Reviews / Comptes rendus

New Brunswick Museum, 144 Years Proud: New Exhibits at the New Brunswick Museum

Introduction

1 The grand old lady of Douglas Avenue has her "dancin' shoes" on. Those who might have thought that Canada's oldest museum would settle into a type of genteel dotage will be amazed at the sprightliness of her jig. The New Brunswick Museum is showing every sign of becoming one of the nation's most effervescent museological institutions. Readers of Material History Bulletin will be familiar with the work of various staff members who, for a number of years, have shown energy and creativity in the field of material history. Some may also be aware of the thoughtful historical reinterpretations presented in such exhibits as "On the Turn of the Tide, Ships and Shipbuilders 1769 to 1900." But, tight budgets tempered programming efforts. Recently, however, circumstances have improved with the result that the museum has undertaken a number of important projects in collections development and a major overhaul of the exhibit galleries.* Also the search is now on for a new exhibit facility near the Market Square heritage area to bring the museum more into the mainstream of daily life in Saint John.

2 One impetus for renewal came from the various bicentennial celebrations marking the arrival of the Loyalists (1783), creation of the separate colony of New Brunswick (1784), and incorporation of the City of Saint John (1785). A comprehensive programme of replacement of exhibits in the various history halls was begun in the later 1970s and culminated in the opening of four major galleries last year. Despite the fact that some work remained to be done, public acclaim was widespread. Visitors found a new look: an uncluttered inviting lobby, spacious exhibit design and tasteful presentation of numerous unusual items from the collections. An extensive thematic treatment of the province's history occupied the second floor display area, while artifact-rich exhibits of New Brunswick's material culture were located on the ground and basement levels. Sharing the ground floor was a hall devoted to the treasures of other civilizations, from Arctic Canada to Tibet. An indication of the energy currently driving the exhibition process is the displacement of this original display of treasures, described and analysed below, by a new exhibit, "Chinese Art," a move perhaps foreshadowed by one segment of the earlier exhibit (fig. 1).

3 Equally striking is evidence of the active debate currently underway within the New Brunswick Museum about the significance and treatment of artifacts in a museum setting. In developing "On the Turn of the Tide" considerable energy was invested in crafting a storyline that represented current research findings on a subject often obscured by myth. Artifacts were selected to complement and to illustrate this information. The result was an exhibit that taught and interpreted history. The new historical overview, "Foundations: The River Province" is in this tradition. The other halls are markedly different. In "Treausres," "The Great 19th Century Show," and "Colonial Grace: New Brunswick Fine Furniture," information and interpretation are kept to a minimum. The object is left to speak for itself. Debate over the artifact as a unique document of culture or an example of cultural process is clearly revealed in the exhibits. The obvious difference of opinions adds variety to the museum as a whole and provides interest to those who are actively following the debate.

4 A similar divergence of views is found in the comments which follow. Stuart Smith in a survey of the new halls, suggests that the role of museums is "to collect, preserve and explain what objects are and how they relate to earlier, later and even alternative creations." How objects contribute to the interpretation of a culture is "questionably a museum responsibility." Other contributors are clearly looking for interpretative guidance from the exhibits. Thus, while the following roundup of reviews is a tribute to a significant event on the national museological scene and an assessment of that achievement, it is also an independent contribution to the debate on the role of human history museums and the nature of material history.

Overview

5 When it comes to exploring the world of museums, I find my imagination dominated by two experiences. The first occurred 20 years ago in Regina. I was a first-time instructor in art history at the University of Saskatchewan, Regina Campus, and, exhilerated by the prairie experience, my wife and I were in the habit of taking long, rambling walks. In the process of one such long walk, we encountered the RCMP Museum: a longish, rectangular room with waist-high cases about two feet deep all around the outside wall and back to back down the centre. There before us was displayed the history of the RCMP as layered and varied as time itself. The exhibition technique was very simple; the earliest material was placed in the cases and as time passed and events occurred, the new material evidence was placed on top. One case in particular I remember as having a Russian machine pistol (Korean War souvenir), part of a bank robbery in British Columbia in the late 1950s, and peeking out at the bottom of the pile was the printed account and souvenir noose from a hanging in the 1880s. I know what I know about above ground archaeology from that case.

