Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Observations on Figures, Human and Divine, on Nineteenth-Century Ontario Gravestones

1 Nineteenth-century Ontario gravestone carvers satisfied the needs of their customers with a relatively limited number of designs on the stones they provided. Evidence from remaining stones indicates that willows and urns, hands, bouquets, lambs, birds and flower buds were the preferred decorations of the period. Gravestones with representations of human or winged figures are found infrequently in these early cemeteries. Assuming there is no selection bias in the type of stone remaining above ground, we have found that only about ten per cent of early Upper Canadian cemeteries contain any stones depicting a human or angelic figure.

2 Interestingly, the stylistic preference in eighteenth-century New England and Nova Scotia was just the opposite. Representations of human or human-like faces appear on a majority of the stones of this period, and richly carved full figures are not unusual. Many of these early figures are "soul effigies" — curious faces in which a primitive skull or face is flanked by outstretched wings.1 Some of these later developed into highly abstract designs, although more commonly one finds obvious angel faces or actual portraits of the deceased.2 The more elaborate East Coast stones include full figures — Adam and Eve, angels blowing trumpets, classically draped females, and men and women stylishly dressed in the latest fashion. The designs, which may first have been intended as grim reminders of death, developed into what to us look like rollicking cherubs and elegant society portraits. However, toward the end of the eighteenth century, an enthusiasm for the classical past caused gravestone designers to turn to willows, urns, monuments and columns. This development coincided with the early settlement of Ontario and may be one reason for the rarity of human figures on early provincial gravestones.

3 Some stones in Ontario cemeteries were clearly cut by professional carvers. They date from the classical revival period of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and were almost certainly imported from the United States. The designs, most frequently willows and urns, show clear affinity with stones of the same period from upper New York State, and some are signed by New York carvers. These stones are particularly numerous in the Niagara Peninsula. However, many stones from early nineteenth-century Ontario were presumably locally cut. They look quite different from the American style, in that most are crudely cut, and few have any decoration. Judging from the dates of these stones, sometime in the 1830s local workshops were established and began to produce what we have come to recognize as distinctly Ontario stones.3 The willow was the most common design, with or without urns, closely followed in popularity by pointing or shaking hands. A little later, bouquets and blossoms began to appear, as did birds and lambs. Types of designs tended to be similar, yet details were varied: hundreds of willows drooping over urns were carved, but each was slightly different even when clearly carved by the same person. One surmises that although pattern books were no doubt available,4 most designs were transferred onto the stone free-hand.

4 A small number of gravestones carved between the 1830s and 1880s had representations of either human or angelic figures. All differ markedly from one another, and show greater variation in style than seen with the common designs. The skill of the carver ranged from very limited to highly competent, and therefore while some stones are fine and moving works of art, many appear humorous and even ludicrous to modern eyes. Frequently the figures are awkward, stiff, or distorted, and seem uncomfortably squeezed into an otherwise conventional design.

5 For the purposes of our study we have divided these nineteenth-century Ontario gravestones which feature figures as part of the design into two groups - human and divine. "Human" refers to stones with figures clearly meant to represent persons, although they are not necessarily portraits. "Divine" refers to stones with winged figures, allegorical figures, or rarely, representations of the divinity. The stones are variously located in cemeteries from Lambeth to Prescott and bear death dates from 1835 to 1885. More than one-half of the stones are signed, unusual in a time when very few stones have any indication of carver or place of origin.

Human Figures

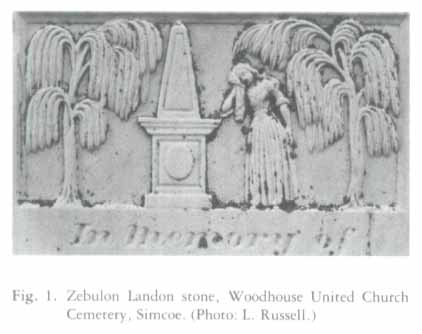

6 The mosty frequently seen human form on early Ontario gravestones is the mourning female figure. Although most of the stones are worn and facial details are lost, it seems that while some were meant to represent actual persons, most appear to be general representations of the sorrow felt by the bereaved. The figure is either draped in classical style or dressed in contemporary clothing. She is often shown leaning, kneeling or crouching over a tomb or monument, head bowed, face buried in her hands or a large handkerchief. Often, drooping willows overhang the monument, and the human figure serves as only one aspect of the design. The Zebulon Landon stone (d. 1839) is a good example of the mourning female figure (fig. 1). The white marble was skillfully cut and is still in good condition. The mourner's face is youthful, and her contemporary gown retains its fashionable details.

