Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

The McWilliam House Hallway:

A Painted Room in Drayton, Ontario

1 In 1980, Hank and Alice Reinders bought a two-part house on Main Street, one of the major crossroads in Drayton, located in Ontario's Wellington County. The house had been built soon after 1885 as a residence and office by Dr. Robert McWilliam, when he set up his medical practice as the third doctor in Drayton. The Reinders moved into one of the two portions of the house, and in early 1984 began to prepare the second portion for re-decoration. While scraping away the wallpaper in the large first-storey entrance hall, they made a discovery.1

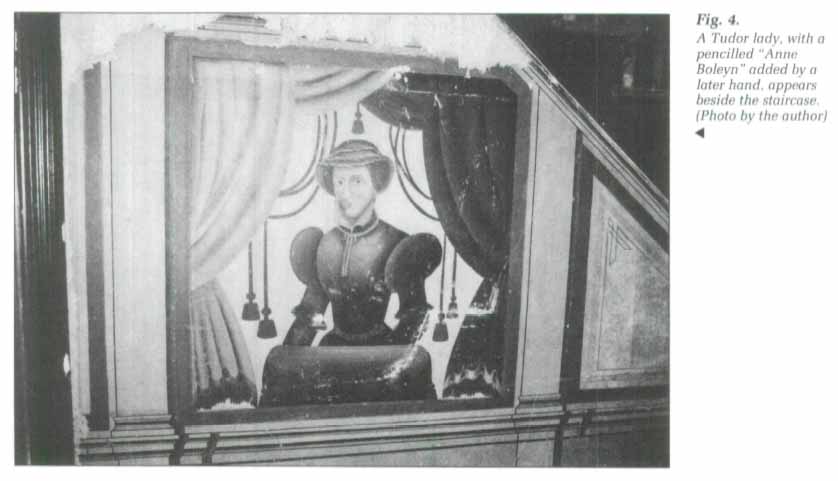

2 The walls beneath the paper had been extensively painted with architectural elements, decorative motifs and—most surprisingly— portrait busts of prominent people, mostly from the nineteenth century.2 Pencil notes were found on many of the images, as if a paperer, after filling in cracks and hence partially obliterating the paintings, had wished to document what was about to disappear. The names inscribed are "John A. Macdonald," "George Brown," "Prince Albert," "Queen Victoria," "Oliver Mowat," "Edward VII" and, anachronistically, "Anne Boleyn." A small image next to the front wall appears to depict the poet Robert Burns. If this image bespeaks a Scottish heritage, the Tudor lady labelled "Anne Boleyn" may actually represent Mary Queen of Scots, whose portraits the image resembles.

3 The use of the title "Edward VII" confirms that the pencilled labels were not contemporary with the paintings, for that monarch reigned 1901-1910. He was Prince of Wales when the paintings were most likely executed, for they appear to have been painted directly on freshly dried plaster, probably when that part of the house was built in the late 1880s.

4 The date the paintings were first covered with wallpaper is more difficult to establish, but there are some clues. Dr. McWilliam sold the house to Dr. James Cassidy in 1908 and moved to Gait (now Cambridge), Ontario, where he died the following year. Dr. Cassidy's name was reportedly found written on a portion of a doorframe that had been placed over wallpaper, perhaps during the process of enlarging the house. Since Cassidy sold the house in 1913, the first layer of wallpaper may have been applied over the paintings during his five-year occupancy.

5 In any event, the hall's original appearance was never quite forgotten. Mrs. Viola Noecker and Mrs. Edna Brandon, later twentieth-century occupants of the house, recalled an episode when, during repapering, the paintings were briefly revealed. This event probably occurred when Frank Brandon purchased the house in 1941. A number of visitors arrived to view the sight, but "there wasn't the interest then in this heritage stuff." And indeed, the authors of A History of the Village of Drayton (1957) did not record the presence of the hidden paintings.3 Matters had changed when Drayton's Historic Album (1975) stated of Dr. McWilliam that "his wife had painted beautiful pictures in the west half of the double house which are now covered with wallpaper."4 An examination of the paintings may throw light on the question of whether this attribution is correct.