6 The other experience is Italian. From my childhood I have found the appeal of Pompeii and Heraculaneum irresistible. The idea of breaking through volcanic crust into the interiors of houses still furnished, still occupied, excites me even now. It was, therefore, with some heightened degree of anticipation that I bore down on the archaeological museum in Naples for the first time. Here was treasure trove indeed.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 17 Unfortunately, my first footstep in the building triggered a wildcat strike of guards. I was able to look into rooms filled with inaccessible goodies, while grumpy guards blocked the galleries, read their newspapers, and muttered things about society and worker solidarity. Those few rooms I was able to penetrate were filled with the looted material from Pompeii. Isolated, out of context, unexplained, it sat on shelves or in cases as remote from its contextual meaning as if it were in Houston.

8 Both personal experiences are destined for my memoirs where they will compete for attention with my notes on life with Lady Beaverbrook, but I include them here because they bear on the nature of material history and the role of the object, the museum, and the historical process.

9 The case at hand is not Regina nor Naples, but the New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, an institution with which I have had a working relationship for over eighteen years. In that time I have come to an appreciation of both the richness of the collection and the appalling conditions under which its staff have worked to discharge their commitment to history. The present displays are subject to individual assessment by others, and I will not try to second-guess their impressions, but there are some considerations of a general nature that I would like to make on the displays and on the study of material history.

10 The New Brunswick Museum building is a difficult one to deal with, a relic of the monumental phase of museum construction, but it does provide an entrance lobby of generous proportions with what would amount to two large galleries to left and right. The exhibition, "Treasures," is on the left and "The Great 19th Century" is on the right. An expansion project of a decade ago resulted in a box-like new wing, unhappily connected to the "19th Century" gallery, and functioning as three stacked galleries each dominated by freight elevator doors and dead-ended in terms of visitor traffic. An imaginative architect looking at the spectacular site of the building would weep at opportunity lost. Within the main building the basement floor is given over to the natural history exhibits, and the upper floor now houses the new exhibition, "Foundations: The River Province." The present distribution of space is that "Foundations" is a thematic or interpretive exhibition and, excepting for space given to travelling exhibitions, the remainder are displays of museum possessions.

11 The original business of museums was, as now, the acquiring and preserving of material history. More recently, as museums became public institutions rather than private enthusiasms, they have been preoccupied with interpreting that material history and, in the process, find themselves endeavouring to explain two things at once. The problem is like that faced by art historians who define the Renaissance through the description of works of art and then justify the works of art by their adherence to a Renaissance chronology. Spinning in a circle can make you quite dizzy.

12 Properly speaking, the first and obvious museum ambition is to collect, preserve, and explain what the objects are and how they relate to earlier, later, or even alternative creations. By those standards, both the RCMP and the Neopolitans had at least part of it right. The second attempt, and it is questionably a museum responsibility, is to have those objects, so carefully collected and preserved, contribute to the interpretation of a culture.

13 The first task is fundamental. It has to do with the gathering of evidence, but, as in a court of law, evidence is not all of equal value. It must be sorted, assessed, and finally put in a logical and persuasive context. Within the legal system that process also marks a transition of responsibility. At a certain point evidence ceases to be a police responsibility and becomes a lawyer's responsibility. Within the museum world that point of transition is not always clear and many modern museum practices have obscured it even more.

14 The excessive emphasis many North American museums place on their interpretive or, as more simply perceived, their teaching role has diverted scholarly attention from the study of material history and distorted the balanced product of analysis and synthesis of scholarship with a packaged presentation geared to a specific audience. The plywood and plexiglass labyrinth of the modern museum display with its many sound, light, and moveable aids is as much an indication of a problem as it is a solution. The museum world and the scholarly world, which should be one and the same, have both become seriously disjointed and, in their separate realms, have neglected many of their basic tasks. Within universities, failed academics embrace administrative tasks and values, talking with pathetic earnestness of physical plants and computerized library and administrative systems to make their world separate and secure from scholars whose messy and unsystematic nineteenth-century use of books interferes with what is held out to be modern professional library usage. Within the museum world we spend more on the bureaucratic control and supervision of our museums than we do in fundamental and lasting works of collecting and interpreting. Basic questions of scholarly function and responsibility within the museum have not been attacked because there is no clearly understood context.

