Articles

Beautifying the Boneyard:

The Changing Image of the Cemetery in Nineteenth-Century Ontario

Abstract

Scant attention has been paid by Canadian historians to the historical study of death. One neglected area is scholarly study of cemeteries — arguably the most durable artifacts of death and death-custom.

British and American research suggests that the Victorian creation of large, non-sectarian community cemeteries resulted from health considerations and was entirely an urban phenomenon. Monuments like Boston's Mount Auburn were substantial cultural institutions and tell us much about Victorian society. These so-called "rural cemeteries" were built beyond city limits and evolved in large centres into architecturally designed "garden" or "park" cemeteries, as well illustrated by Toronto's Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

Surviving records of small-town cemeteries, such as in Norwich. Ontario, show the development of non-sectarian, although often still Protestant, cemeteries which, by upkeep and location, remained an integral part of the community. In urban centres, the beautification movement challenged the sectarian aspect of burial and represented a degree of secularization. These new cemeteries featured the concept of perpetual care and built picturesque chapels so that the entire process of burial could be catered in the setting of a romantic rural sepulchre. Diurnal interaction with death's symbols was thereby ended, with the result that the cemetery park movement contributed to "the dying of death" by the First World War.

Résumé

Les historiens canadiens n'ont guère effectué jusqu'ici d'études historiques sur la mort. Les cimetières, notamment, qui sont sans doute les manifestations tangibles les plus durables de la mort et des coutumes liées à la mort, ont ainsi été négligés.

Des recherches américaines et britanniques donnent à entendre que la création, à l'époque victorienne, de grands cimetières non confessionnels naquit de considérations sanitaires et fut un phénomène exclusivement urbain. Des monuments comme le cimetière Mount Auburn, à Boston, étaient d'importantes institutions culturelles et nous apprennent beaucoup sur la société victorienne. Ces «cimetières ruraux». qui étaient construits à l'extérieur des villes, devinrent dans les grands centres des «jardins» ou des «parcs» paysagers, comme en témoigne le cimetière Mount Pleasant de Toronto.

Nous savons, d'après les archives qui nous sont parvenues, que dans des petites villes, comme Norwich, en Ontario, sont nés des cimetières non confessionnels, mais souvent encore protestants, qui, grâce à leur entretien et à leur emplacement, conservent une place importante dans ces localités. Dans les centres urbains, la tendance à faire de «beaux» cimetières a éliminé en grande partie les barrières confessionnelles et a constitué un pas vers une certaine sécularisation. Dans ces nouveaux cimetières, constamment entretenus et dotés de jolies chapelles, l'enterre-ment avait lien dans un cadre romantique à caractère «rural». Les symboles de la mort ayant disparu. le «cimetière-parc» contribua ainsi, à l'époque de la Première Guerre mondiale, à «la mort de la mort».

1 Scant attention has been paid by Canadian historians to the historical study of death. Although British, American and especially French scholars have explored the topic in multidisciplinary detail, Canadian interest has largely been either genealogical or antiquarian.

2 The study of death in the past offers considerable opportunities for the cultural and social historian of Canada.1 One obvious and almost entirely neglected area is scholarly study of cemeteries — arguably the most durable artifacts of death and death-custom. What follows are some preliminary ideas relating to discernible trends in the establishment of Ontario burying-grounds in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It is hoped that this discussion will convey something of the broad scope of this uncharted topic, reveal the difficulties in conducting research, and suggest some of the benefits which perseverance can produce.

3 As with so many other aspects of Canadian life, cemetery planning and establishment have been largely derivative. The historical literature suggests that in England and the United States early Victorian trends toward the establishment of large, non-sectarian cemeteries were almost exclusively urban impulses; the bourgeoning population created a variety of pressures which could not be met by sectarian burying-grounds within city limits. A further, equally bourgeois, consideration was the matter of health: British and American journals of the period are filled with references to the dangers of disease-ridden and crowded "boneyards," where visible rot, vandalism, stray dogs and insufficient coverage of remains combined to create severe health hazards. To these very practical matters might be added the less tangible but intense psychological and emotional preoccupation with death and mourning that developed in the Victorian age. Romanticism, combined with an appreciation of the naturalness of death and a renewed spiritual emphasis upon its implications, created new attitudes towards the subject. Burial-grounds were no longer cast-off, melancholy boneyards, but were dignified with names from the classical lexicon like necropolis or cemetery. They were to be planned places of beauty where the dead and the living might mingle in restful reflection.

