Articles

Monuments and Memories:

The Evolution of British Columbian Cemeteries, 1850-1950

Résumé

C'est dans les cimetières que les gens expriment le plus tangiblement et le plus ouvertement leurs réactions à la mort. L'article s'attache aux cimetières de Colombie-Britannique; il analyse l'évolution de leur esthétique de 1850 à 1950, la façon dont ils étaient compartimentés et les monuments funéraires qui s'y trouvaient. Le jardin du XIXe siècle on la famille rendait visite» à ses défunts a graduellement cédé le pas, au XXe siècle, à des pelouses, ce qui a rendu la présence de cimetières de moins en moins manifeste. Bien qu'il ne serve plus de refuge à la famille du défunt, le cimetière demeure un lieu où les distinctions sociales sont bien établies, tout au moins pour la classe moyenne qui en contrôle la regimentation. Les gens ont fini par délaisser les cimetières, préférant conserver intérieurement le souvenir de leurs proches.

Abstract

Cemeteries represent the most material, and therefore public, means by which people express their reactions to death. This article analyzes the changing aesthetic qualities of British Columbian cemeteries between 1850 and 1950, the physical divisions created within them, and the monuments that populated them. A nineteenth-century garden where the family "visited" the deceased evolved into an increasingly invisible twentieth-century lawn cemetery. For the middle-class people who controlled cemetery regulations, the graveyard remained a place where social distinctions were established, although it had lost its role as a refuge for the mourning family. By 1950, the mourners' memories had supplanted the cemetery as the final resting place for the deceased.

1 Today, the cemetery impinges much less on everyday life than it did in the nineteenth century. Increasingly inconspicuous and less frequented, the modern burial-ground seems an anomaly in the urban landscape. Since mid-century, contemporary attitudes toward death, like the cemetery they created, have become objects of criticism. At first criticism focussed largely on the unnecessary extravagance of the death ritual;1 more recently it has been levelled at a perceived indifference toward death or the dying.2 Now historians are providing a context for these critiques. Richard Etlin, in his study of cemeteries in France, states, "Our current indifference toward the cemetery...stems largely from taboos of openly discussing death and providing for the dead."3

2 The evolution of our modern-day cemetery from the nineteenth-century burial-ground can be clearly shown. Starting with the premise that burial-grounds can be seen as places where social distinctions and ties are made and unmade, this article examines the evolving middle-class attitude toward the physical consecration of death in British Columbia. Discussion focusses on the cemeteries in the province's largest urban centres, where the shifting forms of the graveyards take on their clearest outlines. In looking at monuments, however, the most accessible published evidence comes from smaller cemeteries. In the period from 1850 to 1950, although the cemetery remained an appropriate place for drawing social distinctions, its physical importance in the process of dealing with death diminished. By 1950, the memory had replaced the cemetery as the final resting place of the dead loved one.

3 The early white settlers of British Columbia undoubtedly brought with them recollections of how their home societies disposed of their dead. Governor James Douglas' son-in-law, Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken, recorded in his memoirs the uneasy feelings he entertained during his explorations of the burial vaults in his parish church in London.4 Such burials, relatively common up to the early nineteenth century, were generally reserved for persons of status and wealth. Others had to content themselves with less distinguished resting places. Churchyards and graveyards, often no more than mass burial pits, bequeathed memories of miasmatic vapours and exposed rotting remains.5 By the early nineteenth century, urban reformers in both western Europe and North America were invoking sanitary and sentimental justifications to close the old burial-grounds and open garden-like cemeteries outside the city limits.6

4 Given the uneven nature of British Columbian development, it is not surprising that burial-grounds should, especially in the early years, display wide variations. In isolated areas, or among specific groups in society, the dead were not even interred in graveyards. Dr. Helmcken buried two of his infants in his own garden, transferring them to a cemetery only on the death of their mother.7 Early travellers to the interior of the province, at a time when organized graveyards were rare, thought it noteworthy, but not shocking, to find graves alongside the trails they were following.8 As late as 1892, Charles Mair, an ex-member of Canada First, employed his poetic licence to express his enthusiasm over the lack of a graveyard near Kelowna:

5 In small communities, as Roger Hall and Bruce Bowden point out in the case of Ontario, rural cemeteries remained aloof from the social forces influencing their urban counterparts.10 Haphazard borrowings from North American and European influences created an eclectic blend of graveyards in British Columbia. Comparing these rural burial-grounds to those in Ontario, geographer Mary Philpot explained, "It is not so easy to stereotype the British Columbian cemetery."11 Nonetheless, in the urban areas of the province, the evolution of cemeteries traced a similar course to the trends in other parts of the Western world.

6 British Columbian cities reached early agreement that burial-grounds should be distinct and isolated, that the dead should be banished from the sight of the living.12 In recommending the approval of the Anglican bishop's plan for New Westminster, Colonel R.C. Moody wrote to Governor Douglas that "His Lordship impressed upon me the immediate necessity of a Burial Ground outside the limits of the City."13 Likewise, when B.W. Pearse judged the viability of various sites in Victoria, he stated that "nearly all of these lots would be suitable for a Cemetery, being well away from the City...."14 As a result, when Victoria established Ross Bay Cemetery in 1872 and Vancouver created Mountain View in 1887, both sites were quite distant from populated areas.15

7 Civic officials were only reflecting the accepted notions that cemeteries offered a menace to the public health. The first draft of an 1860s petition for the closure of the small graveyard established by the Hudson's Bay Company in Victoria in 1848 cited the facts that

As late as 1895, Nanaimo's Board of Cemetery Trustees considered closing the Old Cemetery because a public health official warned of the dangers of infection.17 Thus, concerns for the living, rather than the dead, resulted in the isolated location of cemeteries. But this did not mean that the living were unconcerned about the dead.

8 Rather, public interest had a great deal to do with the shape the graveyards took. "I felt impressed today with the importance of doing something to improve our public Cemetery which is in a disgraceful condition," the Reverend Edward White recorded in his diary in 1867 in New Westminster, "went to the president of the Council and something may be done."18 The following year in Victoria, a public committee proposed draining the Quadra Street Cemetery, constructing walks, and planting it with ornamental trees and shrubs.19 The monuments that mourners provided for the commemoration of the deceased also contributed to the aesthetic development of the cemetery. With the transformation of burial-grounds into peaceful, beautiful gardens, the dead were being rendered accessible to the living.20 In doing so, those people in charge of cemeteries stressed the links between the living and the dead, and to a certain extent, the cohesion of the community itself.

