Articles

Loyalist Style and the Culture of the Atlantic Seaboard

Résumé

Les meubles et les articles décoratifs que les membres de l'élite loyaliste amenèrent en exil ont acquis une importance particulière dans les nouvelles collectivités de l'Amérique du Nord britannique. Le présent document vise à mieux définir le rôle culturel de certains articles qui appartenaient aux dirigeants loyalistes du Nouveau-Brunswick. De cet examen ressortent cinq points à retenir. Premièrement, même si ces dirigeants venaient de différents endroits du littoral atlantique, leurs biens les plus précieux présentent des caractéristiques communes, notamment une préférence marquée pour les surfaces polies et le style rococo. Deuxièmement, ces goûts bien arrêtés montrent que les loyalistes ont participé à la profonde transformation culturelle survenue aux États-Unis au milieu du XVIIIe siècle, quand la société du littoral a commencé d'imiter la mode britannique dans tous les aspects de sa vie, depuis le culte religieux jusqu'aux meubles. Troisièmement, l'anglicisation de l'élite du littoral est à l'origine du style géorgien dans l'architecture et l'art américains et a contribué à une stratification accrue de la société coloniale américaine. Quatrièmement, le style de vie luxueux de cette élite est devenu un problème politique brûlant pendant la guerre de l'Indépendance, ce qui a amené de nombreux représentants de la première élite coloniale à épouser la cause loyaliste et finalement à devoir s'exiler. Cinquièmement, la place privilégiée que les dirigeants loyalistes du Nouveau-Brunswick et leurs héritiers accordaient aux objets étudiés ici doit être interprétée comme la preuve symbolique de leur détermination à transplanter l'aristocratie coloniale dans leur nouveau milieu.

Abstract

The furniture and decorative items that the Loyalist elite carried with them into exile acquired special significance in the new communities of British North America. This paper looks at a selection of artifacts owned by the Loyalist leaders of New Brunswick in order to define their cultural role more precisely. Five points arise from this examination. First, although these elite leaders came from diverse points along the Atlantic seaboard, their most cherished material possessions exhibit common stylistic characteristics, particularly the preference for highly polished surfaces and rococo design. Second, this expression of taste reflects Loyalist participation in the profound cultural transformation of mid-eighteenth-century America, whereby seaboard society began emulating English metropolitan fashions in every aspect of their lives from religious worship to furniture design. Third, this "Anglicization" of the seaboard elite both inspired the brilliant Georgian period in American art and architecture and led to increased social stratification in American colonial society. Fourth, the luxurious life-style of the seaboard elite became a searing political issue in the American Revolution, with the result that many members of the original colonial elite adhered to the Loyalist cause and eventually had to go into exile. The fifth and final point concludes that the hallowed place given to these artifacts by the Loyalist leaders of New Brunswick and their heirs must be interpreted as symbolic evidence of their determination to reproduce a colonial aristocracy in their new homes.

1 Loyalist furnishings played a social role in early Maritime Canada that is typically reserved for architecture and the fine arts in older, more complex societies. Because they had to re-establish their lives in a wilderness after a long war and forced exile, even the most prosperous Loyalists could not reproduce the elaborate household and social rituals that had defined their status in mid-eighteenth-century America. Yet these same circumstances made the items that they could transport to their new homes especially significant. Fine furniture in particular conferred social power in the new settlements; so too did military regalia, worked silver, imported wallpaper, and fashionable dress. In short, any decorative item that had elite connotations and could be brought overland or by sea to Nova Scotia or New Brunswick took on added significance in the Loyalists' new homes.

2 These new possessions of the Loyalist elite have been featured prominently in the museum exhibits and decorative art publications of the last two decades. The illustrated works of Charles Foss and Donald Webster have been particularly helpful in establishing much firmer criteria for identifying Loyalist artifacts and grouping them regionally.1 The main thrust of these exhibits and publications to date has centered around the documentation and stylistic definition of individual objects, recording their date, maker, place of fabrication, and general aesthetic characteristics.

