Reviews / Comptes rendus

Museum of the History of Medicine and the Mother-Child Project, Inc., "Mother and Child: History of Mothering from 1600 to the Present"

CURATOR: Felicity Nowell-Smith.

RESEARCHER: Linda Dale.

DESIGNER: Cameron Mustard.

TRAVELLING EXHIBITION: December 1986-September 1989.

Tour: Ontario Science Centre: Wellington County Museum: David M. Stewart Museum. Montreal: Mount St. Vincent Art Gallery. Halifax; Newfoundland Museum: National Exhibition Centre, Fredericton: National Museum of Natural Sciences; Milwaukee Public Museum: Vancouver Centennial Museum; Musée du Séminaire de Sherbrooke. Reviewed at Ontario Science Centre.

1 Every man, woman and child on earth is "born of woman." Furthermore, despite a dramatic decline in fertility rates in the past century, most women continue to bear at least one child during their lifetime. Yet in spite of the centrality of maternity in our lives, little is known about the changing conditions and experiences of motherhood. Portraying the history of mothering from 1600 to the present is the aim of "Mother and Child." Organized by the Museum of the History of Medicine (the Academy of Medicine) and the Mother and Child Project, this exhibit began a three-year North American tour with a five-month showing at the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto.

2 The exhibit is divided into two broad historical periods, 1600 to 1850 and 1850 to the present, the midpoint coinciding roughly with the beginnings of the industrial revolution. The first period opens with depictions of the dangers that childbirth held for both women and children. Amulets used by women in labour and their friends and family to ward off evil spirits are displayed, demonstrating the ways in which people sought to ensure a successful birth. Fertility rates in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were very high: a woman might have a dozen or more pregnancies, and she could expect to spend most of her life bearing and rearing children. As the exhibitors note, "[a] mother might have a child ready to leave home and marry at the same time she was suckling a newborn."

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 Birth was primarily a female experience. Women gave birth at home, attended by female friends and relatives and assisted by a local midwife. By the late eighteenth century, however, men had begun to take control of the birthing process. With the invention of forceps, male doctors were provided with a point of entry to the birthing chamber. By the mid-17008, male midwives used forceps and other obstetrical tools as standard equipment in childbirth. As the exhibitors note, this "new technology"—in use in Roman times and merely "re-invented" by Dr. Chamberlain— served as "an important part of a man's claim to superior techniques in midwifery."

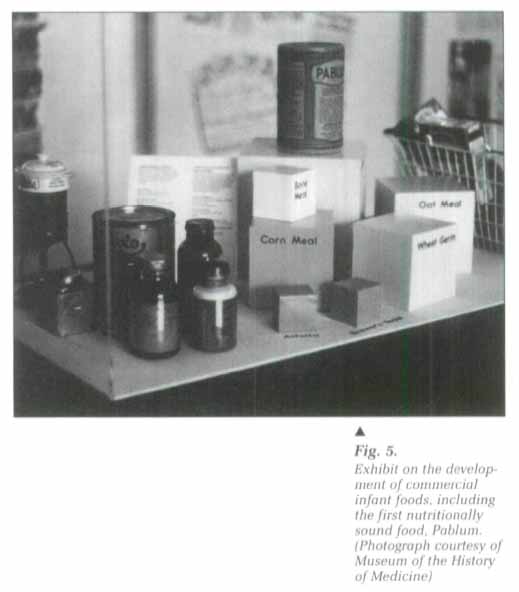

4 Male midwives faced considerable opposition in their bid to gain control of the birthing process. A caricature of William Smellie, a famous British male midwife, illustrates the resistance that often greeted these men. Smellie is depicted as half man, half woman: his male half holds the obstetrical instruments, his female half, the hearth and pap boat. Behind him are pictured shelves of love potions, labelled "For my own use." The accompanying text notes that "many men and women feared that the man-midwife would abuse his presence in the birth chamber."

5 Despite these fears, however, responsibility for the supervision of birth did gradually shift form women to men. Display cases contain obstetrical texts, showing the latest in "scientific knowledge." A small eighteenth-century ivory figure, on loan from the Welcome Museum of the History of Medicine in London, was used to instruct in the physiology of pregnancy. Increased knowledge of the processes of conception and pregnancy further solidified male hegemony over the birth process itself.