4 The classic prototype of such a cemetery in the United States was Boston's Mount Auburn, opened first in 1831. Good British examples were the Glasgow Necropolis, London's Kensal Green or the better-known Highgate Cemetery. All reflected a change in attitude towards death, but they also conveyed certain other attributes. From the beginning they were celebrated for their beauty, both contrived and natural. They were, in today's parlance, "showcases" for the aesthetic arts of the time. They pre-dated the enthusiasm for massive public parks and may have had something to do with generating that enthusiasm. They reinforced, indeed celebrated, the bourgeois fabric of nineteenth-century life, providing an opportunity for discreet pride and restrained boastfulness in achievement to be paraded by successful Victorians. In North America they were strong declarations of coming of age and sophistication, and confidently declared to Europe's older civilization that civilization was well and truly entrenched in the New World too. They were, in short, substantial cultural institutions and much can be learned of Victorian society through their study.2

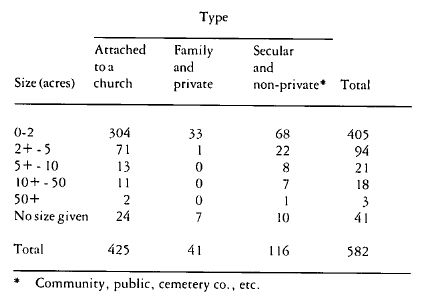

5 The name accorded to these new types of burial-grounds was "rural" cemetery. The adjective is misleading for they were rural only in the sense that they tended to be somewhat larger than the typical churchyard and were placed on the outskirts of the community; they certainly did not reflect the contemporary state of most country burying-grounds. Early Ontario models of what might more appropriately be termed "garden" cemeteries were Kingston's Cataraqui Cemetery and Toronto's Necropolis, and late nineteenth-century examples abound in such Ontario towns and smaller cities as Durham, Paris, Brantford, and Belleville.

6 By the time garden cemeteries became common in southern Ontario the cemetery movement in the United States had evolved further towards a philosophy of cemetery design which might most appropriately be called a "park" cemetery. The new "cemetery beautiful" exponents wished to curtail the use of iron-railed plots (such as the joint Strachan-Robinson site at Toronto's St. James) and the tall headstones which so characterized the garden cemetery. Preferring name plates embedded flat into the ground, these planners designed sweeping park-like vistas. A somewhat unconvinced public, not to mention monument manufacturers, resisted the demise of upstanding monuments and therefore the complete realization of a "natural" scene, but the general design features sought by these landscape architects are well laid out in parts of Toronto's Mount Pleasant Cemetery. The entire park movement was, in fact, wrapped up with the growth of professionalism in cemetery superintendence and wedded as well to the nineteenth-century paradigms of efficiency and progress. Strong links with the "city beautiful" movement in the period 1880-1920 might be suggested.3

7 New Canadian cemeteries were behind, but not far behind, British and American rural cemetery models. Canadians faced similar problems. The cities of mid-nineteenth-century Ontario, for example, might not have rivalled the number and sizes of their American or British counterparts, but places like Toronto, Kingston and London also faced difficulties of overcrowding, commercial clamour for land, and public concern over the health hazard. Canadians, as well, read British and American literature on the subject; in addition, because the garden and park cemeteries were considered showpieces, many Canadians had visited celebrated American and British cemeteries when travelling abroad.4

8 In fact, changing modes and attitudes toward burial in Ontario can be considered as a reflection of the province's degree of urbanization. In the cemeteries of Ontario one sees an evolution from the predominance of religious and "communal" cemeteries, towards the ascendency of the cemetery beautiful as an ideal. Originally the burying-ground was organically part of the social and geographic landscape in early Ontario communities, rural and urban. From the growing cities, however, emerged the beautification movement, which at core and from both private and public inspiration, encouraged the formation of nondenominational, well-planned and strictly kept-up cemeteries. Disgust or dismay was often expressed over the state of existing country burying-grounds by those who expounded the establishment of more of the "beautyspots that mark our non-sectarian cities of the dead...." Although the creation of a cemetery park, to which mid-Victorians often would walk for a Sunday outing or picnic, provided another amenity for the town, and certainly helped to sustain local florists in business, not everyone thought that the change had enhanced a sense of community:

9 By their very nature, early Ontario burying-grounds left few records. Documentation of them is in part dependent on critical perceptions by the exponents of garden cemeteries and by public health officials. Nonetheless, records of at least two rural cemetery companies of Old Ontario have survived.7 These records reveal that although the winds of change did blow through rural Ontario, they had little impact on small communities. Not surprisingly it would only really be in the larger cities that fresh ideas about cemeteries took firm hold.