7 In other examples the carver has not relied on the conventional willow and monument to set the scene. Occasionally, the mourner bends over a broken column, and in one case, the McFarland Wilson stone (d. 1851) in St. John's Anglican Church cemetery, Simcoe, a winged figure holding a scythe stands behind the mourner, a consoling hand placed upon her shoulder. In our experience this stone is unique in Ontario, but a very similar design can be found on a stone in Worthington, Ohio.5 This, as well as other examples we have seen of similarity between Ontario and American stones, indicates considerable influence of American carvers on local craftsmen — either through immigration or more casual contact.

Display large image of Figure 1

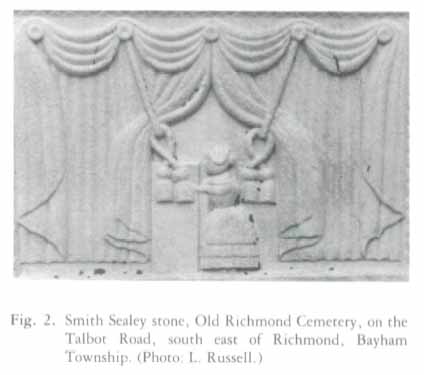

Display large image of Figure 18 The Smith Sealey stone (d. 1845), signed by B. Hicks of Brantford, is an example of a local stone of unusual design (fig. 2). A crudely cut, fat figure stands before a large block of stone, presumably a monument. Both are overwhelmed by great curtains partly tied back by cords with enormous tassels. The effect seems bizarre.

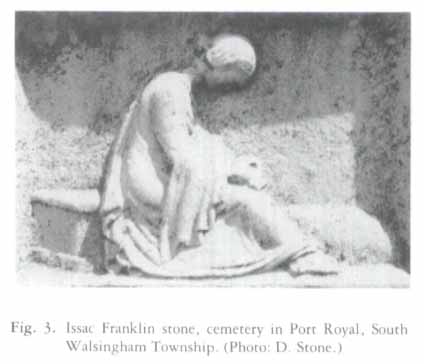

9 In complete contrast to the Hicks stone is the work of Samuel Gardner, a sculptor by training.6 Gardner worked in the Simcoe and Hamilton areas in the mid-nineteenth century. His technical skill and sense of design were unequalled in Ontario gravestone art. He was clearly at ease in carving human figures, and he produced a significant number of stones displaying human and allegorical figures. We have located five stones with mourning female figures which either were signed by Gardner or are stylistically his work. He, too, frequently places his mourner in a scene with the conventional willow and monument, but his figures always dominate the design. In perhaps his finest remaining carving, a signed memorial for Issac Franklin (d. 1858), Gardner simply placed his seated mourner on a slightly raised tomb (fig. 3). Though the marble is worn, the figure in her slightly abstract state is a beautiful and moving symbol of grief and resignation.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

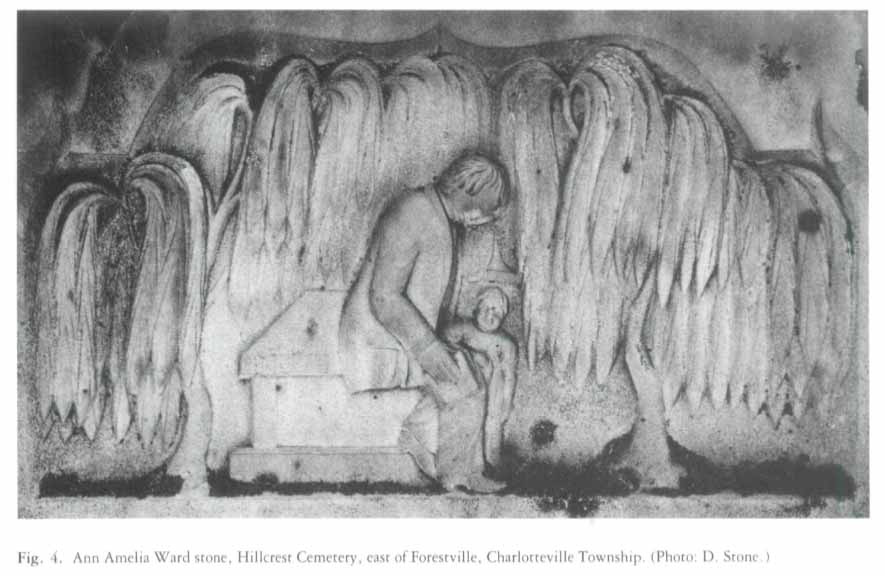

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 410 The male mourning figure is seen much less frequently on Ontario gravestones. Our collection contains only seven examples, two of which were carved by Samuel Gardner. His monument cut in sandstone for Ann Amelia Ward (d. 1852) shows a male figure carved in fine detail (fig. 4). The figure is almost engulfed by the pair of willows which crowd around the tomb, and the sense of oppression is heightened by a curving frame which seems to force the willows to bend even lower. Gardner has succeeded here in using conventional gravestone symbols to intensify the emotional effect.