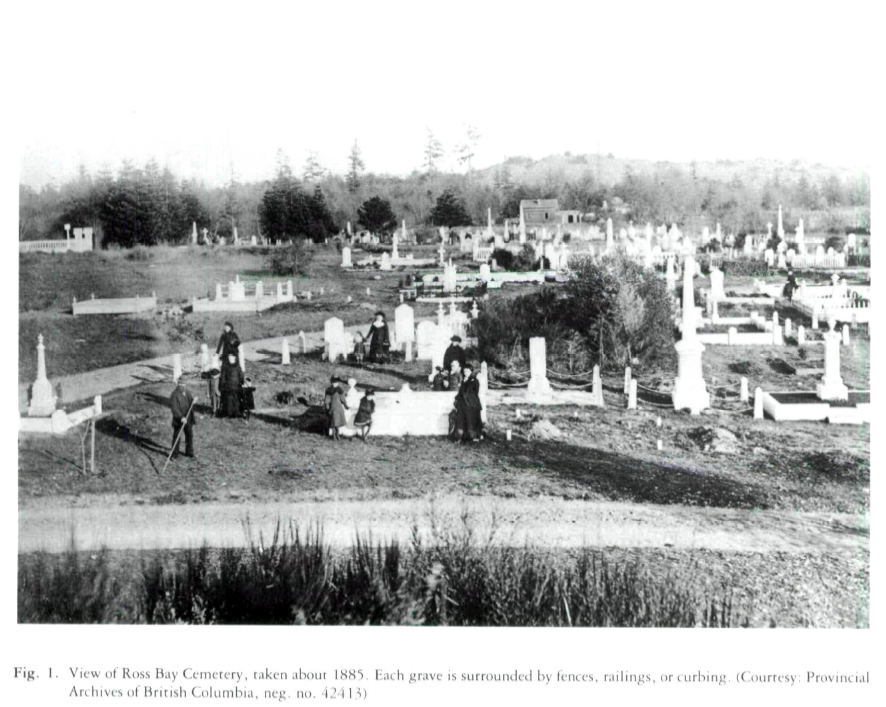

9 But in a more striking sense, nineteenth-century cemeteries accentuated the primacy of the nuclear family. Early photographs illustrate the point. Fences, iron railings and concrete curbing enclosed the graves, carrying into the necropolis ideals of privacy and property (fig. 1).21 When Lady Franklin visited Victoria in 1861, Alexander Grant Dallas, a director of the Hudson's Bay Company, took her to the local graveyard one Sunday after church. It was a matter of civic pride as well as pious familial grief to show the distinguished traveller his child's tomb.22 The early urban British Columbian cemeteries emphasized the sanctity of the family, the sense of peacefulness and beauty, and the focus on public health. The graveyards promised both an escape for the dead from the sprawl of the young cities and their eventual reunion with their mourners in fenced private plots. In this way, the cemeteries embodied many aspects of nineteenth-century attitudes towards death.23 Banished from everyday sight, the dead nonetheless remained accessible to the living, if only on the latters' own terms.

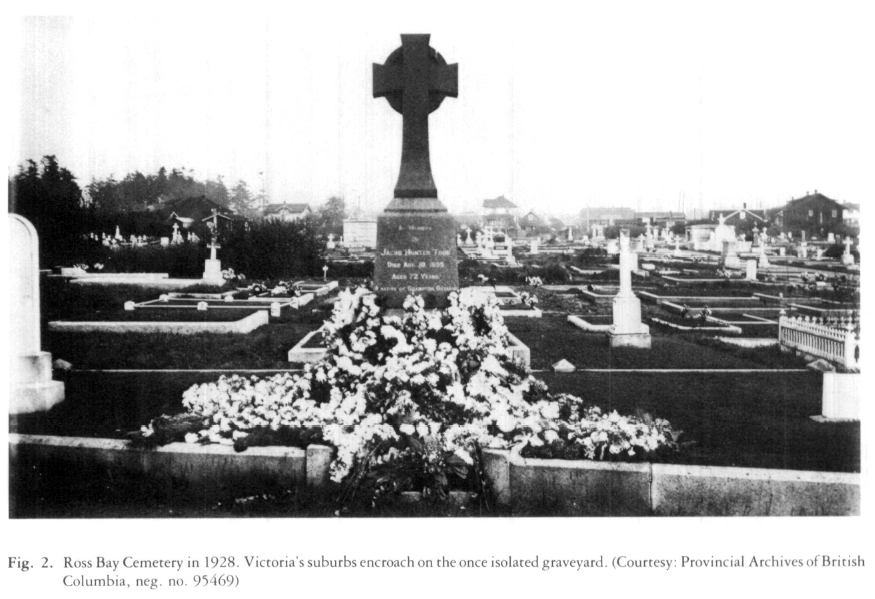

10 The banishment of the dead would not last long. In the face of rapid urban growth in Vancouver and Victoria, the isolated nature of their cemeteries was soon lost (fig. 2). As old sites filled up, debates over the creation of new burial-grounds revealed an evolution in the concept of the cemetery. Where once the garden graveyards had been a source of civic pride, many now saw them as a direct challenge to suburban self-esteem. Vancouver's city council overcame the problems of overcrowding in Mountain View by expanding the original site. In 1920, the South Vancouver Board of Trade complained to its Member of Parliament, "We have no ambition or desire to become a City of the 'dead'."24 Another petition in 1935 to the city's mayor stated the problem more clearly:

The presence of the dead, therefore, challenged the property values of middle-class homes. The reference to Point Grey is appropriate since only nine years previously a concerted protest by politicians at every level of authority averted plans for a private cemetery in the suburb. At the time, a committee report argued successfully to the provincial premier that

In the twentieth century, faced with a suburban public reluctant to accept daily reminders of death, a successful cemetery would become one that dissimulated its morbid nature.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 The stone jungle of upright monuments of the nineteenth-century garden cemetery gave way to manicured lawns and almost invisible memorials. In the late 1920s, during a period in which Vancouver's city council flirted with the possibility of disposing of its dead in an acreage it had purchased in Burnaby, it commissioned a report on the ideal forms a burial-ground should take. "In order to prevent this undue animosity," the author noted, recognizing the suburban opposition to cemeteries, "the modern cemetery, resembling a park, with its tablet system of memorials, has been evolved."27 Cemetery ordinances were increasingly strict concerning the size and shape of monuments. The 1924 bylaws of Burnaby's own cemetery, Ocean View Burial Park, set out very specific conditions for the erection of monuments.28 Similarly, in those sections of Mountain View Cemetery opened after 1933, only flat, horizontal tablets were permitted.29 Victoria's leading funeral director, Reginald Hayward, explained to an English client the rules of Victoria's Royal Oak Cemetery, the 1920s answer to crowding in Ross Bay:

Even more important than its attractiveness, the modern cemetery promised easier, more efficient maintenance. It also, American historian James Farrell argues, "eliminated suggestions of death."31

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 Furthermore, by disallowing fences and curbings, they seemed to eliminate the emphasis on the family. Enclosures had largely disappeared from the rural cemeteries of southwestern British Columbia by 1925.32 The report commissioned by Vancouver's city council remarked on a similar trend. Where once four-grave units had been popular among purchasers of cemetery plots, two-grave units were increasingly in demand.33 The reunion of the family after death was becoming less and less likely. Cemetery regulations, and perhaps society in general, were frowning on the expressions of property and privacy that were so common to graveyards of the nineteenth century. In 1940, the owner of a plot in Mountain View declared his intention to cover it with a sheet of concrete. The owner of the neighbouring plot complained to the mayor,

The city council agreed; if individuals wished to express property and family ideals, they would have to employ less material means. In any event, expressing links with the dead was becoming an intellectual exercise that required the cemetery less and less.

13 Although the family's identification with the dead was less and less centred upon the grave, the cemetery remained, up to 1950 at least, an appropriate place to create and recognize larger social identifications. On the broadest level, of course, there was a feeling that the cemetery should reflect the overall unity of the community. All sectors of society were allowed into the public cemetery (though certain groups, for example, the Chinese in Victoria and Kamloops or the Jews in Vancouver and Victoria, chose to establish their own burial-grounds). Thus H.P.P. Crease wrote to the Attorney General in 1863, "The lines of demarcation between separate portions should not be such as to prevent the Cemetery being laid out as a whole."35 Nonetheless, the nature of these "separate portions" reveals much about British Columbian society.

14 From the beginning, civic cemeteries permitted religious groups to establish rights over specific areas. In 1860, Roman Catholic Bishop Demers of Victoria complained to Governor Douglas that the Anglican Church was not respecting his congregation's privileges in the Quadra Street Cemetery.36 With the opening of Ross Bay in 1872, various churches received portions of land. Emily Carr recalled the strange visual effects of the religious divisions.

15 In the 1870s, after the Anglican and Catholic churches refused burial rights to individuals who had wished to be interred in the denominations' land in Ross Bay, debate arose over the propriety of granting exclusive rights over sections to religious groups.38 In opposition to a proposed bill, Victoria's Cemetery Trustees petitioned the Legislative Assembly in 1875 to maintain the clergy's rights.39 Likewise, in 1876 New Westminster's Cemetery Board, caught up in government restrictions, demanded the power to divide its property among the denominations.40 In the end, communitarian forces of the period compromised with the churches' tenacity. In 1879 the legislature passed an act requiring the payment of $300 an acre for the retention of privileges in Ross Bay. Only the Anglican, Roman Catholic, and Presbyterian churches paid the sum, and other sections were opened up to the public.41 British Columbia cemeteries, while permitting some religious distinctions, were not to be strictly organized along denominational lines.