15 Material history — the artifacts — are evidence, but they are not witnesses. They cannot, unaided, speak as clearly and completely as some of us would hope. In a museum, unlike most books, there must be a complete and coherent use of objects. Labelling, a part of the process of identification and interpretation, must be based on the objects, must grow from the objects. Anything else reduces them to illustrations. Part of the museum problem lies in the fact that there is, as yet, no established system of artifact analysis. Interpretation is held to be a curatorial or scholarly function, but recording the facts and administration are registrars' functions. Since the required facts are not certain, no one has yet established a system of registration that is a workable scholarly tool. The computer-based data bank is junk and without merit as a scholarly tool because no basic decisions were made about what information is important and how it is to be used. One would hope that a new generation of museum professionals would solve that problem and link the process of registration to the first stage of scholarly investigation, and in this context, the publication of research in artifact analysis conducted by graduate students in the material history program at the University of New Brunswick is to be hoped for at an early date.

16 The process of interpretation in museums is, however, still firmly linked to the interpretive or thematic exhibit, and that linked again closer to show business than to scholarship. Museum realities, particularly for American museums, are display realities. To do it they have created the simple, functional solution of the team approach, based, I assume, on the model of the American army tactical team. Typically, the museum display begins with a theme or storyline invented by one person, artifacts to illustrate it are selected by another, presentation techniques created by another, and printed material written by yet another. Would any historian write a book this way? Is any original contribution to scholarship possible this way?

17 Material history is the basic business of museums. Material culture in the sense that objects can be seen in a complete context is the business of scholars. Whether or not museums contribute to scholarship or are only what a library is to the historian depends very much on decisions made within the museum community. The difference between the museum curator and the academic historian should only be in the type of evidence they handle. Their goal as historians should be the same. The major disadvantage the museum curator struggles with is as I previously said: there is no generally accepted technique or system of analyzing the artifact and inevitably the artifact becomes an illustration rather than fundamental working material in the scholarly thesis even in the museum.

18 Some museums in North America, mostly those with wide-ranging collections, have returned to a nineteenth-century technique for at least part of their collections. The study collection (in my day at the National Gallery a euphemism for storage) is where the museum began. You attempt to collect all the examples of something and bang them in a case. That is basic antiquarianism. The scholarly use of that material is in the linkages and the relationships suggested by the material itself. The exhibition theme that grows from the objects to embrace a segment of real life is creative, museum-based scholarship. Convince me as a viewer of the validity of the evidence and the case is proven to an audience. The problem remains, however, that many museum workers today are not convinced themselves. They lack the basic skills and those skills are scholarly, interpretive skills, not display techniques.

19 Happily, that does not seem to be the situation at the New Brunswick Museum. The present arrangement of exhibits is sound in that one is immediately, on entry, surrounded by objects. They are there for us to examine close up, to ignore, or simply to take delight in. This is the point where curatorial expertise is crucial. The objects must be well chosen, particularly in the decorative arts; they must be the most intriguing, the most poignant. The extraction of specific objects to enhance, to demonstrate a theme or abstract idea should follow, and despite the disruptive trip upstairs, it does at the New Brunswick Museum.

20 The incredible range of creativity and the overwhelming amount of production in the nineteenth century is best expressed by a lavish display. In "The Great 19th Century Show" the abundance of objects make that point. If there is to be one complaint about the " 19th Century Show," it must be that it is inadequately labelled. The decorative arts in the nineteenth century need a lot of explaining to a twentieth-century public. The same problem of comprehension exists with the "Treasures" exhibition. An important part of delight is comprehension, and what delights a sophisticated man with a Ph.D. in art history may not delight a general audience unaided. "Colonial Grace" exhibits a well-chosen range of what New Brunswick has contributed to the world of Canadian furniture, but it does so in isolation. The first step of scholarship is there, but the exhibition avoids the second. Here, the display technique that is valid in "Treasures" or "The Great 19th Century Show" would be visually unacceptable, but, as presented, the objects, undeniably attractive, remain isolated bits of evidence not part of an integrated argument.

21 One of the problems with the highly structured thematic display, "Foundations: The River Province," remains the inherent conflict between the artificial pace and selectivity of contact and the unpredictable, individual joy of examining the object. That tension increases as life in the nineteenth century becomes more complicated. In addition, the curatorial problem of selecting a significant object to bring focus to Acadian activities that have left no contemporary presence in modern life is very different from trying to pick two or three display items to demonstrate the complexity of nineteenth-century industrial life, the consequences of which are all around us. That process strains the limits of the thematic exhibition of the sort "Foundations" attempts to be. A painter could tell us that as the canvas expands so does, or should, the studio to accommodate it. Unfortunately for the curators involved the physical limits of the gallery made that impossible.