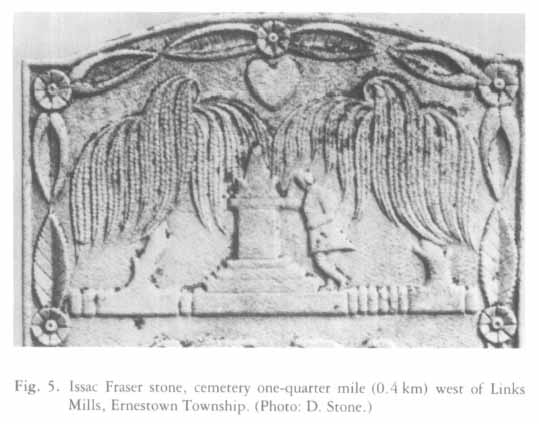

11 Other examples with male mourning figures are not so effective. The mourners are stiff and the number and exuberance of symbols worked into the design are excessive. The Betsy Yorke stone (d. 1864) in Plains Cemetery east of Union, Yarmouth Township, signed by J . W . Smyth, is an example. It has an all-seeing eye, a pair of clasped hands, a willow, a monument and a small male mourning figure. In the upper corners of the stone are huge curling leaves, and the text is surrounded by an ornate border. The figure, right hand clasping his forehead, the left holding a hat, is almost lost in the welter of detail. Somewhat more successful is the Issac Fraser memorial (d. 1858). Again the carver, possibly Higgins of Kingston, has crammed considerable detail onto the marble, but the elements are relatively well balanced (fig. 5). Nevertheless, the mourner is but a small part of the total design.

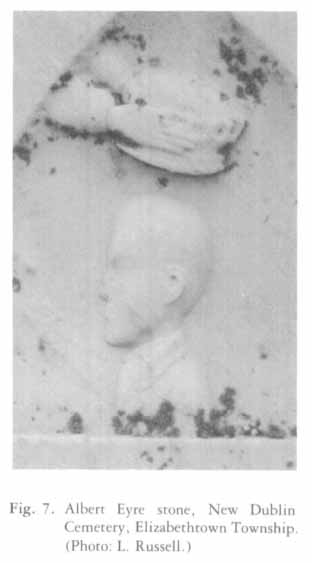

12 A few Ontario stones have human figures that are not mourners. In addition to several Orangeist stones with horse and rider, there are scenes commemorating the deceased's profession or an event in his life. In Trinity Anglican Church cemetery, Lambeth, a stone carved by Hooper and Thompson of London shows a fireman standing beside his belching engine. Thomas Deazeley (d. 1854), professor of surgery, appears to be standing at his lecturn on a dias, hand raised to emphasize a point in his oration (fig. 6). The facial features are worn, yet the portly figure still has considerable individuality and may be a portrait carved by Hurd of Toronto. The Albert Eyre stone (d. 1885) by Williamson of Gananoque may also have been intended as a portrait (fig. 7). Though the man's head is curiously elongated, the details of his clothing and his features are well-defined. Above the head a pair of hands holds what looks like a ceremonial hat or crown, perhaps commemorating an event in the deceased's life.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

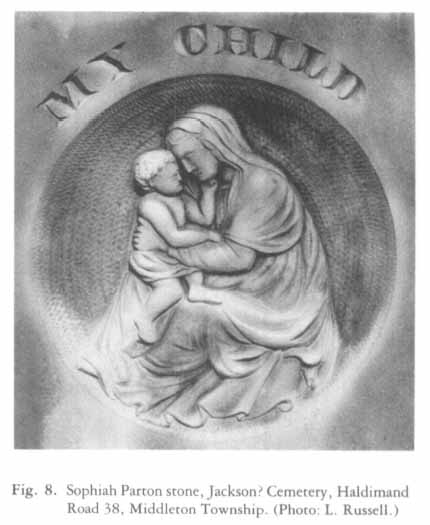

Display large image of Figure 813 Depictions of a mother and child are surprisingly rare. We have only seen four examples, two carved by Samuel Gardner. He was evidently influenced by European styles, since the similarity to famous madonna and child paintings is inescapable. The sandstone monument to Sophiah Parton (d. 1864) again demonstrates Gardner's control of his material and his attention to anatomical detail (fig. 8). Very seldom is a child represented on a gravestone. Most children's stones show lambs, broken buds, or birds. Of the three examples in our collection, two appear to be figures of an idealized child. However, the marble stone erected to the memory of Mary Lee (d. 1868) was carved with skill and sensitivity by an unknown craftsman (fig. 9). The details of hair, face and clothing suggest that this could have been a portrait stone.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9Divine Figures

