Reviews / Comptes rendus

Royal Ontario Museum, "The Canadiana Gallery"

1 The new Canadiana Gallery at the Royal Ontario Museum is an introduction to the institution's existing Canadiana galleries in the Sigmund Samuel Canadiana Building located two blocks south of the main museum. The original galleries represent the strengths of the Canadiana collection:

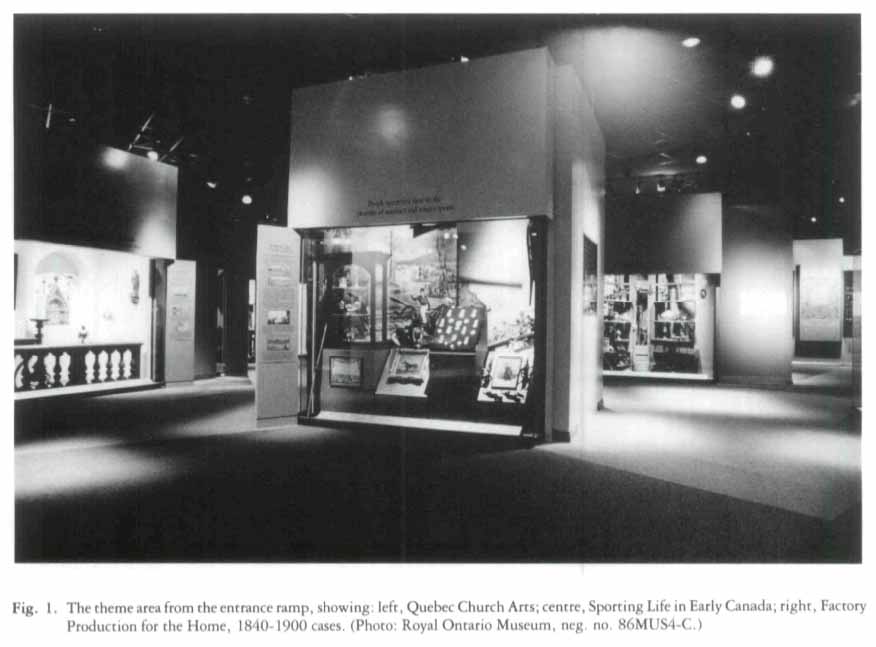

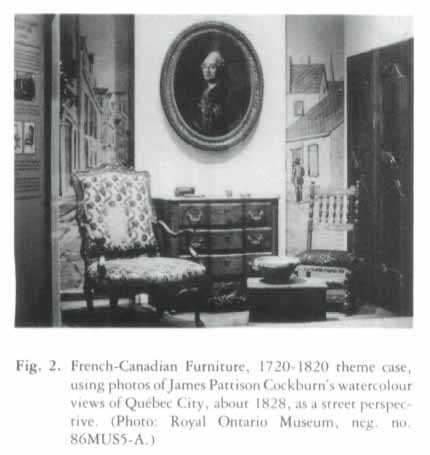

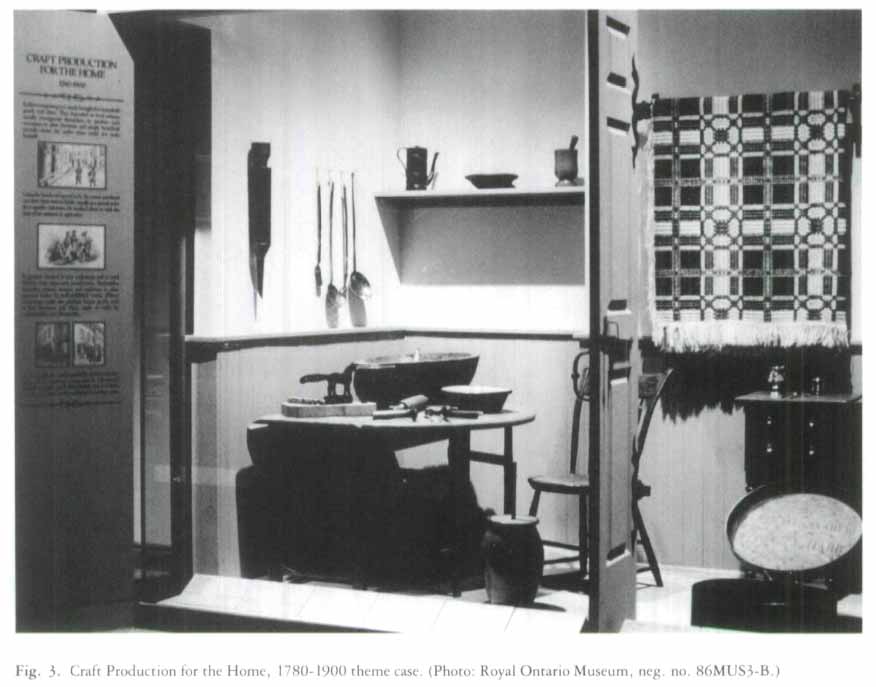

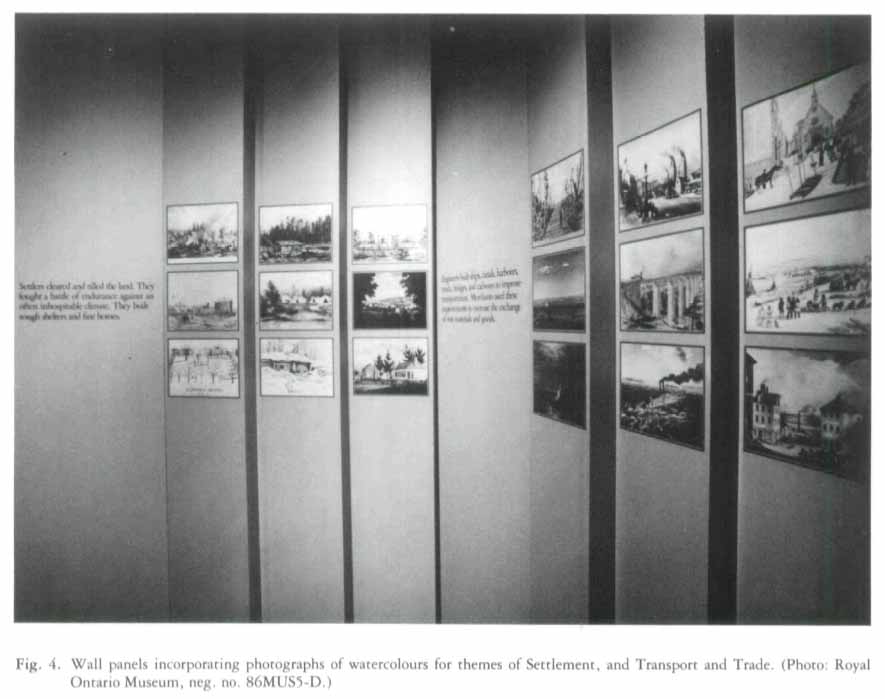

2 The new gallery is housed in less illustrious surroundings in the basement of the main building. Its stated objectives are two-fold: first, to show outstanding examples of craftsmanship or artifacts associated with notable Canadian people and events and, second, to show the development of Canada in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries from "a sparsely populated wilderness to an industrial nation" through the themes of exploration, settlement, production and trade. In keeping with the two objectives the exhibit is physically divided in half. Section 1, "Treasures of Canada," is a series of free-standing cases highlighting artifacts such as an early nineteenth-century tin weathercock, a powder horn that belonged to General Richard Montgomery, a tall clock fashioned by G. & H. Bellerose between 1810 and 1820, and the painting by Benjamin West, completed in 1776, entitled The Death of Wolfe. Section 2, "A Mirror of Canada's Past," utilizes large theme cases to interpret various aspects of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Canadian development: Exploration; Quebec Church Arts; French-Canadian Furniture, 1720-1820; English-Canadian Furniture, 1780-1825; Empire and Victorian Furniture, 1825-1880; Lighting; Craft Production for the Home, 1780-1900; Factory Production for the Home, 1840-1900; The World of Childhood; and Sporting Life. With some exceptions, each case is designed to be a self-contained vignette representing a generic interior (church, shop, room). The case is framed by text panels on either side and topped by an introductory statement; for example, the statement for "Quebec Church Arts" reads "Congregations adorned their churches with the finest pieces of woodcarving, furniture and silver." Object labels are set at ankle height along the front of the case. Further interpretation is provided by "wall statements" which are groupings of illustrations copied from a variety of pictorial sources in the Canadiana Department's collection. Placed at intervals throughout this section of the exhibit, they reiterate the themes of settlement, production and trade.