16 In fact, cemeteries preserved racial differences more successfully in the twentieth century than they did religious distinctions. The Church of England, at the time of the opening of Ross Bay, vehemently argued that

Although the trustees permitted Asian-Canadians to inter their dead in the cemetery, Chinese, Japanese, and East Indians had access only to an isolated section. That this portion of the burial-ground was undoubtedly the least desirable land was shown by the fact that a strong storm later washed part of the section into the sea.43 Racial restrictions recurred throughout the province. The bylaws of the Ocean View Burial Park Company outlined in 1924 that

The 1928 report on Vancouver's cemetery likewise suggested that a separate portion be provided for Canadians of Oriental origin.45 Such divisions also found their way into many rural graveyards.46

17 No less, and possibly more, important were the economic distinctions the cemetery revealed. Plots varied in size, location, and price, making the ability to buy a plot confirmation of at least a minimum degree of social status. "In the urban cemetery," historians of nineteenth-century Britain have argued, "...the class structure which was developing could be neatly demonstrated by the lines on a map or plan."47 In British Columbia, the major distinction was drawn between those who could afford graves and those who had rejected the norms of middle-class society by not providing for their departure from society.

18 Provincial legislation required the provision free of charge of burial-grounds for paupers; it made no demands as to the sort of ground accorded for the purpose. Consequently, to the end of the period, the thought of a pauper grave struck fear into the hearts of many British Columbians. Funeral directors may have helped create such attitudes, if only because of their cavalier reaction towards the interment of paupers. Reginald Hayward's father, Charles, who had in 1888 complained of the rude conduct of pauper funerals, was quick to suggest a money-saving plan for the burial of the unidentified dead of a shipwreck: "At least four possibly five could be placed in two plots, and the expense considerably reduced."48 For his own part, Reginald Hayward would later dissuade a client from purchasing such a grave. "They are good dry graves," he explained, "but are where the charity cases are put, hence not particularly desirable."49

19 Some members of the public shared this sentiment. "Certain it is that had I been an hour later in arriving," the brother-in-law of an almost unidentified drowning victim dramatically informed the latter's brother, "poor Tom would have been buried as an unknown body in a pauper's grave."50 Mrs. M.F. Kelly, writing to Vancouver's mayor to inquire why her husband's grave was so poorly tended, stated, "One would think it was a section set aside for paupers."51 In a similar vein, a meeting of Victoria's morticians learned in 1942 that "a buyer...ordered a $20.00 grave through his Funeral Director and...was mortified to find the grave dug in the pauper section."52

20 In fact, economic distinctions even overcame the racial restrictions so important to local cemetery boards. Cemetery records for the first years of operation of Mountain View report the adjacent burials between 22 December 1888 and 5 January 1889 of James McAfeeley, a "Chinaman," William Sweeney, and Kandi a "Jap."53 As a witness before a legislative committee examining Ross Bay Cemetery had admitted some twenty years previously: "There is a spot set apart for Indians, Mongolians, and paupers."54 Thus, poverty may have been in British Columbian cemeteries the ultimate social distinction.

21 However, cemeteries do not only enforce distinctions: they may also reinforce social ties. As Philippe Ariès states, the nineteenth-century garden cemeteries were "museums of family love."55 A closer examination of the monuments that were dedicated to the dead "loved ones" reveals elements of the family's relationship with the deceased. Although on first glance, the increasing invisibility of headstones might suggest for the twentieth century a studied ignorance,56 a closer look reveals just the opposite.