10 The Burgoyne Cemetery Company of Arran Township in Bruce County was founded in 1877, during the middle stages of the beautification movement; still, it remained immune therefrom and may be regarded as a traditional communal burying-ground. There was a friendly quality to the activities of those who participated in the running and upkeep of places like the Burgoyne Cemetery. When the original sale of stock in 1877 raised insufficient working capital,

11 The Burgoyne Cemetery was kept by a traditional rural means, the bee, as the company's 1909 minutes tell us:

Indeed, as late as 1942 the Burgoyne Cemetery was still very different from the "groomed" cemeteries which had sprung up around the cities; in that year "A bee was held in cemetery and grass cut after which Annual meeting was held."10

12 The Norwich Cemetery Company, located in a larger, more settled community, sheds further light on the nature and limits of the beautification movement's impact. Although its directors were aware that the ideal cemetery was cultivated, planned and attractive, they had only mixed success in achieving these goals. In 1882, they attempted to control the location and types of trees that might be planted in cemetery plots.11 In 1889 they made the first arrangements for regular grass cutting,12 and in 1898 they "inserted in the local paper, a notice forbiding [sic] bicycle riding in the Cemetery."13 Despite their partial awareness that the ideal cemetery was aesthetically appealing, they still decided to raise a barbed wire fence around the grounds in 1896.14

13 The directors were scarcely less successful as business managers. The interment of bodies in lots not wholly paid for was at first permitted, resulting in many disputes. On 1 February 1869 it was resolved and carried

Twenty-four years later, on 12 May 1893, the directors were still threatening to "evict" some lot owners and several bodies, but by January 1894 they had retreated from their socially unacceptable threats and were arranging schedules for repayment.16 In January 1915, the directors were informed by a local undertaker that the caretaker was incompetent and "crooked," trying often to "soak" people for more than the regulation price for digging a grave.17 Although the need for a perpetuity fund, an essential factor in maintaining a cemetery's appearance, had been recognized as early as the 1880s, it still did not exist in 1915. The Norwich Cemetery at the opening of the First World War remained a fairly typical, haphazardly maintained, small-town burial-ground.

14 The country and small-town cemeteries of Old Ontario tended to have a strong denominational element. Even major cemeteries in cities and towns often were connected to a church. Burgoyne Cemetery was in all likelihood an outgrowth of the Presbyterian community of Arran Township, as evidenced by frequent references in the records to Knox Church. Mount Pleasant Cemetery in London was begun by prominent businessmen from St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church. London's Woodland Cemetery is actually run by St. Paul's Cathedral; the Board of Directors includes elected members from the cathedral as well as a church warden, the rector and the dean. The Norwich Cemetery had at least strong informal ties to the Anglican community; after 1877, those buried in the "Episcopal burying-ground" were allowed to be reinterred at no charge in the potter's field of the new cemetery.18

15 Useful in determining the religiosity surrounding death in Ontario is a document in the Board of Health's records.19 This report by a district officer of health, dating from March 1922, enumerates the number, size, and ownership of nearly all cemeteries in District V, comprising the eleven eastern Ontario counties of Frontenac, Carleton, Prescott and Russell, Renfrew, Stormont, Dundas, Glengarry, Lennox and Addington, Leeds, Grenville, and Lanark. The following table, compiled from this report, demonstrates the extent to which death and burial remained an overwhelmingly religious event:

16 Fully five per cent of the cemeteries mentioned in this report were religious and of a size less than two acres; seventy-three per cent were connected to a church. By far the majority therefore must have been in churchyards. While this statistic might not be entirely representative of the province as a whole, because of the above-average Catholic population of the district and because of the propensity of Catholics to avoid non-denominational burying-grounds (any perusal of burial registers will confirm this), it is still sufficiently representative to permit the conclusion that the movement for non-sectarian, beautiful cemeteries must have been a relatively recent addition to Ontario's culture of death. Only twenty per cent of the burial-grounds were of the extra-religious types: public, municipal, owned by a cemetery company, or a "community" ground. Thus one cannot argue that the non-sectarian cemeteries were always larger and had a greater net acreage: twenty-eight per cent of the religious cemeteries and forty-one per cent of the non-sectarian cemeteries were larger than two acres. Even among cemeteries over ten acres, only eight of twenty-one were not attached to a church. Two things should be kept in mind: first, the region in question had only four substantial urban areas, Ottawa, Kingston, Cornwall and Brockville, and second, even those who might have moved to a city would still often choose to be buried in the country churchyard in the rural community that still represented the "family home."

