Reviews / Comptes rendus

Newfoundland Museum, "For King and Country: Newfoundland and the Fighting Services, 1689-1945"

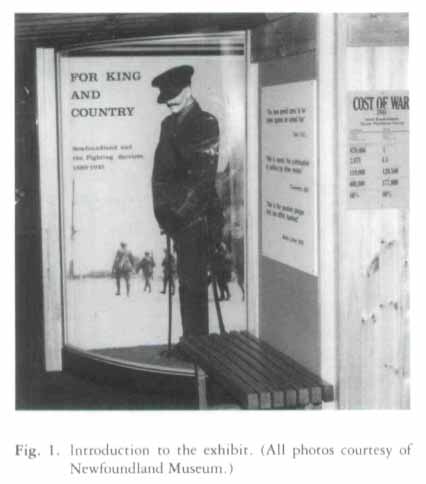

1 A mannequin, dressed in the uniform of an officer of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment during the First World War, head bowed, arms resting on a sword, stands as a mute memorial to Newfoundland's sacrifice for King and Country over the course of nearly three centuries. Beside this display on an adjoining wall are three pronouncements on the nature of war:

The juxtapositioning is intentional. The Newfoundland Museum seeks to recount Newfoundland's and Newfoundlanders' involvement in war and with the fighting services in the period from 1689 to 1945 while underscoring the terrible cost of that involvement to the island and its people. Beside each of the major displays, the "Cost of War" reminds the viewer that patriotism, however commendable and however justified by the circumstances, can be a heavy burden. Witness the cost of the First World War to Newfoundland, where on 1 July 1916 at Beaumont Hamel the Newfoundland Regiment was nearly wiped out, suffering 710 casualties out of a total force of 770. To this day, 1 July is a day of mourning in Newfoundland. Of the first contingent, the famous Blue Puttees, 445 were killed or wounded out of the 537 sent overseas. There was not a street in St. John's that escaped the loss of a family member or friend in that war.

Display large image of Figure 1

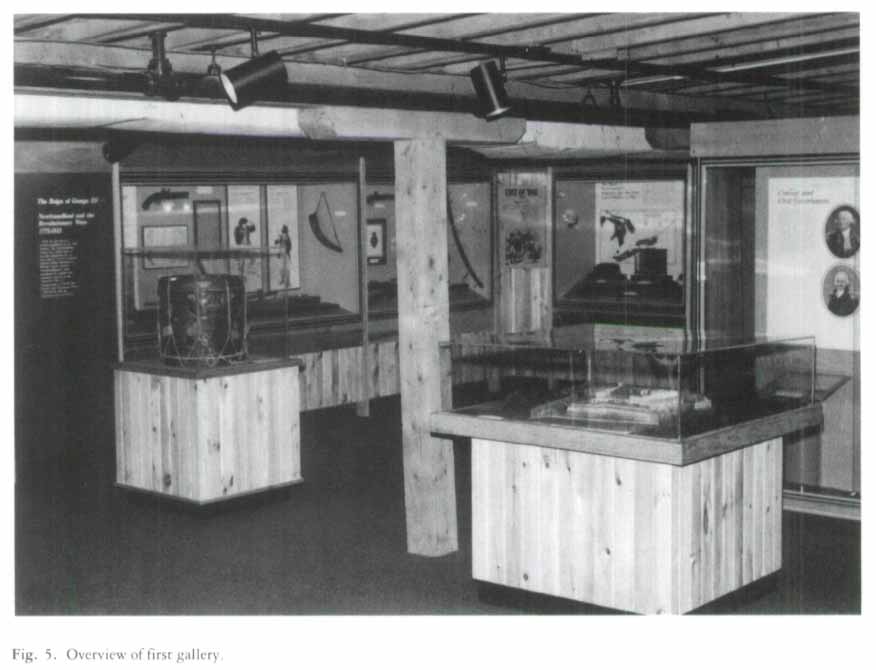

Display large image of Figure 12 The military museum occupies the top floor of the Murray Premises, a restored warehouse in downtown St. John's. The location is a good one, close to the waterfront and within the area popular with tourists. The building itself is very attractive with a warm wood interior and on the top floor, exposed beams. The setting seems ideal, but for the display of museum artifacts it poses a challenge. The top floor is actually a loft, partly exposed to the third floor below. The ceiling is low. Upright supports and cross beams make the small space even smaller. That the museum stall members have been able to use this limited space in such an imaginative way is a testimony to their skills and inventiveness.