3 Fundamental as this information is, it must be complemented by inquiries into the cultural context of these objects. We cannot begin to understand the contribution these objects made to Canadian culture until we ascertain the particular set of historical meanings the Loyalist elite invested in these objects. E.H. Gombrich cautions, "the historian does well to remember that his values are not necessarily those of the past."2 For example, if one speaks contemporaneously, from the viewpoint of the Loyalists who brought these elite objects to the Maritimes, displayed them in their homes, and passed them on so purposefully in their wills to their heirs, it quickly becomes apparent that the date of fabrication, the maker, and his locale were far less important than the expressive style of the object itself — the potential for social display permitted by the nature of the materials, the degree of craftsmanship, and the actual contours of the piece.

4 In this brief paper I propose to discuss a range of objects owned by the Loyalist elite of New Brunswick and to comment on their social significance by drawing on the recent findings of American and Canadian cultural historians working in the eighteenth-century period. It is my hope that, by integrating the documentary work of Canadian art historians with the broader explorations of the cultural historians, we can begin to define the social role of these elite objects and their powerful normative impact on early Canadian culture.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 I must begin by placing the term elite — a gift of modern sociology — in its proper historical context. The group of dissenters, adventurers, and emigrant poor who founded the American colonies shared the same beliefs in the social and political hierarchy as their counterparts in England.

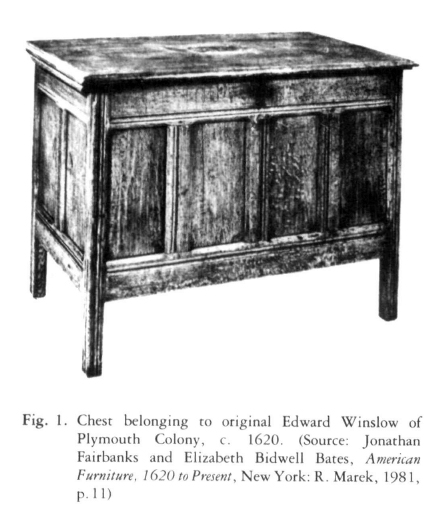

6 Although the Puritan fathers disagreed profoundly with the Stuart monarchy on the appropriate forms of aesthetic expression, their goal was to push the clock back rather than forward, to restore the traditional Tudor consensus on the importance of social hierarchy and on the need to express public authority in tangible, visible symbols. Puritan doctrine expected leaders on both sides of the Atlantic to live in homes, dress in apparel, and sit in chairs that manifested their authority. In New England, the preferred expressive form was, of course, the famous "plain style" illustrated here by the sturdy chest (fig. 1) of Gov. Edward Winslow.3 The firm lines and red oak of this piece encapsulate the Mayflower generation's notions of patriarchal authority. The persistence of these traditional notions, within the American colonies can be seen in the birch chest of Moses Pickard (fig. 2), the leader of the Puritan settlement in Maugerville, New Brunswick, in the 1760s. Although separated by 150 years, both pieces exhibit the emphasis on simplicity, rationality, and familiar but finely crafted materials, which was the hallmark of the Puritan leadership.4