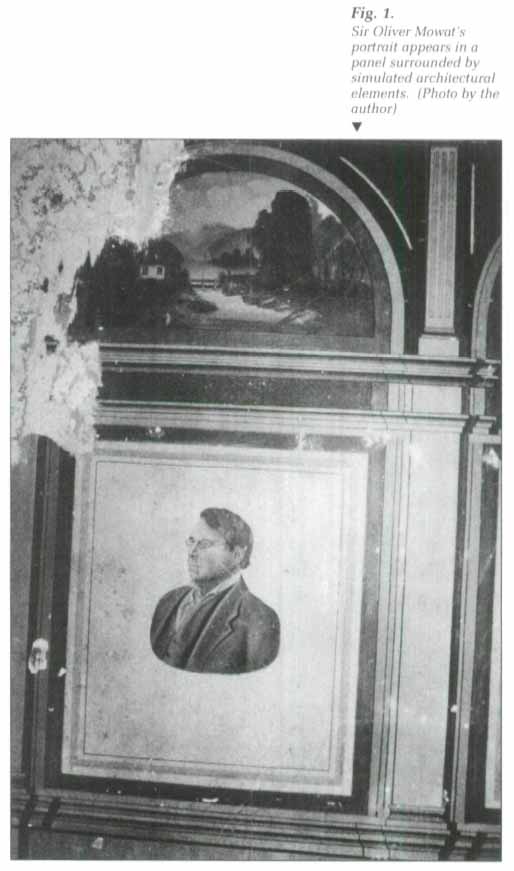

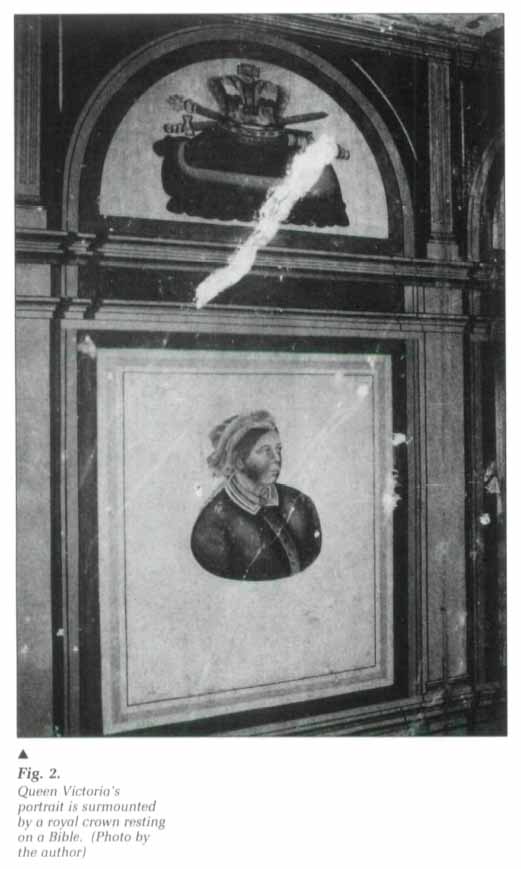

6 The portraits of Queen Victoria and her consort depict the royal pair in middle life, perhaps as they appeared not long before Prince Albert's untimely death in 1861. The visages of Brown, Mowat and Macdonald closely resemble contemporary photographs, reproducing pose and costume as exactly as the painter's skill permitted. George Brown first published The Globe (later the Globe and Mail) in 1844 and entered the Ontario Provincial Assembly in 1851 as an independent Reform candidate. Later in the nineteenth century he was involved in the "reform" of the Liberal party. Sir Oliver Mowat was a Liberal too, and Premier of Ontario 1872-1892, serving as Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario 1897-1903. Sir John A. Macdonald, a Conservative, was Prime Minister 1867-1883 and 1878-1891. The careers of these personages cluster around the period when the paintings were executed. Victoria was on the throne, her son was Prince of Wales, and both Mowat and Macdonald were in high office. As Michael Bird has remarked, it is "no ordinary meeting of personalities."5

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 37 In addition to these eight portraits, there are nine arcade panels with landscapes, groups of figures and symbolic motifs, as well as two other distinctive images placed above a feigned bannister. The latter include a representation of the pair of putti who gaze from beneath the feet of Raphael's Sistine Madonna and who peer here over the motto "Home Sweet Home" at visitors approaching the foot of the staircase leading to the second storey. Below them is an extravagant floriate motif consisting of urn flanked by confronted griffins.

