Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Artifact Survivals from Pre-Loyalist English-speaking Settlers of New Brunswick

1 One era in New Brunswick's early history that has received little research attention is the period between the expulsion of the Acadians and the influx of refugee Loyalists, roughly from the late 1750s to 1783. These years were marked by the arrival in the region of more than four thousand settlers from New England and the British Isles, mainly Massachusetts and Yorkshire, respectively, with some Scots, Irish and a few Germans. The Loyalists sometimes referred to these people as the "Early Comers."

2 In an attempt to remedy this neglect, the New Brunswick Museum has launched a search for artifacts that have survived from this intermediate period and is preparing an inventory of objects made or used by these English-speaking colonists for publication in a forthcoming catalogue. Designed for the use of researchers and informed amateurs, this illustrated catalogue will present the history and function of each artifact, with a preliminary essay on how each fits into the society of the times.

3 Despite the comparative lack of scholarly attention, this was a colourful and significant period. These settlers—"Planters" was the contemporary term—faced not only the usual hardships of pioneers, but the dangers of Indian raids and, as the smouldering fires of American discontent burst into the flames of the American Revolutionary War, arson and pillage by roving bands of soldiers and plunder by New England privateers. It was the Planters who determined whether the region would stay with Britain or join the Thirteen Colonies in revolt and who continued to have considerable influence on political events, siding with democratic and against autocratic forces.

4 The importance of taking immediate action to find surviving artifacts of this period is obvious. Many have already vanished beyond recall, and there are numerous instances where articles that once belonged to these people were in place a short time ago, but are now irretrievable. One case in point is that of a chair used at one time by John Wesley, the founder of Methodism. This chair, with other furniture of the period, was owned until recently by an elderly lady whose possessions were dispersed in unknown directions upon her death.

5 For various reasons the pre-Loyalist British artifacts that have survived are far from numerous. Many have been collected and removed from New Brunswick by antique dealers from the United States and Ontario. Others were discarded by their owners as worn out or out-of-date. In any case the settlers who came from New England do not seem to have brought large amounts of rich goods with them; they were attracted to this region by the land grants offered in 1758 when Governor Lawrence appealed for English-speaking settlers to occupy the lands from which the Acadians had been removed. The later, prosperous Yorkshire group, who mostly purchased their lands, would seem to have brought more material wealth.

6 The key concern is the authentication of any surviving artifacts. For every ten objects that have surfaced to date, ranging through such items as clocks, desks, chairs, tables, paintings, maps and china, eight or nine must be eliminated because their provenance cannot be established. They may be of the pre-Loyalist period, but may have arrived later with a Loyalist settler; others are later reproductions of early styles, or have come into the province from outside, and thus shed no light on New Brunswick's "Early Comers" and the way they lived. Sometimes, however, the pedigree can be established through successive wills or contemporary inventories that describe the artifacts in detail.