3 A modular format for the displays helps alleviate the problems of space and building design, and allows for a pleasing arrangement of unified historical material. The museum has two main galleries. The first relates to Newfoundland's military and naval history up to the First World War. It begins with a display of items from the opening years of the long contest between Britain and France (1689-1762) and ends with the volunteer movements of the end of the century. The artifacts on display in this area are well selected from the limited number available but are representative of the weaponry, uniforms and accoutrements of the three hundred years covered. The displays are interesting, colourful and with a nicely balanced arrangement that does not overwhelm the viewer with too much detail. The illustrations and commentaries are well done with sufficient explanatory detail to complement the material on view. Each display has its own integrity, based on a selected theme or time period, an arrangement followed successfully throughout the museum.

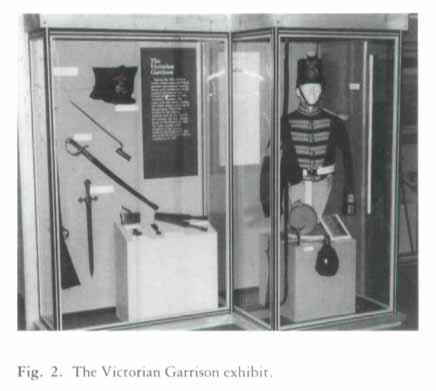

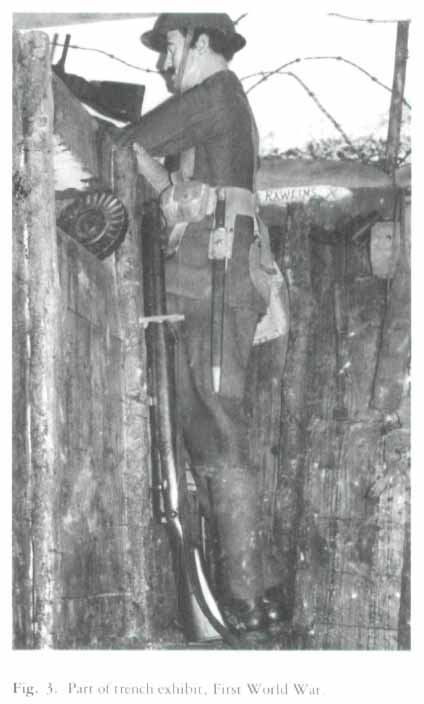

4 On entering the first gallery, the visitor is made aware of the strategic importance of the island during the long years of Anglo-French rivalry. It was here, for example, that the first battle in the Seven Years' War in America was fought. Few might realize the significance of Newfoundland's involvement in the American wars, and especially during the War of 1812. There are other displays of interest. Newfoundland's Victorian Garrison was recruited for the most part locally, a practice not found elsewhere in British North America at this time. The cadet corps founded here at the end of the last century, which were later to be so important to Newfoundland's war effort in 1914, were entirely sectarian in origin and sponsorship.

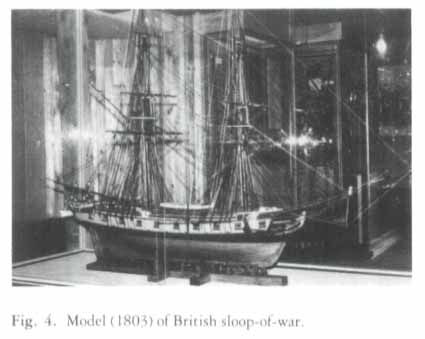

5 In the centre of the first gallery are the naval displays from the late seventeenth to the early twentieth century. Here the curatorial staff had less local material to use in the displays but managed to find enough representative material from the period to serve their purposes. An excellent dockyard model of the kind of ship that plied the waters off Newfoundland, guarding the sea lanes and convoy routes at the beginning of the last century, is the focal point of the naval display (see fig. 4). Other items, principally uniforms from the last century, remind the viewer that in the years before representative government was introduced to Newfoundland the Royal Navy was responsible not only for the protection of the fishing fleet but also for civil government and the administration of justice. Once a civil administration was in place in the 1820s and after the introduction of steam reduced the need to maintain isolated squadrons in distant waters, the naval presence in Newfoundland waters declined, not to be revived until the heyday of the convoys during the Second World War.

