Articles

Beyond Brown Bread and Oatmeal Cookies:

New Directions for Historic Kitchens

Abstract

This paper examines the operation of historic kitchens from a museological point of view. Four major research questions are posed: What is the view of history and the nature of the museum experience presented by this kind of historic site museum? What are the limitations of present programming at these sites? What kinds of research are valuable for domestic living history? What are the most profitable directions for future work in this field? The central problems with the presentation of history and historical food are a lack of in-depth research and a tendency to homogenize the past. By examining the museological implications of historic kitchens, it becomes apparent that there is an obligation for them to research processes as well as artifacts, and to broaden the scope of their research.

Experimental archaeology is a discipline that should underlie the research activities of historic kitchens. By applying the techniques of experimental archaeology, historic kitchens can increase the amount and quality of their research and move beyond their traditional interpretive activities.

Résumé

L'article considère les cuisines-musées d'un point de vue muséologique et pose quatre grandes questions : quelle est la valeur historique et muséologique de ce genre de musée, quelles sont les limites des programmes actuels dans ces musées, quelles sont les re-cherches importantes pour comprendre la vie domestique d'autrefois, et quelles sont les voies que les chercheurs auraient avantage à explorer? À l'heure actuelle, cette vulgarisation de l'histoire et de l'alimentation de nos ancêtres pèche surtout par un manque de recherche approfondie et une tendance à l'homogénéisation. En examinant l'aspect muséologique des cuisines historiques, il devient évident que les chercheurs doivent documenter les usages au même titre que les objets, et qu'il y a lieu en général d'élargir la portée des recherches.

L'archéologie expérimentale devrait sous-tendre la recherche concernant les cuisines historiques. En effet, les techniques de cette discipline peuvent permettre aux responsables des cuisines-musées d'augmenter la quantité et la qualité de leurs recherches et de présenter une information plus solide que jusqu'à maintenant.

1 Every day, at any number of historic sites and restored environments in Canada fires are lit, stoves and ovens are heated up and "historical" food is prepared and served by costumed interpreters to museum visitors. The historic kitchen is a hallowed North American museum institution and ever-popular with visitors.

2 The historic-house movement has a long history in North America, as do the kitchens within the houses.1 Images of smiling older women in bonnets or mobcaps cordially offering up a plate of freshly baked oatmeal cookies and inviting visitors to "step back in history" grace the covers of countless museum and historic-house brochures.

3 Often, the visitor's experiences at widely differing sites can be disconcertingly similar. For example, one could be forgiven for imagining, after spending a day visiting such museums, that the residents of Ontario before 1900 lived exclusively on cookies. Have all of these sites independently reached the same conclusions through rigorous research, or are the same few treasured facts and recipes making the rounds from kitchen to kitchen?

4 This apparent homogenization of history may be a reflection of the enduring popularity of "pioneer times," that splendidly elastic historical period which seems to encompass any date earlier than 1900. The large number of sites with the word pioneer in their names attests to the powerful draw such a term has for the public.

5 If a historic kitchen or restored environment is truly a museum, then a large body of museum theory suggests that it is supported by such museological activities as research, collection, conservation and interpretation. Is the research process by which a restored domestic environment operates clearly defined in either its difference from or similarity to other kinds of museums? Has the process by which historical fact becomes interpretive programming been examined?

The Oatmeal Cookie Syndrome

6 In looking for examples of this research process, it appears that many historic kitchens in Canada are run not on an organized research plan but rather by a fortuitous combination of the common sense of the cooking staff and a few of grandmother's recipes, the sources of which have been forgotten or were never recorded.

7 While this type of presentation may satisfy visitors, it obscures the fact that the historic kitchen is really one of the most complex areas of the living-history field. Its operation may appear simple because often interpreters need not interpret anything at all: the visitor simply steps through the door of the kitchen and begins to reminisce aloud about the cooking or the baking of a departed relative. The evocative power of freshly baked bread, old stoves and old wooden tables must be seen first hand to be appreciated. Very little is required from an interpreter to fill out the visitor's experience. The simple dispensation of an oatmeal cookie completes the transaction, and the visitor exits, having had a "taste of history." In a historic kitchen, the visitor feels comfortable. As Mary Lynn Stevens points out,

8 Despite the best efforts of museum designers, programmers and interpreters, visitors will take away what they please from the experience of their visit. There is in fact nothing wrong with a primarily emotional experience in a historic kitchen. Indeed, many interpreters work in that environment because they genuinely love it, relishing the sounds, smells, tastes and sensations that they encounter there. They are able to have an emotional experience and still present good historical information. The question to be asked, as Stevens says later in her article, is "How well nostalgia works. Might other approaches be more useful or work better?"