14 In this category we have grouped figures with wings, allegorical beings and the occasional depiction of the divinity.

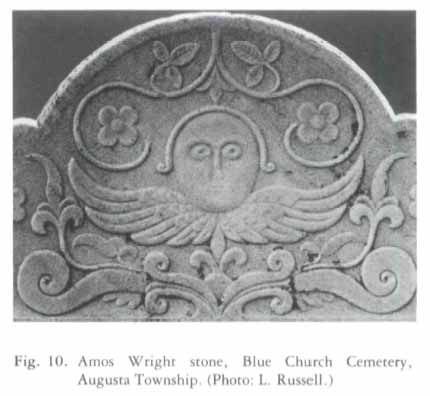

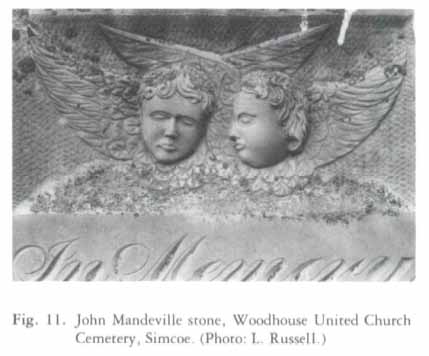

15 In contrast to the number of soul effigies found in East Coast cemeteries, we have seen only one in an Ontario graveyard. However, this stone (fig. 10), to Amos Wright (d. 1796), was almost certainly by the Connecticut carver Zerubbabel Collins, whose work is well-known to scholars of New England gravestone history.7 There are a number of later, locally carved stones depicting cherubic faces flanked by wings. The ancestry of these little angels may be the putti which were so popular in European art of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They appear as well on New England gravestones of the same period.8 The Ontario cherubs appear singly, in pairs and even as trios, in designs ranging from the starkly simple to highly ornate creations with surrounding flowers and leaves. A fine example by Samuel Gardner stands in the Woodhouse United Church cemetery, Simcoe (fig. 11).

