Reviews / Comptes rendus

Provincial Museum of Alberta, "Spiritual Life — Sacred Ritual"

1 It is the measure of the impact of this gallery that officials from one group should weep uncontrollably for ten minutes before finally gaining sufficient composure to express gratitude. Its potential is such that peoples whose friends and relatives kill each other half way around the world, should grasp each others hands in recognition of a common humanity. It should at the outset be plainly stated: this exhibition carries a symbolic meaning unusual for most galleries.

2 Perhaps some of this power derives from the way religion is characterized in official culture. Most people acknowledge the importance of the spiritual roots of their identity in some form, but officially Canada is secular. The ambiguous relationship of our cultural heritages to the identity of the country is reflected sometimes in a hesitancy to affirm just what these heritages are. Add to that the discord religion has fomented historically, and we have ample reason to downplay its role in the makeup of the nation.

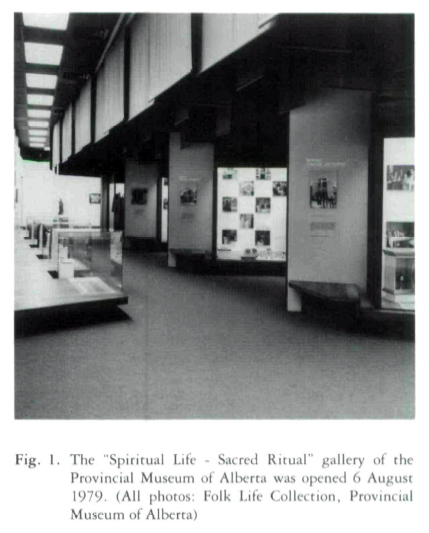

3 But ignoring reality deprives us all of truth, and invites confusion in our children. It is the conviction of "Spiritual Life — Sacred Ritual" that in the real life of the people, such ambiguities do not exist. Men and women are religious — sometimes in very complex, irregular ways. They participate in a tradition that brings depth and meaning at several levels of their existence, regardless of whether they live in Alberta or Romania, Edmonton or Moscow. This first permanent exhibition of the Provincial Museum of Alberta's Folk Life Program is a worthy expression of the purpose of that segment of human history: to collect, research and exhibit materials on the peoples of Alberta. The pertinent question is whether it adequately expresses either the complexity of religion or the diversity of the people.

4 On entering one notes a collection of sacred writings, examples from the vast number of scriptures from the religious world whose devotees are represented in the peoples of Alberta. Here is one indication of an attitude that prevails throughout — the holy words of each religion stand equally accepted and honoured, with brief segments translated as vignettes of the tradition. Wherever sacred words appear they are printed in red, with interpretive text in black. The planners have deliberately leveled distinctions of numbers and significance of groups in the province in the presentation of this material. This may be more than some believers from beyond our shores might have thought possible: it is certainly less than the much-vaunted "bible-belt" devotees would believe (or perhaps accept). This emphasis on the written text dominates the entire exhibit; it makes visits to the gallery much longer and more intensive than others. Thus considerable investment of time is needed to survey the collection.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 If sacred writings are used to introduce spiritual life, the main focus of that life is ritual. The curator has chosen two themes. The first is to detail the "life-cycle" rituals, utilizing rites from different religions to express a different moment in the birth-to-death rites de passage. Photos taken of a contemporary rite is juxtaposed to an iconic painting which represents the traditional image in the history of the group. This works sometimes, as in the traditional painting of the baptism of Jesus, used in conjunction with Mennonite baptism, but is lost in the Sikh marriage with a picture of Krishna (a Hindu deity) and his wife. In general, however, the iconic image is overpowered amid the photos of the contemporary rite and the interpretive text, so that one would have to have fairly sophisticated knowledge of the traditions to understand the relationship of the icon to the rite.

