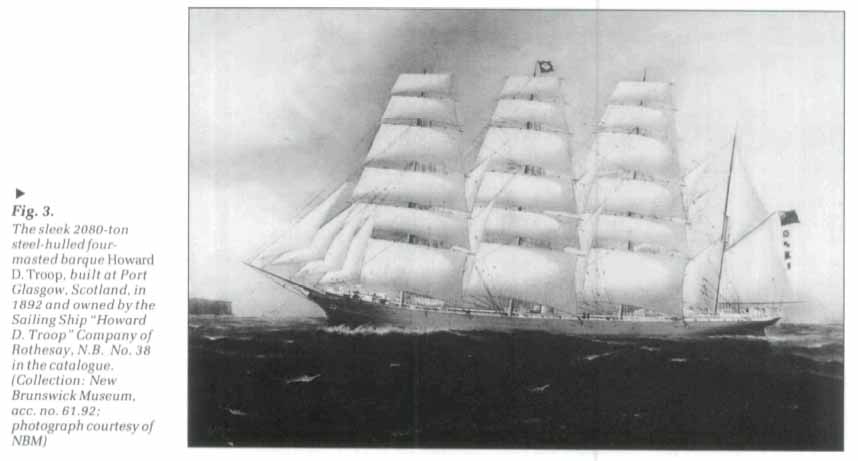

6 For this group, there will be much to indicate the period of her construction—the proportions of the hull, fullness of the bow, the curve of the cutwater gradually becoming quite concave, shape of the stern and much more. Compare, for instance, the relatively stubby apple-bowed and square-sterned 687-ton ship Albion of 1834 (fig. 2), a large ship at that time, with the long sleek 2080-ton four-masted steel barque Howard D. Troop with rounded stern of 1892 (fig. 3). The great care given to the correct representation of the sails and rigging will allow them to follow the general trends: the disappearance of studding sails after the mid-century, the huge single topsails giving way to double topsails on all the vessels portrayed that were built from 1862 on, and the double topgallants on the occasional vessel (e.g. the Robert S. Bethnard, the Centurion, and the Marathon) from 1872 on. Nor will the substitution of the spike bowsprit for the jib-boom on the British built ships of the 1880s and 1890s escape them. Happily, too, in the later paintings, the fact that the vessels are less likely to be shown on an even keel will enable the specialists to see the shape of the stern more clearly, as well as the deck arrangement of the increasing number and size of deck-houses. Unfortunately, the increase does not include shelter for the man at the wheel, who, it will be noticed, remains unhoused and at the mercy of the elements throughout. The deck-line and angle of the masts and bowsprit are details that the commissioner of the portrait would regard with a very critical eye, and these are among the many other details that will have meaning for specialists.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 37 The curators' aim is clearly stated in the catalogue as follows: "to encourage a broad audience to look at the visual evidence of the once thriving marine industries of New Brunswick and to consider these images as art and as evidence of historical facts." Certainly, they have succeeded in presenting the paintings as art to a broad audience and as historical records to the specialist. However, if all visitors are expected to consider them as "evidence of historical facts," then perhaps a few guides to help the general public "read" the evidence should have been provided. To set the mood, for instance, a display evocative of and making the connection between the portraits and the province of New Brunswick would have been more appropriate than the alien figurehead of Napoleon.

8 The curators are to be congratulated for the catalogue containing splendid colour photographs of the portraits exhibited with accompanying data, as well as a number of interesting black and white shots of shipbuilding that unfortunately are not included in the exhibition. The catalogue would benefit from an index, particularly since the generous size of the reproductions and the carefully researched data will make it one of the standard reference books of New Brunswick built and/or owned nineteenth-century ships, much appreciated by students of Canadian maritime history.

Curatorial Statement

9 Over the years numerous publications have examined marine painting in general and have given mention to the subcategory known as ship portraiture. However, far fewer books have treated ship portraits as a separate and distinct area of study. One of the earliest English-language publications to suggest that ship portraiture was a special subcategory within the genre of marine art was Oliver Warner's An Introduction to British Marine Painting (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1948). Nevertheless, a number of years passed before a writer devoted an entire publication (that was more than a picture book) exclusively to this subgenre. The majority of marine art publications, when they did include ship portraits, continued to lump these depictions and their painters with the works of more well-known marine and seascape artists—often making unfair comparisons.