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

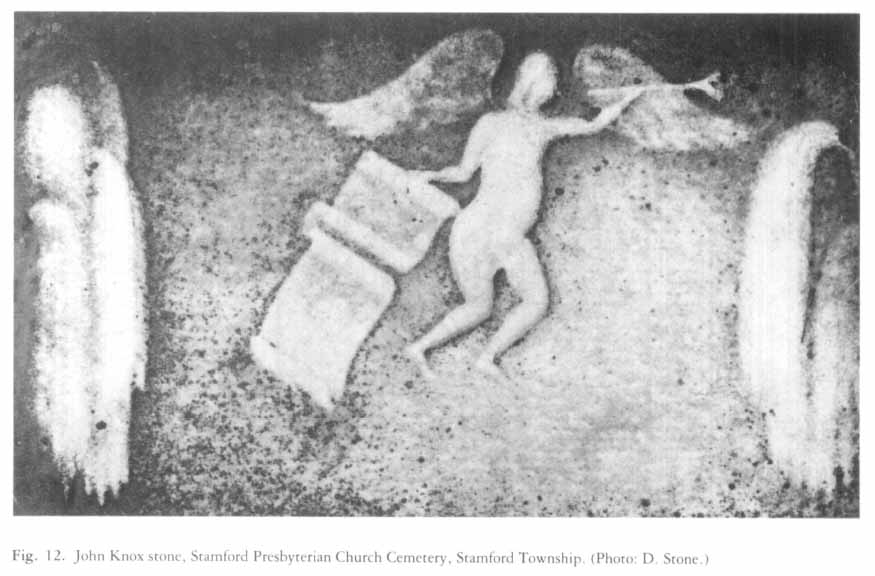

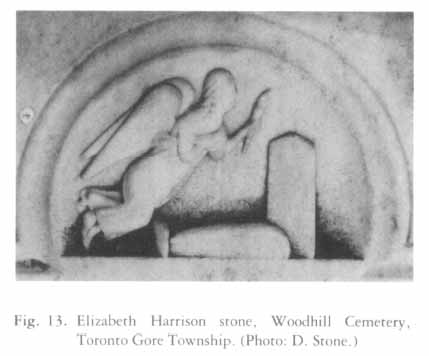

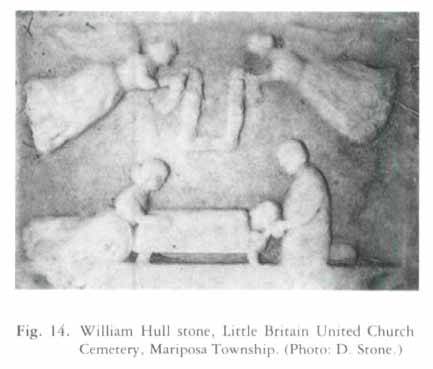

Display large image of Figure 1316 Full-figured angels provide a wide range of designs and seem nearly as popular as mourning female figures. It seems that carvers freely exercised their imaginations in carving these figures, sometimes with what we might consider humorous results. The John Knox stone (d. 1842) shows an obese, strangely proportioned angel ascending between a pair of willows. One hand holds the trumpet of doom to its lips, the other trails a scroll (fig. 12). This benign figure seems to suggest, perhaps unwittingly, that doomsday will not be a terrifying experience. Although this angel is naked, most we have seen are clothed, and as Frederick Burgess points out in his study of English gravestones, "the dress of angels is an amusing study."9 For instance, the angel on the Elizabeth Harrison stone (d. 1855), carved by Hurd of Toronto, hovers over the deceased's tomb holding a torch in one hand and clutching the top of its immodest gown with the other (fig. 13). On other stones angels appear in flowing classical dress, and some wear what Burgess describes as "Victorian nightgowns." In addition to scrolls and trumpets, angels carry wreaths, anchors and other symbols of death and immortality. On one particularly poignant stone to young William Hull (el. 1866), two angels hover over the bier with what could be a winding sheet held between them (fig. 14).

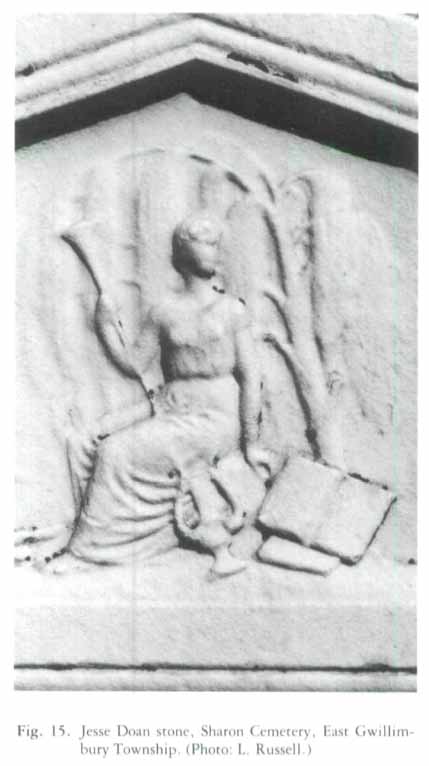

17 Allegorical figures are uncommon in Ontario designs, although some of the mourning female figures might be included in this category. The Jesse Doan monument (d. 1868) appears to be an example of the use of classical imagery (fig. 15). The woman with her horn, book and lyre may represent the departed's interest in music, appropriate symbolism for a member of the Children of Peace.10 In other instances it is not clear what, or who, the figure is intended to represent. The figures are usually dressed in flowing garments, but have no wings or other characteristics of angels.

18 With the exception of crucifixion scenes, we have seen only two depictions of the divinity. In St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church cemetery in Kingston, the stone to William Horan (d. 1851) has a medallion with a mother and child. Both figures wear lopsided halos, and presumably represent Mary and Jesus. The Peter Richard stone (d. 1858) in Locust Hill cemetery, Markham Township, is an unusual representation of Christ. The Christ figure is seated, with the right hand raised in benediction, while the left hand rests on a small head. Clinging closely is another small figure. This may be an illustration of "Suffer the little children to come unto me."

19 It is interesting to speculate on the reason for the relative rarity of stones depicting human or divine forms. Possibly the early Ontario stone carver felt uncomfortable with the difficulty of carving the human figure. The crudity of some of the examples lends credence to this theory. Possibly the customers preferred the more commonly used styles of willow, urn and flower, and rarely commissioned original designs. While all types of early gravestone carving are worthy of preservation as examples of folk art, the styles described herein are particularly valuable for providing an intimate glimpse of the thought and taste of the period.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14 Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15