Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Carved in Stone:

Material Evidence in the Graveyards of Kings County, Nova Scotia

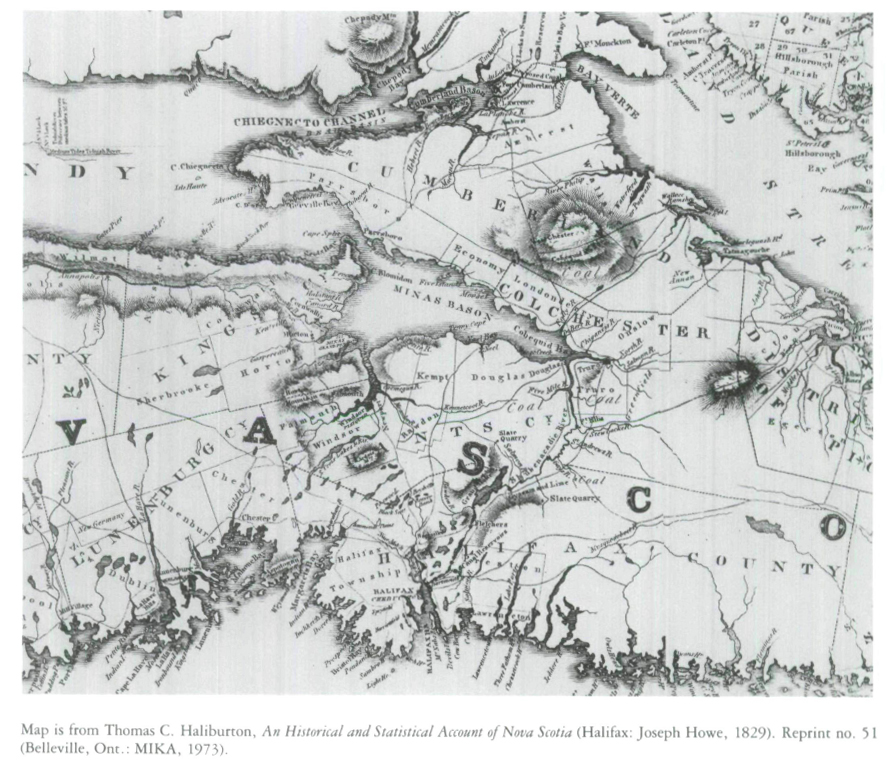

1 Although gravestones reveal much information to the trained eye, they have received little recognition as artifacts of Canada's past.1 In addition to presenting genealogical information and quaint epitaphs, gravestones reveal clues to the cultural background of and influences on both the decedents and the craftsmen who fashioned their stones. As well, these artifacts hold particular significance to the study of material culture in that those surviving are in their original settings and continue to function as intended. In Nova Scotia most of what is known about life in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries has been gleaned from documents — diaries, newspapers, correspondence, wills, deeds — and the story they tell is far from complete. To understand more of this period, we have begun to investigate Nova Scotia gravestones, combining artifact information with historical records, thereby relating material, maker and location of the stones with what is known about the people they memorialize and the communities in which those people lived. This report discusses the findings of research to date.

2 A cursory examination of the old graveyards of Nova Scotia reveals that gravestones pre-dating 1780 are generally made of slate, ornately carved in the style common around Massachusetts Bay, and in fact, imported from there.2 Between 1780 and 1840 most stones were made locally by Nova Scotian craftsmen and can be grouped by area, according to common characteristics of material and style. For the most part, Halifax stones were carved in sandstone in very high relief by Scottish stonemasons who originally came to the capital to construct public buildings. A few stones of this style can also be found in the nearest major towns to Halifax — Windsor and Lunenburg — where they stand alongside more primitive local carving of the same period. From Liverpool to Yarmouth there are imported New England slates (more common and of later date), a few Halifax sandstones, and an obvious "south shore" style of crude carving on local scaly schist.3 Throughout Cape Breton, as well as Pictou and Antigonish counties, eighteenth- and very early nineteenth-century stones are uncommon, but those that survive are usually sandstone and of formal design. In Cumberland and Colchester counties there are also few early gravestones, and their style is more folksy. Around the Annapolis River, the old stones tend to be sandstone carved in a style popular along the Saint John River, just across the Bay of Fundy. In Kings County, Nova Scotia, another distinctly identifiable carving style can be found. There are more than a hundred stones in this style, a remarkable number compared with other rural areas. This concentration is due perhaps not so much to survival as to the fact that this was one of the first English-speaking areas of the province to develop a local economy capable of supporting a resident gravestone carver.

