Articles

Crucial Trends in Modem Ukrainian Embroidery

Résumé

Du point de vue synchronique, la broderie populaire ukrainienne dans le Canada d'aujourd'hui obéit à un ensemble de forces binaires axées sur trois éléments : la couleur, le dessin et la fonction. Les manifestations non matérielles de la culture populaire ukrainienne au Canada, comme la chanson. renforcent certains éléments; et une tension entre représentation réaliste et abstraction géométrique se dissipe actuellement en faveur de cette dernière tendance. La recherche à long terme, les études sur le terrain et diverses collections montrent la transformation de la broderie populaire ukrainienne en un logogramme stylisé qui souligne la fidélité de la communauté ukrainienne à ses traditions. Ce phénomène pourrait compenser, dans une certaine mesure, l'abandon graduel de l'ukrainien comme langue fonctionnelle chez les Canadiens d'ascendance ukrainienne.

Abstract

From the synchronic point of view, Ukrainian folk embroidery in Canada today operates in keeping with a set of binary forces that indicate a basic concern with three features: colour, pattern and function. Non-material manifestations of Ukrainian folk culture in Canada. such as songs, reinforce certain features; a tension between realistic representation and geometric abstraction are being resolved in favour of the latter trend. Long-term research, field studies and various collections show the transformation of Ukrainian folk embroidery into a stylized logogram that underlines the Ukrainian community's allegiance to its ethnic heritage. This phenomenon possibly compensates, to some extent, for the gradual loss of Ukrainian as a viable language among Canadians of Ukrainian descent.

1 Traditional embroidery constitutes one of the most popular manifestations of Ukrainian folk art in Canada today. This grass-roots enthusiasm has been commercialized with considerable success and is reflected in the transfer of Ukrainian cross-stitch design via print, decalcomania and wood-burning techniques onto a variety of non-traditional surfaces; without needle or thread, glassware and ceramic items of all kinds (ranging from coffee mugs to ashtrays), lamp shades, toaster covers, business cards, photo albums and T-shirts are made to look as though they have been embroidered.

Display large image of Figure 1

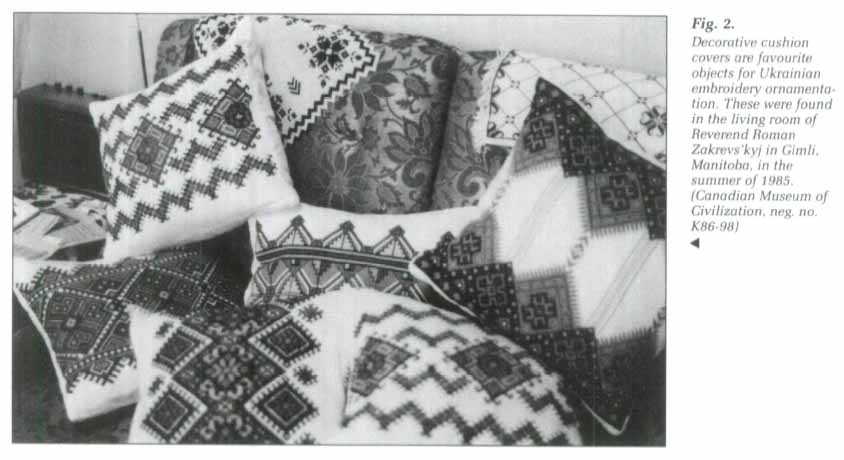

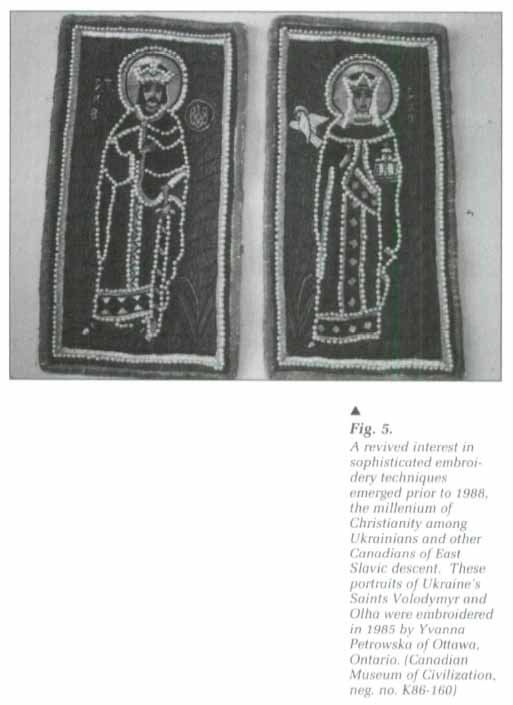

Display large image of Figure 12 Works on traditional Ukrainian embroidery techniques have been published in this country since the 1930s2 and important collections of Ukrainian folk embroideries are now found across Canada.3 These tend to focus on secular uses of folk embroidery as a form of ornamentation on such textile items as shirts (female rather than male shirts invariably dominate this particular genre), ritual towels (rushnyky)4 and cushion covers.5 Examples of a more eclectic approach to the application of traditional Ukrainian folk embroidery are found in the national collections of the Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, a division of the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Ottawa-Hull; these include domestic incidental items such as book marks and ladies' purses. As noted elsewhere,6 sacred or religious embroideries are underrepresented and often ignored in spite of their productivity. In recent years, specialized studies devoted to traditional embroideries have been published;7 and in North America, exhibitions featuring Ukrainian folk embroideries appear from time to time.8

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 23 The study of Ukrainian embroidery is especially conducive to romantic speculation and parochial sentiments. Prehistoric and pagan motifs are assiduously noted and, along with certain other elements, traced to particular villages and districts in the Ukraine. Purists consider regionally defined features inviolable but fail to broach the nature of geographical distribution in Canada.9 The diachrony and descriptive eclecticism that characterize these approaches to the study of Ukrainian folk embroidery show a great deal of appreciation but avoid questions of contemporaneity.