17 Nevertheless, while death and the act of interment were strongly religious, the beautification movement challenged the sectarian aspect of burial. This was perhaps an outgrowth of the greater degree of "rational" city planning increasingly present from the mid-nineteenth century on. Rather than having dozens, if not hundreds, of small churchyards spread throughout and around the city, taking up valuable land and presenting a serious public health problem, what could have made more sense than to bury all denominations in one spacious location outside the populated area? This desire, combined with the Christian spiritual need and social impulse to assert the eternity of the soul when that became threatened by "scientism," found expression in Ontario just as it did in Boston or England.

18 While the garden cemetery represented a degree of secularization in that it discouraged burial in the ill-kept churchyards, the new, beautiful cemeteries were not without religious backing, a factor that might indicate adaptation by Ontario's churches both to the changing religious nature of the province and to Victorian sensibilities about the place of death in life. In Brockville, the degrees and progression of community adaptation are singularly visible. The "Old Catholic Cemetery" became enclosed first by a Protestant, and then, on the north side of present-day Highway 2, by a large non-sectarian cemetery; in 1893 a new Catholic cemetery was created near these three cemeteries and not on the grounds at the host parish of St. Francis Xavier Church. Ontario's first truly beautiful cemetery, the Cataraqui cemetery, commenced in 1850 near Kingston, with its sweeping, well laid out paths and roads marked by such picturesque names as Fern Path and Clover Path, was labelled as "Protestant" in the 1922 Board of Health inventory of all cemeteries in District V.20 Above all, whatever anti-sectarian claims are to be found for the beautification movement, it can be safely stated that it arose from Protestant Ontario.

19 London's Mount Pleasant is an excellent example of how the beautification movement was functional in permitting the principle of church involvement in death and burial to adapt itself to the growing cities. As a 1955 pamphlet tells us,

Woodland and Mount Pleasant Cemeteries in London, like most beautiful cemeteries, embodied this transitional religious aspect: they had formal and informal links with churches, but labelled themselves as non-denominational. Although Woodland was controlled by St. Paul's Cathedral (Anglican) in London, all faiths were allowed to bury there.22 Mount Pleasant, while integrated into the general Protestant community (as Cataraqui must have been in Kingston), proclaimed itself as non-denominational:

20 Toronto was more denominationally diverse than other Ontario cities and had larger problems regarding questions of the death of paupers, indigents and travellers. The establishment of potter's field, or the "Stranger's Burial-Ground" as it was called by Toronto businessman Thomas Carfrae and others, was a giant step towards secularization. Interments here, at the northwest comer of what is now Bloor and Yonge streets, began in 1826 and nearly seven thousand were made before the press of population forced re-interment elsewhere by 1855. Potter's field was a civic-minded project, a non-sectarian and non-profit organization, but, although graced with a fence, a small mortuary and a decorated entrance, it was little more than a field bordering on the city limits. It did, however, act as a forerunner for the establishment of the first real garden cemeteries of Toronto — those of the Toronto General Burying Grounds Trust — the Necropolis (1850), with its serene and shady view of the Don Valley, and Mount Pleasant (1871), skilfully laid out and superintended by the Cincinatti-trained and experienced landscape gardener H.A. Engelhardt. A sectarian claim to an early beautiful cemetery in the city, however, might be made by the Anglican-affiliated St. James Cemetery, designed by Toronto architect John G. Howard in 1844. Toronto, without question, would be the enduring focus of the garden cemetery for Ontario, and because of the city's size, its cemeteries would exhibit the cultural manifestations shown in large American and British centres.24

21 The maintenance of an attractive and pleasant physical appearance was, of course, a central theme in the beautification movement. Dismay over the run-down churchyard or the less than beautiful rural burying-ground was general. As was declared in a 1925 promotional pamphlet for the Toronto General Burying Grounds,