3 Our research to date has focussed on the area of Kings County that was set off in the 1750s as the townships of Horton and Cornwallis. These townships were settled in the early 1760s as part of a campaign by the Nova Scotia government to attract New Englanders to the colony. Just a few years before, and after almost one hundred and fifty years of habitation, the colony's resident French Acadian population had been forcibly deported and the land lay empty. Between 1760 and 1764 more than five thousand New Englanders took up grants of free land ranging from 250 to 1000 acres in eleven townships of approximately 100,000 acres each, located along Nova Scotia's southwestern shore, the Annapolis Valley, the Minas Basin and the Chignecto Isthmus.

4 Prospective immigrants from the land-hungry agricultural areas of New England were especially interested in the fertile alluvial farmland in the heart of Acadia at Les Mines (Minas). The Nova Scotia government partitioned this land as the townships of Cornwallis, Horton and Falmouth. These townships were to be colonized as block settlements, i.e., each was granted to a group of families and individuals who were expected to move from New England to Nova Scotia as a community, and to occupy the land, at least initially, in common. But as the colonization proceeded, forfeitures, vacancies and the influx of non-grantees led to the settlements of the Minas townships by a diverse group of proprietors. In Horton, for example, three components can be recognized in the final selection of grantees: 177 New Englanders, 14 soldiers and 11 placemen.4 Still, most of the grantees, perhaps 88 per cent, were New Englanders. Male grantees ranged in age between 15 and 66, more than two-thirds were married and brought between one and ten, but most often four, children under age 21 to the new land. Many families included one or two sons aged 16 to 21 who were not grantees and could labour on family farms.

5 Little of the economic backgrounds of the New England settlers can be known without reconstructing their lives before emigration. While it is very unlikely that the extremely rich or the very poor came to Kings County, the sparse evidence suggests that the grantees represented a broad economic spectrum. For instance, such men as prominent Connecticut landowner Robert Denison, Yale-educated lawyer Nathan Dewolf, and Col. Charles Dickson (who personally financed a military company for the siege of Beausejour) came to Horton, but other settlers could not survive the first few years without food and grain subsidies from the Nova Scotia government. Although almost every man called himself a yeoman farmer when he claimed a Horton share, the New Englanders brought a variety of skills to the new land. A small number identified themselves as blacksmiths, carpenters, cordwainers, weavers and traders, while others relied on informal training to build their houses and provide their families with the basic possessions they had not brought with them.

6 If the origins of the 79 New Englanders who settled in Horton for whom we have data are typical, members of this largest group of grantees came from a compact area of southeastern Connecticut focussing on the port of New London and including the towns of Lebanon, Colchester, Norwich, East Haddam, Lyme and Stonington. A few others came from communities along the Connecticut River.

7 The gravestones that still stand in Horton as memorials to these New Englanders are different from those found in their hearth areas. In southeastern Connecticut, mid-eighteenth century gravestones are mainly granite, with shallow carved angel-head motifs (soul effigies), predominantly the work of Benjamin Collins, the Manning family and their imitators.5 This style of carving contrasts sharply with the ornate and deeply incised sandstones of the Connecticut River Valley. Both major Connecticut carving styles differ considerably from the slate carving styles of Massachusetts and Rhode Island.6 In fact, the gravestones of Kings County bear little resemblance to those found anywhere in New England from the mid-eighteenth century.7

8 The oldest Kings County gravestones date from about 1770 to 1820. The earliest are probably "backdated" — carved some time later than the dare indicated on the stone. From the evidence of the stones, there does not appear to have been anyone carving gravestones in Horton before the 1780s. The oldest markers appear to be primarily the creation of two stonecarvers, working exclusively in sandstone. The first is referred to as the "Second Horton Carver" because his name is unknown and he succeeded an earlier carver who worked only briefly in the area.8 The second has been identified as Abraham Seaman. These attributions have been made following a systematic investigation of the older burial grounds in Nova Scotia. Pre-1830 stones were closely scrutinized and grouped in terms of material, shape, lettering, image, border, word groupings, and any other visibly identifiable characteristics. Probate records were then studied for any reference to individuals being paid to carve gravestones. This kind of information is rarely noted in estate settlement papers. Not every death involved an estate settlement (especially those of young men, children and many women), and not all probate records have survived. Thus the identity of the Second Horton Carver remains a mystery.