Treasures

22 Entering the exhibit hall to view the "Treasures" exhibit is rather like stepping back in museological time. This can be a positive or negative comment, depending on one's opinion of current exhibition and interpretation theory. The artifacts on display are a mixture of this and that from here and there; and for those already knowledgeable persons who wish to have an opportunity to see some of the decorative arts of different cultures, or the collector or researcher who wants to study certain specialized subjects, the exhibit could be most rewarding. However, for those who want to learn more either about the artifacts represented, their techniques of fabrication, or the cultures they represent, the exhibit would be a disappointment. And, for those who want to introduce their children to museums, the exhibit is probably better avoided. This is an adult exhibit.

23 One conclusion to be derived from the exhibit can be inferred from the brief text on the wall near the entry, which notes that the installation of treasures from the collections of the New Brunswick Museum was funded by the Themandel Foundation. From the wide entry one can catch glimpses of the riches waiting to be examined: art objects and antiquities from all parts of the world, from Russian icons to Japanese prints to antique pottery and glass. If there is one impression the visitor will take away from this exhibit, it is an appreciation of the range of the New Brunswick Museum's collections and the generosity of its donors.

24 Having neither storyline nor chronology, the exhibit cannot be said to have an opening display. It seems likely, however, that most visitors would first approach a case centred just inside the entrance containing an open copy of Piranesi's Le antichità Romane. This is perhaps not the best choice for such a prominent position in an exhibition of treasures: no gold, no glitter, no obvious antiquity, and no information, other than a brief identifying label. Behind the book are two teak statues from Burma, the gift of Oliver Goldsmith in 1846. Oliver Goldsmith? 1846? If ever a museum label deserved the standard movie double-take, this is it. Even in an exhibition where curators have taken a (presumably) conscious decision to eliminate all but the briefest forms of identification, provincial pride might have prompted a little more information here. The mere fact that the New Brunswick Museum existed in 1846 is noteworthy, while a gift from the prominent native-born poet, who is often confused with his even better known Irish relative, is surely worth a little more attention.

25 If the visitor continues through the exhibit in a more or less counterclockwise fashion, the next section to be entered contains Russian works of art and "objects of vertu," as they say in the Sotheby's catalogues. Most intriguing were two cases containing spoons and dishes decorated in plique-à-jour enamel, lit from underneath to highlight the transparency of the decorative enamelwork. This is a very effective display technique, although no amount of peering at the objects from every angle could reveal the nature of plique-à-jour. Was it glass or something else? This question could only be resolved by later consulting a dictionary of the decorative arts, a step not likely taken by the average visitor. Minimal labelling also identified items in a very large and colourful display of other types of Russian decorative arts from silver communion vessels to icons to porcelain eggs. And sitting quite unobtrusively on the bottom of the case is a very traditional treasure, a Fabergé Easter egg. While not one of the famous or fabulous eggs, it is probably one of the few items in the exhibit for which a four or five word label is absolutely all one needs for recognition and understanding.

26 The next part of the exhibit focuses on North American native arts: mainly Eskimo sculpture, a few items from West Coast Indian cultures, and a colourful display of Micmac quillwork and beadwork. Low light levels unfortunately did not enhance these displays of primarily dark materials, with the exception of the Micmac case which was one of three built into the back of the exhibit hall with interior lighting. (The rest of the hall is lit by overhead track lights.) In this area one of the primary advantages of the totally typological exhibit came into play. Because there is no storyline or historic progression to be followed, visitors can, without guilt, pay only minimal attention to the objects that least interest them and head directly for those they find most personally appealing. One can, for example, just take note that Eskimo sculpture is there and go immediately to a more attractive exhibit of Micmac crafts. Modern interpretive exhibits usually allow the conscientious visitor none of this freedom of choice. A story with a beginning and an end is usually being told, a path is laid down, and a missed case is often a missed chapter.