Display large image of Figure 2

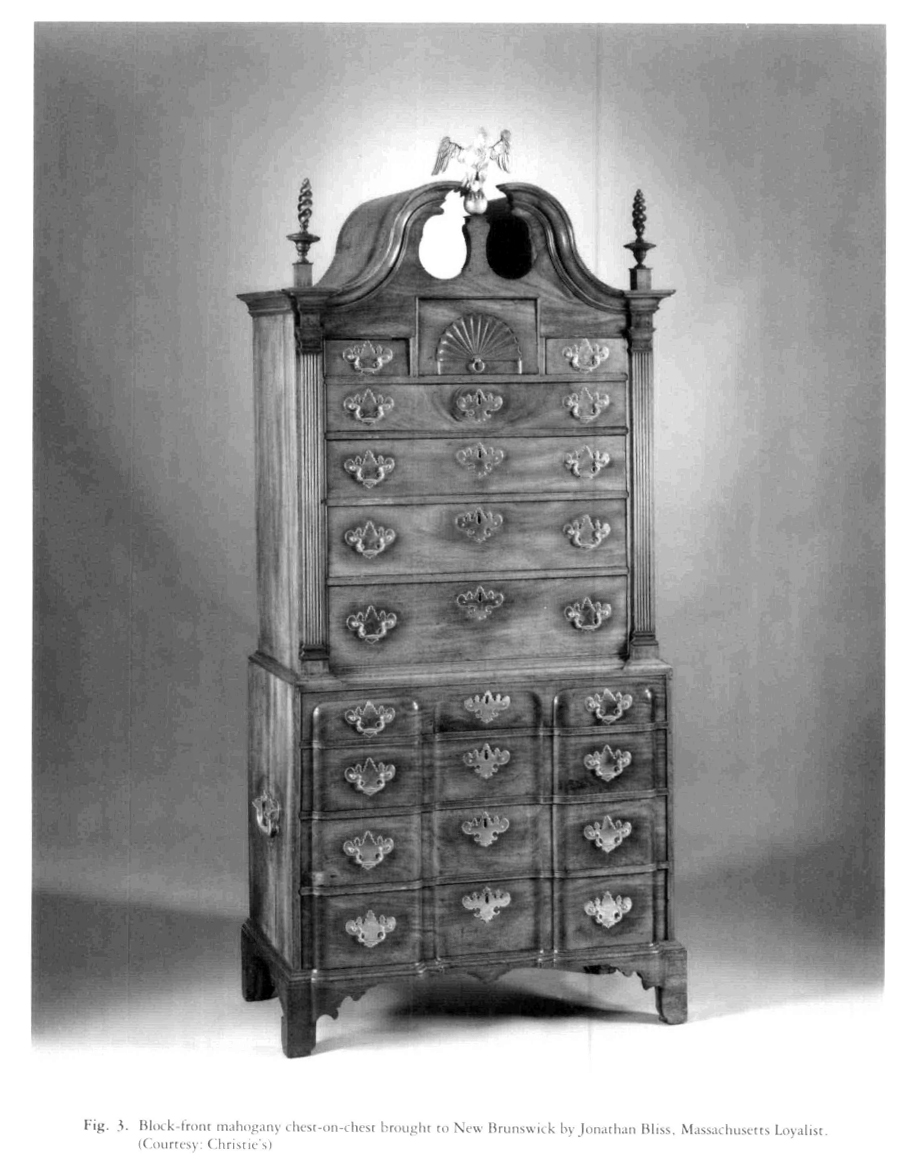

Display large image of Figure 27 The move from these symbols of traditional authority to the new forms adopted by the seaboard elite in the eighteenth century is remarkable. A prime example is the block-front mahogany chest-on-chest (fig. 3) brought to New Brunswick by the Loyalist leader Jonathan Bliss. A native of Massachusetts, a graduate of Harvard, a protégé of Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, Bliss was a privileged member of the Massachusetts governing elite in the 1760s.5 His ownership of this elegant chest provides dramatic evidence of a profound shift in values within the colonial elite — away from the plain style of the Puritan founders in favour of the new rococo spirit of commercial England.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 38 This cultural shift provides the essential background for understanding the Loyalist phenomenon. Suddenly in the mid-eighteenth century, the upper portions of the colonial governing circles abandoned their Puritan ties and embraced the luxury, the pomp, and the rituals of Georgian England. They joined the Anglican Church, sent their children to British schools, ordered the pattern books of Thomas Chippendale hot off the press, and generally mimicked the forms of pleasure and spiritual expression valued in the metropolis.6 The dramatic, escalating nature of this colonial fascination with the products and styles of the Mother Country can be seen in the rise in American consumption of English goods, as reported by Bernard Bailyn: "English exports to North America increased almost eightfold from 1700 to 1773; between 1750 and 1773 it rose 120 percent; and in the five years from 1768 to 1772 it rose 43 percent."7