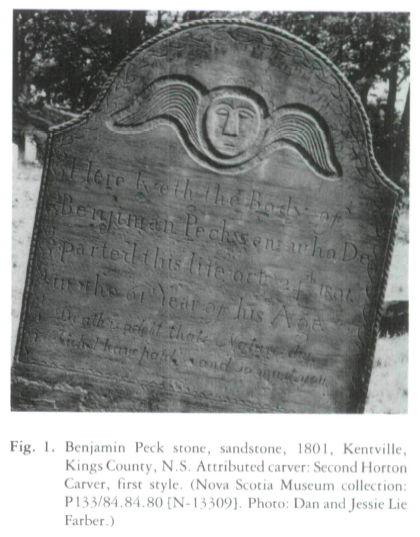

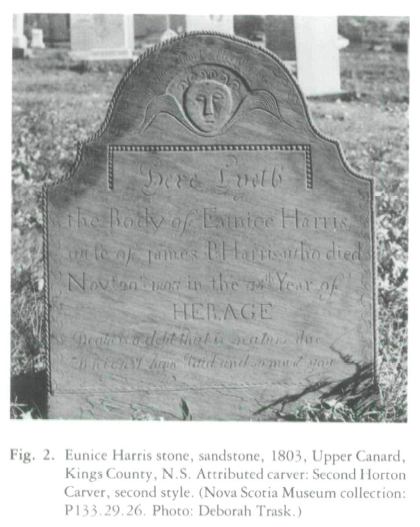

9 Stones attributed to the Second Horton Carver date from 1798 to 1805 (Appendix A).9 He carved crude, sad faces with an elaborate carved "rope" edge and vining or "bird-track" border. His earliest stones have deep outlines around the winged-head image, or no image at all and a plain curved shape at the top edge (fig. 1). Later the top edge shape became more elaborate and he added a plain or beaded bracket around the "Here Lyeth" part of the inscription (fig. 2). There is also a further cutting away above the head, and often the epitaph "Death is a debt that is nature's due/Which I have paid and so must you" He never mastered the depiction of hair. A curious distinguishing mark of the Second Horton Carver is a tail on the cross bar of the "f" in "Here lyeth the body of." Stones with these characteristics are found in all the old burial grounds of Cornwallis and Horton, with some at nearby Falmouth and Windsor. A few stones for former residents of Horton have been discovered outside the area. There is one for Charles Dickson at St. Paul's Cemetery in Halifax, and another for Susannah, wife of Nathan Harris, at Liverpool.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

