Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Thomas Nisbet's Furniture:

Distinctive Style, Design and Workmanship*

1 Thomas Nisbet of Saint John, New Brunswick, is the only early British North American cabinetmaker whose labelled pieces of furniture exist in large numbers. These historically documented examples are very important in that they provide distinguishing characteristics which can be used to identify unlabelled furniture made in Nisbet's workshop. They also contain evidence of the styles and materials used, as well as the workmanship of this cabinet-maker.1 This system of using characteristics, while applicable to Nisbet, can, by extension, be used to identify the work of other cabinetmakers.

2 Nisbet, who was active in Saint John between 1812 and 1848, used two labels.2 The first, "Thos. Nisbet, Cabinetmaker & Upholsterer, Prince William Street, Saint John, New Brunswick, ..." was in use until 1834 when he took his oldest son, Thomas Jr., into partnership. After that he used the second label, "Thos. Nisbet & Son,...".3

3 The object characteristics discussed in this research report will apply to Nisbet's furniture made prior to 1834, since more labelled examples from this period have been available for study. An examination of his work from that time shows that it is very distinctive and possesses characteristics, which in combination, render it nearly unmistakable. In analyzing a number of his pieces as a group, there is an evident harmony and consistency in style, design and workmanship. Although Nisbet hired many journeyman cabinetmakers and had apprentices working under him, he maintained a uniformity of technique in workmanship and construction.4

4 He was influenced by the prevailing designs in England and the United States of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. His work falls within the Hepplewhite, Sheraton, Classical Revival and Regency styles although his later work, with the label "Thos. Nisbet & Son," is American Empire. Many of his pieces combined characteristics of two or more, particularly Hepplewhite Sheraton, Sheraton-Classical Revival and Classical Revival-Regency, but his furniture is marked by a very personal quality distinguishing it as being his own. A number of earlier styles by Nisbet were used for furniture made well into the nineteenth century.

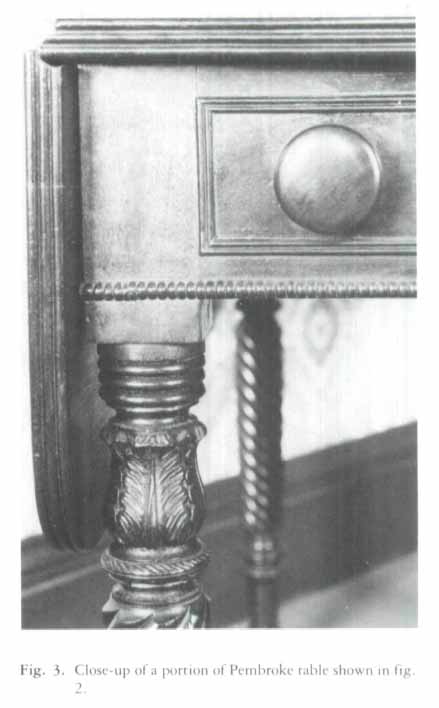

5 Let us now examine a few examples of Nisbet's furniture and determine some of the distinctive methods of treatment which may be considered as being indicative of his work. On the simple leg of a dropleaf, or Pembroke, table, for example (see fig. 1), two Nisbet characteristics can be seen. Each of the three large turned grooves are ebonized. Ebonizing is the staining or painting of the wood to resemble ebony. This technique was used on almost all of Nisbet's turned and carved work. The two-ring turnings on the base portion of the leg appear on many of his pieces.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

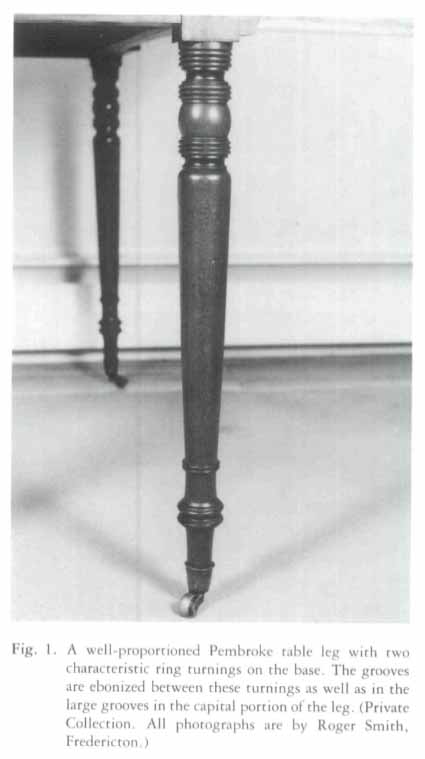

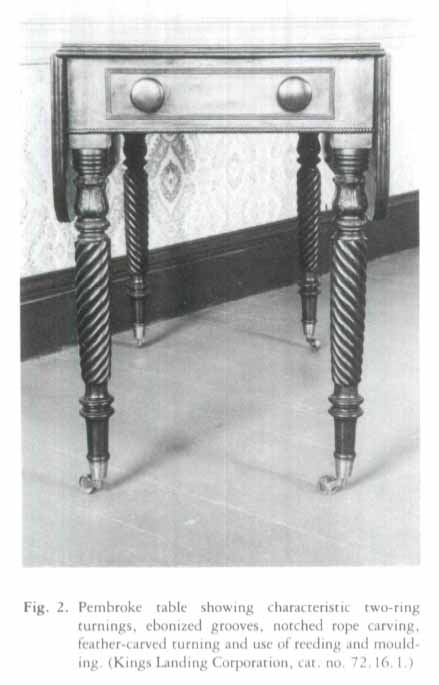

Display large image of Figure 26 A more elaborate Pembroke table shows ebonized grooves, two-ring turnings on the base of the leg, and the use of reeding and beaded moulding which was typical (fig. 2). Another important characteristic found on many of his turned and carved legs, columnettes, pedestals and sofa seat rails is the feather-carved turned ring on the capital portion of this table's leg (fig. 3).

7 Rope-carved legs (fig. 2) have often been used to attribute furniture to Nisbet. Caution should be used in considering this characteristic alone as it is not a very valuable criterion. Nisbet advertised extensively that his workshop would do piecework turning and carving for customers, and they would have been primarily contemporary cabinetmakers.5 Rope carving should certainly be taken into consideration, but in conjunction with other distinctive Nisbet characteristics. Note, too, that Nisbet's rope-carved legs usually have each strand ol tin rope notched at the upper end (fig. 3).

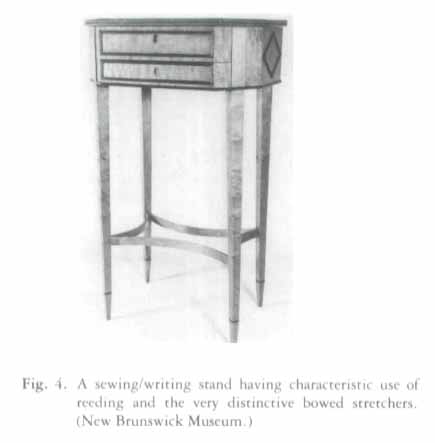

8 Notching was also used at the end of much of his reeding on legs and panels. He employed reeding to emphasize or supply delicacy of structural lines, whether vertical, horizontal or to create effect. The use of reeding is well illustrated on the writing/sewing stand (fig. 4), where the edge of the top is reeded and two-reeded moulding was used to outline the drawers and to make decorative lozenges on the ends and back.