9 The initiative to do more must come from within the institution; in addition visitors should be urged to pose questions. The incentive to change might eventually come from both visitors and site staff. Thomas Schlereth touches on the potential education has for making a museum visit more rewarding:

10 Domestic historical interpretation, if it is to fulfill its potential for providing a complete multisensory museum experience to visitors, must move beyond the immediately gratifying activities it has traditionally supported, such as handing out cookie samples, and into new areas. For instance, a historic kitchen can serve a debunking function by using the sense of taste to correct naive perceptions of history, the past or "bygone days."

11 A period recipe is a set of directions for the reproduction of an ephemeral artifact, and its every performance is an act of experimental or replicative archaeology. The number of factors that influence the production of accurate historical food in a historic kitchen is remarkable. Ingredients, pots, pans, ovens, hearths, the recipe and the interpreter's skill can all have a great effect on the accuracy of the results. Because of this, a historic kitchen is not so much a place for theatrically evoking memories as it is a dynamic research centre for conducting investigations into historical foodways.

12 Three new rallying cries for historic kitchens are offered:

- Interpreters in historic kitchens must cook, cook well, and cook often. (As Peter Cook shows these activities must be founded on genuine skill if they are to be interpretively valid.4

- Historical food can taste good and still be good history.

- One pudding is worth (at least) ten tours. The actual taste, texture and appearance of the food, when coupled with an articulate and sensitive interpretive commentary, make an extremely effective statement to the visitor.

13 In a historic kitchen that does not pass on treasured memories but disseminates critical and accurate information about historical food and cooking, the interpretation performed for visitors comes directly out of research. The visitors see the staff working in what is essentially a historical laboratory, and indeed, one of the advantages of living history is that newly discovered information can be conveyed directly to the public. If interpreters are the ones who conduct the primary source research, they will be that much better equipped to engage visitors in a dialogue about what they are doing, instead of what "they would have done back then."

14 The visitor's experience does not end in the kitchen itself. The kind of information given out in historic kitchens—the facts, recipes and ideas that the visitor takes away—is as important as the immediate transaction between interpreter, visitor and food sample, if not more so. Many unconventional methods can be used. For instance, a historic kitchen can establish a link with modern food writers and editors and publish recipes or articles in popular magazines. Even here, however, the inherently sentimental and emotional connotations of food and eating can overwhelm common sense and accurate research, if the publications relating to historical recipes and cooking are any example. Roy Abrahamson, for instance, in his preface to the republished 1831 edition of The Cook Not Mad, goes so far as to say,

15 The Cook Not Mad, an important early Canadian imprint and valid example of an early nineteenth-century cookbook, is here treated simply as a curiosity. The misguided sentimentality of Abrahamson's introduction is indicative of an attitude towards history that has no place in a museum or historic site purporting to do research. With research and experimentation in a historic kitchen, The Cook Not Mad could indeed become a "how-to" cookbook; nevertheless, it remains, as it has always been, a real cookbook, not some kind of quaint historical tract.

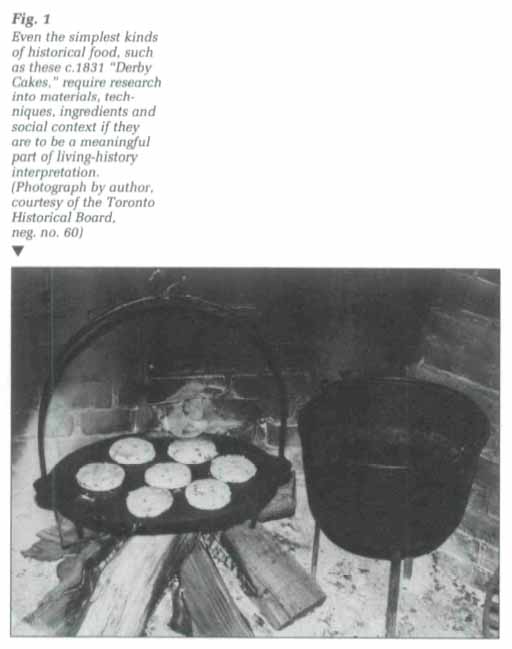

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 116 In addition, a further examination of The Cook Not Mad reveals an insidious trap common to republished cookbooks, that is, the so-called "modernization" of recipes. Historical recipes are often not so much modernized as bowdlerlized. While they may produce perfectly good food in their new form, they generally will have lost any pretence to historical accuracy.

17 The development of modern equivalents for historical recipes is a complicated process which must balance accuracy with palatability and scrupulously report any alterations made to the original recipe. The editors of The Cook Not Mad did not trouble themselves with such subtleties, as can be seen in a "modernized" recipe for preparing fish that now calls for MSG.6 In this case, the historical recipe has disappeared in the modernization. A better term than "modernized" for well-researched recipes might be "equivalent," since this more accurately conveys the relationship between past and present.

18 The distortions and misrepresentations seen in The Cook Not Mad are also present in Pioneer Cooking in Ontario: Recipes from Ontario Historical Sites.7 Judging from this and similar works, the past can be divided into three parts: "olden tymes," "pioneer days" and "colonial days." How a cookbook that includes recipes from the kitchen of one of the largest and most elegant mid-nineteenth-century mansions in Ontario has any association with "pioneer days" (whenever they may have been) is beyond comprehension.