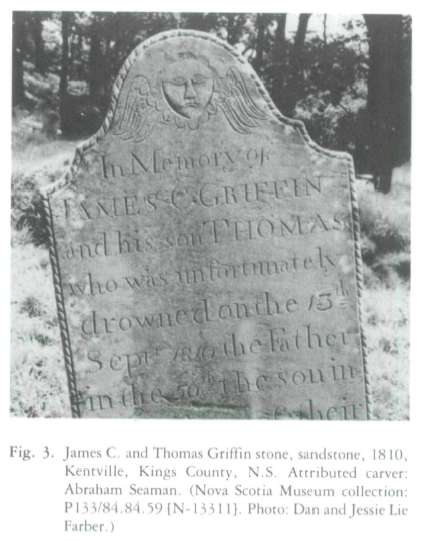

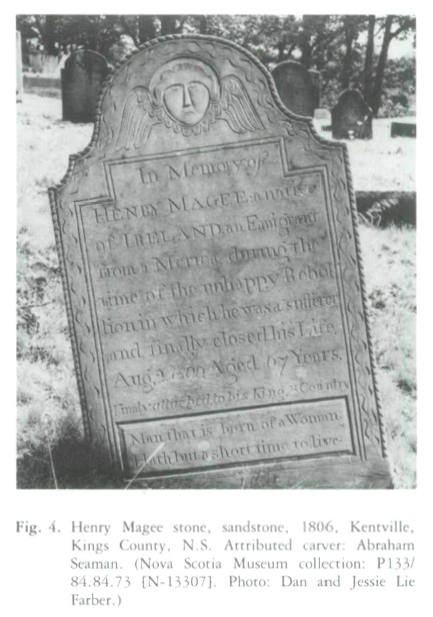

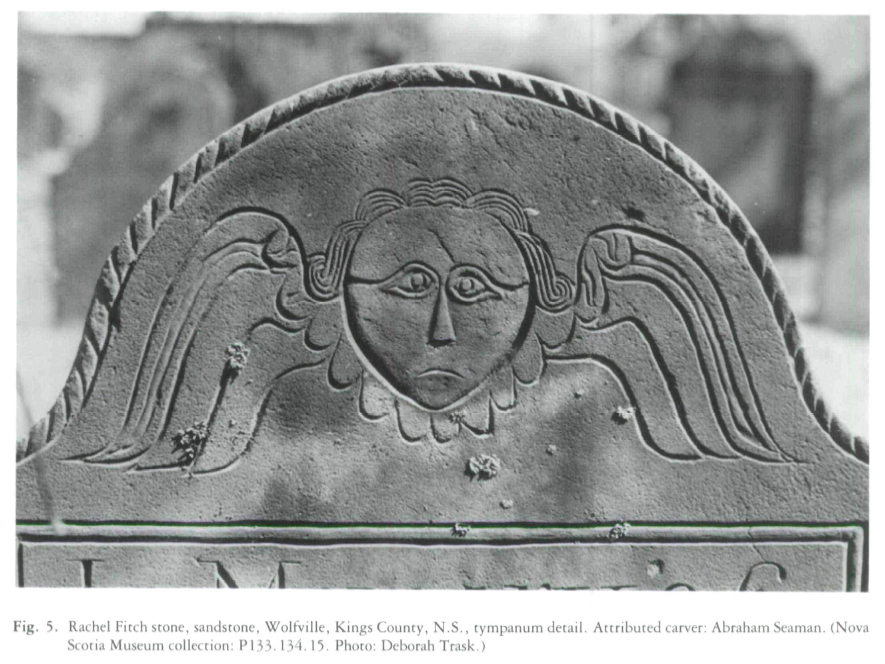

Display large image of Figure 210 Field investigation has revealed a second style of carving in stones dated from 1805 to 1821 (Appendix B).10 This carver also used the elaborate carved "rope" edge, the vining or "bird-track" border, and added a swirl to the cross bar on the "f " in "In Memory of," but he executed these decorations with greater dexterity (figs. 3 and 4). He generally carved the name of the deceased in capital letters. His technique is undoubtedly derived from the earlier style, as there is a clear visible link between the two. He may have learned the trade of stone carving from the Second Horton Carver. It is quire possible that this carver and the Second Horton Carver are the same person, and these stylistic variations show the evolution of carving skill in one craftsman.11

11 Documentary evidence identifies this carving as the work of Abraham Seaman. Probate estate papers for three decedents whose stones have these characteristics record a payment to Abraham Seaman for gravestones.12 Seaman is also mentioned in the journal of Edward Manning, minister of the First Baptist Church in Cornwallis. On April 30, 1818, six weeks after his daughter Eunice died, Manning recorded: "Saw Mr. Abraham Seamans, presented bill for Eunice's gravestone, 6 pounds, 4 shillings, but he deducted 1 pound 4 shillings."13

12 Abraham Seaman was the son of Jacomiah Seaman of Westchester, New York.14 During the American Revolution, Jacomiah's four sons joined Col. Lowther Pennington's Regiment of Kings Guards, and so became members of the group known as the Westchester Loyalists.15 After the war many Westchester Loyalists received land grants in Cumberland County, Nova Scotia. Jacomiah and his son Stephen each received a 500-acre grant at "Cobequid Road," Cumberland County, and later were granted a second tract near River Philip.16 Jacomiah probably settled in the township of Fanningsborough (now North Wallace).17 In 1788 his son Abraham "of the township of Westchester, County of Cumberland, yeoman" bought 50 acres on the north side of the main road leading from Amherst to Cobequid (Truro), which he sold less than two years later.18 In October 1794, at the age of twenty-four, Abraham Seaman of Westmoreland, Cumberland County, bought a house and a one-acre lot in Horton.19 The following year he married into a prominent Horton family and lived there until 1821, when he moved back to Cumberland County.20