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 In preparing this review I visited the Canadiana Gallery several times. On first impression it was an aesthetically pleasing environment within which to pass a contemplative afternoon. On second and subsequent occasions it was still an aesthetically pleasing environment but one better designed to promote confusion than contemplation. The exhibit attempts to accomplish too much in the 320m2 allocated to it. In my opinion the primary difficulty lies in the duality of the theme. On the one hand the "Treasures" section presents the decorative arts to the viewer - a selection of pristine artifacts notable for their inherent aesthetic value and provenance. On the other hand, the "Mirror of Canada's Past" presents major themes of Canadian social and economic history. Janet Holmes of the Canadiana Department wrote:

To compensate for this perceived omission the design team superimposed people onto a decorative arts picture. The result is an interpretation of both artifacts and economic/social history that is below the standard expected of a major provincial museum.

4 While objects are well-documented and presented within the "Treasures" area, those in the "Mirror of Canada's Past" are sometimes so subtly labelled as to be almost indistinguishable from one another. For example, in the theme case "Empire and Victorian Furniture, 1825-1880" I question whether the average visitor is able to identify a tea-caddy, shaving stand, or ewer and basin without a plan of the case. An interesting display of lighting equipment is also marred by inadequate labelling. Similarly, not one of the remarkable collection of water-colours used throughout the exhibit in "wall statements" and text illustrations is identified. Upon subsequent investigation I found that an unlabelled mural backdrop used in the "English-Canadian Furniture, 1780-1825" case was enlarged from a Montréal scene dated 1845.

