Reviews / Comptes rendus

Vancouver Museum, "Captain George Vancouver: A Voyage of Discovery"

1 Vancouver's centennial celebrations brought Vatican, Dutch, and Egyptian art to the city's gallery and the Expo 86 site. The University of British Columbia's Museum of Anthropology featured Jack Shadbolt's Indian motifs and a Bill Reid retrospective. The most appropriate exhibition, however, was the one at the Vancouver Museum honouring the eponymous father of the city, Captain George Vancouver, and his voyage of exploration, survey, and diplomacy.

2 Vancouver sailed from Falmouth on 1 April 1791 aboard the Discovery, accompanied by the smaller Chatham. When he arrived back from the Pacific in October 1795, he had covered about 65,000 miles (his boats another 10,000), secured the cession of Hawaii, surveyed and charted the western shore of the North American continent from Cape Mendocino in present-day California to Cook Inlet in Alaska, and begun his narrative of the voyage that ranks next to Cook's as the most important eighteenth-century publication on the North Pacific and next to none for the Northwest Coast.

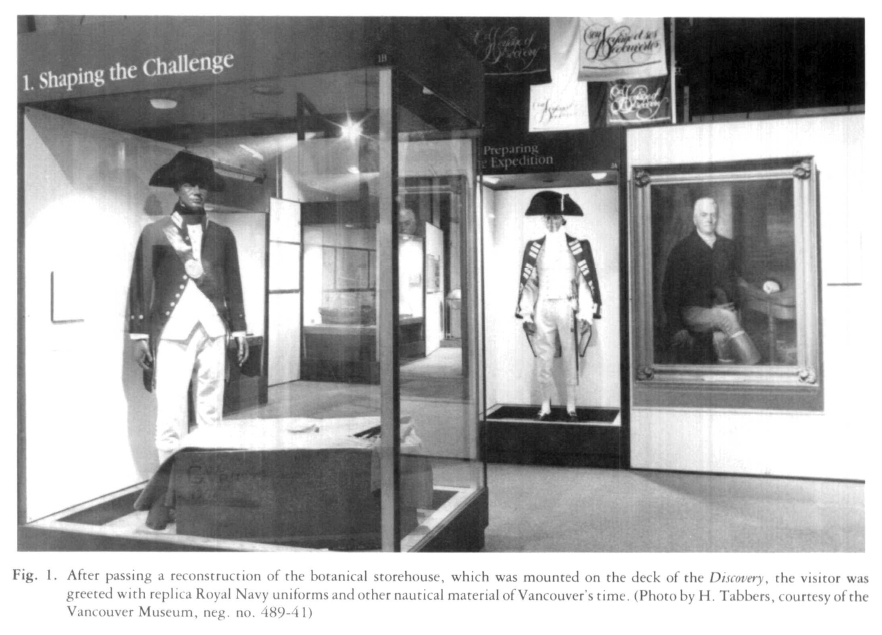

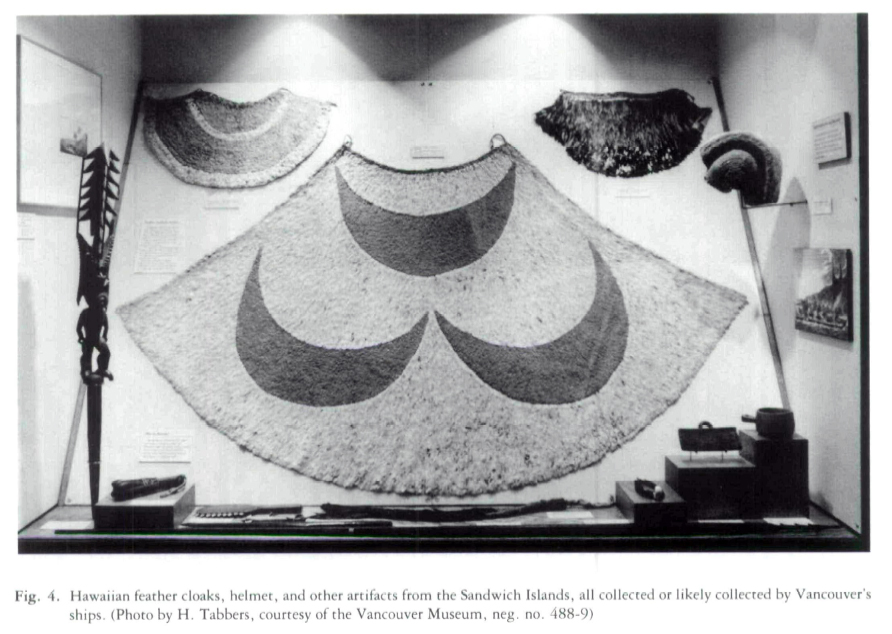

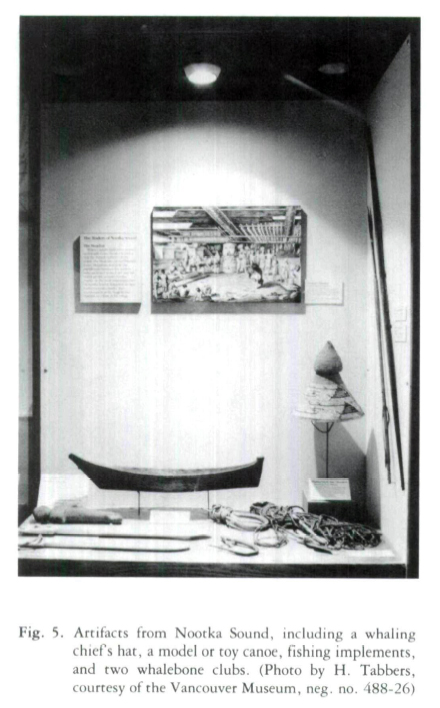

3 "Voyage of Discovery" offers the viewer very impressive material. Almost nothing conceivable to the imagination is missing: charts, drawings, and logs are there, along with original and representative instruments, marine tools, and ship models, and natural history specimens and ethnological objects from California to Alaska and from the Marquesas to Hawaii. The strength of the material makes it difficult to single out one item as particularly outstanding. Perhaps the most striking artifacts are the four Hawaiian feather cloaks, at least two of which were collected on the voyage. Some will be more impressed with the four chronometers — all those that accompanied the expedition. But can one overlook the drawings of Vancouver's midshipmen — Thomas Heddington's of the Spanish settlement at Nootka and John Sykes's of Cheslakee's village or his lovely watercolour of a Kauai village? Or Vancouver's letter announcing to visiting ships that Hawaii was, as of 1794, under the protection of the British Crown? The re-creations of shipboard life and costume appeal especially to children, though all will be impressed with the authenticity of some of the material, including several impressive eighteenth-century articles lent by the company that recovered the remains of the sunken supply ship Invincible. Little, then, is ignored and less neglected. Nevertheless, the strength of the exhibition probably lies less with the marine and voyage memorabilia than with the artifacts representing the other side of the exploration — the native societies visited. Hawaii, where the ships wintered annually, is best represented.

4 George Hewett, surgeon's mate on the Discovery (and Vancouver's most severe critic), made the largest collection, now in the British Museum of Mankind. It includes a marvellous Tahitian feather gorger, a Hawaiian tooth anklet, two of the feather capes, and most of the Northwest Coast material, including a Clayoquot whaling chiefs hat, a Bella Bella paddle painted in classic north-coast style, and a rare Klallam Salish mountainsheep horn rattle.

5 "A Voyage of Discovery" remains, however, an encyclopaedic exhibition. This is both its strength and its weakness. The comprehensiveness allows a wealth of quality artifacts, but at the expense of thematic cohesion. A viewer sees the navigation, natural history, ethnology, marine history, and hydrography, but no real theme emerges. The storyline, essentially narrative, is broken by necessary excursions into the difficulty of establishing longitude, the diplomacy of Nootka Sound and Hawaii, and the ethnology of New Albian. While such fragmentation may be unfortunate, it was probably unavoidable. The thematic vacuum is the necessary result of a voyage that had various assignments and multiple results. A few threads might have been tied more conclusively and the exhibition might have aimed more at assessments of the voyage's significance.

6 Curator Lynn Maranda has built upon a secure edifice of scholarship, most notably W. Kaye Lamb's fine edition of Vancouver's journals, published in 1984 by the Hakluyt Society. Yet the exhibition gives the voyage's "main task" as "the search for the Northwest Passage." The British government had, as Lamb points out, various reasons for dispatching Vancouver to the Pacific, including a concern with bases for whaling in the South Pacific and, after the Nootka Convention with Spain, to receive back the lands and buildings purported to have been seized from John Meares at Nootka Sound. More generally, the government wanted to establish more firmly its claims of freedom of trade and settlement on the Northwest Coast and to gain more information about an area in which it had gone to the brink of war in declaring its interest. It wished Vancouver to secure, in his survey of the coast, accurate information on any water routes that might facilitate trade with British settlements on the opposite coast, but the government and Vancouver were both sceptical of the existence of any Northwest Passage. The expedition might be expected to find better trade routes between the coast and Hudson Bay or the St. Lawrence; it did not, however, expect to find any actual passage. Indeed, the task was less to search for one than to prove that none existed.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 17 To quibble about a single regrettable label would be pointless. An accompanying catalogue would doubtless have helped to clarify the various purposes of the expedition and to elaborate on other aspects of the voyage. A catalogue was planned, indeed prepared, but finances proved insufficient for its publication. Perhaps it can yet be salvaged, but too late to be of use to the exhibition. When it closes the exhibition will disappear, an object of remembrance more ephemeral than Expo 86. Not even a leaflet exists to guide the visitor or to perpetuate the memory.

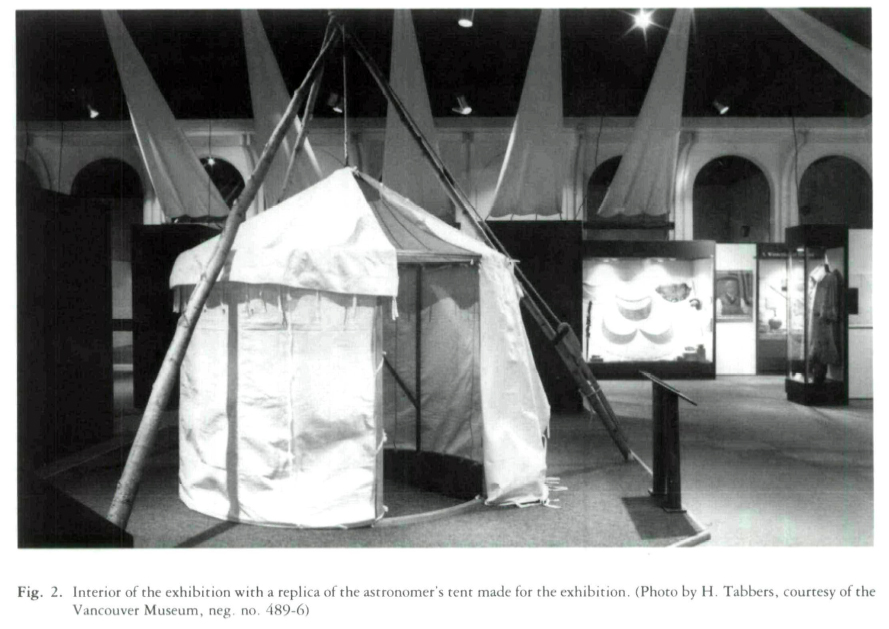

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 The fate of the catalogue reflects the difficulty with finances faced by the Vancouver Museum. Although it has mounted here an outstanding exhibition within budget. "A Voyage of Discovery" did not reach its full potential. The size of the show had to be cut at the last moment and the crunch of finances also meant lay-offs. Vancouver was a great explorer, his namesake is an equally great city. The Vancouver Museum has put on an exhibition worthy of both in spite of the financial difficulties.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Curatorial Statement

9 "Captain George Vancouver: A Voyage of Discovery" was the second in a series of temporary exhibitions presented by the Vancouver Museum featuring the early explorers of British Columbia. The first, "Discovery 1778: Captain James Cook and the Peoples of the Pacific," was organized as the museum's 1978 contribution to the province-wide Cook bicentennial celebration. Vancouver had served under Cook from 1772 to 1780; thus it was a natural conceptual progression to prepare and present an exhibition highlighting the career and achievements of this second great maritime explorer.

10 Work on the exhibition began in 1979 and by early 1980, staff, in committee, decided that the Captain Vancouver project would be mounted in 1986 as a corollary to the city of Vancouver centennial, though the bicentennial anniversary of the explorer's own contact with the Pacific Northwest would not be until 1992. Borrowed material would also be in less demand from multi-institutional sources in 1986 than in 1992 — a lesson learned from the demand placed on Cook ethno-graphic artifacts in 1978.