9 The conversion to high English cultural style, the "Anglicization" of the American colonial elite, as it is called, also had a profound effect on colonial craftsmen. It inspired a gifted series of cabinetmakers, first in Newport and then in all the urban centres.8 It produced a notable, extravagant period of domestic architecture all along the seaboard.9 For example, the third Edward Winslow felt compelled to build a mansion across from Plymouth Rock in 1750, an act of grandeur totally out of keeping with his ancestor's values and ruinous to his own family's finances.10 This cultural flowering reached its ultimate expression in the paintings of John Singleton Copley, court painter to the seaboard elite, who captured in flattering, sumptuous scenes their love of fine materials, glittering surfaces, and comfort.11

10 It was a brilliant moment in American cultural life, but it was accessible only to a favoured few. Those left out resented the exclusiveness of these new cultural forms and the implied rejection of the Puritan inheritance. For John Adams, polite society and the new rococo style posed an insidious threat to the moral character of Americans:

11 Popular anger against this new social order focused on the material expressions of elite culture.13 On the night of 25 August 1765 a Boston mob protested against the Stamp Act by attacking the mansion of Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson. The systematic destruction of the house lasted until dawn: clothing, plate, paintings, manuscripts, even money were first destroyed. Then the looters proceeded to dismantle the house, axing in doors, ripping off wainscotting and hangings, splintering furniture, smashing doors, and tearing up the formal gardens. So great was their determination to lay waste this symbol of elite culture that they "worked for three hours at the cupola before they could get it down."14 In the next decade the conflict between these two intensely held value systems broke into open warfare. Hutchinson, Copley, and many other elite leaders left America forever. The Loyalist cause was born.

12 This brief review of the cultural origins of the objects that the Loyalists brought to Canada provides a glimpse of their talismanic powers — to both their owners and their opponents.15 The examples used thus far have been drawn from Massachusetts, the original storm centre of the Revolution. By the end of the war, however, all thirteen colonies were involved, and the New Brunswick collections include objects from many points along the Atlantic seaboard. Despite local variations, the objects are stylistically united by their emphasis on sinuous line and glittering surface.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