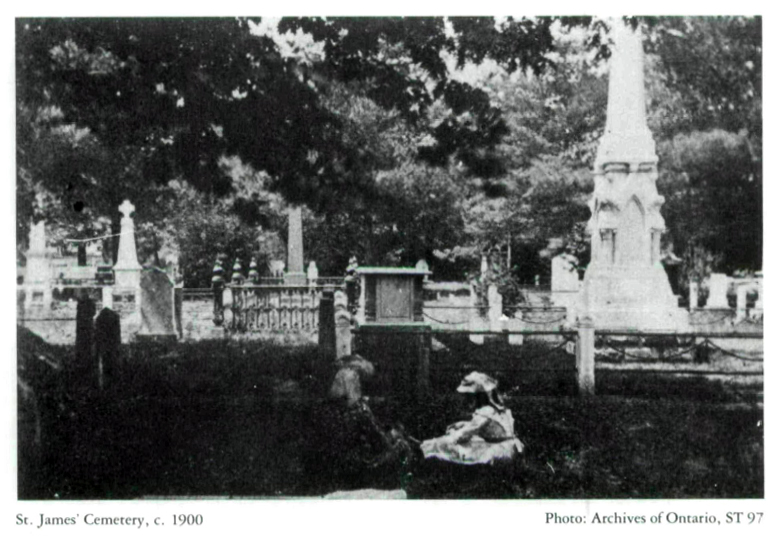

There is ample evidence that cemeteries pre-dating the beautification movement were becoming eyesores and the objects of public concern and disgust. As D.A. McClenohan, District Officer of Health for District V, informed Ontario's Chief Medical Officer of Health in 1922,

London's Mount Pleasant sought to remove the fear that one's own remains or those of loved ones would go neglected after a few years. A perpetual-care scheme was discussed and adopted as early as 1878, "to make provision for the care of...lots for all future time, so that all sections might be uniform in neatness and beauty." Five dollars would buy perpetual care, and an obligatory fifty cents annual charge was imposed on all lot holders who did not opt into the scheme.27 Toronto's Necropolis, while "not originally laid out [in the 1850s] under the perpetual care plan," adopted one as its necessity for the maintenance of an attractive cemetery became evident.28 London's Woodland established a sinking fund into which all permanent-care charges were deposited. This fund provided for grass cutting and cleaning up of plots "for all time."29

22 Important in the beautification movement was the notion of a rural sepulchre — burial beyond the city limits. This expressed both the romantic streak in the Victorian celebration of death and the more simple desire not to have the dead on one's doorstep. In 1876 those in charge of Toronto's Mount Pleasant announced that

Although many of these early beautiful cemeteries have now been swallowed up by the cities that created them, they were all originally situated just outside the cities. Not only was this viewed as desirable, it was required by law.31

23 By the First World War attitudes towards cemeteries were changing again. The park movement, which had seen the creation of a few new cemeteries before the war and the park-like development of new sections of older, established cemeteries, was now firmly favoured by professional cemetery supervisors. But the park movement could also be considered to have contributed to what some scholars have called the dying of death in the period of the First World War. The physical evidences of death, such as they were, in the form of headstones for example, were missing from the park cemetery, the design of which presented an elaborately contrived visage which served to heighten the conflicting tensions inherent in the Victorian attraction to and repulsion from death. There was supposedly little to remind the visitor of death at all. Clearly the modern attitude towards death, an event more to be endured than celebrated and usually an occurrence entirely removed from the home into the impersonal settings of hospital rooms and old age homes, followed by funeral parlour rather than parish church services, was taking hold.

24 Although rural sepulchre might have been in part a romantic Victorian vision, by the twentieth century there was also a nascent dislike of living near cemeteries that must have contributed to the exile of the burying-grounds to the city limits. They were health hazards, but they also depressed the value of surrounding real estate. Such sentiments evidently formed the basis of opposition to the establishment of a cemetery in Britannia Heights, just outside Ottawa, but too close for the liking of the wealthy suburbanites in whose midst the cemetery was to be placed. A petition in opposition was submitted to the District Officer of Health, who was legally required to advise on the suitability of the location for the purposes of interment. One sheet was even reserved for objectors, who, in 1922, possessed over $75,000 in real estate. In all, there were eighty objectors.32 The President of the Britannia Ratepayers' Association sought the Chief Medical Officer of Health's support in preventing the establishment of the cemetery:

At a public meeting, the major objections to the proposed cemetery were aired: funerals taking place near one's residence, depreciation of property by up to one third, the hazard to health, and the fact that children would have to pass the cemetery on the way to school.34 What a stark contrast this represents to the earlier attitudes towards burial and death, as exemplified so simply in the Burgoyne Cemetery Company, where the burying-ground was an organic aspect of the community, it being the duty of all to see to its upkeep.