22 The earliest cemetery legislation accorded local boards the jurisdiction to accept or reject personal monuments.57 In the heyday of Victorian mortuary art, however, a wide variety of columns, obelisks, pedestals, sarcophagi, and tablets dotted the landscape of the garden cemeteries. Most of these memorials had a vertical axis, as if by reaching towards heaven they breached the distance between the deceased and his or her mourners. Philpot demonstrates that the vertical nature of British Columbian tombstones peaked around the turn of the century. In addition, she shows that they reflected the designs, themes, and materials current in other parts of North America.58

23 Yet by the 1920s, at least in urban areas, horizontal headstones set flush to the lawn had taken the place of the diverse styles. "By 1925," Philpot notes, "tombstone art seems to be directed towards functional purposes rather than artistic expression."59 Stereotyped and shortened, memorials were increasingly nondescript.

24 Uniformity was, in fact, universal among those buried as war veterans. Subsuming individual identity to the larger national cause, cemetery officials were vigilant in controlling the regularity of the rows of monuments. In 1931 Mountain View's superintendent J.B. Gray complained of a "disagreeable circumstance":

In 1942 the erection of a cross on a soldier's grave occasioned a similar crisis. A city official wrote to a representative of the army, "I feel that we shall have to remove the cross so that uniformity may be preserved." Although uniformity was never so rigid in other parts of the cemetery, the diverse monuments of the nineteenth century found only a faint echo in the twentieth. In this sense, the war veterans' memorials perhaps typified only an extreme example of the modern tendency.

25 The decreasing size and the increasing uniformity of the monuments complicate an analysis of the epitaphs inscribed on them. Not surprisingly, the epitaphs tend to grow shorter throughout the period. Nonetheless, a quantitative study of the inscriptions provided in lists compiled by genealogists and in the order forms of Kamloops mortician R.H. Dwyer reveals some more significant trends.62 These epitaphs, from relatively small urban, suburban, and rural graveyards, were probably less influenced by the rigid regulations of the twentieth century than were gravestones in the larger cemeteries. They may therefore provide a clearer reflection of the attitudes of the people who chose the inscription.

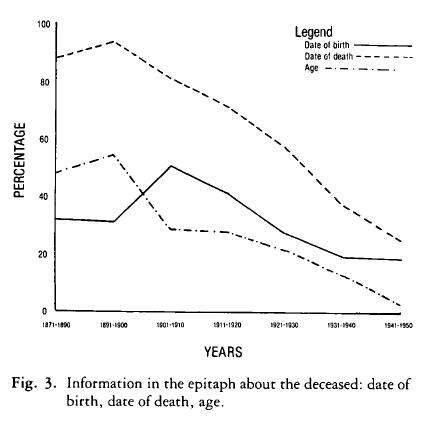

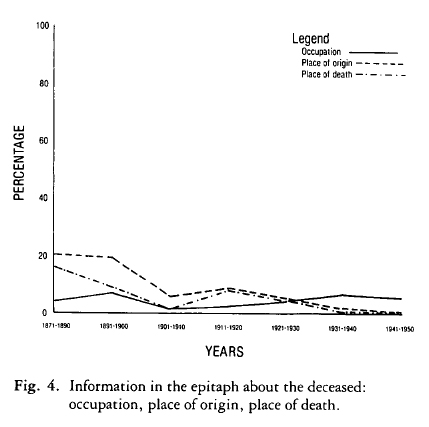

26 In his study of American epitaphs up to 1813, Michel Vovelle shows that the inscriptions illustrated a growing mastery over the facts of the deceased's life. For example, by the early nineteenth century, tombstones almost universally noted the age of the dead and frequently the place of birth as well.63 This trend reversed in British Columbia. Between 1870 and 1950, it became less and less common to provide precise vital information such as the exact dates of death and birth and the age of the deceased (fig. 3). Likewise, fewer epitaphs referred to other aspects of the deceased's life (fig. 4). The proportion of tombstones noting place of origin or place of death declined, and if the data on occupations are slightly more vague, this fact is due to the rising number of war veterans who died in the latter part of the period. Their tombstone specifications required an indication of their military occupation. In the twentieth century, much less stress was put on the specific attributes of the dead loved one on British Columbian gravestones.