19 Worthwhile and well-researched publications on the subject of historical cooking and baking are unfortunately far outnumbered by those that perpetuate myths, half-truths and misconceptions and do little to advance our understanding of historical food. Among the former, however, are four works with more scholarly credibility: Beulah Barss, The Pioneer Cook: A Historical View of Canadian Prairie Food; Jane Carson, Colonial Virginia Cookery, Elizabeth David, English Bread and Yeast Cookery, and the republished edition of Amelia Simmons, American Cookery, 1796.8 In each case, historical recipes are put in context by an introduction, and the differences between modern and historical materials and methods are accounted for.

20 Significantly few of these well-researched works emanate from historic sites, which have a tremendous and largely unrealized potential to become laboratories and research centres for this kind of work. Carson's book, from Colonial Williamsburg, is a splendid exception to this rule. If research into historical food is to become the province of cooks as well as of textual scholars (and it must if it is to be valid), then it must be written not only from bibliographies and archival materials, but also from a place where food is cooked. The historic site with a working kitchen is and should be such a place.

21 Day-to-day interpretation in historic kitchens is often a dynamic and vital activity in which the efforts and initiative of individual staff surmount a general lack of research and scholarship. With the identification of a research methodology suitable for historic kitchens, this situation can only improve.

22 Although they are extremely popular with visitors, historic kitchens must now do more than simply please the public. If museums plan exhibits with a specific life span, there is no reason why historic kitchens should not commit themselves to changing their recipes every few years, perhaps even every few months. Properly introduced, this kind of change can demonstrate to the public that museum research is an ongoing activity and that even something as substantial as a period room is subject to change and modification. As Schlereth states,

Museological Implications of the Historic Kitchen

23 The definition of such a large and complex undertaking as living history could require an entire book, as Jay Anderson has ably demonstrated.10 However, the living-history movement may be defined succinctly as that branch of the museum community focused on interpreting social history that has most sought to be active, multidimensional, multisensory and very often, outdoors. Its practitioners have seen themselves as breathing new life into exhibits and whole museums and even creating new types of museums, such as working historical farms. Such sites have proved enormously popular, and their numbers have increased dramatically in the last three decades.11

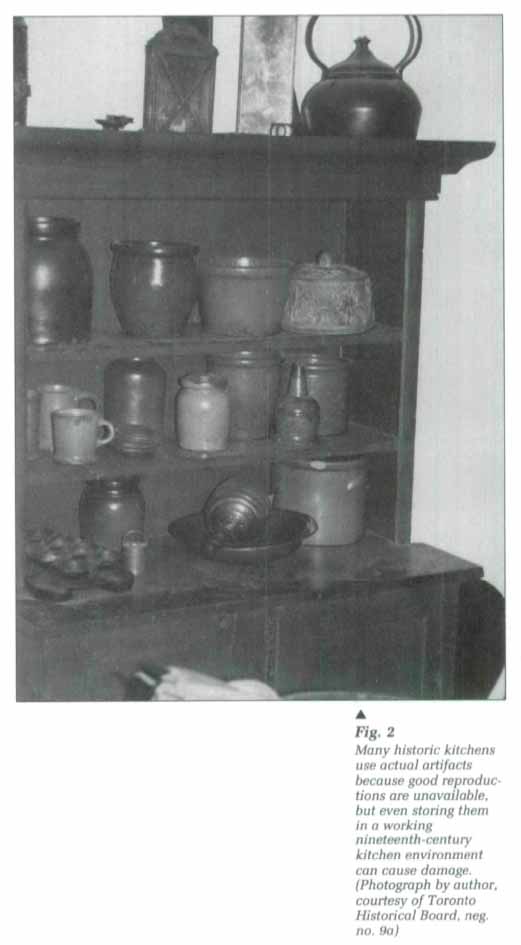

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 224 These new kinds of history museums, primarily outdoors, have developed innovative programmes to further engage visitors, ranging from demonstrations of activities to first-person role-playing by interpreters. The assumption that lies behind all of these programmes is that increased opportunities for activities and involvement for visitors will result in a better museum experience.

25 The restored working historic kitchen is a specialized area within this large rich field of living history. It is an active, participatory kind of "exhibit," where skilled interpreters demonstrate historical activities, but it also contains some aspects of the static period room from traditional gallery-style museums. It shares both the problems and the possibilities of living history as a whole. Historic kitchens have their "farbs," their tourist traps and their exemplary sites.13 They also have had to be largely self-policing with respect to historical authenticity; in the face of a public that loves any living history, there is perhaps little incentive to tackle this problem. As Anderson mentioned recently, the drive for greater authenticity and accuracy has come largely from within the ranks of living-history buffs, and not from the museum community at large.14

26 When researching in this area, or indeed in any area of museum work, one must enter a vast terminological swamp. "Historic kitchen," "restored domestic environment" and "pioneer kitchen" are terms often used to describe this type of living history. For the purpose of this study, the focus will be on only those kitchens where food is actually prepared with some attention paid to historical accuracy in materials, recipes and techniques used. Therefore, static period rooms and the modern kitchens often attached as support facilities to historic ones are excluded. This follows R.G. Chenall's system of classification wherein an artifact (or in this case, a site) is classified according to function.15 Thus this study is more concerned with what is done in and with a historic kitchen than how it looks or how old it is.