6 On the dividing wall between the two galleries there is an illustration of fortress construction, complemented by a separate display of a model of the French fort at Placental. The limitations of space apparently did not permit a more effective juxtapositioning of the two. If at some point the museum is able to build a model of the first English tort in Newfoundland, Fort William, it should be displayed more effectively. Elsewhere on the wall are useful drawings of weapons technology in the nineteenth century illustrating the importance of major developments in firepower and weaponry in increasing the destructive potential of warfare.

7 The second gallery covers the twentieth-century wars and follows logically out of the military displays in the first gallery. The widening scale of war, its incredible destructiveness, its broader impact on the lives of Newfoundlanders are all underscored in this section of the museum. For the twentieth-century period, the wealth of resource material available allows for a more interpretative presentation of Newfoundlanders at war. For example, at the entrance to this gallery, set against a backdrop of the Somme battleground, is a cutaway of a First World War trench. A lone soldier of the Newfoundland Regiment stands guard against an invisible enemy while in an adjoining bunker an officer, momentarily diverted from the business of war, cleans his pistol. The art of the museum technical staff in capturing some of the realism of life in the trench has been expertly put to use in this display. For Newfoundlanders it is a reminder of the tremendous sacrifice made by a young generation on the fateful battlefields of Gallipoli, the Somme, Beaumont Hamel and Bailleul. Elsewhere, the displays cover other aspects of the war - recruitment and mobilization, the patriotic effort at home, chemical warfare, in which a Newfoundland doctor was to play a prominent role in devising protective masks, and the war in the air. Because of its lasting significance to Newfoundland, Beaumont Hamel is appropriately given special attention. An open map of the battleground with faintly pencilled lines indicates the impossible objective of the attack. A letter from a survivor describes in disbelieving detail the dreadful carnage suffered by his comrades in the regiment. To the side of the display, the toll of battle underscores the terrible cost of Beaumont Hamel to Newfoundland. For Newfoundland, the First World War represents the ultimate sacrifice for King and Country.

8 Newfoundland's involvement in the Second World War is radically different in kind and in scale from the First World War. There is no repetition of the large drafts of manpower sent off to distant theatres, nor of the terrifying losses suffered by native sons. Newfoundland's contribution was important but more diverse. Over 4500 Newfoundlanders served in the senior service, 2400 in the artillery and other land units, and over 700 in the air force in the European and African theatres. A large contingent was involved in local defence as the Newfoundland Home Defence Regiment. The real prominence of Newfoundland during the war lay in the importance of St. John's, Newfy John as it was affectionately called, to the North Atlantic convoys. The museum has done well in dealing with so broad a subject in the minimum amount of space available. The displays for this period consist principally of uniforms, a small collection of mementoes from the war years, and a mock-up of a communications centre complete with signaller. This latter display seems less representative of Newfoundland participation in the war than does the excellent mock-up of the First World War trench. Perhaps more effort might have been made to emphasize the importance of Newfoundland to the North Atlantic convoys. There should also have been some reminder of the role of Gander and Botwood as air bases during the war. But these are only minor points in what is generally an effective representation of Newfoundland's involvement in the Second World War. This section of the gallery ends with a large print of the devastation of Hiroshima, alongside which are repeated the opening statements on war, the original order altered to place Luther's quotation at the top. At first glance, neither the bombing of Hiroshima nor Luther's condemnation of war seem to have much to do with Newfoundland's military heritage. But on reflection, the subtlety becomes clearer. Warfare in this century is no longer the affair of soldiers, sailors and airmen confronting one another in distant and isolated campaigns. We have entered the era of total war when the potential for destruction has become global in scale. In any future war, civilians and soldiers will be placed on a common battleground.

9 Dr. Bernard Ransom and his staff are to be congratulated on an imaginative, interesting and provocative presentation of Newfoundland's military history over the past three hundred years.

Curatorial Statement

10 The basis of the Newfoundland Museum's military collection was assembled during the early 1960s to furnish the permanent exhibits of a then independent Newfoundland Naval and Military Museum. These exhibits remained virtually unchanged until their closure for redevelopment by the provincial institution in 1980. Modest in scale, this original collection, especially in the weaponry and accoutrements areas, relied heavily upon archetypal British and French eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artifacts. There were, additionally, a number of items of equipment, uniform and weaponry, together with some documents, of direct Newfoundland provenance ranging in period from the late eighteenth century to 1914-18. A renewed and urgent collections drive was mounted in 1981 in preparation for the redeveloped War Exhibit: priorities focused on artifacts of local provenance for all periods, together with items representative of the land, sea and air arms of the services for the two world wars of the present century. The generally satisfying results of this major collecting effort enabled staff to attempt a more sustained and thematic treatment throughout the gallery, especially in the First and Second World War exhibits.