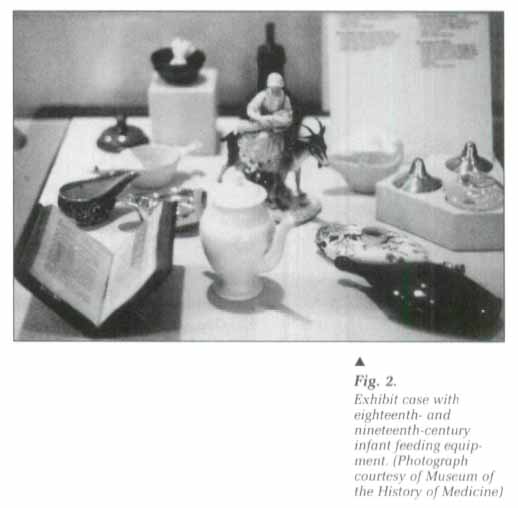

6 The technology of child rearing in the pre-industrial world differed dramatically from present-day methods. Drawings illustrate wet nursing, a practice that was widespread in an age when animal milk was mistrusted as fit food for babies. Infants were also fed pap— a mixture of flour, water and sweetener—and a variety of pap boats from the Drake Collection are displayed (fig. 2). Busy mothers swaddled their infants to keep them quiet and out of harm's way. Although this practice is viewed with alarm by twentieth-century theorists, the swaddled infant in fact bears a striking resemblance its Snugli cousin of the 1980s.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 27 The second period of the exhibit, 1850 to the present, contains more Canadian material and opens with a four-panel photograph of Montréal at the turn of the century, depicting the squalid living conditions of urban life. According to the exhibitors, Montréal in 1901 was "the most dangerous city in the western world for new born babies." One out of every three babies died before the age of one. Photographs from the James Collection (Toronto) and the Nortman Photographic Archives (Montréal) provide graphic representation of the poverty and disease that accompanied the transition to an urban, industrialized society.

8 In response to these conditions, a variety of reform elements initiated campaigns to "save the babies." The establishment of well-baby clinics, a programme to ensure a safe milk supply, and the institution of home visits by public health nurses were all designed to improve the health of the nation's children. The exhibitors note, however, that "while these reform programmes did have their benefits, they remained blind to the real problem— the extreme poverty and poor living conditions of the city's working class." Reformers relied heavily upon educational programmes designed to encourage the poor to "better" their lives. Mothers were taught the latest theories in "scientific childcare." Women were encouraged to remain at home with their children, rather than working for needed wages. For help, they were to rely on their doctors and on the flood of advice literature produced by the government and voluntary agencies in the years between the First and Second World Wars.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 39 Obstetrical practices also underwent dramatic changes as the scientific method transformed the process of birth itself. The invention of anaesthesia, blood transfusion, antiseptic procedures and, eventually, antibiotic drugs paved the way for the transition from home to hospital as the site of childbirth. Despite popular notions of the safety of hospital births, however, this shift was not without its attendant risks. The exhibitors note that "[m]aternal mortality rates in hospitals continued to be higher than those for home births until the 1930s," an assessment which concurs with recent work by feminist historians. Home remained the place of birthing for most Canadian women until the mid-1930s. A birth mat made of newspapers covered with cheesecloth demonstrates one method used to protect the birthing bed. On loan from the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, it exists only because it was never used.

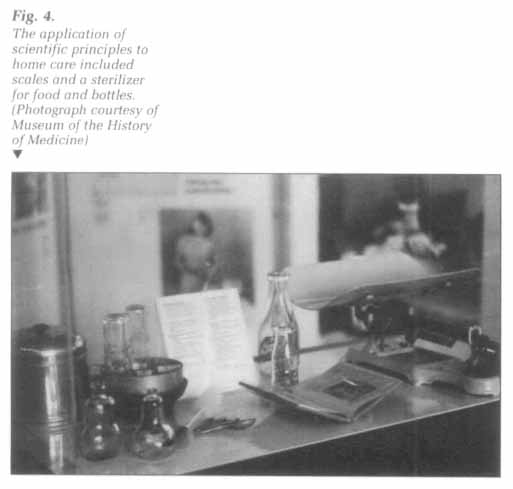

Display large image of Figure 4

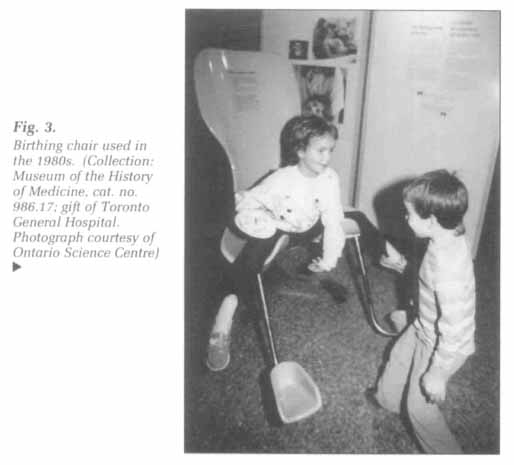

Display large image of Figure 410 By the 1950s, a hospital birth was considered to be standard practice. A suitcase with nightie, powder and a copy of Dr. Spock, and a pair of birthing stirrups illustrate the modern experience of birth. These are juxtaposed with two quotations form a 1957 Ladies' Home Journal article documenting readers' experiences of hospital birth. The exhibitors question the impact that changing technology may have had on women's lives, noting that "while women no longer feared for their safety during birthing, they had lost a sense of control and the feeling of warmth which had been an important part of home birth." Photographs in the final section of the exhibit, showing women in the 1980s with a midwife and a male coach, illustrate the recent trend towards reclaiming the birth experience. The only artifact in the exhibit that invites viewer participation, a birthing chair in use in Toronto General Hospital in the early 1980s (fig. 3), illustrates the way hospital technology has begun to adjust to the demands of women.