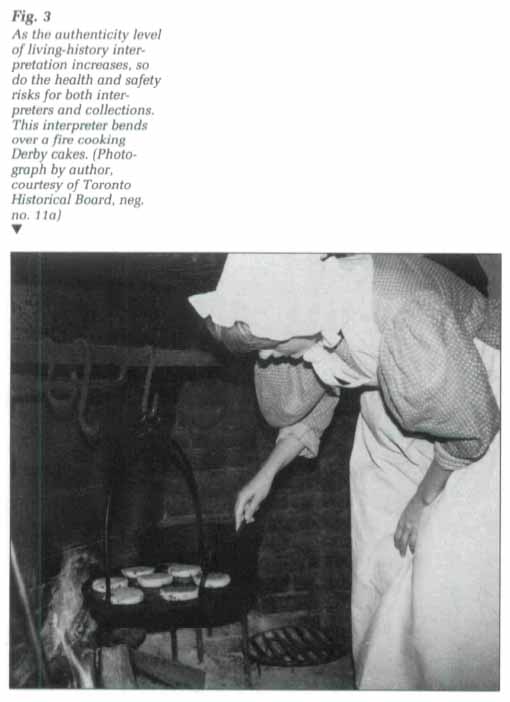

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 327 It is long past the time when those responsible for historic kitchens should broaden their conceptual base and abandon grandmother's recipes in favour of an interpretive approach committed to accurate and critical research. Suzanne Schell states that "research is the key to creating a credible interpretive program."16 Few would argue that this is the case. The quality, quantity and type of research, however, bear further analysis, as do the means by which the facts of research become a programme.

28 Historic kitchens are a distinct living-history form. Often overshadowed by the houses or sites that contain them, they are worthy of separate investigation. Once kitchens are seen as a specific discipline within living history generally, many questions are raised: Do they require their own research? From what other methods and disciplines can they borrow? What kinds of experiences do they offer visitors, and how are these similar to or different from other types of museums?

29 There is an existing body of research that supports the activities of historic kitchens. As Carl Benn said in the preface to an issue of the OMA Quarterly devoted to the papers from a 1979 symposium on food in mid-nineteenth-century Ontario, "From Garden to Table,"

30 Unfortunately it appears that this research does not often end up where it should, since the general quality of interpretation does not seem to match the supposed quantity of research. Benn makes this clear when he says later in the same preface,

31 Quantity is never quality, and while this research is not badly done, it may not be what historic kitchens need most at this point in their development. The orientation of the articles published after this preface offers an insight into why many Ontario sites seem to be stuck at a certain level, eternally baking cookies and substituting a "happy peasant" attitude for a comprehensive and critical understanding of the past.

32 In the first of these articles, Hilary Abrahamson provides a good overview of the problems of textual research into historical food, discussing cookbooks, private manuscripts, journals and other sources.19 However thorough her approach in this area, she neglects to discuss the actual preparation of the food contained in the recipes she researches, and her research is therefore incomplete.

33 Preparing these recipes is not simply something nice to do after a long day in the library; it is necessary to the complete understanding of the food. A researcher of historical food who does not cook as well as read is akin to a musicologist who does not play an instrument. The textual research is required, but it must be kept in mind that much information about food has always circulated through less accessible channels, such as word of mouth.

34 Another aspect of historical-food research that may differ from traditional academic scholarship has to do with dating. When a recipe is printed in a book (and this problem becomes more acute the earlier the period), it may well represent the end and not the beginning of its useful life. Recipes are similar to folktales and legends in their patterns of dissemination. Up to the early nineteenth century or later, depending on context, printed recipe books were rare due to both the conditions of their use and their relatively high cost, particularly in North America.

35 There are for instance only two extant copies of the 1831 Kingston edition of The Cook Not Mad held in Canadian rare book collections. An individual who did own a printed cookbook might lend it out for copying, and its recipes would circulate more widely in manuscript or by word of mouth. To say that the earliest printed reference to a recipe occurs in 1796 is thus to imply an existence far previous to that date. Even with the original textual source, which usually marks the end of a scholarly quest, the problems with historical food are therefore just beginning. A recipe such as this one from The Cook Not Mad is a paradigmatic case of the relative impoverishment of the textual record as a source for historical food.

