Research Notes / Notes de recherche

In Mourning

1 The practice of mourning symbolizes one of the most dramatic and major differences between this century and the last and is an integral aspect for the study of nineteenth-century women and children. From the hundreds of items that have been bequeathed and entrusted to Canadian museums, we know the customs were widespread, but little has been written on the purely Canadian features.

2 The New Brunswick Museum is especially rich in artifacts connected to mourning practices. Although these have been documented, the isolation of mourning artifacts is only a beginning. More research and study is necessary to determine the psychological effects on women who were obliged to wear unbecoming and even ugly clothes for what must have been literally years of their lives.

3 Was there a difference in the attitudes of young girls and boys to the prospect of dying? After all, boys did not have to work mourning samplers or labour over needlework verses that welcomed death. In addition, women alone faced the ultimate risk almost yearly during childbirth. Was this a factor in the seemingly calm acceptance of their fate as illustrated in this inscription taken from a tombstone at Gagetown, New Brunswick,

Aged 25 years 3 mos & 28 days

Death, pale death arrived without control

Called me away in haste before t'was noon

My Sav'our Jesus thot it not too soon.

Of Gershom Clark, I was the lawful wife

In childbed was forced to resign my life

My still[?] born infant on my feet it lies

In the cold grave till we are called to rise.

The following text presents aspects of mourning behaviour that would have been expected of New Brunswick women in the nineteenth century, as well as a sampling of the artifacts that were the outward signs of that behaviour.1

4 The realities of death in the nineteenth century were a constant and accepted aspect of everyday life. Rather than attempt to hide it away or shield themselves from the harsh facts, the Victorians especially confronted it, eulogized it, and finally, reduced it through mourning to a test of class.

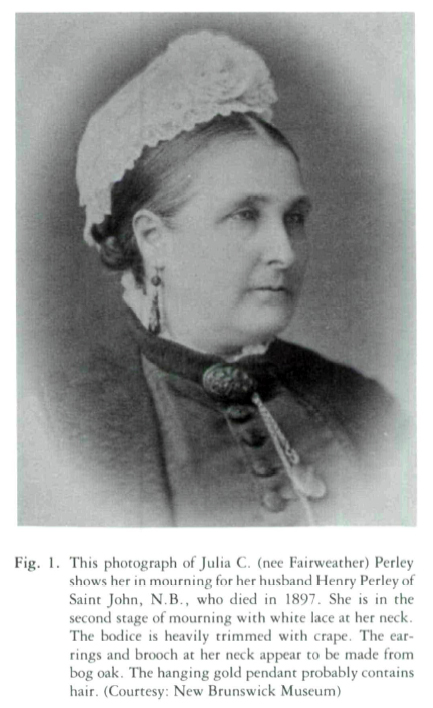

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 The rules for mourning conduct and dress were complicated, sometimes conflicting but always obligatory and expensive. It reached its zenith from the 1850s to the 1880s and affected not only the upper and middle classes but the poor as well. Ostentatious and public displays were necessary rites following death. Mothers who were facing financial disaster still had to expend money on mourning because non-compliance was regarded as a sign of disrespect and the result could be social ostracism. In a class-conscious society always searching for an upward move, this was catastrophic. Unlike today, grief was not considered a personal or private matter, nor was it meant to be quickly put away; rather it was intended as a long-lasting public spectacle.

6 These assertions are well supported in the book Canada Home: Juliana Horatia Ewing's Fredericton Letters, 1867-1869.2 In a letter to her mother dated 2 October 1868, Juliana, the wife of a British military officer stationed in Fredericton, describes going to the home of a family who had just lost their first-born child. She had never met this family before but went with a friend and obviously felt little compunction about intruding or sharing the funeral dinner.

7 Some of the differences in dealing with death between the nineteenth and late twentieth centuries are self-evident in this account. Juliana's off-hand approach could be construed as mocking and almost unsympathetic. Her constant referral to the child as "it" sounds callous to modern ears, but in a time when almost one third of all children died, an arms-length treatment was perhaps the only way to live with reality. Women, who at this time, were generally relegated to the background of any important event, assumed a major role in overseeing the maintenance of proper etiquette and behaviour and honouring traditions and rituals. Hardly surprising, as all through the nineteenth century women were used to portray the family's respectability, Christian piety, social standing and wealth. Mourning and its accoutrements were the ultimate showpieces for these attributes.

8 For the death of a child or an older unmarried girl, the trappings at the funeral were white, but black was the primary colour of mourning. After the funeral, men needed only to wear a black armband to denote their loss. The width varied according to their relationship with the deceased — four inches wide was standard for a wife. However, the burden of mourning was borne more heavily by women, especially widows. They had to go into deep mourning for a year and a day. This required being clothed, outwardly at least, from head to toe in dull black with the addition of crape as a trimming. The manufacture of crape, a transparent crimped silk gauze, was a major industry when mourning rites and rituals were at their height of popularity. It was used extensively as a trimming in the house and on clothing. It was sewn lavishly on the bodice and skirts of dresses and in addition, bonnets were made from it and the long face veils were edged with it.

9 Although changing abruptly from deep mourning into part mourning on the day specified was frowned upon, the widow could gradually change from dull black to black silk or satin. Of course, it still had to be trimmed with the ubiquitous crape which could not be discarded until at least eighteen months after the death of her husband. It would be two long years before the addition of a shade other than black was permitted. When half-mourning commenced, white, grey or lilac could be included.