27 Continuing along the edges of the hall, the next displays encountered present examples of Tibetan, African, and Polynesian arts and crafts. One large case is devoted to masks from Africa and the South Pacific, and another contains a rich display of material from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Tibet. It is difficult to rate the "treasure level" of the objects here, although one can assume their exotic origins and probable scarcity in Canadian collections were the selection criteria used. It is in fact now clear that nowhere in the exhibit will a justification be found of why the items shown are treasures. It would have been most helpful to have had a simple statement available, on site, showing the reason certain choices were made. Sheer monetary value is evident in some of the pieces, and age and rarity must certainly have been a factor in choosing others, but the importance of the artifacts is by no means self-evident.

28 A large selection of Chinese, Japanese and Korean artifacts filled the next section of the hall, and their juxtaposition provided a welcome opportunity to examine some evident contrasts among these cultures. The Chinese artifacts seemed to be more numerous and colourful, although this may again reflect personal preference, with three magnificent robes mounted high on one wall serving as focal points for the entire Oriental area. The robes are unfortunately unlabelled, but I believe from their location they must be Chinese. The remaining free-standing cases in the hall contain selections of pottery and glass from Ancient Egypt, Syria, Greece, and Rome.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 229 There is an old saw about speech-making that has occasionally been adapted to exhibit preparation: "Tell them what they're going to see, show them, and tell them what they saw." It is unfortunate that the curators of this exhibit chose to follow only the middle part of this instruction and left all interpretation to the viewer. Without further guidance, it is quite likely that the visitor will leave thinking that he saw a lot of "things" worth a lot of money but without remembering what he saw or under-Standing why it was in this exhibit in the first place. And since these are really not very important questions in the life of most museum visitors, another small opportunity to pass along a little intriguing information has been lost.

Curatorial Statement: Treasures

30 If it be admitted that the essence of good art transcends the time and circumstances of its creation, then our museological infatuation with order, almost invariably expressed as chronological sequence, is superfluous, if we are indeed interested in the essence of human creativity. The imposition of temporal order on the timeless, enforcing a consideration of quality in terms of an implied hierarchy of civilization, is the result of the modern museum curator's unthinking adherence to nineteenth-century popular misconceptions of scientific theories. The curatorial passion for putting the science back in Kunstwissenschaft (science of art), and order back in Kunstgeschichte (art history) often obscures the revelation of the essence of good art and design. The mad rush to meet a mandate to interpret collections through supposed effective pedagogical formulae has levelled museum displays to such an extent that differences exist only in the quality of the material exhibited and in such irrelevant things as colour of walls and content of labels.

31 Under the handy rubric of "Treasures," which as a cliché in the museum world is virtually meaningless, we assumed almost infinite curatorial licence in creating an eclectic "collections cabinet." Restrained marginally by public expectation, we operated under the principle that anything good to look at was grist for the treasures mill. Unfortunately chronological and geographical pseudo-imperatives influenced our exhibit as, for some reason, we felt impelled to separate a Piranesi engraving from two Tibetan lama's aprons and remove a Ming Buddha head several paces from a vitrine of Micmac and Malecite quillwork and beadwork. Our defence against good taste and separation of disciplines was not strong enough. We tried very hard to integrate into the gallery a cabinet of stuffed exotic birds, which are wonderful examples of the art of taxidermy, but eventually they were ostracized and returned to the natural science ghetto. We justified this act with the excuse that the cabinet of birds did not fit the uniform design of cases and vitrines. We admit that our effort at eclecticism in assembling treasures or near treasures was not entirely successful. If we had kept to the premise that things exhibited be sensually stimulating and completely ignored modern concepts of taste and intellectual order we might have been more successful. Perhaps we should have set up the gallery along the lines suggested in the useful book Norman Stiles and Daniel Wilcox, Grover & the Everything in the Whole Wide World Museum (New York: Random House, 1974) and established our criteria for the contents of the gallery so that our only rules were that the things exhibited must fit in cases, sit on pedestals or hang on the walls.