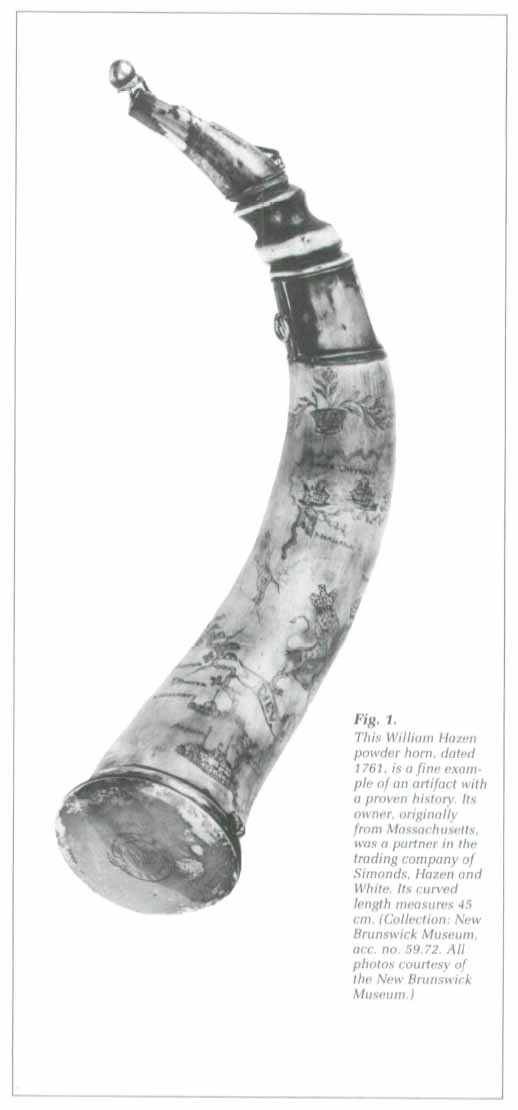

7 A fine example of such an authenticated artifact, now in the collections of the New Brunswick Museum, comes from one of the families of the firm of Simonds, Hazen and White. Their trading post, established in 1762 at Portland Point at the mouth of the Saint John River, played a major role in supplying the up-river settlers, and in other events of the time such as the establishment of Fort Howe. The powder horn (fig. 1) that young William Hazen (he spelt it "Hazzen") used in the Seven Years' War is inscribed with his name and a map of the route from Albany to Montréal. A Hazen descendant later replaced the original wood fittings with handsome silver mountings bearing a crest. The horn was a bequest to the Museum from the family.

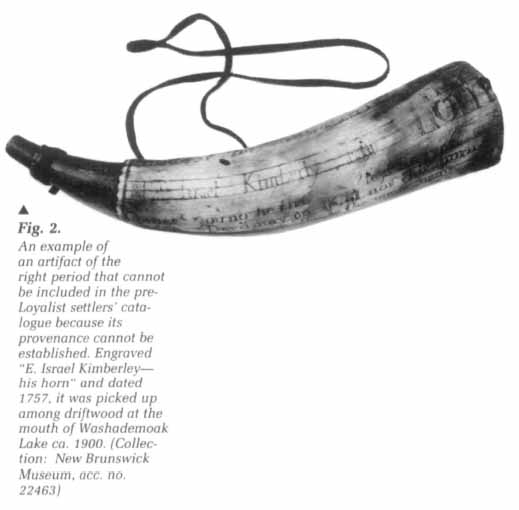

8 By contrast, another powder horn (fig. 2), also among the Museum's collections, cannot be authenticated. It is datable and of the right period, but was found among flotsam on the shores of Washademoak Lake. It may have arrived in New Brunswick with a disbanded soldier, one of the early settlers, or a later Loyalist, or been acquired outside the province by a collector.

9 Among some of the other artifacts that have come to light are several clocks with a continuous history dating from the early 1770s. Only the works, which include ornate brass faces, arrived here with Yorkshire settlers; the tall wood cases were made locally in New Brunswick. On the clock faces are the makers' names and the places of manufacture in England, integrated into the balanced and elegantly inscribed designs featuring birds in flight (perhaps a reference to the flight of time?) and floral motifs. These clocks are still with the original families.

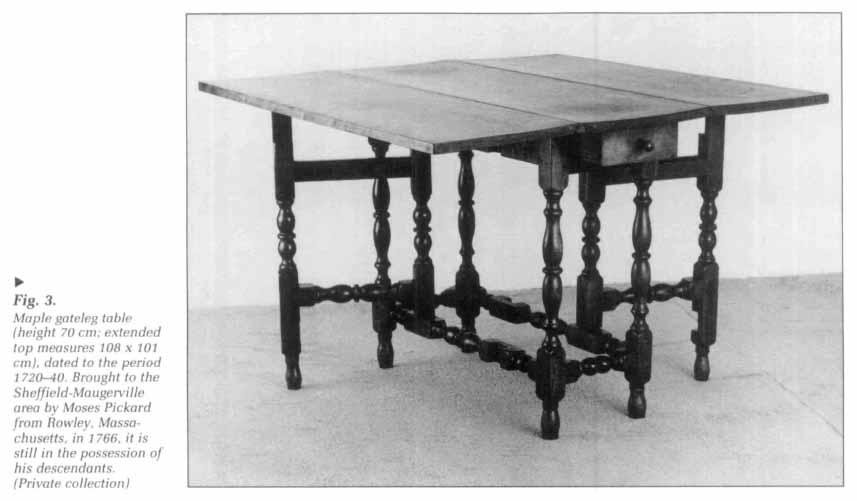

10 Other authenticated items include a maple gateleg table (fig. 3) and a fine slope-front desk of curly birch. There is even an entire farmhouse, dating from the mid-1770s and built of brick manufactured from the mud of the Tantramar marshes. The working farm— still in the hands of descendants of the original Yorkshire immigrant, William Chapman— straddles the border of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and the house site is on the Nova Scotia side.

11 As research progresses the Museum is consulting experts in many fields according to the type of artifact, materials used, etc. This is proving to be a most complicated project, and suggestions for further research arc invited, and information on any known artifacts and on methods for authentication is welcomed.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 312 Underlining the significance of the period, Acadia University has organized a conference on Planter history and culture, to take place in late October 1987. The New Brunswick Museum will report on research to date under the title of "New Brunswick's 'Early Comers': Lifestyles through Authenticated Artifacts; A Research Project."