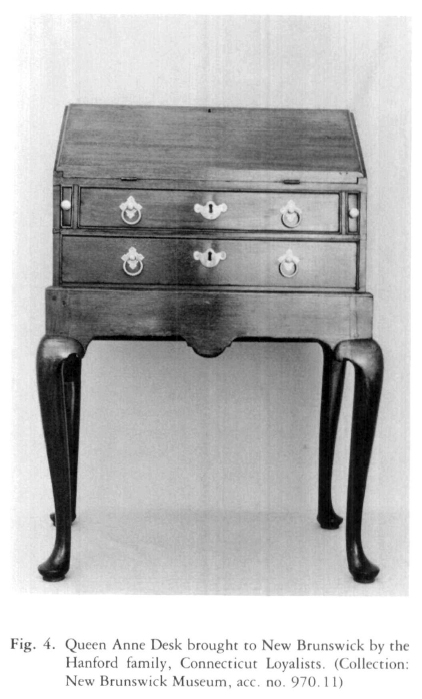

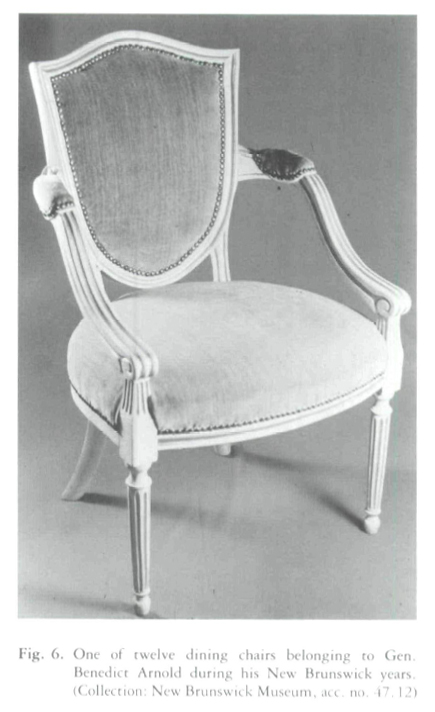

Display large image of Figure 513 A particularly graceful example of Loyalist taste is the small desk brought by Thomas Hanford, a Connecticut merchant, to New Brunswick (fig. 4). There are chairs from almost every province. The Hallett chair from New York (fig. 5) illustrates the Loyalist delight in intricate carving, while the twelve chairs that Benedict Arnold brought from Philadelphia (fig. 6) stress elegance of line. The chronological range within Loyalist style can be seen in two examples from northern New England: the tallboy that Dr. John Caleff brought from Maine is assigned to the year 1740 by Charles Foss, while the corner chair that the Winslow family purchased in New Brunswick was probably made after 1800.16 The Loyalists' abiding commitment to family life is evocatively expressed in the cradles, personal portraits, and samplers that decorated their homes.17

14 A preference for mahogany surfaces is evident throughout Loyalist furniture. Patrick Campbell, the outspoken Scottish traveller to New Brunswick, deplored this dependence on imported materials and urged New Brunswickers to cultivate their own beautiful native woods.18 Campbell was right, of course, but the earnest Highland soldier simply could not understand the historical connotations that mahogany held for the Loyalist exiles.

Display large image of Figure 6

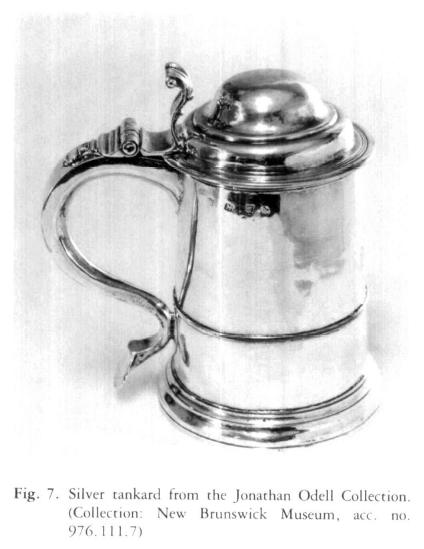

Display large image of Figure 615 Small silver objects were equally favoured, due to both their lustrous surface and their ease of transport. Among the many tankards, mugs, and serving pieces, the New Brunswick collections include some objects with personal connotations that permit a more intimate glimpse into elite values. Samuel Vernon of Newport, Rhode Island, made a crested tankard as a wedding present for Edward Winslow from his bride, Hannah Dyer. Jonathan Odell's tankard is equally grand (fig. 7) and reminds us of the many toasts and drinking songs that he composed as royal chaplain to the King's American Dragoons. There are doubtless similar stories, now lost to time, that explain the silver cow that was made in London in the 1760s and brought from Connecticut by the Hubbard family to New Brunswick, or the exceptionally dignified silver creamer (fig. 8) made by the silversmith Jeremiah Brundage in New York City and then carried by the craftsman himself to Saint John in 1785.