10 Mourning clothes were not just applicable upon the death of a husband. It was also mandatory for women to wear black and observe mourning for eighteen months after the death of a parent; six months for a brother, sister or grandparent; and if she was married, mourning had to be observed in exactly the same manner for her husband's relatives as for her own.

11 The death of a child, so tragically common, meant mourning clothes for twelve months. Nor were more distant relatives ignored; six weeks to three months mourning was customary for a first cousin or an aunt or uncle. Widowers were free to remarry as soon as they wished. However, if it was within two years, the new wife was expected to wear only black or shades of half-mourning in memory of her predecessor.

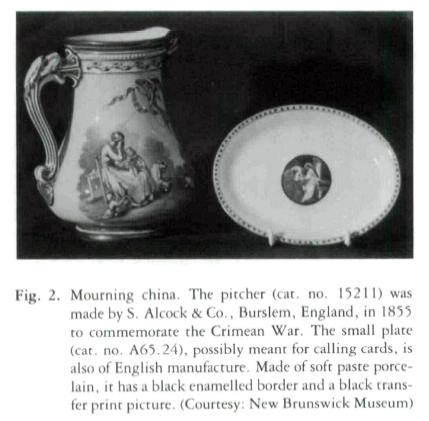

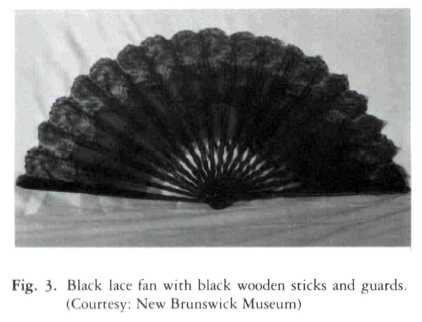

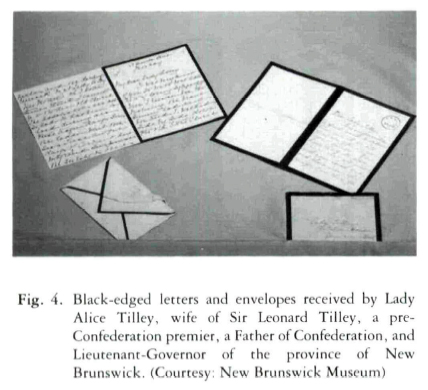

12 Accessories, such as fans, gloves, handbags, and parasols, were also made in black. In some cases, women went so far as to have their underwear edged with black. But the colour restriction went beyond clothing and accessories. Calling cards, another aspect of the polite society, were edged in black, as were writing paper and envelopes. In some instances, families went so far as to have mourning china.

13 The ban on glitter or shininess extended even to jewellery. Bog oak, with its dull black finish, was carved and shaped into brooches, earrings, pins and necklaces. Jet, originally a type of black slate, was extremely popular for the same purposes. Later, jet was copied in black glass.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 414 Memorial wreaths and jewellery made from hair, often of the deceased, were ideal for the Victorian perception of, or obsession with, death. Often hair jewellery was set into gold, as this could be worn.

15 Preceding a long and complicated set of directions for weaving or plaiting hair, this foreword appears in an 1855 fancy needlework instruction book:

It must also have been one of the most frustrating, laborious and time-consuming crafts devised by anyone. Yet, the popularity of hairwork is shown by the many examples existing in museums today. Although some pieces were made by professionals, most were made by a female member of the family as a labour of love. Pictures of the deceased were often done when they were in their coffin. Hair wreaths and wax flowers were popularly used to surround these memorial pictures or an existing one, which would then hang in a place of honour on the parlour wall. If there was a portrait of the deceased already hanging, it was usually draped in crape.

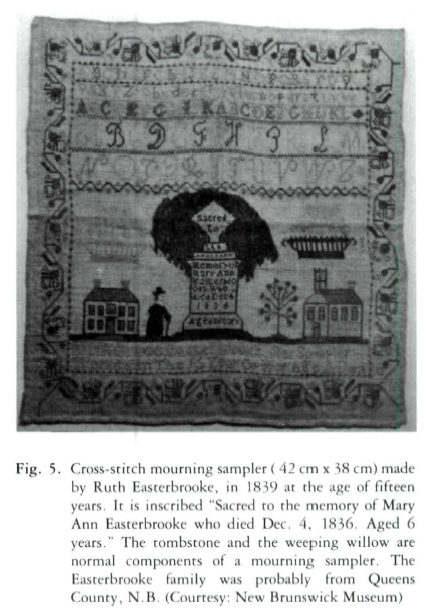

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 516 Far from being shielded from the horrors of the grave, children were encouraged to accept their own and others mortality. A cross-stitch sampler made by a twelve-year-old girl in 1851, has this morbid message:

How clay cold now these once warm lips

Which mine so oft have prest

And silent is that prattling tongue

In everlasting rest

17 Mourning or memorial samplers with designs that usually included either a tombstone or a weeping willow were commonly made by schoolgirls with needleworking abilities that are the envy of adult women today. During the latter part of the last century, "In Memoriam" cards were mass produced and provided by the undertaking establishments.

18 The study of the lives of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century New Brunswick women and children is on-going at the New Brunswick Museum. Understanding the complex subtleties of their attitudes to death and mourning will inevitably lead to greater understanding of their total lifestyles.