Four eggs, four ounces sugar, one lemon grated with the juice, mix with four ounces butter, one cup of cream, baked in a paste.20

36 Oblique and enigmatic, it tells at best only half the story. What does this look like? What does it taste like? What was it made in? How long could it be stored? How much did it cost to make it? How was it served? How was it eaten? Do they mean old English or Imperial ounces? Relying too heavily on one printed source to understand historical food is like trying to encompass all of contemporary food preparation in North America from one battered and incomplete copy of The Joy of Cooking.

37 The historical recipe is a printed surrogate for an ephemeral artifact and must not be mistaken for the artifact itself. There is a strong performative element (drawing a musical analogy again) that is vital to a historical recipe's complete understanding. The printed historical recipe is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the museological and interpretive understanding of food in history.

38 To recover this ephemeral artifact, the living-history site requires tools, materials, skill on the part of the interpreter, and the kitchen, the largest artifact of all. This in turn entails training and commitment on the part of the staff, who should be researchers as well as interpreters.

39 The importance of the interpreter's skill seems to be commonly overlooked, as shown in Dorothy Duncan's "Restoring a Nineteenth-Century Kitchen," another paper from the symposium "From Garden to Table."21 She goes into some detail about textual and architectural necessities and devotes only a scant three paragraphs at the end to staff training and interpretation in the restored kitchen. Yet the necessary historically relevant skills must be developed to a high degree of efficiency, since only then will it be possible to generalize about such factors as how much work could be accomplished in a day in the kitchen.22

40 If one is training tour guides to stand outside the door of a static period room and deliver what Richard Erlich, Assistant Director of Plimoth Plantation, calls "the oppressively dull and vacuous harangues that are delivered at the front door of hundreds of historic house museums across the United States," little preparation is required.23 A prospective interpreter who is only full of facts about a site's dates and occupants will be completely unequipped to produce accurate historical food and discuss it with the visitor.

41 In short, then, it is up to the sites to do their own research, since only they have the tools with which to do it. It is this re-orientation, wherein the actual food becomes of equal importance to the textual source, which is crucial to the full development of the historic kitchen.

42 One hopes that the battles fought (and unfortunately still being fought) over material culture studies will not be duplicated as historic kitchens begin to produce unique research centered on the actual experimental production of historical food. Proponents of the study of artifacts as well as written records have in the past been looked down on by academic historians, who were convinced of the inherent superiority of the written word. Due in large part to the determined efforts of American scholar Thomas J. Schlereth, material culture studies is finally being given its due as a serious academic discipline.24 According to Andrew Baker and Warren Leon of Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts

43 Suzanne Schell recognizes the importance of producing things in a kitchen, as opposed to the reading of texts, and defines a key aspect of living-history sites when she says

44 A historic kitchen with a cooking hearth and/or a brick oven or woodstove can produce research that simply cannot be done elsewhere. The fact that any such site is likely to have staff who can operate these tools is an added bonus, since only day-to-day experience will recover some details of historical technology. Given the above, a positive flood of good material culture research should be pouring out of living-history sites. In the area of domestic work, however, this is simply not the case, perhaps because research is not seen as the role of these sites. If, however, historic sites and kitchens are truly part of the museum community, then they must not only produce but also publish good research. Research is not incompatible with interpretation and will, in fact, enhance it.

45 The notion of process addressed by Schell, of an ephemeral artifact or the process of its production having as much validity as a traditional artifact, is one of the building blocks of a revitalized historic-kitchen programme. In the hierarchy of museum objects, reproductions are often seen as inferior to the venerated "real thing": visitors are sometimes disappointed when they find out that it is "only a reproduction."27

46 In the case of food, however, these priorities and expectations can be successfully reversed, if not merged. Food produced in a historic kitchen with accurate techniques and materials occupies an ontological grey area: neither real thing nor copy, it is forever reproduced anew from the stable source or matrix of the recipe. Thus, the work of such a kitchen is related to other museum work wherein the use of reproductions is a conscious choice, not because originals are too rare, fragile or simply lacking, but because reproductions have benefits of their own.

47 Such is the case with the idea of the "sacrificial reproduction." In a review in Museum Quarterly, Thérèse Beaudoin describes an exhibition of mannequins in reproduction period clothing depicting ship construction in Québec from 1800 to 1850 and justifies the use of reproductions on the grounds that it satisfies the visitor's desire to touch and allows him/her to feel, to manipulate, to "see with the hands" the different materials used in making clothing of that era.28

48 The idea of "seeing with the hands" is a powerful interpretive tool and a useful conceptual framework for planning programmes. Visitors often persist in touching even when they are prohibited from doing so. If this desire is taken into account when planning programmes, visitors will be more likely to touch creatively and less likely to leave chewing gum under the edges of period tables.

49 Historical food is certainly such a sacrificial reproduction. The sheer ephemerality of food encourages and even demands touching through consumption. Food is all the more valid as an interpretive tool since the visitor's touch can provide the vital spark that brings this ephemeral exhibit into being. This is a singular opportunity for museums to create and not simply to legitimize existing artifacts through the pomp and circumstance of display in cases and galleries.