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 413 In the intervening years, Abraham Seaman had amassed considerable land holdings in Cumberland County. In 1802, Abraham Seaman "of Horton, Kings County, merchant," bought some land at River Philip. In September of 1806 he bought an additional 1000 acres at River Philip, and the next month, listed now as a mason, he bought some more land in Horton. Years later, while helping his brother Stephen settle a land dispute at River Philip (now Pugwash), he swore that "...in 1806 I went from Horton to Pugwash Built a House on the West side of Pugwash harbour the first there ever..." But, as far as we know, he continued to live at Horton. In March 1811 he bought dyke land at Horton; in October of the same year he bought five tracts of land including a hall interest in a sawmill at River Philip from his brother Hezekiah. On all of these deeds he is listed as being "of Horton."22

14 As a landowner, merchant and mason, Seaman was probably involved in a variety of business activities during the time he lived in Horton. One of his most enduring was making distinctive gravestones for his neighbours. In part, Seaman's stones have survived because of the material he used. His stones are a high-quality, dense brown sandstone that seems out of place in a settlement bordering the Bay of Fundy. It bears little resemblance to the material used by his son, Thomas Lewis Seaman, when he made gravestones in Kings County during the 1830s and 40s.23 The younger Seaman relied on a more porous, reddish sandstone which seems to be characteristic of the Minas Basin area. This stone has succumbed over time to water damage, and has become very crumbly. The superior material used by Abraham Seaman is more like the stone found at Remsheg (Wallace), Cumberland County. Stone from the Remsheg quarry was used to build Province House in Halifax, which was finished before 1819. The architect, Richard Scott, bought the land on the Remsheg River that included the stone quarries in 1814.24 The deed implies that the quarries had been worked previously, but precisely when sandstone was first quarried there is unknown. If sandstone was being transported from Remsheg to Halifax, could it also have gone to the Horton-Cornwallis district? We know that the house built for Charles Ramage Prescott in Cornwallis Township, completed before 1817, has a sandstone foundation and lintels. Although the brick for the house was made nearby,25 the source for the sandstone has not been ascertained. We do not know if Seaman had access to Wallace sandstone. Until the early Kings County grave-scones are analyzed by a geologist, conclusions about the source of Seaman's sandstone are tenuous at best.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 615 Still, if Seaman transported his raw material from north Cumberland County, this would reveal patterns of trade and perceptions of distance and travel in turn-of-the-nineteenth-century Nova Scotia. Undoubtedly Seaman himself travelled this route regularly to maintain his family and business connections in Cumberland County.

16 In addition to material, maker, and origins of the people for whom the markers were made, the gravestones were examined in the context of the lives these people lived in Horton. An analysis of the stones according to origin, religion and place of residence of the decedents, their economic standing within the group of founding settlers, and kinship ties to each other and to Abraham Seaman reveals that the only connection most share is the timing of their arrival in Horton. Almost all extant stones for the period 1770 to 1820 for this area of Kings County commemorate the township's grantees. Few exist for those who took up residence after all the land in the township had been granted, even though this group represented a significant component of the population. Between 1770 and 1791 at least 177 men and their families became residents of Horton.26

17 In that time, restricted access to land resulting from land granting policies, the accumulative impulses of a handful of the largest landowners, rising prices and increased pressure of population lessened everyman's opportunity to own a farm. As a result, few latecomers ever acquired land. For the most part they rented property or laboured on someone else's farm. There were few alternatives in this subsistence farming community. Almost immediately, society stratified on the basis of land ownership. Thus when Hortonians were finally laid to rest, it was those who had taken part in the initial settling and had obtained free land grants who were in a position to have gravestones erected in their memory.

18 The carver of these gravestones was a native of Westchester, New York, and not a native of New England, and thus his cultural traditions may have been different from those of the people whose memorials he carved. He did not settle immediately in Kings County when he came to Nova Scotia, and the fact that he may have transported the material for his work from the area where he first lived (and continued to own property) raises some questions about why he moved to Horton. In eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century New England, carvers usually lived near the stone quarry.27 When Abraham Seaman began carving in Horton, it was the shire town of the most populated county in the colony (except Halifax) and the first generation of settlers was dying. Had he located close to his market?28

19 Like the Cape Cod cottages and Georgian houses that dot the countryside, the old gravestones of Kings County seem to be part of the New England cultural traditions that are stamped on the landscape. As we begin to examine these artifacts more closely, it is clear that the story they tell is more complex than it purports to be. Memorials in one area of Nova Scotia for pre-Loyalist settlers from southeastern Connecticut were carved here by a Loyalist stone carver from New York, but bear little resemblance to markers in those areas. Although more research has to be done in this regard, these gravestones were apparently carved by Abraham Seaman in a style distinctive to Nova Scotia.