The Great 19th Century Show

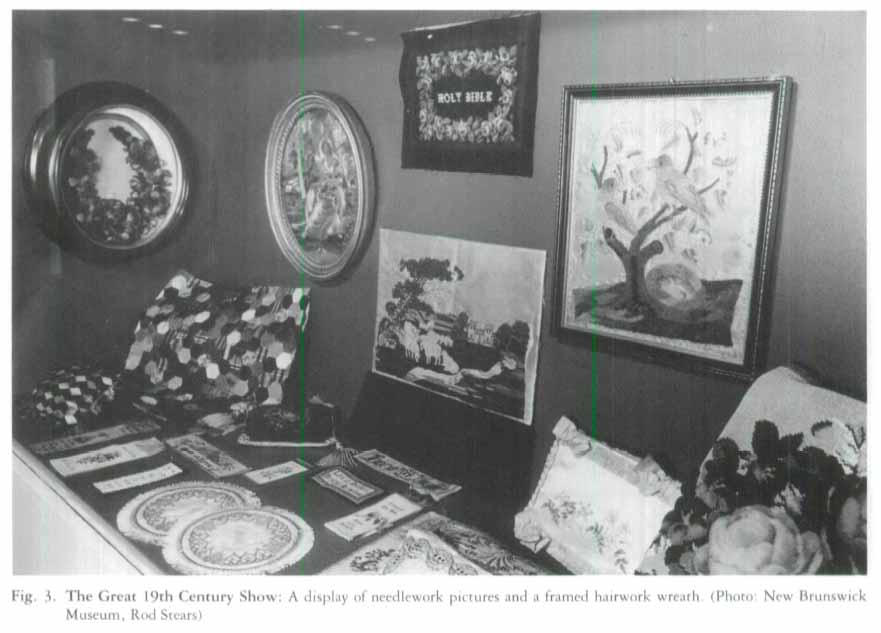

32 "The Great 19th Century Show" aspires to be a permanent exhibit of material from the collections of the New Brunswick Museum. As such, it will bean important contribution to notions about our cultural heritage, and so bears close examination. Curator Valerie Evans has conceived and developed the exhibit thematically and has had to cope with the almost inevitable limitations on time and resources. Each case, and one open display, attempts to present a microcosm of some aspect of Victorian life in New Brunswick - from childhood through mourning. When finished (target date for completion was April 1985), the exhibit will be supplemented by leaflets discussing in some depth how attitudes are reflected in the artifacts, and what the collections of objects reveal. At present, without the aid of explanatory notes, one is left undisturbed to draw one's own conclusions.

33 The title of the exhibit suggests an assault on the visitor's eyes by a riotous carnival of material culture, but what is actually delivered does little violence to the stereotype of a staid and somewhat cluttered Victorian lifestyle. A sense of the important changes that were taking place is so muted as to be almost non-existent. Thus while excitement over changing technology, "progress," does creep into the exhibit in the form of "a scientific toilet preparation" (toothpaste), and a hair rejuvenator and dandruff remover "sold under an absolute guarantee," these items are almost buried in a case of pitchers. One suspects that this results more from the museum's collections policy than from a judgement of what is significant about nineteenth-century life.

34 The problem of demonstrating change is compounded by the curator's tendency to display finished artifacts without also showing the tools that created them. Several of the cases, for example those containing beadwork, needlework, woodwork, and silverware, could have benefitted from this kind of supplement in order to produce a more balanced representation of life (fig. 3). Indeed, aside from the laundering equipment, including washboard, wringer, iron, ironing board, etc., displayed in one case, one might be tempted to assume that labour, as represented by implements of work, was of only peripheral importance to nineteenth-century New Brunswickers. This seems incongruous not only because of the contemporary development of the Protestant Work Ethic, but also because of the impact industrialization was having on provincial artisans. Though there is ample documentary evidence of a heightened awareness of work relations and working conditions,1 the changing nature of the nineteenth-century workplace is given no recognition in "The Great 19th Century Show." A further point may be made about the display of women's dresses: all were designed for miniscule waistlines, but there is not a corset in sight (fig. 4).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 435 "The Great 19th Century Show" focuses heavily on that part of New Brunswick society that could afford Malaga grapes and champagne for a St. Patrick's Day feast. While this limits the scope of the exhibit's interpretation, there are some important insights offered which, recurring as they do in several cases, deserve highlighting in the leaflets. For example, the strength and pervasiveness of social controls first appear in the case on children. A china doll in a wedding dress sits not far from an exercise book in which a child practising hand writing has repeatedly set down a moral maxim on the value of kindness. A theatre advertisement in the paper display notes in small print both that ladies unaccompanied by gentlemen would not be admitted, and that "good order is expected and will be rigidly enforced." The mourning case depicts the appropriate response of the bereaved, displaying not only widow's weeds but an ornamental pitcher showing a woman and children prostrate with grief. The concrete evidence vividly demonstrates both the subtlety and power of the Victorian moral code. This is in keeping with Brian McKillop's suggestion that "a central and continuous element of Anglo-Canadian intellectual life - so much so as to constitute a virtual imperative - has been its moral dimension."2 New Brunswick is thus placed within the mainstream of Victorian culture. What is less clearly depicted are those ways in which New Brunswickers differed from other Victorians. There are few artifacts displayed which the layperson could definitively identify as originating in the province. Even the wording on a wall tapestry is modestly Shakespearian: "We are such stuff as are dreams made of." Is this evidence of a "colonial outlook"? Would this bias be less marked if the material culture of working-class New Brunswickers had been more closely incorporated? Does the material evidence suggest an Acadian life-style indistinguishable from that of Anglo-New Brunswickers?