10 Within the last twenty years, publications have appeared that consider ship portraits as documentary, as opposed to fine, art. This marked an important departure because these paintings of vessels were intended for a distinct clientele and were produced to perform an entirely different function from other types of marine art. Skibsportraetmalere by F. Holm-Petersen (Odense: Skandinavisk Bogforlag, 1967) followed this course, as did Werner Timm's Kapitansbilder Schiffsportrats seit 1782 (Bielefeld and Berlin: Verlag Delius Klasing, 1971) and Roger Finch's The Ship Painters (Lavenham: Terence Dalton Ltd., 1975). These authors and more recent investigators like Hanne Poulsen (Danske Skibsportraetmalere [Copenhagen: Palle Fogtdal, 1985]) of the Handels-og Sofartsmuseet pa Kronborg (the Danish Maritime Museum), have thoughtfully examined "what had once been regarded as merely naive, rather inferior and unimportant art" (Elliot and McNairn, Reflections of an Era/Reflets d'une époque. Foreword).

11 Despite the move towards a clear separation of ship portraits from marine art for serious examination and study, little has been attempted to verify the accuracy of these portrayals of specific merchant vessels. There are few satisfactory biographies of any of the artists and little detailed analysis of the ships as pictured in relation to surviving photographs, builders' plans and descriptions of vessels. Even though discrepancies have been noted, it is generally agreed that ship portraits are reasonably precise (David R. MacGregor, Merchant Sailing Ships 1850-1875: Heyday of Sail [London: Conway Maritime Press, 1984], p. 27). However, it has not been determined how accurately certain artists were able to depict their subjects. For a variety of reasons marine historians have been forced to assume that ship portraits were fairly truthful representations.

12 Understandably, this situation has arisen because comparative visual material is sparse for most surviving ship portraits, especially for the period prior to the widespread use of photography. This lack of visual evidence for authenticating individual paintings has created a problem; although ship portraits as a group are reasonably exact representations of various vessel types, it is difficult (and sometimes impossible) to determine the degree of accuracy represented in a specific painting. In fact, the research project undertaken by the New Brunswick Museum to produce "Reflections of an Era" was hindered by a lack of comparative material. Perhaps the only solution to this problem is to assess the documentary skills of individual artists and thus ascertain to what degree we can trust their works.

13 It was with these thoughts in mind that research commenced at the New Brunswick Museum in mid-1985 for the production of the national travelling exhibition "Reflections of an Era" and the catalogue of the same title. Following over twelve weeks of research at foreign institutions during that year, funded in part by a generous grant from the Museum Assistance Programmes of the National Museums of Canada, a representative selection of ship portraits of nineteenth-century New Brunswick merchant vessels was drawn from the collections of the Museum for more intensive study.

14 Despite the documentary limitations, a surprising amount of data can be extracted concerning both the environment of which the paintings were a product and the subjects which they were meant to portray. Of even more value when coupled with other sources of historical information, ship portraits provide twentieth-century landlubbers and marine historians with a pictorial record. Spanning the period from 1830 to 1900, the forty portraits in the exhibition and the 112-page catalogue document the evolution of merchant vessels constructed or owned by New Brunswickers and indicate trade contacts and voyages of a seafaring people. They represent survivals from an age when maritime enterprise shaped the lives of a people and was of critical importance to the economy of New Brunswick.

15 While the curators/authors do not claim to verify the level of documentary talent possessed by ship portraitists as a group (that remains to be done through studies of individual artists), it is hoped that our audience will appreciate the faithful illustrations produced by certain painters represented in the exhibition and catalogue. Nevertheless, it is abundantly clear that a ship portrait is much more than an artist's flight of fancy: ship portraits were intended to record visually the identifiable characteristics of a particular vessel and for this reason they are important and pleasing reflections of an era.