5 The choice of room settings as background does not enhance the presentation of the development of the decorative arts over a lengthy period of time. As the curator of a historic house museum I expect a period room setting to represent a particular period or place in time. It is confusing to see a room depicting "Craft Production for the Home, 1780-1900." Objects within this case did not necessarily exist coincidentally in either time or place.

6 These are small drawbacks, however, in comparison to the exhibit's interpretation of Canadian history. It would be virtually impossible for any display of this size to accomplish the objectives outlined on the introductory panel:

The attempt to accomplish these ends results in a bland and sometimes misleading presentation of eighteenth-and nineteenth-century history. Although ostensibly linked by the wall statements on settlement, transport and trade and leisure, the cases remain a series of disparate images representing the strengths of the ROM's Canadiana Collection rather than a coherent vision of a nation's history.

7 As a compulsive label reader I turn to the written word for assistance in developing a conceptual framework, but introductory statements like "explorers travelled thousands of miles across a continent and around its shores" left me hanging. Text panels and wall statements generally offer no further explanations. Where provocative thoughts do exist they are often not defended. One text panel asserts that "providing light for evening work and recreation was a major preoccupation of 19th century Canadians. Even in southern Ontario, there are only nine hours of daylight in mid-winter" Developments in lighting are then reviewed. This lust for lighting is drawn out of proportion and overshadows other more pressing concerns of everyday life. As Jeanne Minhinnick wrote: "We accepted the lack of uniform light as we accepted the lack of overall heat. We accommodated ourselves to the lack of light by habits and behaviour which have now completely gone."3

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 The strongest impression left by this gallery is of Canadians as a nation of contented, middle-class people pursuing their daily lives amidst harmony and stability. Where change is suggested by the craft and factory production units there are no allusions to the repercussions of industrialization on either people or the environment. Nor is there anything to suggest that the standard of living represented by the artifacts on display was beyond the reach of many Canadians. A "mirror" should reflect the original image precisely, warts and all.