50 If a historic kitchen is to function as outlined above, fulfilling all of its potential, then the interpreter's role must become more complex. Interpreters are sometimes known as "animators." Derived from the French animateur or animatrice, the word means someone who instigates or provokes.29 The participants in this interaction then become the visitor, the animator and the food, giving rise to a semiotic triangle, in which the historical food is the message that completes an interaction between sender (animator/interpreter) and receiver (visitor).

51 It can therefore be seen that although a historic kitchen is only a part of the total museum community, and a discipline within living history, its operation raises many fundamental issues, from the role of the artifact to the quality of the visitor's experience.

Research in Historic Kitchens

52 In the course of an analysis of some of the problems surrounding the operation of living-history museums, Robert Ronsheim makes the following claim:

53 In a philosophical sense, Ronsheim is entirely right. The experience of another is ultimately unknowable, locked as we are into a subjective, temporal perception of the world. Although he states the case for not being able to entirely replicate the experience of the past accurately, Ronsheim does not take account of the possibilities as well as the shortcomings inherent in living history.

54 Surely the perspective of a modern person examining the past is valuable precisely because it is not the same as that of a historical person. The British foot soldier involved in the War of 1812 would probably have cared very little that the war seems, post hoc, to have been one of the strongest forces in creating an emerging sense of a uniquely Canadian identity. Were he alive today, he certainly could not give the tour of Fort York given by his modern, costumed counterpart. The scope of any one individual's knowledge is far smaller than the interpretive message of a historic site, and thus, if an interpretation is truly first person, it places severe restrictions upon the information that can be conveyed.

55 Ronsheim's last statement, concerning the material re-creation of history, is also debatable. The technical, as opposed to the affective, side of living history is one of the most exciting areas of present and future research. The controlled re-creation of past materials, skills and technology has become a discipline in itself, known by a number of names, including experimental archaeology, action archaeology, living archaeology, imitative research, experimental research and replication research. None of these completely expresses the scope of present work, and all are slightly misleading, for while the techniques may have originated in archaeology, they are now much more widely applied.

56 Born from experiments begun in the later decades of the eighteenth century, experimental archaeology has matured and developed to the point where its practitioners now perform experiments on subjects ranging from Viking ships to Iron Age farming methods. How does this fit in with a historic-site museum? As already stated, material culture research and an examination of "the ways in which objects can be used to reflect and amplify our collective experience" are basic tasks of history museums.31 The discipline of experimental archaeology is a useful methodology for the work that follows from this acknowledged importance of our material culture to living history and the research function of all types of museums.

57 By combining a rigorous, scientifically based methodology with the detailed examination of "the thing itself," which is so important to museums, experimental archaeology bridges the gap between the museum and the laboratory, most often by making the museum (or the historic site) into the laboratory. Describing one such experiment begun in the mid-1970s, Callender says that

58 With the steady increase in the sophistication of many historic-site museums and a growing awareness of the need for solid research to balance the inherent theatricality of living history, it is no longer necessary for sites to disavow their status as a museum in order to make use of "serious investigators." This kind of investigative research often seems to work better in the public eye and is entirely compatible with the wide range of interpretive and educational activities usually undertaken at historic-site museums.

59 Much attention has been focused on the larger projects of experimental archaeology, such as epic voyages in re-created ships or the operation of an entire historic farm. The same quality of experiment, the same intensity of experience and the same validity of data can be obtained from much smaller-scale experiments relating to recent history.

60 John Coles outlines three kinds of experiments that have been performed to date by experimental archaeologists, all illustrating what he calls "the fundamental importance of the experimental approach."33 The first kind of experiment is the simulation, wherein

Based on published recipes and the activities of historic kitchens, most historical foods now produced fall into this class. The necessary "copy" is made that fulfils the need of the historic kitchen, but the time spent preparing, displaying, interpreting and consuming the food cannot yield any further valid data, even for something as basic as taste because of the lack of control of the ingredients and methods.

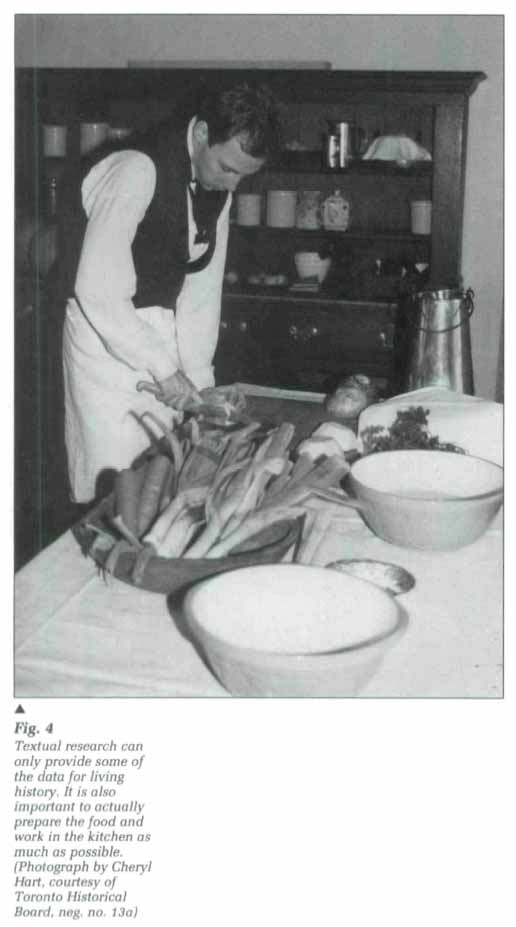

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 461 In the second kind of experiment, there is a greater concern for producing data as well as an end product.