8 The simulated architectural elements consist of a base and dado which form a stylobate for a series of bold pilasters dividing the central wall region into panels, punctuated by several doors. These vertical divisions continue through an entablature of architrave, stencilled frieze and cornice, to an arcade, the spandrels of which contain smaller pilasters adorned by reeded fluting (fig. 1). The dado is blue; the panels are white, framed by olive borders and narrow bands of red and blue; the frieze and spandrels are red stencilled on olive; and all the simulated structural elements are cream and light grey. The ceiling, originally white, sported a stencilled border in brown, red, gold and blue.

9 Because most of the portraits were taken from photographs, they vary in their sartorial complexity. Victoria wears a white-collared black dress and white headdress, adorned with earrings and a colourful pendant containing a red cross (fig. 2). Albert's head is uncovered, but although he appears grim-faced and weary, he wears a handsome blue uniform with silver epaulettes, a red collar and the military version of the Order of the Garter. Although draped in red and blue curtains with gilded and betasselled ropes, the Prince of Wales, like the rest of the male figures, wears a black suit and white shirt with dark tie. Only Robert Burns, true to his own period, wears a blue jacket with yellow lapels (fig. 3). Red and blue curtains also enhance the portrait of the red-haired lady in Tudor garb. She wears a black dress, a white cap, a red and blue belt, earrings and a pearl necklace with a gold cross, and gazes at us, visible from the waist up, across a large pillow draped in a black cloth (fig. 4).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 410 There are three styles or manners of painting here, the relationship between them posing a puzzle. Unlike wall paintings, which open a room by creating an illusion of distance and vista, these firmly structure the interior with illusionary architecture. The technique is that of the limner or artisan decorator, like those of Nova Scotia described by Cora Green-away.6The delineation of these spaces is formal and expert, the work of the trained practitioner who also stencilled the ceiling. The task is so well accomplished that the artificial elements appear appropriate and convincing.

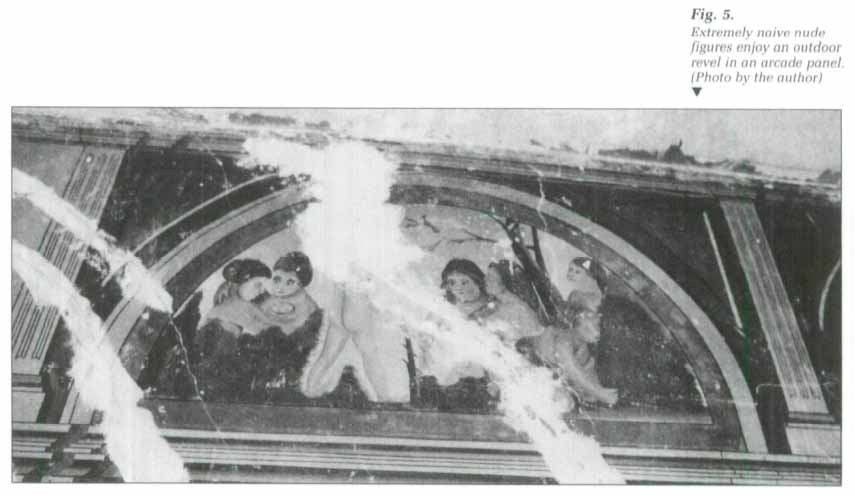

11 The second style is that of the panels in the arcade and the two motifs above the stairs. Some contain idyllic landscapes, conventionalized and coarsely painted. Others, likely from the same hand, show nude revellers, in some naive Arcadia or infantile Olympus (fig. 5). Like the landscape components, these figures are flat and crudely executed: memories of memories, not drawn from any immediate source but from the idea of representation, emptied of literal meaning and reduced to ornament.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 512 But the other arcaded panels present lively assemblages of symbolic artifacts, emblemata of royalty, government and human relationships. Two doves with a billet-doux, or lover's note, fly before a bough from which hangs a pair of Cupid's arrows; a handsome lute is surrounded by floriate tendrils; the royal arms are enclosed with garter and motto, supported by lion and (when complete) unicorn; the royal crown, sword and sceptre rest upon a "Holy Bible" borne by a pillow. These, like the putti, are vigorous and expressive. The whole ornamental scheme combines formality, naivety and exuberance, while remaining chastely flat upon the walls, an eclectic mélange of nineteenth-century adornment most likely painted by the hand of some provincial artisan.