9 I left the Canadiana Gallery with deep misgivings. The Royal Ontario Museum ought to be a leader in the exhibition and interpretation of Canadian artifacts. Rather than creating a restatement of existing exhibits, could not space have been provided within the main building for important temporary exhibitions on the decorative arts in Canada? Living history sites across the province are grappling, successfully and unsuccessfully, with the means of documenting and presenting people and the processes of production. It is an exciting movement, but by trying to inject this kind of excitement into the new Canadiana Gallery, the ROM has neglected the inherent attraction and significance of the object, presented a too selective version of Canadian history and failed to fulfill its enormous potential to provide a bench-mark introduction to Canadiana.

Curatorial Statement

10 When the Canadiana Department was approached in January 1984 and asked to plan a new Canadiana gallery in the ROM to open early in 1985, there were already in place several elements that would affect that development. One was the shaping role played by the formation of the department and its collections. A second was the current stage of development of Canadian decorative arts studies. A third was that the department's detailed study galleries would continue in their present form and location in the separate Sigmund Samuel Canadiana Building.

11 The donation between 1940 and 1952 of Sigmund Samuel's collection of late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Canadian topographic and historical views, portraits of Canadian people, and maps and medals of Canada created a need for a separate Canadiana Department. It was formed in 1952, patterned after its parent, the European Department, which in turn was modelled after the decorative arts model of the Victoria and Albert Museum. These two influences from the outset created for the department a national rather than a provincial geographic boundary, and set the department's collecting focus.

12 As a field of study, Canadian decorative arts are still comparatively young, having developed over the last forty to fifty years. Like their earlier European and American counterparts, studies have been material based: furniture, woodcarving, glass, ceramics, metalwork, textiles. This is true of the earliest introductory surveys and of the later collective anthologies, where chapters are defined by material. It is also true of the more detailed studies, whether they are directories of craftsmen, studies of the work of individual craftsmen, the craft production of a town, province, region or whole country. In the European context decorative arts are usually studied as innovative designs of fine quality by known designers and craftsmen. For Canadian silver, for some woodcarving, textiles and ceramics, and for a very small amount of furniture, this approach to the material is possible. However, in the Canadian eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonial and early industrial context, studies more often become the tracing of stylistic influences and traditions in the work of anonymous craftsmen. It is at this point, and particularly in the materials of glass and ceramics, aided by archaeological excavation, that studies broaden out from concentrating simply on the finest quality decorative arts to include investigation of the whole range of Canadian production. They also merge with the even broader field of Canadian material history, of which they form a part. To date the works that have attempted to define and understand a whole period or culture are much rarer. As examples I think or Jeanne Minhinnick's At Home in Upper Canada (Toronto: Clark, Irwin & Company Limited, 1983); Scott Symons' Heritage: a Romantic Look at Early Canadian Furniture (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1971); and, Donald Webster's Georgian Canada: Conflict and Culture, 1745-1820 (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, 1984).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 313 Our galleries in the Sigmund Samuel Canadiana Building (650m2) necessarily reflect the decorative arts focus of our collections and follow the material-based structure used by current studies in the field. They show the fine art of Quebec religious woodcarving, the decorative arts of furniture and silver, the utilitarian crafts of woodenware and pottery, and the industrial designs of early Canadian glass and pottery factories. Changing south gallery exhibitions are assembled from our picture collection to show late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century life as recorded by our early artists. Together these exhibits also reflect our collection's major strengths. These galleries will continue to be the department's primary galleries, with little revision until the ROM's whole gallery development project is completed.

14 With these elements as a framework, we began plans for the 320m2 of new gallery space in the ROM building. A gallery design team was set up. It included the four Canadiana Department curators, three of whom had other major commitments during the year. Donald Webster, curator from January to July, was working full-time on the Georgian Canada special exhibition. Mary Allodi, associate curator, was on sabbatical leave from July to December researching Canadian portraits. Honor de Pencier, curatorial assistant, was involved in planning two Canadiana Building temporary exhibitions. Curatorial tune available was one person full-time, one part-time, and two tor specific requests related to their subjects, for occasional attendance or planning meetings, and always for quick consultations. The core planning group included Honor de Pencier and myself, David Lloyd, designer, and Steven Spencer, programmer, from our Design Department. At a later date, a Conservation Department co-ordinator, Izabella Krasuski, and a graphic designer, Kim McConnell, were added to the team.