For this, the appropriate methods, materials and technology must be used. Some historical-food research is organized this way, as for example when vegetables or grains are backbred to achieve historically accurate strains. Coles refers to this type of experiment as "testing for processes and production methods used in the past." For a historic kitchen, this might mean mastering the techniques of brick-oven baking, making sure that the oven, the door, the tools and the firewood are all appropriate.

62 The third type of experiment examines the functioning of the artifact itself. This is predicated on the accurate production of that artifact. For instance, it is difficult to discuss the taste and nutritional value of bread without producing it under proper circumstances with appropriate ingredients. For a historic kitchen, this type of experiment depends upon the crucial dimension of the interpreter's skill. We do not know what distortions and alterations occur, for instance, when a pair of twentieth-century hands knead eighteenth-century bread, and what effects this may have on the finished product:

63 It is necessary for an interpreter from the late twentieth century, the era of whole and unprocessed foods, to remember that such staple items as bread and sugar were differentiated along class and not nutritional lines in earlier times. Brown bread was the staple of last resort for those who could not afford anything better and a nutritional argument for its use was not popularized until the latter half of the nineteenth century.37

64 A consequence of the development of real skill among interpreters, who should perhaps in certain cases be called "historical technologists" to clarify their roles, is that experiments can be repeated so that conclusions are drawn from a large body of data. This is crucial if generalizations about working conditions and production are ever to be made. We cannot now accurately assess how difficult the work of the open-hearth cook was in measurable terms or how much one person could reasonably be expected to accomplish, yet such facts are crucial to interpreting the historic kitchen as a work environment.

65 The conclusions to be drawn from these kinds of experiments are not hard and fast and require corroboration through repetition and the sensitive interpretation of the data thus produced. From these general categories, and experience gained in experiments performed to date, Coles offers eight rules for the conduct of experimental archaeology. These apply to all experiments, from stone-tool making to open-hearth cooking.

- The materials employed in the experiment should be those considered to be originally available to the society under examination.

- The methods used in the work should be appropriate to the society and should not exceed its presumed competence.

- Modern techniques and analytical studies should be carried out before, during and after the experiments.

- The scale of the work must be assessed and fairly stated.

- Repetition of the experiment is important in order to avoid a freak result.

- During each experiment certain problems will be examined in the hope of gaining answers. But improvisation should be considered; and adaptability is of paramount importance.

- Experimental results must not be taken as proof of ancient structural or technological detail.

- The experimenter must assess the results of the experiment in the following terms: Were the materials right? Were the methods of using them appropriate? Were mistakes made? Were procedures recorded accurately? Was the experiment affected by personal opinion, idiosyncrasies, preconceived ideas, short-cuts, laziness, tiredness, boredom, over-enthusiasm?38

A ninth obligation, particularly important for museums, is the accurate and critical publication of results to the public and other professionals in the scholarly community.

66 Some research relevant to domestic history is underway which partakes of Coles' methodology. One particularly provocative example is the work at the Colonial Pennsylvania Plantation. A colonial kitchen is maintained and operated as part of the plantation, and the rate of trash accumulation for this kitchen has been carefully documented.39 This modern accumulation will eventually be compared with a similar historical trash pit. The experimenters are aware of potential distortions, discussing the effect of such factors as the skill of the cook on trash accumulation and breakage.

67 Barbara Riley offers a useful typology of food-related activities which could help to organize future domestic experimental work. She divides this area of research into "obtaining, storing, preparing, preserving, consuming and disposing of."40 From this list and the programmes observed previously in this article, it can be seen that present domestic interpretation and research at living-history sites focuses mainly on preparing and that many other areas of work are possible.

68 In the course of her research, Riley spent a day working in the kitchen of The Grange as an interpreter. Summarizing that experience, she focuses on the technical aspects of the job, saying, "My apprenticeship provided insights into the technology of open, wood-burning fires used to prepare food." She clearly identifies even something as basic as an open hearth as a primarily technological research problem and points once again to the skills that prospective interpreter/researchers must be expected to master.