25 In the Christian tradition, the soul never dies, only the body. At a time when this was generally accepted, the immortality of the soul was seldom asserted. But once the dominance of this Christian theology was questioned, as happened as the province industrialized and urbanized, the ideology was asserted more and more aggressively.

26 What distinguishes the beautification movement from the cemeteries of Old Ontario is not the degree to which death was seen as a religious event, but the general socio-economic context in which the culture of death was unrolling. In the pre-beautiful burying-grounds, it was not as necessary to assert one's presumed immortality with one of the ten-foot obelisk headstones which can still be seen today in the province's early beautiful cemeteries; rather, the immortality of the soul was never challenged. The assertion of death and of immortality emerged only as the province secularized; but one must never accuse the beautiful cemeteries of being secular, only of being non-sectarian.

27 Sectarian religion was not necessarily the dominant context for death in the nineteenth century. Changes in attitude towards death resulted, as is shown by the evolution of cemetery design, even more substantially from the impact of growing urbanization. It is this urban context, the early development of the anonymous industrial and multi-service city, and the threats therein contained for established familial and social patterns, that should reveal the real relationship of death to Victorian Ontario society. Likewise, because of the enormous intrinsic and symbolic importance of death to Victorian society, no study of urban industrialization can be considered complete without addressing questions of death, including, through cemetery study, the disposal of its detritus and the creation of its public reminders.

Evolving Cemeteries: A Portfolio

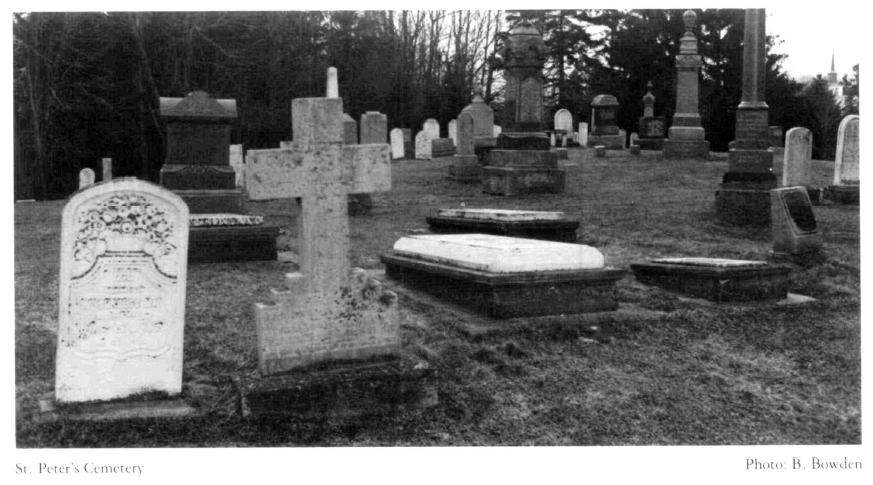

28 The mid-Victorian ideal remained the parish churchyard within sight of the place of worship. St. Peter's Cemetery in the Talbot Settlement at Tyrconnell overlooking Lake Erie is a good example, showing extended family plots, changing styles in monuments, and the adjacent interments of three generations. (Col. Thomas Talbot lies beneath the prominent flat stone in the foreground.)