11 In its pedagogical arrangement, the exhibit is primarily historical. Social, political, technical and other themes are addressed entirely within the context of a basic division into four historical periods:

- 1689-1816: The almost continuous warfare between the British empire and its French and American opponents

- The nineteenth century: The peacetime Victorian Garrison

- The Great War: 1914-1918

- The Second World War: 1939-1945

Within this periodization, a balance is attempted between treatment of the technological history of warfare and some narrative description of the war-related involvements of Newfoundland and its people. Museum exhibits are, unavoidably perhaps, concerned with the concrete paraphernalia of technique — and so it seemed imperative to devote substantial space to matters of weapons development, tactical and logistic considerations and the whole issue of technical determinants of military operations in each period. This technological element is accompanied generally by two interrelated narrative themes: the impact of war and of the presence of armed forces on the Newfoundland community (especially in its nascent stage in the eighteenth century), and the contributions made by that Newfoundland community to successive British Imperial and Commonwealth war efforts during the mid-eighteenth to the mid-twentieth century.

12 The technological component of the first period centres on a model/graphic composite interpretation of the "Art of Fortification" and an original (1803) dockyard model of a British sloop-of-war, the workhorse of North Atlantic convoy and Newfoundland trade protection in the days of fighting sail. The fortification display emphasizes that late seventeenth-century state-of-the-art "geometric" fortification was first applied by both French and British military engineers in the New World in Newfoundland locations. In an age when military operations largely revolved around siege crafts, the narrative displays indicate something of the successes and failures of local sieges during King William's, Queen Anne's and the Seven Years' wars. Later narrative displays indicate the origin of Newfoundland's regimental tradition (albeit discontinuous, the oldest in the Canadian Service), stressing the importance of the Newfoundland contribution to the defence of the Canadas during the attempts of American invasion and annexation (1775 and 1812). Within the naval exhibit, some attention is given to the crucial nature of sea power in the preservation of the Newfoundland colony; also indicated is something of the problematic experience of the local settled community's growth under the jurisdiction of vice-admiralty law.

13 The Victorian section contains some important rare artifacts dating from the early nineteenth-century local regular units, as well as other items from their auxiliary support, the recreational volunteer corps. A display on the turn-of-the-century local naval reserve force (one of the very few such units at the time outside the British Isles) indicates some of the features of naval training and preparedness required in an age of transition from sailing to sophisticated steam-powered warships. Technologically, a graphic display highlights the nineteenth century revolution in firepower for both small and large calibre weapons. From flintlock, through percussion, to cartridge fire, the development is traced from black-powder smooth-bore weapons to the smokeless magazine rifle, quick-firing artillery and the machine gun. In preparation for the following Great War exhibit, it is emphasized that despite such changes tactical thinking remained largely "Napoleonic."

14 A major diorama, a trench/dugout section, represents a main technological feature of the Great War exhibit. The scenario is as complete as the resources of the collection would allow, containing two fully dressed and equipped mannequins in conditions of theatrical desolation and squalor. An attached description of trench warfare invites visitors to make some comparisons between this early twentieth-century "field-fortification" fighting and its precursor, the siege craft of the late seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries. Other technology exhibits in this section feature air power and chemical warfare. (Allied countermeasures in the latter area owed much to a particularly outstanding Newfoundland contribution.) Narrative treatment of Great War involvement centres upon the record of the 1st (Royal) Newfoundland Regiment, which fought with British regulars from Gallipoli to the Armistice, never fielded a conscript, and in 1917 was awarded the designation "Royal..." in the field (only the third time such a conferral was made in wartime in the entire history of the British army).