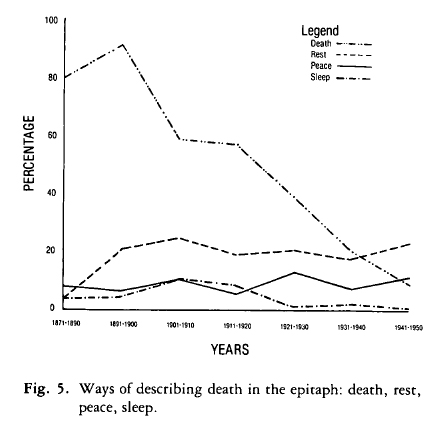

27 At the same time that there was a decreasing emphasis on the individuality of the deceased, it became less and less clear just what he or she was doing in the cemetery. The use of direct terms such as "died" or "death" (including obvious euphemisms like "gone" or "passed") declined dramatically over the period (fig. 5). Even life-like metaphors such as "rest" and "peace" increased in popularity only marginally, while "sleep" remained very low. Perhaps British Columbians gradually realized that it was unnecessary to indicate the purpose of the deceased's sojourn in the cemetery; perhaps also they were shunning a direct, material confrontation with mortality.

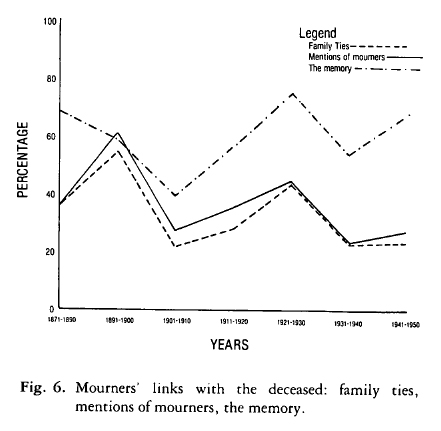

28 Of course, the shrinking size of the monument might provide a facile explanation for these declining trends. One set of graphs (fig. 6), however, suggests the inadequacy of this argument. The proportion of mentions of the family ties of the deceased remained relatively consistent over time, as did references to the mourners. Faced with the finality of death, the survivors proved unwilling to forsake their links with the dead. But these ties with the deceased could only exist in the mind. Thus, the use of the term "memory" ("remember," "in memoriam") actually seems to increase, although unsteadily, through the period. In this way, the historical process that had created the garden cemetery in the nineteenth century as a place for the forging of family memories led to a point where those memories took primacy over the cemetery in the twentieth century. The mind represented one place where the dead would be perpetually accessible to the living. In more than just the codified move to a horizontal axis, then, twentieth-century tombstones brought death "down to earth." There the mourners, especially the family, could refuse to relinquish their ties with the dead by encircling the loved one in their memories.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 629 Cremation, as S.C. Humphreys points out, provided an even more efficient means of encircling the deceased in memories. Ashes could be dispersed in spots reminiscent of the dead person's lifetime.65 At least two churches in Victoria allowed the burial of cremated remains within their buildings after the 1930s.66 More significant was the ability to scatter or bury ashes outside of traditional areas. One client, Reginal Hayward learned,

For people who cremated the remains of their loved ones, no material presence, whether it be the corpse or some form of monument, stood between the deceased and the mental process of commemoration.

30 Up to 1950, however, cremation remained quite uncommon in British Columbia.68 Much more common was burial in a lawn cemetery beneath a small, flat tablet that stressed the deceased's ties to the mourners. The family had not disappeared from the new cemetery; rather, the family's memory had supplanted the function of the old graveyard. Where the dead had been banished from sight in the nineteenth-century garden cemetery, they were relegated to the mind in the twentieth. At the same time, the cemetery continued to play a role in fostering social distinctions. Though religion did not provide strict lines of segregation in the cemetery, well into the twentieth century economic and racial differences remained very important. But overall, the cemetery assumed a less imposing place in the landscape. For the middle class in British Columbia, the family ties, which had hitherto been consecrated in a public fashion in the cemetery, would become more and more a matter of the mind.

I would like to thank Dr. W. Peter Ward, who directed the thesis that provided the material for this article, and Megan Davies, who commented on the various drafts it later underwent.