36 It is to be hoped that many of the questions raised by a viewing of "The Great 19th Century Show" will be addressed in the planned leaflets. As well, changes in layout and content which are planned by the exhibit's curator may do much to fill in some important gaps that remain. There is certainly much to be said for the presentation of the artifacts: They are unencumbered by bulletin boards identifying and explaining the significance of each artifact in six different type faces. The objects themselves, individually and collectively, provide imaginative access to a part of New Brunswick's heritage. But if the central imperative of historical interpretation is to explain change over time, the exhibit as it stands has not yet successfully grappled with its subject matter.

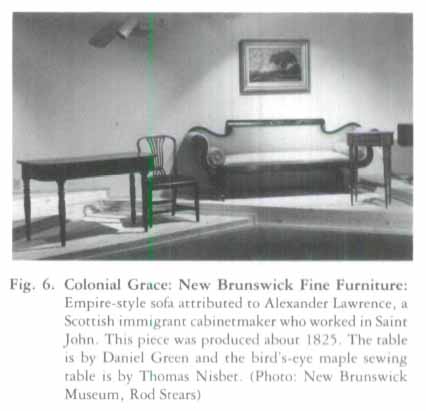

Colonial Grace: New Brunswick Fine Furniture

37 This exhibit displays New Brunswick furniture produced from the late eighteenth century to the third quarter of the nineteenth century. It was organized by curator Darrel Butler in a series of eleven groupings with a minimum of other artifacts to show the chronological evolution of furniture produced in New Brunswick (fig. 5).

38 The curator's first subtheme for the exhibit was to display furniture from the collection of the New Brunswick Museum which has been documented as made by New Brunswick cabinetmakers or which demonstrates characteristics of New Brunswick-made furniture. The characteristics of New Brunswick furniture are well demonstrated in the exhibit, although at the time of viewing neither exhibit text nor an accompanying leafier explains how these characteristics are recognized.

39 The exhibit relies heavily on attributions made by persons in the past in linking artifact and artisan. The only furniture that can be identified as made by, or attributed to, a particular cabinetmaker are those marked by the cabinetmaker either by a label, brand or stencil; those for which a family history or documentation exists; or those for which sufficient characteristics determined by study of known pieces exist to allow an attribution. Forty per cent of the exhibit meets these requirements. Three pieces are labelled - two by Thomas Nisbet and one by Daniel Green (fig. 6). Approximately fifteen other pieces have sufficient documentation or characteristics to warrant attribution. The balance of the furniture might better have been listed simply as New Brunswick furniture, omitting some of the attributions settled on them over the years without extensive substantiation. Also, there are a number of labelled, branded or documented pieces of furniture in the New Brunswick Museum collection which might have been included as meeting the requirements of this subtheme, such as a Windsor chair branded by John Dunn, a Windsor chair branded by Charles Humphrey and two card tables labelled by Thomas Nisbet.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 640 An ideal opportunity was missed to group together pieces in the collection that were fabricated by Thomas Nisbet and connected to him by attribution or label. Recent research has documented sufficient construction characteristics from labelled pieces to attribute some of the furniture in the exhibit to Thomas Nisbet regardless of previous attributions; for example a soft table in fourth setting, a sofa in tenth setting, and a card table in eleventh setting. A room setting featuring Thomas Nisbet's work both labelled and attributed would seem appropriate as he is the best documented and most widely known New Brunswick cabinetmaker at the present time.