15 The Second World War displays focus on specialist participation/contribution, logistical concerns and total mobilization. Mannequin presentations represent naval, air and land services (women's services included) and also the considerable home defence air raid precautions effort (an undertaking which gave St. John's more the atmosphere of a wartime British city than a North American one). A small naval display on the importance of the Newfoundland escort base for North Atlantic convoy routes (including some captured U-boat items) indicates how, in 1940, the island regained some of its earlier significance in terms of ocean strategy and logistics. Perhaps the most elaborate element in this section is the artillery command post mini-diorama featuring a comprehensive range of communications and plotting equipment used by this specialized corps. Two Newfoundland gunner regiments were raised for active service overseas in 1939-40 (an attempt to reduce the disastrous infantry casualties suffered during the Great War); this composite display tells something of their joint service in Britain, in the North American and Italian campaigns and in Northern Europe after D-Day.

16 Additional to these pedagogical undertakings of the kind expected of a public museum, it was decided to include at appropriate points an avowedly devotional flavour more typical of the regimental/corps type of museum. This decision was based on the conviction that matters involving serious loss or sacrifice in war are not adequately handled by a merely analytical or objective approach. Objectivity, it was feared, if left unrelieved by some counterbalancing commemorative tone, might too rapidly lead to uninformative abstraction. There was no intention in this regard to preclude or obscure the possibilities of critical response to the general issues of war and warfare; rather it was hoped that inclusion of commemorative/meditative features might encourage visitors toward a critical reflection of a more affective, less abstract nature. The image on the introductory panel to the Second World War section of SS troops at a Nuremberg rally in the late 1930s is of this type: although not of direct relevance to the adjacent storyline, it is intended to indicate something of the rationale behind the decision to make war. The most salient example of this element is the "title" or frontispiece to the gallery itself- a mannequin dressed as a Newfoundland battalion officer of 1914-18 and arranged, with dress sword, in the mourning "reversed-arms" posture. This figure is further seen, from a slightly oblique angle, by viewers of the Beaumont Hamel display within the Great War section. The virtual annihilation of the Newfoundland battalion at Beaumont Hamel on the first day of the Sommer Offensive, 1 July 1916, is of tremendous importance locally, hence the decision to treat the event in the display in a devotionally appropriate and meaningful way. July 1, "Memorial Day," remains a day of commemoration in Newfoundland hardly less significant than November 11.

17 The gallery had always been intended as something more than a "military history" exhibit; it is indeed a "war exhibit" concerned with the broader cultural and historical perspectives within which war is prosecuted. Moreover, any "war exhibit" produced in the mid-1980s by a public institution necessarily must take some account of contemporary opinion on the general issues. In this regard, the museum administration was insistent that the exhibit should in no way appear to be "glorifying" the subject. Whether or not that particular concern was ever a real likelihood, the question of the "responsibility" of the exhibit in this respect remained. A historical perspective which gave more depth of meaning for the entire issue than straightforward pro- or anti-war statements of the contemporary type was sought in reference to three principles:

- That war — throughout the history of our civilization — has always been justified by appeal to the highest spiritual authority.

- That war — especially as it occurs in our modern history — is normally a policy expression of legitimate state authority.

- That war — with increasing severity — is a monumental waste of human and material resources.

These three principles, the metaphysical, the analytical and the humanistic, appeared to provide a good keynote for a rational and rounded historical overview. To some extent, the humanistic perspective had been footnoted throughout the gallery by a "Cost of War" graphic feature in each section which provided a tally of sorts for Newfoundland-land losses in each context (human and economic). Expression of the three key principles was found in the following quotations:

- Metaphysical: "The laws permit arms to be taken against an armed foe" (Ovid)

- Analytical: "War is merely the continuation of politics by other means" (Clausewitz)

- Humanistic: "War is the greatest plague that can afflict mankind" (Luther)

At the entrance to the gallery, these quotations were mounted, in the above order, immediately adjacent to the mourning/meditative officer figure of the frontispiece. They were mounted again at the end of the exhibit beneath a large photo-mural of the devastated landscape of Hiroshima in 1945; but this second time in reverse order.

18 Hopefully, the exhibit does some justice to the experience of those in and from Newfoundland who participated in and suffered through the wars of their generations. Hopefully it may also provide a historical perspective for the average museum-goer for whom thoughts on the issue are dominated by the "unthinkable" nuclear nightmare. "For King & Country" deals with a period, mid-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth century, when war was a routine and feasible (if costly) instrument of state policy. The exhibit's final note is a suggestion that the instrument as traditionally used is now obsolescent and self-defeating - a challenge to find wider loyalties than those so dearly served throughout our past.