15 In this gallery we chose to do two things: provide an introductory overview and create an advertisement tor the more detailed displays in the Canadiana Building. The gallery area is divided in two parts. A section of 90 m shows eleven fine examples of painting or decorative art selected from each major category represented in the collections. They were chosen to show the artistry and skill of Canadian craftsmen or for their close historical association with Canadian events or people and are displayed as separate individual pieces. The remaining 220 m is an area of theme cases. In this section, rather than repeat the material-derived divisions of our Canadiana Building displays, we have drawn on material from all parts of our collection to create an introductory survey of selected aspects of Canadian material history. The three-dimensional themes are: Exploration; the decorative arts in Quebec Church Arts, French-Canadian Furniture, 1720-1820, English-Canadian Furniture, 1780-1825, and Empire and Victorian Furniture, 1825-1880; the transition from craft to factory production in Craft Production for the Home, 1780-1900, and Factory Production for the Home, 1840-1900; Lighting; the World of Childhood; and Sporting Life. There are also three supporting pictorial themes: Settlement, Transport and Trade, and Leisure.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 416 In this area the basic 1.8 m x 2.4 m case format has been designed with maximum flexibility to make future exhibit changes easy. Rather than create a linear, chronological, programmed route through this theme area, a cluster layout groups related themes together. This choice is both a philosophical one, allowing free selection in viewing, and a physical one, providing wide corridors through to the Musical Instruments and future Textile galleries, located beyond the Canadiana Gallery. It also allows ample room for the accommodation of school groups. Case design with glass from the floor to the 2.4-m level is intended to make viewing easy for children, standing or sitting.

17 As a form of conveying information, this type of introductory exhibit is briefer in text and material objects than the typical condensation of information found in an illustrated encyclopaedia article. Background text for each theme becomes historical journalism at its most basic, answering the reporting questions of who, what, where, when, why, how. This information for each theme case is on a text panel that extends from an exterior corner of the glass window and rises its full height, making it readily available. Additional information about each object is on a sloped floor-level carrier, in separate 22-cm sections to allow for easy substitution of the objects and their labels.

18 The matching selectivity in the objects displayed creates a shorthand of visual symbols. In the early stages of design, the curators requested from David Lloyd a stark design showing objects against a uniform-coloured background. Although he produced this design, both he and Steven Spencer had reservations about this "fine art" treatment of the objects, in which they appeared as isolated but essentially unrelated items. David recommended instead that the design should display theme material in a visual context parallel to that of the written story, an approach that the team adopted. Like a painting this composes the visual information so that it is viewed initially as a single unit, from which details can then be selected.

19 Each theme case with its text panel, labelling and visual presentation of the objects selected provides a self-contained body of information. To link the individual themes together we have used a single sentence theme line above each case that speaks of the men and women who came to Canada and created or used the objects shown in the case. Visually we have tried to accomplish that same linking together by using images of nineteenth-century Canadians from our watercolour collection. Because prolonged exposure to light causes watercolours to fade, we have used these images in the form of coloured photographs. This decision also has given us greater flexibility in incorporating this visual information: as wall-sized photomurals showing the houses that furnishings might have belonged in or showing a view of King Street, Toronto, in 1880, from the window of the store in the Factory case; as small views directly related to the background text and incorporated into each text panel; and on the gallery walls for the three pictorial themes of Settlement, Trade and Transport, and Leisure.

20 The gallery attempts in an introductory survey for a general audience to show the range and quality of late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Canadian decorative arts. In the theme area it traces the achievement of the many anonymous people who explored and settled Canada, who transplanted their decorative traditions, who recreated the comforts and social life of home, and who in a few centuries transformed Canada from a sparsely populated land to the beginnings of an industrial nation.