41 While the exhibit succeeds in presenting a generous array of New Brunswick furniture, the second subtheme of displaying the chronological evolution of furniture style in New Brunswick is less well met. The furniture in the various room settings overlap several styles so that the evolution of style is not as obvious as would be possible with groupings spanning fewer years and styles. For instance, the second and third settings include Hepplewhite, Sheraton, Regency, Empire and Chippendale styles spanning dates of production from 1780 to 1845. The fact that the furniture settings are not situated in a chronological sequence around the exhibit room also detracts from this subtheme. As a person enters the exhibit, the settings begin on your left and continue clockwise to the fourth setting. At this point, there is a break which requires moving to the last setting and then counterclockwise to follow the sequence. The requirement to do this in order to follow the chronological sequence is not indicated in the leaflet or in the exhibit itself.

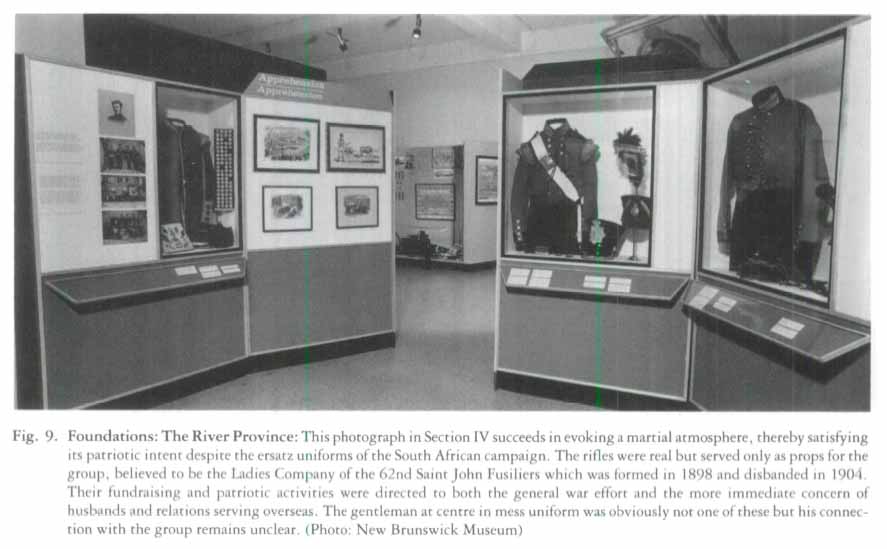

42 "Colonial Grace" employs some interesting display techniques, some of which work better than others. Rather than use exhibit captions, an illustrated leaflet is provided. This is an asset since captions would disrupt the visual effects of the exhibit. The information provided is quite brief, however, and contains several slips such as calling a card table by Thomas Nisbet in the second setting a dining table or indicating that the D-end portion of a large dining table by Daniel Green is a table. The furniture settings are exhibited on modern platforms which are unpainted new wood and which detract somewhat from the exhibit. The visual effect would have been enhanced by either painting or covering these platforms. Since much of the furniture is made of mahogany, it is necessary for the exhibit to be well-lit. Several of the room settings are not well-lit so that it is difficult to see the details of the furniture.

43 The most important, and not inconsiderable, contribution made by this exhibit is that it displays for the first time a major portion of the furniture holdings of the New Brunswick Museum. Also, it includes many other pieces that have not been displayed, at least in recent years. The Museum and its guest curator, Darrel Butler, are to be commended for illustrating the range of furniture made by New Brunswick cabinetmakers.

Foundations: The River Province

44 "Foundations: The River Province" is the umbrella title for a six-section exhibit launched in June 1984 by the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John to celebrate the province's bicentennial. Robert Elliot and Gary Hughes both of the Museum's Department of Canadian History were the principal organizers. Mr. Elliot also served as project coordinator.

45 Three years in preparation, pre-launch discussions included meetings with historians from the University of New Brunswick in Saint John and Mount Allison University in Sackville, whose most recent works helped to define the scholarly perimeters of the exhibit. Also held were consultations with the museum's Education Department regarding concept development. Following these and subsequent planning sessions characteristic of a jointly organized project, Elliot and Hughes decided to produce an artifact-intensive exhibit based on current New Brunswick historiography and the museum's collection. