Articles

Inside the Hallowed Walls:

Convent Life through Material History

Résumé

La communication étudie la nature de la vie dans un couvent, en examinant l'histoire matérielle d'une communauté religieuse. Elle décrit, entre autres, la structure spatiale du premier couvent établi dans le sud du Nouveau-Brunswick, des objets et des habits religieux. La discussion fait état des difficultés auxquelles se heurtaient les communautés apostoliques pour servir le public tout en continuant à mener une vie de prière. On mentionne que les efforts consacrés à améliorer le service à la population ont grandement diminué l'importance de nombreuses formes extérieures de dévotion. Ces objets, maintenant relégués dans les musées, constituent le poignant témoignage laissé par une organisation sociale catholique et religieuse qui représentait autrefois la carrière féminine par excellence.

Abstract

This paper is an inquiry into the nature of convent life through an examination of the material history of a religious community. Consideration is given to the spatial structure of the first convent built in southern New Brunswick, convent artifacts, and religious habits. This discussion touches upon the tension within apostolic communities of having to address both the services dimension and the prayer life. In this paper it is observed that in the course of attempting to improve the services dimension much of the externals of the prayer life receded in importance. These artifacts, now relegated to museums, serve today as a poignant material legacy of a Catholic religious social organization that once functioned as a compelling career route for women.

A Saint John Religious Community

1 In 1952 Pope Pius XII urged the superiors general of religious women world-wide to educate members of their congregations on a par with other professionals. Although implementation of this directive was expected to create some disruption, it is doubtful that anyone could have predicted the upheavals of the late 1960s within religious institutes. The transformation that occurred, especially after the Sister Formation Movement in the late 1950s and Vatican II in the early 1960s, resulted in a well-documented exodus from religious communities which had previously succeeded in attracting many women to commit themselves to a lifetime in service to others. In short, by 1970 the structure of the Religious Life had been altered, perhaps forever.1

2 One consequence of this alteration was to render obsolete many large convents and many of the external trappings of monasticism, such as the religious habit (or clothing). Within a few brief years objects that had once been synonymous with religious life became artifacts on museum shelves, and in some cases, such as Buctouche, New Brunswick, convents were converted into museums.2 Although much of the collectivism of religious life appears to be a phenomenon of the past, the material legacy of that past remains to provide us with a glimpse into a form of social organization that responded to the needs of the Catholic community while simultaneously offering an alternative career route to young Catholic women.3

3 The congregation principally under discussion here — the Sisters of Charity — was founded in the Diocese of Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1854. Along with its diocesan counterparts in the United States and Canada, the Saint John diocese had experienced an influx of Irish Roman Catholics in the 1830s and 1840s. Many of these, as is well known, remained in the seaport communities that received them, often clustering at the lower economic levels. The Church, the one constant in the trans-Atlantic migration, was morally charged and challenged to provide not only religious solace but more immediately an institutional response to a host of temporal crises.4

4 In Saint John, Bishop Thomas Louis Connolly proceeded to organize an essentially church-based social service system for his diocesan congregation. The mechanism by which such a system could be effected conformed with the familiar North American pattern: either secure the services of an existing religious congregation of women or establish within the diocese a congregation designed to assume such responsibilities.5

5 Connolly, an Irishman whose North American clerical career had begun in Halifax, took up his New Brunswick duties in 1852. Almost immediately he sought for Saint John the services of those religious institutes having convents in Halifax — institutes with which he was familiar and with which he had worked closely while stationed in that diocese. Thus, the bishop wrote to Mother Hardey of the Religious of the Sacred Heart at Manhattan-ville, New York, asking that she establish an academy for girls in his diocese, claiming that he had promised the well-to-do families that he would have a Catholic academy in their city in a few years. He wrote as well to Mother Jerome Ely of the Sisters of Charity, also based in New York, seeking the services of her community to care for the sick and aged and to set up primary schools for the poorer classes. Connolly's initial requests met with little success. Each superior general responded that her respective congregation was already spread thinly and that there were no sisters to spare for mission purposes.6