Display large image of Figure 2

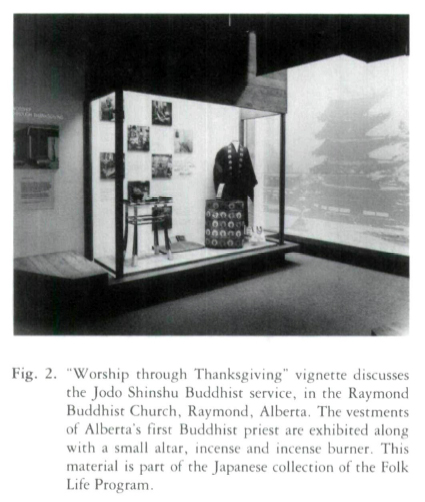

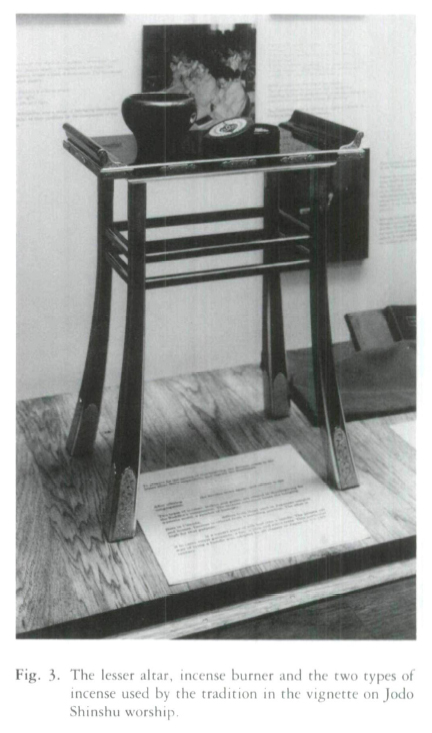

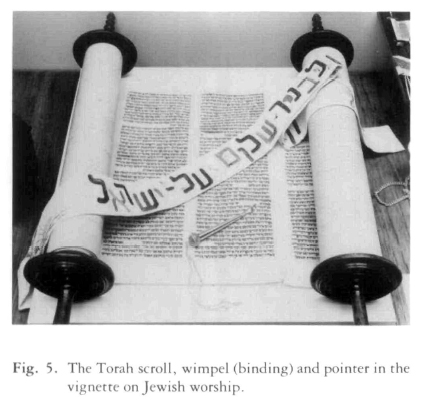

Display large image of Figure 26 The other focal point is worship. The items are arranged in eight standing displays set at angles to a backdrop of huge grey photographs of buildings representing the European or Oriental homeland of the tradition. Each display features the key ritual gestures of the prime act of worship for a tradition. This is not a festive ritual. It represents the ordinary, everyday ritual of worship that anyone from that tradition knows and participates in. By selecting this ritual, the curator is underlining the regular and commonplace interaction with the divine which constitutes the believer's religious world. Ritual vestments and artifacts flesh out the display. For example, the vestments of the first Jodo Shinshu priest to serve in Western Canada, Rev. I. Kawamura, include an ink-black kuroma, over which fits a thin stole called a wagesa. Finally, a large festive garment called a Gojo Gesa completes the ensemble. Along with the mannequin dressed with these garments, the display features a small "lesser" altar on which rests two types of incense, makko and ginko, which the devotee traditionally offers, as well as copies of the service books and juzu, prayer beads with 108 seeds of the bodhi tree. These beads represent the 108 passions which must be overcome.

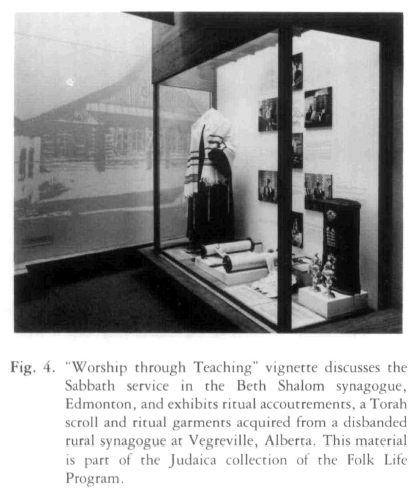

7 The other worship displays belong to the Hindu, Lutheran, Doukhobor, Muslim, Eastern Orthodox, Judaic, and Roman Catholic traditions. Several are superb collections, especially the Judaic material from the old Vegreville synagogue before it disbanded, and the Douhkobor objects, which must represent the best in Canada. It is remarkable that this tasteful and rich exhibit is housed in an area not much larger than seven metres by twenty-five metres. Little wonder that the gallery has been somewhat of a pilgrimage site for many of the groups represented here.

8 Unfortunately that brings sharply into view one glaring problem of the exhibition: it is extremely limited, both in terms of the religions covered, and its interpretation of religion. The single metaphor is tradition. It dominates the horizon of the curator's conception of religion. What of those spiritual enterprises that have little "tradition"? If Alberta is known for its conservative Christian perspective, perhaps even its fundamentalism, where has that appeared in this gallery? That may be a stereotype, but it would seem necessary to address it in some manner. Moreover, what of the rich and variegated traditions of the native people? While a photograph of a sacred circle is added, almost as an afterthought on the wall as one leaves the gallery, it seems a diminuation of religion in Alberta not to have included something of those rich cultures. Hence the exhibit, as ground-breaking and extraordinary as it may be, fails to encompass either the multifaceted nature of religion or Alberta's own spiritual legacy. What we have is a very suggestive expression of a work that has only just begun.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 59 For all that, the most powerful message it may give is to those groups who found it difficult becoming part of Canada. The Doukhobors, so used to being maligned and misunderstood, are justified in weeping before a sensitive and appreciative treatment of their faith. And Jews and Muslims, so bombarded with antagonisms against each other from abroad, can join in accepting the sacredness of each other in a setting that accepts the genius of their individual traditions without favour. As a symbol of legitimation, "Spiritual Life — Sacred Ritual" may then be one of the most significant that has been mounted in our country. And it may indicate the importance of spiritual life in our culture in a way that has hitherto received little public appreciation.

Curatorial Statement

10 The Folk Life Program of the Provincial Museum of Alberta came into being several years prior to the opening of the Spiritual Life — Sacred Ritual Gallery. Its mandate was to research, document, and collect material on the cultural life of Alberta's many communities with European, Oriental and Latin American roots. Tight on the heels of the establishment of the new program, the opportunity to develop a permanent gallery was a great challenge. So many exhibitions that have attempted to deal with the cultural diversity of Canada have selected sample artifact material from each tradition, labelled it, then bracketed the entire exhibition between a comment on immigration and settlement patterns, and a few visuals of contemporary song and dance routines in ethnic costume. This is an appalling diminution of the structure and meaning of the very fabric of human life. Milan Kundera's discussion of the colonization of cultural memory in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (New York: Penguin Books, 1981) seems an appropriate comment on the implicit way Canadian museums have treated the cultural patrimony and the living tradition of every Canadian, with the exception, perhaps, of the two dominant cultures (French and English) and that of the native people. The reasons for this are beyond our current discussion. It was, however, the desire to speak about a significant aspect of the cultural patrimony and living tradition of Alberta's numerous peoples that led me to consider themes in human culture which could be addressed in this gallery.

11 The terms of reference for the exhibition called for it to include reference to a number of the cultures that exist in Alberta. Because the Folk Life Program had come into existence two years earlier, we had virtually no collection from which to draw. As a result, it was necessary to choose a theme in human culture that had a material culture component, examples of which exist in the province; could reflect the cultural diversity in Alberta; showed an aspect of culture shared by a number of national cultures, so that more than one ethnic group would be reflected in each vignette; had an institutional network to smooth the field-work and collections tasks, which had to be done quickly; and, finally, was an aspect of culture of importance to the patrimony of the community, and a part of the living tradition.

12 The ritual life of human culture was a natural choice, given the cultural and institutional landscape of Alberta. Numerous peoples have come to the province because of religious persecution. Church, Synagogue, Mosque, and Temple remain the primary cultural institutions for many in the community. That the religious aspect of human culture had been studied a good deal was also important. Ritual studies, however, are rare. In North America, virtually nothing has been done on ritual life and popular religious practice. Hence, this choice provided an area for substantial research and a potential contribution to scholarship. The study of religion is my primary area of scholarship, so this was of importance, as well.

13 The research phase of the gallery was singularly fruitful for the development of the Folk Life Program. We had remarkable success in field-work in the communities. The religious leaders across the province gave us complete access to the ritual cycles, and families cooperated graciously. We established a significant collection of documents, ethnographic and historical photographs on ritual life, and a marvellous artifact collection. The museum's reputation as the domain of the peoples of Alberta was established in communities, many of which are not its natural constituency. This had a salutary effect on the overall Museum Program and has led to the development of a well-balanced artifact collection, representative of the cultural life of the communities in general.

14 The structure of the exhibition allowed us to use material from several ethnic communities in each vignette. For example, Russian, Ukrainian, Greek, and Arab items are in the setting for the Divine Liturgy of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The themes of worship and rites of initiation run like a thread through human culture. Consequently, the exhibition has a coherence that makes it possible to address the profound ideas and images at the heart of human culture.

15 The gallery has functioned in a variety of ways. When visitors enter the gallery, they commonly seek out something familiar. They stop in front of Lutheran Worship, for example, to look, read, and think, then they turn to several other traditions considered in the gallery. They spend a considerable amount of time in this process of examination, of seek and find. The Moslems, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Christians represented in the gallery use the exhibits somewhat more specifically. They commonly bring Sunday School groups to the gallery, and use it in their educational programming. Many of them have requested lectures in the gallery for adult education groups, as well. For some of the newer immigrant communities, such as the Hindus, Sikhs, and some of the Moslems, the gallery has become a kind of pilgrimage site. They bring dignitaries to the exhibition and show them that in Alberta, the province with the redneck reputation, they, too, are a legitimate part of the cultural world. Their view of the meaning of life, their practice of what is central to the human imagination, to human culture, it valued. And indeed it is.

16 A final critical note. The gallery does not meet my expectations at the interpretive level. There is grave danger that ethnographic exhibitions portray an aspect of culture as if it were fundamentally foreign, strange, or esoteric. Pedagogically, I would like to see the Spiritual Life — Sacred Ritual Gallery designed to balance the reverence it now exudes, with images drawn from secular society that show how men, women, and children continue to address the sacred, whether in wonder, adoration, regard, or through simple quest. The use of these images to initiate the public to the gallery would help to bridge the concern for the sacred in all human culture, including the secular, with the specific way that concern is expressed in the classical religious tradition discussed in the gallery.