Reviews / Comptes rendus

Environment Canada, Parks, Batoche National Historic Park.

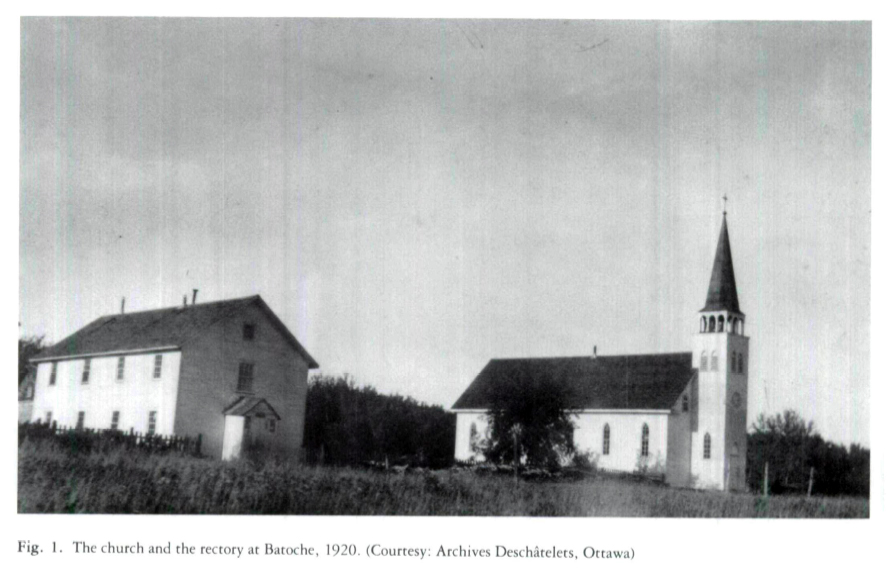

1 Whenever family or friends visited Saskatoon in the past, an afternoon drive to Louis Riel's headquarters during the 1885 Northwest Rebellion was a regular outing. Heading north towards Batoche along Highway 225, it was customary to pull off the road opposite Middleton's zareba and examine a scattering of rifle pits, visit the solitary grave of gunner Phillips, and take in a breathtaking view of the South Saskatchewan River and perhaps catch a glimpse of the white pelicans feeding below. From here, it was a short drive to the main parking area in front of the old rectory, and before your passengers were halfway out of the car, you were already pointing out the bullet holes still visible in the second story of the structure. At the site, you examined a simple, unpretentious display on the main floor of the rectory, peered through the church windows, walked down to the cemetery to Gabriel Dumont's grave and, maybe, had a picnic. Then, it was off to nearby Duck Lake and Fort Carlton or back to Fish Creek; rarely did you ever venture down to the site of the former village of Batoche, located almost a kilometre northwest of the rectory.

2 With Parks Canada's recent restoration efforts at Batoche, this low level of development and interpretation is now a thing of the past. Indeed, what has been done is quite simply startling in terms of the amount and nature of the changes, and as a result, visits have become a rewarding, potentially daylong affair.

3 First designated as a site of national historic significance by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board in 1923, Batoche was initially recognized as the place where heroic Canadian forces defeated a group of nameless rebels. Over the next few decades, the HSMB made various piecemeal recommendations regarding the site; some were acted upon, some not. The emphasis on the military campaign consequently dominated until 1970, when the Board, undoubtedly influenced by the changing attitudes of the time, finally declared that Métis social and economic lifestyle should also be interpreted at Batoche.

4 This recognition of both the military and socio-economic importance of the site was subsequently mirrored in Parks Canada's 1982 Management Plan for Batoche. Developed in consultation with various groups and individuals, including the Association of Metis and Non-Status Indians of Saskatchewan (AMNSIS), the plan essentially called for significantly improved visitor services and structural/landscape restoration over a two-phase development period. The first phase (1981-86), completed at a total cost of $7 million, was officially opened 18 May 1986, at which time Batoche was also designated a national historic park.

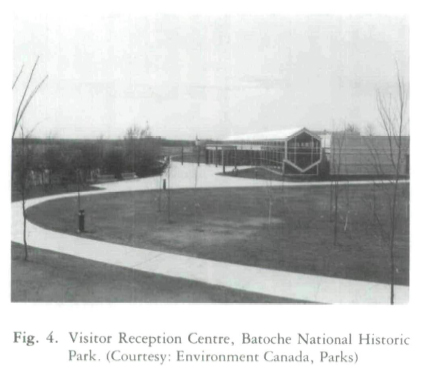

5 Several major features make up this first development phase. Besides relocating Highway 225 so that it no longer sliced through the middle of the site, all modern buildings were removed from the historic area. The majority of the on-site administrative/interpretive services are now housed in a new Visitor Reception Centre at the eastern edge of the park. (Note that until recently Batoche was administered by the Area Superintendent at Fort Battleford National Historic Park, 140 km northwest of Saskatoon.)

6 The new visitor centre is an ultra-modern, deceptively large, glass and metal structure that could easily be mistaken from the distance as a greenhouse. It contrasts completely with the historic features of the site and seems totally out of place. Once inside, however, it soon becomes apparent that the architecture allows the visitor to maintain almost constant visual contact with the historic landscape. And when the visitor leaves the building, the sense of stepping back in time is reinforced.

7 The two main features of the visitor centre are the audio-visual presentation and the exhibit hall. Both are organized around the park's two historic themes: the Northwest Rebellion of 1885 and Métis settlement in the Batoche district. The 45-minute audio-visual presentation, delivered alternately in French and English in an 80-seat theatre, consists of an original musical score (too loud), specially commissioned paintings, spotlighted mannequins portraying different personalities, a bank of 18 synchronized slide projectors, and a large scrim. These features combine to produce a visually pleasing, totally absorbing presentation that must be seen before exploring the park. The producers and designers are to be commended. At the same time, the story of Batoche and the rebellion tends to be simplified at times. The Métis are presented as contented, carefree buffalo hunters who like to dance; the viewer does not get an accurate sense of the diverse and stratified society that existed at Batoche. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, on the other hand, is reduced to pounding his desk in fits of anger against Riel. And in a serious oversight, there is no mention in the closing credits of the historians who worked on the project.

8 The exhibit hall is divided into two sections. Drawn into this area by an attractive mixture of Indian and white cultural artifacts, the visitor finds a series of panels on the fur trade and the winterers, the Red River Settlement and the annual buffalo hunt, and the 1869-70 resistance and the subsequent move to the Saskatchewan. The two dominant features of this area are a life-sized diorama of a Métis buffalo hunt in the Saskatchewan district in the 1850s (prepared by the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature) and a large display case, full of a number of fascinating items representing the socio-economic lifestyle of the Batoche Métis (goods from Xavier Letendre's store, agricultural implements, toys and games, religious objects).

Display large image of Figure 1

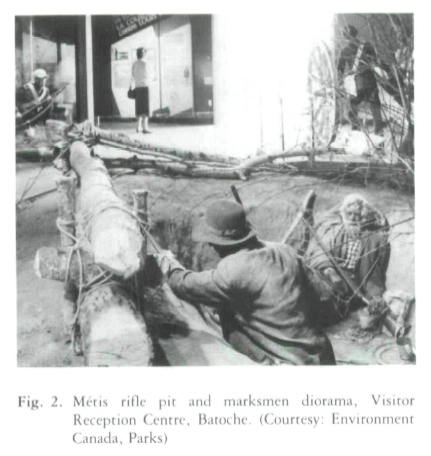

Display large image of Figure 19 The visitor moves from here to the other major section, "War in the West." At the beginning of this second theme, there is an introductory panel on the issues and leaders of the rebellion; unfortunately, the storyline does not adequately explain the circumstances behind the uprising. What follows, however, more than compensates for this shortcoming. There are models of the Métis crippling of the SS Northcote on 9 May 1885 and of the final charge of the Canadian forces three days later. Dioramas of a Métis rifle pit with two marksmen and of a gunner with a nine-pound rifled muzzle loader are included. In addition, there are displays on the strategy and tactics, as well as on weapons and dress of the two sides. What is most interesting, though seemingly little studied, are a series of maps of the four-day battle at Batoche. These carefully researched maps demonstrate why the Métis considered the first day of hostilities a success and help make sense of the historic landscape and how it was used by the combatants. In fact, taken together, the two exhibit sections provide a balanced, informative account that goes a long way to correct the one-sided interpretation of the past. It is too bad that this sensitivity does not extend to the display's concluding panels. Here, the visitor rightly learns that Batoche was not snuffed out by the rebellion but thrived until the 1920s. The treatment of the rebellion aftermath, however, is cast in terms of French-English/Catholic-Protestant conflict; not only does the exhibit make the historiographically outdated link between the execution of Riel and the victory of the Laurier Liberals in 1896, but it also says little, if anything, about the significance of the rebellion to Western Canada.

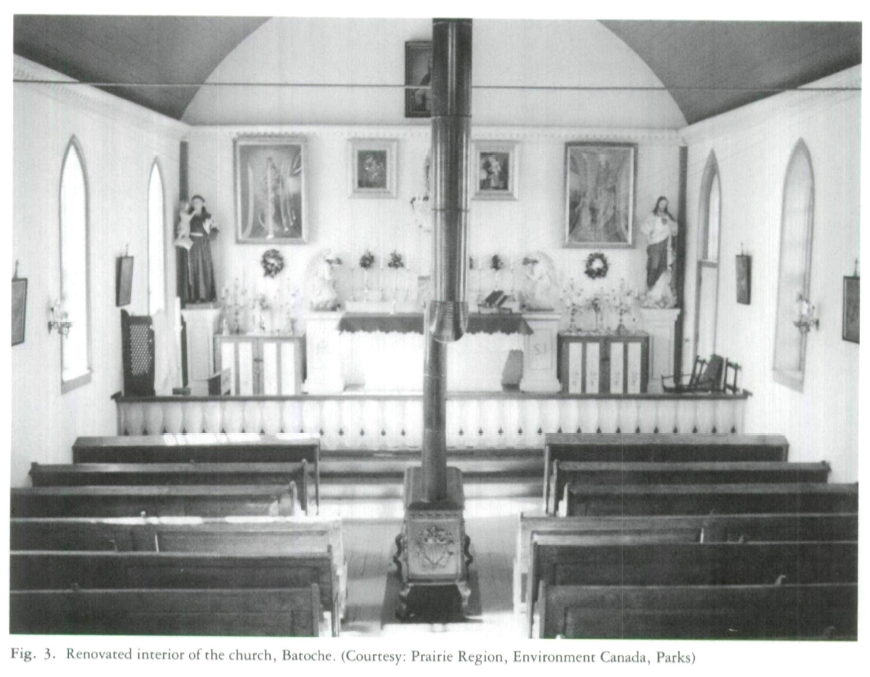

10 Exiting from the exhibit area, the visitor is directed towards the church and rectory, which are nicely framed in the windows of the visitor centre. These structures are all that remain of the Oblate Mission of Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue (established 1881), and although they figured in the rebellion (the church as headquarters for Riel's provisional government, the rectory as a hospital), they have been carefully restored to the 1896-97 period. The church has been returned to its former simplicity, while the rectory now features a period living area on the main floor and the private rooms of Father Moulin and a post office on the second. In each structure, there is a costumed guide who provides a brief, somewhat amateurish presentation in both official languages about the architectural features of the buildings (Red River square-timber style) and the people associated with them.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 211 From the mission ridge area, paths lead in two directions. Heading northwest, the visitor can view Métis rifle pits and the traditional river lot system of land holding before reaching the former site of Batoche and one of the few remaining portions of the Carlton Trail. According to the 1982 Management Plan, the east village is scheduled for major development during the project's second phase (1986-91). For the time being, the visitor can see the foundations of several former structures, as well as a number of period photographs of the village.

12 Proceeding in the opposite direction from Mission Ridge, the visitor can follow the old Humboldt, or St-Laurent, Trail (as it was known in the area) that the Canadian forces used to advance on Batoche. About a kilometre south, it is still possible to see surviving remnants of Middleton's zareba and rifle pits; again, these features are accompanied by contemporary photographs of the fighting and brief explanatory notes.

13 The opportunity to wander freely about the site is one of the most enjoyable aspects of the Batoche redevelopment. It is only by roaming the rolling prairie parkland that the visitor can appreciate how the two sides faced one another during the rebellion. To facilitate this experience, Parks Canada has undertaken considerable landscape restoration. It has also prepared an attractive brochure with a map and translucent overlays that enable the visitor to follow the course of the fighting. It would have been helpful, however, if the names of the actual trails were marked in some unobtrusive manner.

14 Currently, most visitors to Batoche tour the visitor centre and the restored church and rectory; only an adventuresome few make it down to the village or back towards Middleton's zareba. Most visitors simply do not expect to find so much. Many are also discouraged by the considerable amount of walking involved; some form of period transportation would improve the situation. If phase two of the management plan proceeds as outlined, perhaps visitors will come to take full advantage of the park and get some sense of what it was like during the late, cold spring of 1885.

Superintendent's Statement

15 Batoche National Historic Park has undergone extensive changes during the Phase Ⅰ level of development. A visit to the park and its new facilities and services is an invaluable learning experience in the comprehension of our heritage and a rare opportunity for the visitor to witness first hand an important segment of our Western Canadian history.

16 The Parks' Management Plan was prepared between 1978 and 1981 and involved an extensive public participation program with particular involvement from the Association of Metis and Non-Status Indians (AMNSIS).

17 Phase I of the Management Plan was initiated to preserve and protect the heritage resources of Batoche and to interpret the park's two main themes, the Métis culture and society of the South Saskatchewan River area (1860-1910) and the events of the 1885 Northwest Rebellion.

18 The physical development occurred from 1981 to 1986 at a cost of $7 million. Parks Canada consulted and involved AMNSIS in all aspects of the Phase I development.

19 This major development features a new Visitor Reception Centre, the restoration and furnishing of the historic Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue church and rectory to their 1897 functional appearance, interpretive exhibits throughout the park, relocation of provincial Highway 225 from the middle of the historic area under a cost sharing agreement with the province, road access to the East Village and removal of modern buildings and services from the historic area.

20 The new visitor centre building is an impressive but functional structure with a high-tech interior and exterior design. This style differs greatly from the usual muted Parks Canada architectural motif. The corrugated natural aluminum siding combined with the bright chrome-finish trim and the bottle-green glass of the Grand Passage make a strong statement, yet the building is nestled in a low area where it does not dominate the landscape. The contemporary assets are thereby readily distinguished from the historic.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 321 From within the visitor centre one is always in visual contact with the historic landscape and surroundings and as the visitor walks down the long Grand Passage the visual emphasis is on the historic Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue church and rectory neatly framed within the glass peak of the diamond end-wall.

22 The visitor centre provides many services. An 80-seat multimedia theatre houses the impressive and highly sophisticated 45-minute 18-projector Batoche audio-visual presentation. This program combines slides, theatrical lighting techniques, mannequins depicting the main personnages of Batoche history in various historical scenes, and a heart-rending narrative with an original musical score designed specially to draw one back to the mid-nineteenth century and let one experience first hand the history and culture of the Métis as well as the many events that led to and continued after the rebellion in 1885.

23 The exhibit hall depicts the site's two major themes and houses numerous artifacts which so aptly tell the history of Batoche. The lifelike dioramas, period pictures and paintings, an actual-size Métis rifle pit, the uniformed military mannequins and devices, all provide an invaluable testimony of this heritage.

24 Located in the visitor centre are a craft/souvenir outlet with local Métis handicraft and a food concession offering, among other fare, traditional Métis foods such as bannock and tourtière. A picnic area is located adjacent to t he-visitor centre.

25 The visitor centre is entirely accessible to the handicapped and the park where the terrain permits.

26 The historic Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue church and rectory have been completely restored to 1897 and house many original artifacts of the period. Costumed interpreters are present at both these locations to provide important details concerning the structures, their use, the people that occupied and used them, and the role they played in the history and the story of Batoche.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 427 Interpretive ground signage is located throughout the park at other key locations, such as the East Village, the zareba, the military and Métis rifle pits, the Caron farmhouse and the ferry crossing, to provide additional information on the park's history, its main features and characteristics.

28 Employment of the Mens people at Batoche National Historic Park is a high priority. To dare, there is good representation and efforts at the park level have been made to assist them in obtaining employment.

29 The first season of operation was a success and saw over 38,000 visitors come to the park and enjoy its new facilities and activities. Visitors expressed satisfaction with the restoration of the historic buildings, the new visitor facilities and services and, in particular, with the audio-visual presentation which was often favourably compared to those programs presented at Expo 86. The park's staff appreciate their new office space and have adapted well to the new systems and procedures. We look forward to trying out new ideas and improving our 1987 visitor season program now that Phase I development is complete.