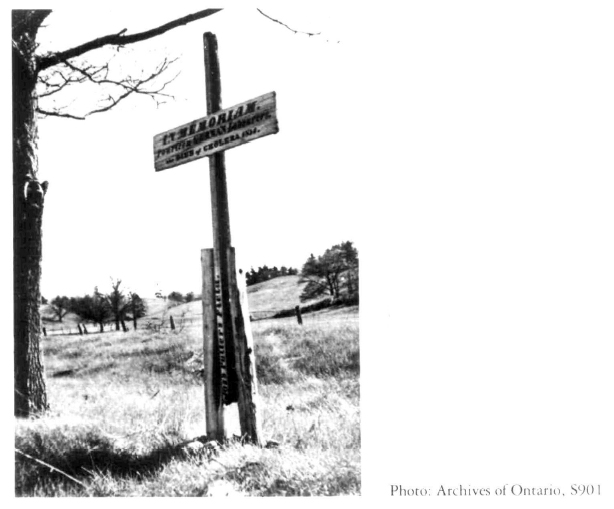

29 Frequently the small rural cemetery became a forelorn and desolate remainder by the roadside. Fate was even less kind to Toronto's first civic burial place, potter's field, at the corner of Bloor and Yonge streets. An evocative reminder of both fates is shown in this 1948 picture of a memorial, taking its name from Toronto's potter's field, which marked the burial mound of German labourers on the road between Cobourg and Peterborough.

30 In smaller, well-settled towns, the transplanted English churchyard exemplified the integral role of the church in the community. Local residents still term this Anglican Church in St. Thomas "the old English church." It dates from 1822 and was altered in 1824. Although more crowded than St. Peter's, Tyrconnell, new burials still occur.

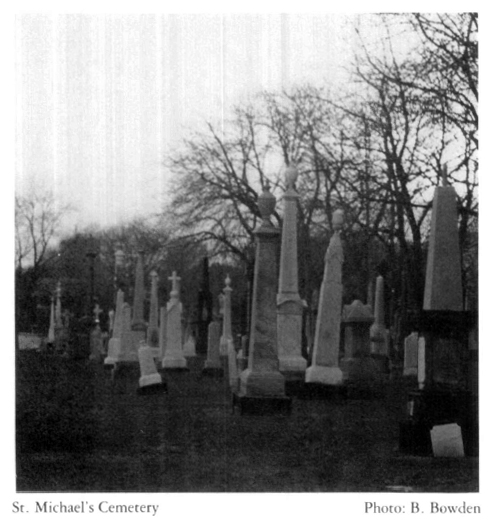

31 In the cities, however, land pressure made the ideal of the parish churchyard unrealizable. St. Michael's Cemetery, established in 1856 near Yonge Street and St. Clair Avenue in Toronto, is far from the downtown cathedral. The parish cemetery, built outside the city, has the charm of age but not of the churchyard. Its spikey verticality in irregular rows is an excellent example of the visage which later garden and park cemeteries wished to transform.

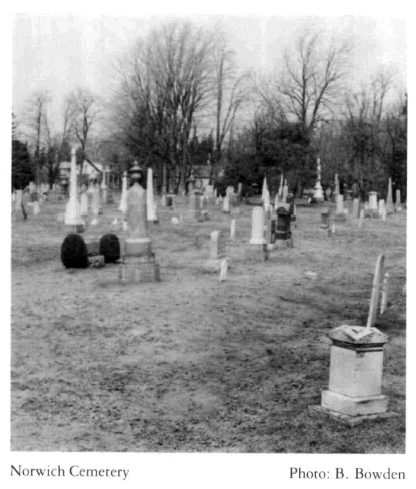

32 Many small towns were not endowed with large churchyards. Such was the case for the 1810 Quaker settlement at Norwich in Oxford County. The initial gravesite was replaced by the Quakers with a picturesque country burial-ground and meeting-house (demolished in 1946). The solution for the rest of the town was the Norwich Cemetery Company, located on the south bank or a stream, two blocks from the main intersection. The town has spread around the commodius burial-ground; the barbed wire fence is gone, and large monuments, although present, do not assault the horizon. Whereas St. Michael's Cemetery is given a claustrophobic, hemmed-in atmosphere by its monuments (let alone by the city's nearby towers) and became too small almost in one generation, this community plot suggests continuity, security, space and a relaxed atmosphere. The picture also suggests why this intermediate stage between the churchyard and the garden cemetery was aesthetically wanting to Victorian cemetery designers.