Display large image of Figure 7

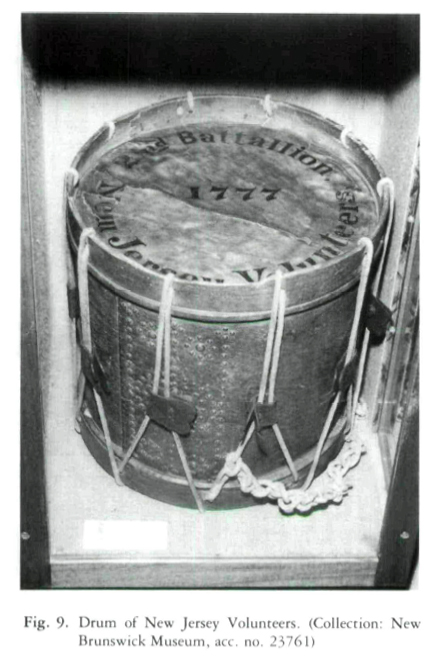

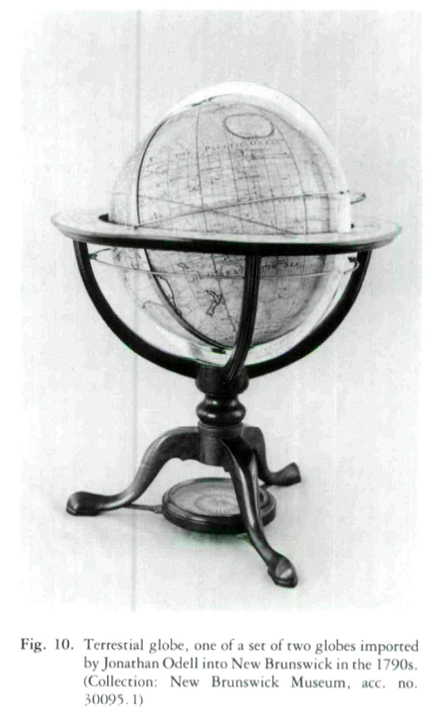

Display large image of Figure 716 Military mementoes — swords, rifles, pistols, uniforms, campaign gear — form a large component of the New Brunswick Loyalist collections and provide sharp counterpoint to the decorative items. Two of the most treasured pieces are the battle-scarred drum of the New Jersey Volunteers (fig. 9) and the swash-buckling portrait of Col. John Saunders of Virginia.19 Tokens of intellectual culture are surprisingly thin among the surviving Loyalist artifacts, given the high number of college graduates among the elite and their zealous efforts to establish a college, an endowed library, and even a theatre in New Brunswick. The only really impressive set of books and intellectual paraphernalia are contained in the Jonathan Odell Collection. His library of over 200 volumes includes works in several languages on an astonishing range of subjects, mute testimony to Odell's deep personal involvement in the English Enlightenment. It also includes his own Essay on Prosody, a 200-page study of English poetical rhythms, which Odell wrote during his New Brunswick years in a desperate and futile effort to stay in touch with the English world of letters. In addition to these literary items, the collection contains two magnificent "royal" globes, which Odell imported from England to launch the instructional program at the newly founded College of New Brunswick (fig. 10). In fact, the entire Odell Collection provides a haunting reminder of both the idealism and the frustration that accompanied the elite's efforts to re-establish, in wilderness conditions, their once-glorious cultural life.20

17 Perhaps the extent of the compromise the elite had to make with their environment is best illustrated by their houses, of which the Odell house in Fredericton and the Bliss house in Saint John are typical.21 The descent in both scale and design from the Georgian mansions of their earlier days is evident. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that inside these houses, powerful tokens of their commitment to superior style and craftsmanship occupied a place of prominence during the Loyalist period and for generations to come. The block-front chest-on-chest (fig. 3) that began this presentation was owned by Jonathan Bliss, Chief Justice of New Brunswick. At his death, it passed to his son William, who married the only daughter of Sampson S. Blowers, his father's old Harvard roommate and later the Loyalist Chief Justice of Nova Scotia. Young Bliss moved to Halifax, and was himself eventually appointed to the Nova Scotia Supreme Court. The "eagle chest" adorned Halifax society during his lifetime. It then passed to his eldest daughter, who married William Odell of Fredericton, and the chest came back to New Brunswick. Until the year 1939, when it finally went to a relative in England, the chest bobbed back and forth across the Bay of Fundy, decorating the social lives of the elites in both provincial capitals.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 918 The history of this piece is not exceptional. Fine furniture had a peculiar symbolic meaning for the original Loyalist generation, which their heirs have respected and carried on. For this cultural reason, it is simply not sufficient to lump Loyalist furnishings together with other eighteenth-century artifacts under a general "Georgian" rubric. Loyalist furnishings played a distinctive role in the history of the North America colonies: first as symbols of elite authority, then as victims of revolutionary attack, and finally as emblems of Loyalist sacrifice. Only by linking these objects with their historical circumstances can we begin to understand the messages embodied within Loyalist style — the specific attitudes towards aesthetics, history, and hierarchy that dominated the developing culture of English Canada.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10