4 In Canada, the old distinctions between folk/village/secular embroidery on the one hand and sophisticated/religious embroidery on the other is blurred.10 Nonetheless, it remains an activity dominated by female practitioners;11 in this connection, psychoanalytic techniques could be adopted to determine whether (and to what extent) this form of Ukrainian folk art parallels the Ukrainian lullaby corpus12 and functions covertly to provide a socially approved outlet for the expression of suppressed tension and hostilities. Such approaches to the analysis of Ukrainian embroidery, however, remain underdeveloped and highly speculative— albeit suggestive.13

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 35 Simplification and standardization constitute the leading trends in contemporary Ukrainian folk embroidery in Canada; stitchery, for example, is almost universally confined to cross-stitch (khrestykamy). Nowadays the tradition operates in terms of binary forces that in isolation and/or in combination with one another obtain as a set of productive tensions. In essence, Ukrainian folk embroidery has come to concern itself with colour coding, pattern and function.

Colour

6 In effect, the table of traditional colours is currently limited to three: white, red and black. The colour white is almost exclusively provided by the cloth itself and it gives a highly contrastive backdrop for the superimposition of ornamentation in terms of red and black thread embroidery. These two colours, red and black, are imbedded in the popular psyche of all Ukrainians14 and received added recognition in the 1960s when a popular, sentimental song, "Two Colours" (Dva kol'ory), reached the Ukrainian community and became an instant "hit" everywhere. My English translation of the text follows:15

One spring when I was young

I set out along unknown paths:

My mother embroidered a shirt for me

With rod and black,

With red and black threads.

O my two colours, two colours,

Both on cloth, both in my soul,

O my two colours, two colours:

Red-that's for love,

And black—that's for worry.

But I returned to my own ways,—

Like mother's embroidery, my happy,

My happy, my happy and sad paths

Intertwined with one another.

But I bring nothing home

Except a small roll of old cloth;

My life is embroidered,

And my life is embroidered on it.

Pattern

7 In general, Ukrainian folk embroideries produced in Canada show two types of preferred stylizations: realistic representations and geometric abstractions. Both kinds of configurations often combine to engage in a form of interplay that is mutually enriching. In all cases, however, the tradition in Canada operates in keeping with certain determinants rather than haphazardly. In this regard, function, purpose and intent are paramount factors, as shown, for instance, in the tendency for male embroiderers and embroidery on masculine apparel items (such as men's shirts. fobs and neckties) to prefer geometric compositions.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 48 Ukrainian folk embroidery does not seek to duplicate reality. Instead of focusing on a single, isolated representation of some real form (floral, human or other), this art revels in the hypnotic attraction of endless repetition. The effect is achieved both physically and optically by using a seemingly infinite number of tiny embroidery stitches and, on a larger scale, by the predilection for geometric motifs, figures and elements in either linear or scattered fashion. Currently the tension between realistic representation and geometric abstraction is being resolved in favour of the latter trend, which avoids the issue of a judgmental comparison with the real thing or person. Often when realistic motifs do appear, they do so only incidentally within the context of a larger configuration that dominates as the true centre of attention.16

Function

9 From the operational point of view, Ukrainian folk embroideries in Canada obtain in two kinds of settings: closed/personal and open/ public. The closed/personal category of milieu is almost totally eclipsed by the public function of Ukrainian embroidery, which is maintained chiefly as a form of open display to underline a fidelity to ethnic loyalty and origins.17 This public function of Ukrainian folk embroidery and its concomitant politicization is reflected in many of the Ukrainian embroidery items housed by the Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies at the Canadian Museum of Civilization; those demonstrate the emergence of modern-day Ukrainian embroidery as a symbolic motif that carries with it an emblematic function. The diverse application of Ukrainian embroidery motifs, noted earlier, points to the use and widespread acceptance of Ukrainian folk embroidery as a king of unofficial but popular logogram. The ideogrammatic use of three colours (white, red and black), discussed above, reinforces the open/public function of Ukrainian embroidery that along with ornamented Easter eggs (pysanky)18 permeates the Ukrainian Canadian community's entire range of expressive behaviour.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 510 To sum up, then, the basics of Ukrainian folk embroidery in Canada may be defined as: the use of selected colours in conjunction with geometric configurations to produce an embroidery that is sufficiently emotive and powerful enough to serve as a visual ethnopolitical statement. It is possible that the predilection for geometric motifs compensates to some degree for the gradual loss of the mother tongue among Ukrainian Canadians19 by its transformation of Ukrainian embroidery into a kind of calligraphy that bespeaks group continuity, allegiance and pride.