11 The final section of the exhibit is devoted to twentieth-century child care. Cleanliness. rigid discipline and scheduling became the watchwords of scientific child rearing. Artifacts, including an enormous box of Pablum (which was invented by Doctors Drake and Tisdale of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto), baby scales and the paraphernalia required for sterilizing baby bottles, illustrate the dramatic changes in the technology of infant care and feeding in this century (figs. 4 and 5). Advertisements with scientific claims came to dominate the marketplace, as products ranging from Kleenex to baby foods employed images of doctors and nurses in their promotional literature. A photograph of an enormous stack of current child-rearing books demonstrates the key role that expert advice literature has come to play in the lives of modern mothers.

12 The "Mother and Child Exhibit" is very successful in depicting the changing technology of childbirth and child rearing during the past three hundred years. Geared towards a general audience, the displays are attractive and informative. Labels are concise and clear, providing both the source and the context of the photographs and artifacts on display, with the exception of an exhibit of sponges in the section on domestic medicine.

13 On the three occasions I visited the Ontario Science Centre, the exhibit was well attended. Small children, babies in strollers and entire families were very much in evidence, and people lingered over the items, reading the text and commenting to each other. The exhibit space and adjacent area seemed to be attractive to families, in keeping with the Centre's mandate and orientation (see fig. 6).

14 The exhibit serves to challenge many popularly held notions about motherhood. In contrast to the unchanging image of motherhood projected in the media and elsewhere, the exhibitors insist that "Mothering has a history. As society has changed, so have the rituals of childbirth and the ways in which women care for their children." The exhibitors adopt a critical stance towards the transition to a "safe, sane and scientific" motherhood, noting the actual physical dangers associated with hospital births in the first third of this century, and the loss of control and comfort women experienced with the increasing use of technology in childbirth. In this age of science, the presentation of such a critical viewpoint is a welcome change from the "progress marches on" image of popular media. Furthermore, in light of the current struggles over home birth and the role of midwives in birthing, the exhibit serves to provide viewers with a historical context for these debates.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 515 My main criticism concerns the physical set-up of the display. Unfortunately, the exhibit is difficult to negotiate. There is little clear indication of where to begin, and once in the middle, the visitor is often faced with several options with no indication as to how to proceed. The placement of the section on Victorian child care at the end of the exhibit leaves one wondering whether a turn has been missed. These difficulties may in part be blamed on the space allotted to the exhibit. They could, perhaps, be overcome by the addition of a written guide describing the exhibit and providing direction for the visitor. Failing this, numbering the displays might help.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 616 Although I am impressed with the breadth of the subject matter tackled by the exhibition planners, I should like to comment on three gaps in its coverage. The first, and most glaring, is the complete absence of any reference to birth control or abortion. While this subject might merit an entire exhibit in itself, I would maintain that the avoidance of pregnancy represents a significant aspect of the experience of motherhood and should warrant some discussion and display, however brief. The exhibitors also fail to mention the dramatic decline in fertility that began in the late nineteenth century. This decline, perhaps as much as the changing technology of childbirth and infant care, served to transform the experience of motherhood in the twentieth century.

17 Any exhibit is, of course, limited by the availability of resources. In this case, the exhibitors have relied heavily upon the T.G.H. Drake collection of artifacts and printed materials. Although Dr. Drake lived and worked in Toronto, his collection, which includes some nine thousand items, contains primarily European materials. Thus, for the earlier period in particular, the exhibit is heavily European in focus. This means, unfortunately, that little is included on the experience of pioneer or native women. The latter group had their own traditions of birth which came into sharp conflict with the practices of Western medicine. The destruction of native traditions and rituals, the enforced separation of families, the experimentation upon native women, are facts that are all too often ignored in books and exhibits depicting the "Western" experience.

18 "Mother and Child" is, nonetheless, an extremely interesting and well-mounted exhibit. The exhibitors have succeeded in drawing upon recent scholarship in the history of medicine and presenting it in an accessible, entertaining and highly informative manner. In this age of "designer" babies and the latest in baby technology, the exhibit provides us with a much-needed historical perspective on the experience of motherhood.