9 The delicate, bowed stretchers of this stand made of two laminated pieces are found on two labelled pieces. The same stretcher design is found on a sewing/writing table that was originally housed at the Winterthur Museum, but now is in the Canadiana Collection of the Royal Ontario Museum. The pointed double taper legs, which are characteristic of some American Federal furniture of the 1790-1820 period, have not been found on any other labelled Nisbet furniture.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

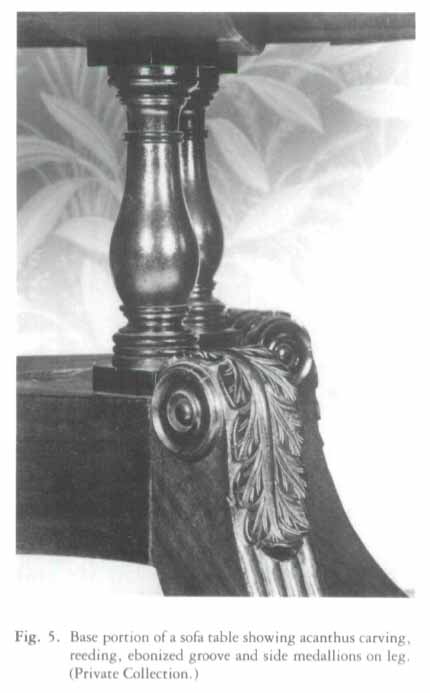

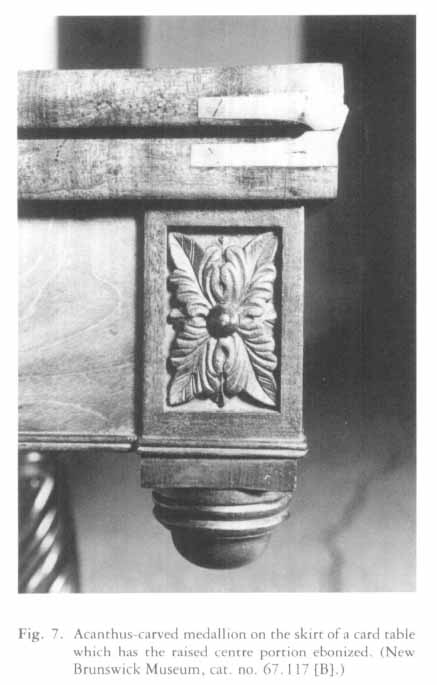

Display large image of Figure 610 Acanthus leaf carvings are distinguishing features, although there is variability in the way that the leaves are carved. This would relate to the fact that different turners and carvers were employed during the early period of his work.6 Nisbet used the acanthus on legs (figs. 3 and 5), pedestals, table columnettes (fig. 6), seat rails of sofas, bedposts and decorative panels (fig. 7).

11 Carved round medallions were characteristically put on the legs of Regency style pieces (figs. 5 and 6). If the knee was carved, these medallions were placed on each side of the knee. On legs that were not carved, a single medallion was attached on the front of the knee.

12 He employed distinctive construction for drawers. The bottom was finished or completely dressed showing no planing, saw or tool marks. It may be champhered and may have glue blocks. It was inserted into grooves in the sides, fitted into a groove cut into the bottom of the drawer front and nailed to the back of the drawer. Many times, strips of quarter round moulding were attached lengthwise, fastening the sides to drawer bottom.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 713 Nisbet's concern for a finished product is illustrated by the beaded moulding along the base of the table end (fig. 2). It extends around the corner blocks under the leaves in a continuous fashion. His mouldings almost always continue onto the less obvious parts of furniture, such as the backs of card tables that were placed against the wall. Also, he always veneered the top edge of his card tables with miscellaneous pieces of veneer which are normally covered by the top when the table is both open and closed.

14 The few examples described and shown here not only demonstrate that Nisbet's work is finely wrought, but that it possesses distinctive characteristics which appear consistently. However, just because a piece of furniture has a particular Nisbet characteristic, it does not automatically follow the piece was made by him. It is the various characteristics, in combination, which can be used to make an attribution.

*Dr. George MacBeath is gratefully acknowledged for his valued editorial assistance.