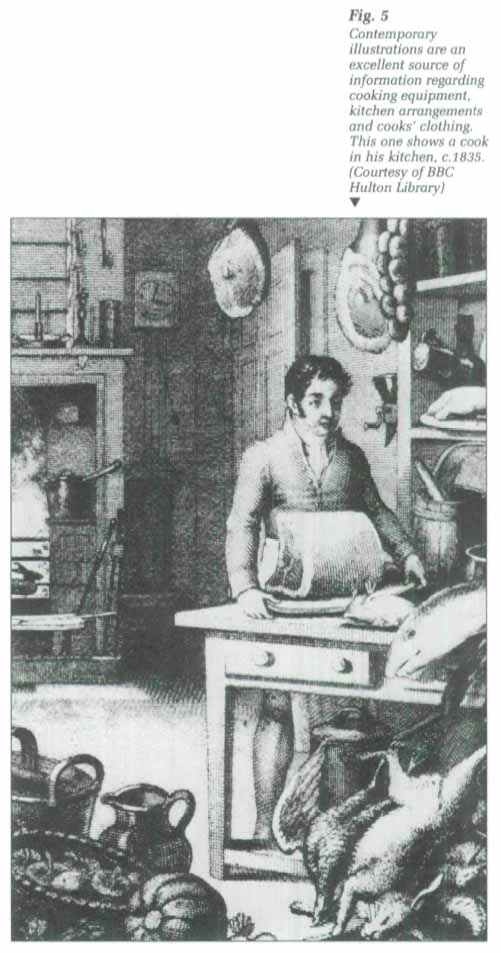

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 569 It may be argued that many sites do not have the time and personnel to carry out an advanced research programme such as this. After all, they exist primarily to serve the public by giving tours and interpreting, and not for the purposes of obscure research. As long as "research" is seen as something done before the doors open, or in back rooms for "staff only," this may be true. However, historic-site museums have nothing to lose and everything to gain by making their research an integral part of their programming and by having it done by the same people who do the interpretation. James Deetz makes this clear:

Deetz's comments in reference to exhibits can just as easily be applied to historic-site interpretation, with the advantage that an interpreter, and not a label, can explain "how we found out what we know."

70 Ronsheim includes in his discussion of the problems of living history the admonition that "visitors should be helped to perceive the difficulty of understanding what life was truly like in the past."42 Knowledgeable, skilled interpreters can easily perform this role. By showing that museological research at historic sites is complex, multifaceted, active and ongoing and that visitors may not see the same museum when they next return, historic-site museums and the people who work in their kitchens can only increase public awareness and understanding of what they do.

"Big History" and "Little History"

71 The history that is learned and written through the practice of living history is of two kinds, which might be termed "big history" and "little history." By attempting to produce food, raise livestock, inhabit dwellings and make and use tools under historical circumstances, we can understand the larger consequences of these technologies and interpret them to a wide audience. This is big history; it moves outward from the individual interpreter to a whole country. This kind of history can be scientifically based. In a controlled experiment at a living-history farm, examining the harvest yields of historical wheat strains can help us understand the rise and fall of an entire community, moving then from an individual head of wheat to a national or international level of history.

72 The practice of living history yields as well smaller insights and conclusions. While the archaeologist gathers use-wear data from the grinding of wheat or corn in stone churns, the individual doing the grinding, the living historian, is gathering data of his/her own— the experience of grinding that corn. This is little history; its conclusions may not settle academic arguments or rewrite history, but they may lead one individual to a better understanding. Thus big history offers data that no one individual in a given historical society could possibly have known. This is the total "message" of most historic sites, a combination of many different kinds of research. Little history offers the data of nerves, hands and muscles.

73 To date, historic kitchens have given a sometimes uneasy mixture of both kinds of history. By ensuring that the methods, tools and materials of daily work are as accurate as possible, the big history that the kitchens write will be based on reliable data from the little history that inevitably builds up as interpreters perform their daily tasks. It is important that interpreters come to see themselves as writing this kind of history.

Conclusion

74 Historic kitchens have meant and will continue to mean many things to many people. To older visitors, whose grandparents may have made use of the technologies we interpret, they are a powerful force for awakening memories, at least for one more generation. To young children, they are a vivid experience which is often intensely real. Children will compress time, asking in all seriousness if the arrangement on the table is the same food people left there over a hundred years ago. For them, there is no discontinuity between past and present, and our task is to make them better understand concepts of time and history. To its practitioners, living history, in kitchens and in general, is often fun, a job they jokingly refer to as an escape from the "real world."

75 At the core of these different experiences is the kitchen itself. Whether the kitchen's activities are supported by a solid base of research or not, these experiences will continue. Nostalgia does not need facts and indeed is often hindered by them. A cooking class of children will never offer an informed critique of our handling of historical-recipe conversions. It is therefore incumbent upon those who work in these kitchens to ensure that this most powerful and vivid experience is offered in good faith, based on solid research and good information. Sometimes, this may mean nothing more than being aware of one's own modern biases in re-creating a historical process. In other cases, it may mean participating in a full-scale research project. It is hoped that the next few years will see a dramatic increase in the amount of scholarship, experimental research and critical thinking taking place in historic kitchens.

This article is based on my 1986 Masters of Museum Studies thesis at the University of Toronto.