13 If this were all, we would be charmed, but not amazed. In fact, the entire decorative system is scarcely noticed by the viewer who enters this vestibular world, because of the emphatically didactic programme of portraits, so distinct and demanding of attention as to suggest an individual mind. Floating boldly in the centre of the rectangular panels, and shoehorned into additional spaces under the staircase and close to the front wall, these images declare allegiance, attest to loyalty, signal partisanship and even ethnicity. The forceful didacticism of these precisely selected images contrasts with the fanciful eclecticism of the framing environment.

14 As the paintings, and by implication, the iconographic programme, are attributed by local tradition to Josephine McWilliam, certain surviving memories of her activities are of interest. She is reported to have taught art classes attended by a number of young ladies of the community. Several charming landscapes in a private collection are attributed to one of her students, Susan Norris (b. 1885), by Mr. and Mrs. Russell Day of Goldstone, Ontario. A small black and white oil on cardboard, The First Lesson, also in a private collection, is attributed to "Mrs. Dr. Mac" herself; in this work, three puppies stare apprehensively at a rat their mother has killed. This work was given as a wedding gift to Josephine McWilliam's employee, Rachel Case, about 1900. While the style and to some extent the brushwork of these efforts is clearly derived from the same period as the wall paintings, they do not appear to be from the hand of the "McWilliam House Painter." Josephine McWilliam was, for her time and station, probably considered a better "artist" than the artisan she and her husband presumably hired to decorate their handsome hallway. The academic manner she used and taught was more refined as well as less forceful than the works on the walls of her hallway.

15 The grandiose conception of the entrance hall accords with a style of decoration that, although close to its demise, was still in full flower in the 1880s. It seems likely that these painted walls met with the approval and fulfilled the wishes not only of the artistic Josephine McWilliam but of her husband. Fortunately, a sketch of Robert McWilliam's public personality is also available. The Drayton Public Library has preserved a scrap-book of clippings from the Drayton Public Advocate (circa 1941) which includes a column called "Dipping into the Past," described as "Gleanings from the Advocates of Other Days." These selections include incidents from the 1880s and 1890s that show Dr. McWilliam as a colourful local figure. For 1889, a list of names, including "Dr. Robert McWilliam, Physician," is preceded by the remark: "The following list of Drayton business men and women is of historical interest and well worth preserving." For 1894, Dr. McWilliam is listed as chairman at a local Reform meeting. For the following year, 1895, it is noted that "Jno. Edmison, Rothsay, medical student, came to work with Dr. McWilliam for the summer." For 1896, it is observed that "A familiar sight in Drayton in the last decade of the Nineties was Colonist, Dr. McWilliam's fine race horse. On Dominion Day Colonist won top honours at the Mount Forest races." Finally, for 1900, the "Gleanings" remarks that "We notice such winners as Dr. McWilliam . . . let the contract to R. Downey and Son for a new place of business."

16 A man of affairs, a doctor to whom students repair for internship, the owner of a "fine race horse," a "winner": this is the Dr. McWilliam whose reception hall displayed the portraits of major royal and political personages of his day. The answer to the question "Who painted these works?" may be beyond the reach of human memory, but we can grope toward it by means of a second question, "Why were these images painted?"

17 Perhaps the political portraits were suggested by Robert McWilliam, whose engagé lifestyle included a high public profile, an interest in Reform and even a touch of ostentation as his prize-winning racehorse appeared frequently in town. And it may be that Josephine McWilliam, an artistic woman who was ready to educate the daughters of her community, hoped that the elegant simulated architecture and elaborate symbolic motifs would suggest a great house in Britain or a grand home in Toronto.

18 In a useful terminology suggested by Michael Bird, folk art can be divided into two fundamental categories: "ethnosyncratic," art based upon and expressive of community style and values; and "idiosyncratic," art derived from the individual personality.7 Art in the second category is often didactic, directed toward embodying concepts which, while shared to a degree with the general culture, have been given a special twist or spin by the mind of the individual. The portraits of political figures displayed in the McWilliam entrance hall exhibit this didactic and idiosyncratic tendency. These explicit icons are, however, accompanied by images of a more general, culturally determined nature.8 As ethnosyncratic works of the late nineteenth century, they attempt to meet certain expectations, to draw assent or approval from a certain audience. Based upon elevated prototypes, the architectural framework and its adornment are derived from ubane sources, albeit expressed with a provincial exuberance, even a naive charm. Indeed, the failure to achieve a perfect imitation of the emulated prototypes in both ornament and portraiture has produced a style that today, a century later, makes these paintings seem not only delightful but significant.