11 The main objectives of the project were to capitalize on the concept initiated with the James Cook exhibition; to create a world-class, interdisciplinary exhibition on George Vancouver and his own 1791-1795 voyage to the Pacific; to offer the visitor an innovative, rich, comprehensive presentation in a wholly unique experience; to bring together, for the first time in two hundred years, materials used, prepared, and collected during the voyage; to add to the very small body of literature relating to Vancouver's voyage by producing a written record of the exhibition in catalogue or larger publication form; to provide a fitting tribute for the city's centennial

12 The material displayed broke new ground for the museum world as this was the first time in two hundred years that original artifacts, specimens, documents, drawings, maps, and charts relating to Vancouver's voyage had been assembled under the same roof. This achievement in itself was the major highlight of the exhibition. On display were original plant specimens collected, prepared, and mounted by Archibald Menzies, naturalist and later, surgeon on the voyage. His herbarium sheets represent the first documentation of plant nomenclature and description for the Pacific North-west and these were shown, as were the only known extant colour drawings done by him. An exact scale replica of Menzies' shipboard plant frame was constructed and used to display living plant specimens of the species he originally collected and named.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 413 While the maritime history highlights included eighteenth-century navigational, surveying, and observatory equipment, the main achievement was the assembling and display of the four chronometers used aboard Vancouver's ship Discovery. One of these had also travelled with Cook on his last voyage. George Vancouver's own travel desk, borrowed from the descendants of his brother John, is one of the few extant artifacts associated directly with the explorer. A reconstruction of a ship's mess, to show one aspect of shipboard life, proved to be very popular, and its authenticity was created by the inclusion of many artifacts salvaged from the recently discovered 1758 wreck of the supply ship, HMS Invincible. The exhibition included the only known, albeit disputed, portrait of George Vancouver; many of the original drawings produced during the voyage; and a selection of notable documents, maps, and charts — for example, Vancouver's letter announcing that King Kamehameha had ceded Hawaii to Britain; Menzies manuscript journal; two charts drawn by Midshipman Vancouver, age 15, on his first voyage with Cook; and a list written by Thomas Dobson, Vancouver's Spanish translator, itemizing the ethnographic artifacts he collected during the voyage, some of which were actually displayed in the exhibition.

14 Although the known ethnographic artifacts of Vancouver provenance total only in the hundreds, some two hundred of these were displayed. Considerable attention was given to the peoples of the Pacific Northwest coast from the Chumash and Yurok in California through the Coast Salish of Puget Sound and Georgia Strait to the Chugach and Aleut in Alaska. The following were among the highlights of the ethnographic artifacts collected on the voyage and featured in the exhibition: feather-work from Hawaii including two full-length cloaks made of vegetable-fibre netting covered with red and yellow feathers; a ceremonial gorget with sharks' teeth and dog hair from Tahiti; woven baskets from California; mountain goat horn bracelets from the Coast Salish; wooden armour, a carved chiefs frontlet, painted basketry hats, and a carved antler comb from the northern Pacific coast.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 515 "Captain George Vancouver" was a world-class exhibition. The more than sixty institutions and individuals around the world that were contacted gave encouragement and support to the project by contributing more than three hundred rare, original objects to create a "first time ever event for the world" to happen in Vancouver.

16 The scope of the exhibition was realized through the talent and dedication of the curatorial team. For the research, contact, and persuasion needed, these individuals had to know the subject area well, otherwise locating material would have been impossible and borrowing items would have been unlikely as a high degree of diplomacy was required for such transactions. The exhibition was interdisciplinary and the associate curators (Dan Conner — Maritime History, Susan Moogk — Ethnology, Sharon Hartwell — Botany) supplied expertise from their subject fields. The result was that many firsts were achieved for the Vancouver centennial celebration. As well, in 1985 the Vancouver Museum received from the National Museums of Canada, Museum Assistance Programmes, the largest grant awarded to date for a temporary exhibition.

17 The majority of the stated objectives were met, though it is unfortunate that as yet the catalogue has not been published. It is still possible, however, to supply the Vancouver city centennial celebration with a record of its finest expression in 1986 and the international lenders with a record of the good use to which their material had been put, and it is expected that the catalogue will soon be available for the Canadian public.