Display large image of Figure 6

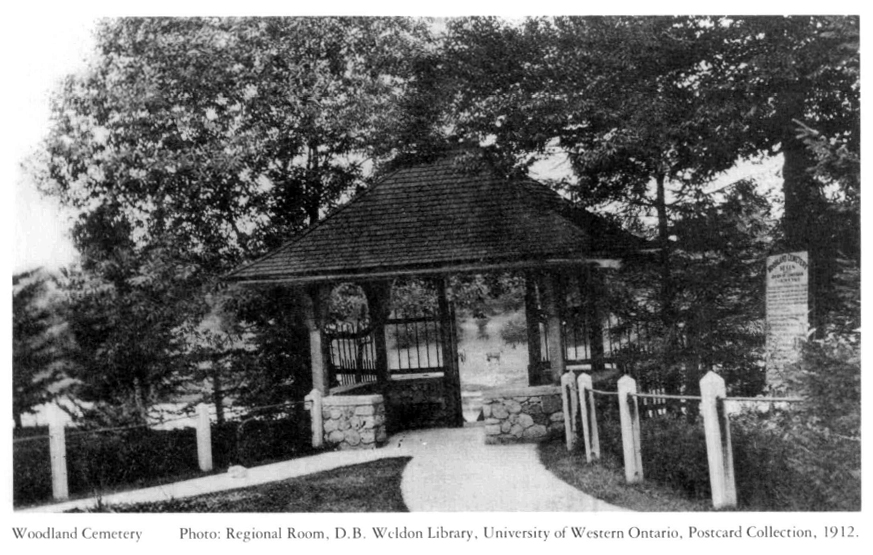

Display large image of Figure 633 London's Woodland Cemetery (at times mistakenly called Woodlawn) is more formal, possesses burial sections, a crematorium and chapel, and at one time this attractive gate, featured on postcards, through which visitors entered when arriving by boat along the Thames River. (The gate has since been demolished and the river entrance blocked off.)

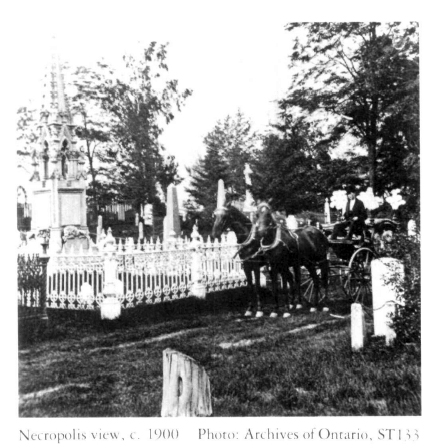

34 Toronto's Necropolis still possesses the handsomest cemetery gate and chapel in the province. Although not designed by a landscape architect, the interior views are in keeping with the churchyard atmosphere which the chapel's architect, Henry Langley, in 1872, had sought to evoke. Not only do modern photos show the continuing success of this goal, but this turn-of-the-century view demonstrates how the Necropolis was the perfect restful and romantic garden with a horse-drawn, plumed hearse in attendance.

35 The garden cemetery was the place where Victorian Ontario's celebration of death was most perfectly portrayed — where the living and the dead co-mingled comfortably as exemplified by a striking 1890s photograph from St. James' Cemetery in Toronto.

Display large image of Figure 10

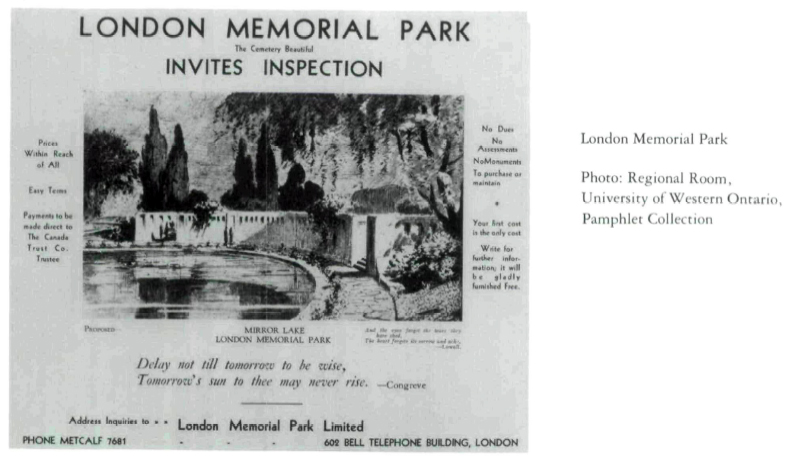

Display large image of Figure 1036 The Necropolis and St. James did not adopt the rigid decorative artificiality of the American park cemeteries. However, the proposed fountains, ponds, memorial walls and temples which were displayed and extolled in the advertising for the London Memorial Park in 1930 offer a glimpse of the elaborate denial of death which was an intrinsic component of the cemetery park conception.