6 Bishop Connolly was still in the process of trying to secure a convent foundation for the diocese when the cholera epidemic broke out in Saint John in the summer of 1854. Connolly's requests now assumed a desperate urgency. He reminded the Religious of the Sacred Heart that while he had been in Halifax he had acted as their "chaplain, confessor, architect and business agent" and now with "seventy orphans on my hands" he needed them.7

7 Possibly it was the severity of the circumstances of 1854 that prompted Connolly to journey to New York and personally plead his case before the superiors of these congregations. He succeeded. Mother Hardey agreed to assign four sisters to Saint John to care for the orphans with the understanding that this was a temporary duty pending the ability of the Sisters of Charity to assume this role and thus eventually releasing the Sacred Heart Sisters to perform their usual function — the operation of a private academy. Mother Ely of the Sisters of Charity told the bishop that she could not offer the services of her sisters. However, Mother Ely tempered her response by permitting Connolly to address the novitiate with the idea that those who volunteered to join him in the Diocese of Saint John would be separating from the New York group and forming a nucleus for a Saint John based congregation. Connolly gained four volunteers. Among them was Honoria Conway who would later be recognized as co-foundress of the Sisters of Charity of Saint John.8

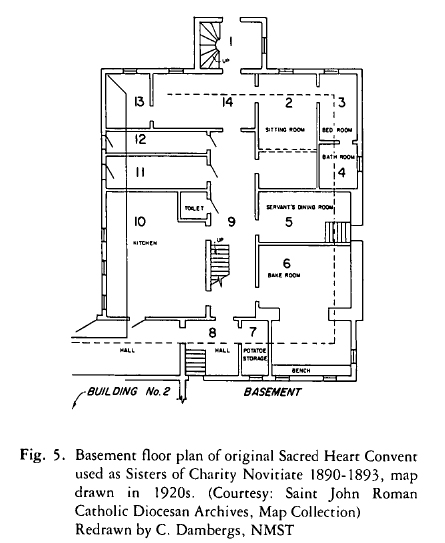

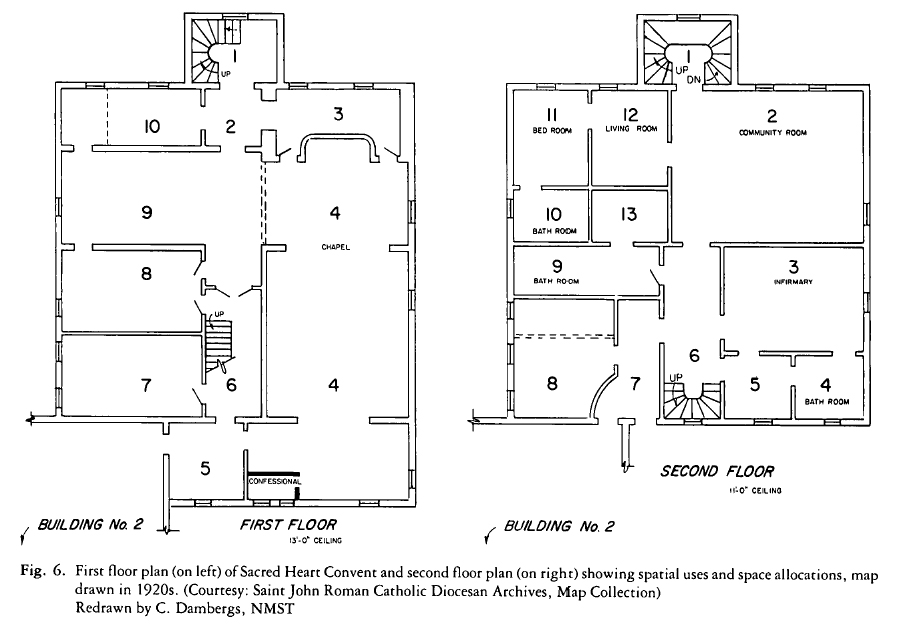

8 By the fall of 1854 Bishop Connolly had in place the sisters who would shortly set up an exclusive private girls' academy, but more important with respect to the range of services needed in the diocese, he had acquired a small group of novices pledged to the foundation of the Sisters of Charity of Saint John. Within months this congregation had taken over direction of the orphanage, thus allowing the Sacred Heart sisters to begin their academy. Additionally, the Sisters of Charity established a novitiate, and by late 1854 two recruits had arrived from New York. In 1855 two women entered from Halifax and in that year also came the first entrant from Saint John.9

9 For the Saint John Catholic community, which the Sisters of Charity served, these nuns provided the staffing infrastructure necessary for the Church to operate its system of social services. For the Catholic young women, largely from New Brunswick, who entered the Sisters of Charity, this religious institute held out the promise of a career alternative to marriage.10

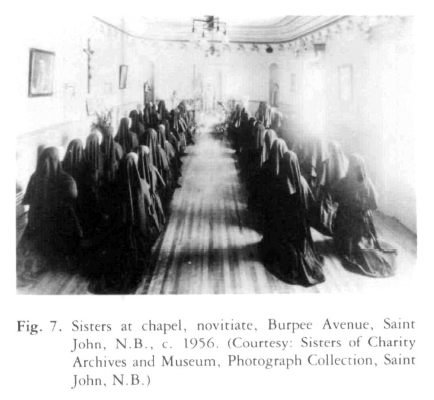

10 The Sisters of Charity was an apostolic community; that is, its members' lives functioned through two organizational dimensions: the prayer life, with its overtones of monasticism, and the areas of service which mirrored the secular spheres of nursing, teaching and social work. The prayer life originated in the medieval cloistered communities, where entrants took vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, lived according to the Rule of Silence and followed carefully prescribed schedules for prayer and other community activities. The areas of service derived from the actual pastoral work to be done. For example, for the Sisters of Charity this included running the orphanage and operating schools. The areas of service were essentially the "public face" of a sister's religious life. The prayer life was essentially the "private face," but it was ultimately more important because it was within this dimension that an interior life with God was encouraged, enhanced and strengthened.

11 The following discussion focuses on the material history of convent development in the Diocese of Saint John and as such reveals much of the prayer life and areas of service of an apostolic women's religious community.

A Material Legacy

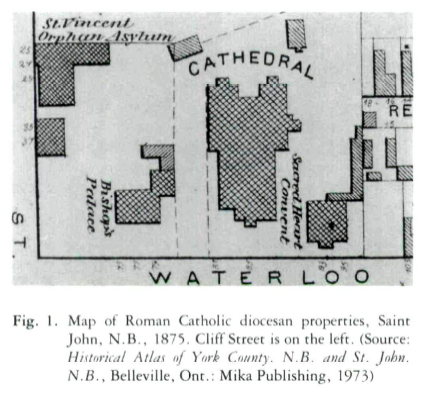

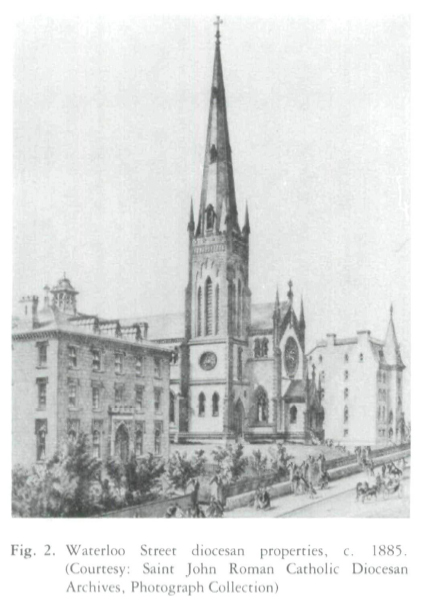

12 A map of the principal diocesan properties in 1875 (fig. 1) locates the bishop's residence and diocesan offices, the cathedral, Sacred Heart Convent, which fronted on Waterloo Street, and St. Vincent's Orphan Asylum, situated on Cliff Street. These edifices were conveniently located near a substantial Catholic community. The location of the two religious communities — the Sisters of the Sacred Heart with their academy for the well-to-do on Waterloo Street and the Sisters of Charity in charge of the orphan asylum on a side street — reflects the different classes served by the Church and is perhaps a striking spatial statement on how the Church approached and dealt with social order. Even an official photograph (fig. 2) of the Diocese of Saint John, which included the cathedral and the bishop's residence, also showed the Sacred Heart boarding school because it was located next to the cathedral. Essentially the photograph captured the diocese's best material "face."

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

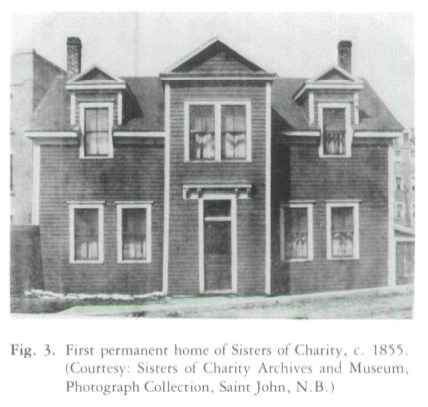

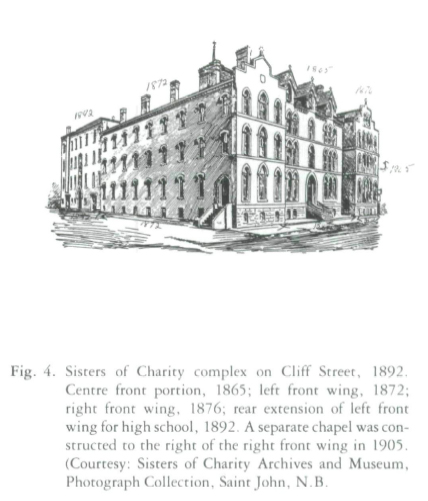

Display large image of Figure 213 The first permanent home (fig. 3) of the Sisters of Charity housed the nucleus of the community — Mother Conway, the other sisters, new entrants and orphans. The areas of service provided by the Sisters of Charity grew quickly during the 1860s to 1880s. By 1892, as figure 4 reveals, an imposing complex on Cliff Street contained the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Charity, accommodations for the professed sisters, the novitiate until 1890, the orphanage, the elementary school, and finally the high school. One function of having the sites of the prayer life and areas of service located in such proximity was the temporary adjustment in the early years to waive the one-year isolation generally imposed on novices and instead assign the novices to assist in the care of the orphans.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 614 As the Sisters of Charity expanded the need for a larger community chapel resulted in the construction of a separate chapel building adjacent to the Cliff Street complex. This chapel was planned by Mother M. Philomene Cyr (the only Acadian ever to become mother general) and completed by Mother M. Thomas O'Brien. The addition of the chapel in 1905, one year before the community opened its convents in the Canadian West, reflects not only the growth of the community but a further spatial refining of the distinction between the sisters' areas of service and the overtones of the structure of monasticism which were associated with the community's prayer life.

15 Just as the chapel suggested the internal focus of a sister's life, the uses of space within a convent reflected aspects of the religious life. Although floor plans for the Sisters of Charity Cliff Street complex do not exist, such documents are available for the Sacred Heart Convent, which was used as a novitiate house by the Sisters of Chanty between 1890 and 1893. The plans outlined in figures 5 and 6 were drawn in the 1920s when plumbing and heating systems were being installed, but barring the addition of these modern conveniences, the basic outlines of the principal rooms remained as they had been when constructed sixty years earlier. Not surprisingly, the floor plan is quite similar to that of the original 1865 St. Vincent Cliff Street convent which is still in use. As figure 5 illustrates, the kitchen, bake room and food storage rooms were located in the basement. What is labelled the servants dining room on this plan of the 1920s was in all likelihood a small refectory (dining room in religious houses). Location of these rooms in the basement, and therefore accessible only to the sisters who would attend to such tasks in silence, is another example of the structures of monasticism which defined spatial use and reflected the prayer life dimension of religious life.

16 Figure 6 outlines the uses of the first and second floors. The chapel and parlour rooms were located on the first floor. The chapel occupied the largest area because it was the spatial focus of the most important dimension of community prayer life, the Mass and adoration of Christ present in the Blessed Sacrament. The second floor contained the community room used by the sisters in the evening for group recreation, reading, conversation and games. Sisters did not have private rooms unless such were needed, for example in case of illness. Generally, only the mother general and the mistress of novices had a private room and this afforded them privacy when speaking with or instructing a sister.

17 The uses of some of the areas shown in figures 5 and 6 may be illustrated through a photograph collection made in the 1950s, when the Sisters of Charity Novitiate House was located at the Burpee Avenue convent. The interior of the Burpee Avenue chapel shows novices at prayer (fig. 7). At chapel the sisters would gather for morning prayers (5:20 a.m. - 6:10 a.m.) and Mass (6:30 a.m. - 7:00 a.m.) and in the evening for prayers (6:00 p.m. - 6:45 p.m.) and for night prayers (8:00 p.m. - 8:30 p.m.). A sister's individual visit to chapel, rosary, and office would also be completed some time during the day at her convenience. The chapel and virtually every room in the convent would contain a crucifix. It was the symbol of prayer life and the focus of service. Among the statues present in most convent chapels before the late 1960s and early 1970s would be that of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Devotion to Christ through His mother was common, and in a sense the purity personified in the Blessed Virgin Mary was emulated in religious life through the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

18 No chapel in a Sisters of Charity convent would be complete without a statue of St. Vincent de Paul. This saint is recognized by many church scholars as the pivotal of modern Christian humanitarianism; from his early seventeenth-century activities came the inspiration to found the Daughters of Charity and the numerous congregations of Sisters of Charity. In essence Vincent de Pauls Daughters of Charity foundations established the course for all other apostolic religious women's communities. In St. Vincent's words their convent was to be "the sickroom" and their cloister "the streets of the city." St. Vincent de Paul combined a prayer life and service to others in his work — a Christian message plus social welfare.11

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

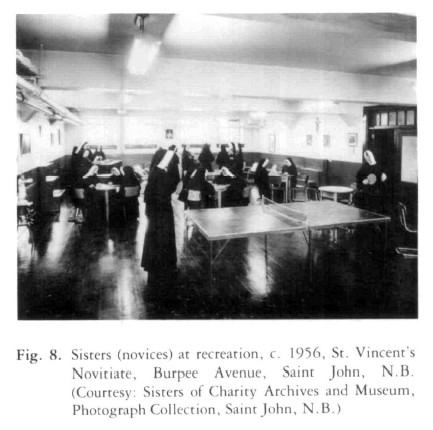

Display large image of Figure 819 As figure 8 indicates, the community room too contained a crucifix and pictures of Christ and various saints. Sisters recreated here as a group each evening. Group recreation was another way of collective living that tended to suppress individuality. In general, however, and perhaps reflecting the group nature of the activities that occurred in these rooms, the colour of the walls in the chapel and in the community room was much less austere than in the sleeping quarters.12

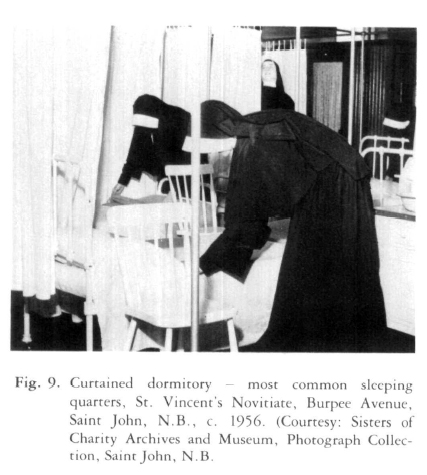

20 The curtained dormitory was the commonly used sleeping quarters (fig. 9). A sister's bedroom was very small because little time was spent there. It was used only for sleeping, morning bathing and private night prayers. The bedroom would typically contain a crucifix, holy water font, kneeler with prayer books and missal, a desk and a chair. Sleeping quarters contained only one chair, as visiting in these areas did not usually occur.

21 In addition to the exteriors and interiors of convent buildings, which graphically reveal the overtones of monastic life integral to religious life, a sample of the reading material from the library of the original Sisters of Charity community room at Cliff Street underscores a preoccupation with questions of the soul, contemplation and the role of the Sisters of Charity.13 In short, the reading matter reinforced the dual dimensions of the apostolic community: prayer life and areas of service.

Display large image of Figure 9

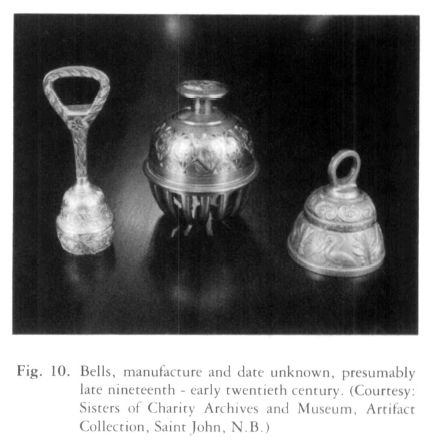

Display large image of Figure 922 Perhaps no object quite captures the essence of the overtones of monasticism and the routine of convent life more succinctly than the bell. (fig. 10). The bell was the symbol of collective discipline and a pattern of ordered activity. In the morning, the bell broke silence as it called a sister from sleep, signalled the start of prayers, announced the consecration of the Eucharist, invited a sister to breakfast, and bid farewell at the start of daily activities. In the evening, it summoned a sister to supper, welcomed her to the evening Angelus, beckoned her to community recreation, accompanied her to night prayers and meditation, and finally at 8:30 p.m. imposed the Great Silence which lasted until the next morning at 5:00 a.m., when once again the bell broke silence.

Display large image of Figure 10

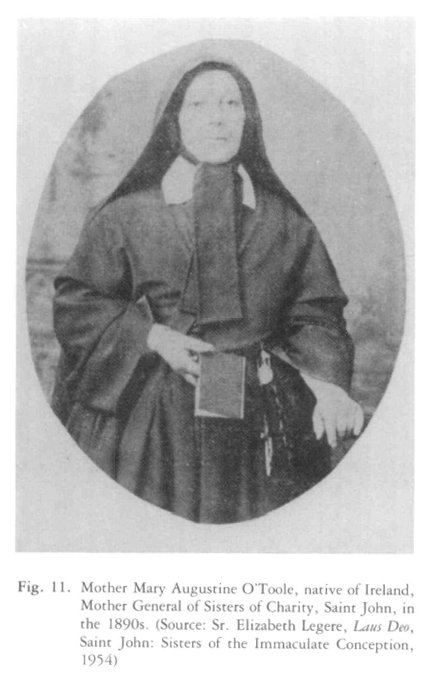

Display large image of Figure 1023 Although the bell might be identified by many as representing the ordered structure of religious life, for most in the secular world, the habit would be most synonymous with convent life. In figure 11 Mother Mary Augustine O'Toole is wearing the habit used by the Sisters of Charity between 1854 to 1905. The habit consisted of a one piece black dress, a pleated apron, and a short bodice cape. At the neck was affixed a removable white collar and at the wrists, removable white cuffs. A belt encircled the waist and from it was suspended a large set of rosary beads. The headdress consisted of a band across the upper forehead, a head covering over that, which tied under the chin, and a veil that was pinned to the head covering. The veil was intended to block peripheral vision so that a sister's eyes would not wander from the task at hand. In most religious communities this was supposed to assist in keeping "custody of the eyes."14

24 The purpose of these habits was to further diminish the perception of individuality among community members, and it was part of the standardization necessary for a collective life. Diminishing the importance of dress through the use of a "uniform" was in itself a discipline. The habits of religious communities underscored the monastic dimension of the life by symbolically subsuming the individual within the community uniform.

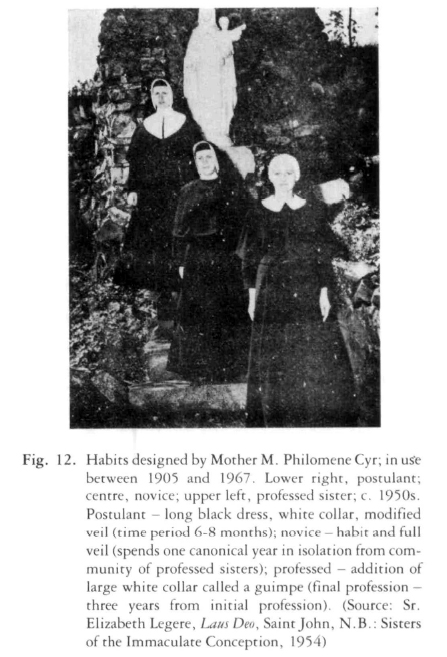

25 It is difficult to determine precisely what led the Sisters of Charity in Saint John to adopt their particular religious habit. There is an obvious contrast between the Saint John habit and the "bonnet" style veil worn by Mother Seton's Sisters of Charity in New York. The contrasting veils raise some interesting questions. Although Mother Conway had been in the New York novitiate, upon returning to Saint John the heavier looking veil was adopted. There does not appear to be any recorded explanation, though it is possible to speculate. The Saint John habit is somewhat reminiscent of the Sisters of Mercy habit used in Ireland at that time and also similar to a habit utilized by Mother Frances Cabrini's Italian sisters, the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Quite possibly Bishop Connolly and Mother Conway, both natives of Ireland, might have settled upon the European religious habit, decidedly more austere than the American version. In 1905 Mother Mary Philomene Cyr redesigned the habit worn by the Sisters of Charity of Saint John. The new habit (fig. 12) with its variations for postulants and novices was used until 1967.

Display large image of Figure 11

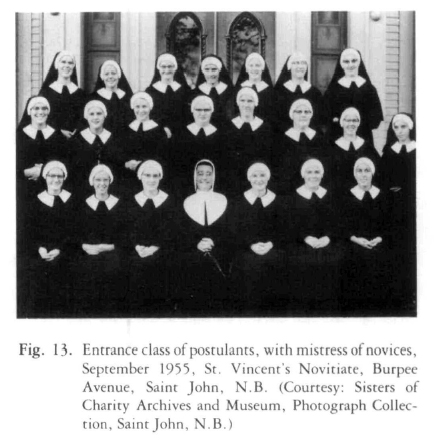

Display large image of Figure 1126 With the exception of those sisters who occupied the position of mother general, sisters were almost always photographed in groups. Pictured in figure 13 is a class of postulants photographed either on entrance day or a week later. Shown also is the mistress of novices, that is, the sister responsible for the socialization of new recruits into the religious life. Although it is commonplace to speak of the changes in religious life occurring after Vatican Ⅱ, this picture was taken in 1955, seven years before Vatican II opened; thus it suggests a diminishing of the structures of monasticism in an apostolic community.

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 1327 The further evolution of that process was accelerated by Vatican Ⅱ and demonstrated in the new habit in 1967. It featured a long black skirt with a white blouse and short waist jacket. The long rosary beads were no longer a part of the religious dress. A simplified and less austere veil also revealed the hairline of an individual. By the late 1960s the religious habit had begun to reflect some of the more fundamental changes occurring in religious life.

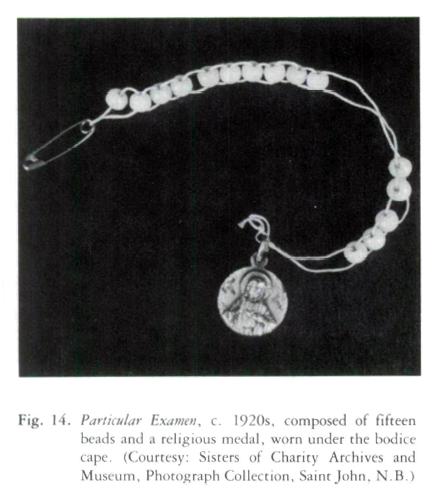

28 While most of the preceding has dealt with the overtones of monasticism which emphasized the collective life of sisters, one object which highlights individual responsibility was the particular examen (fig. 14). In most convents private night prayers included the examen, essentially an examination of conscience through a series of questions, for example — "was I tolerant today?" or "was I kind toward?" The particular examen, on the other hand, charged an individual with the obligation of working on a particular dimension of her personal development. Usually the mistress of novices would have noted some area that could be improved, such as developing more patience when working with others. Through the day, the novice would move a bead downward if upon reflection a situation could have been handled with a greater degree of patience. At the end of the day the position of the beads indicated one's success or failure. Despite the standardization, discipline and collectivism of convent life, as an object the particular examen most clearly underscored the community's recognition of the individual's personal responsibility for the development of an interior life.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14Concluding Observations

29 Vincent de Paul had wanted his Daughters of Charity and eventually their successor communities to be active in areas of service, not isolated in a cloister. This goal was reiterated in his directive that their cloister was to be "the streets of the city." However, even though the cloister was rejected as a model for his Daughters of Charity, the act of establishing a community of women having a connection with the Church, while ensuring a coherent organizational basis, resulted in some borrowing from the monastic cloistered communities. Thus, from the beginning an organizational tension was present in the life of apostolic communities that was caused by their dual priorities: the prayer life and the areas of service.

30 On at least one occasion that has been documented Mother Conway dealt with the consequences of that tension in 1855 when the novices were dispensed from the isolation of the novitiate to work with the orphans. As this instance indicates, the formal requirements of the prayer life did not impede the pressing immediacy of service.

31 Undoubtedly there were other occasional, however temporary, intrusions upon the prayer life in response to specific service needs. Nevertheless, despite the obvious commitment of the Sisters of Charity to teaching, nursing and social work, it was the prayer life which separated the sisters from their secular counterparts engaged in similar activities.

32 Thus, not surprisingly, this paper in focusing upon the material legacy of the convent has been concerned almost exclusively with the artifacts of the prayer life: the spatial uses and interior decor of convent buildings, the religious habit and specific convent objects. Despite the apparent willingness of the sisters to occasionally dispense with the requirements of the prayer life, these objects symbolize the essence of what separated those in religious life from those in the secular realm. As well, they underscore the tension within apostolic communities committed to service and to prayer.

33 Possibly this tension is no more clearly illustrated than in the attempts of religious institutes to comply with Pius Ⅻ's directive that members of apostolic communities become better educated, thus improving their abilities to provide these services. In the course of this effort, much from the externals of the prayer life receded in importance. These artifacts, now relegated to museums, serve today as a poignant material legacy of a Catholic religious social organization that once functioned as a compelling career route for women.

I am indebted especially to Sister Marion Murray, Sister Rita Keenan and Sister Bertha Marcoux of the Sisters of Charity of the Immaculate Conception, Saint John, N.B. Peter McGahan of the University of New Brunswick-Saint John also made several helpful suggestions.

An earlier draft of this paper was presented in September 1986 at the Atlantic Canada Workshop, Fredericton, N.B.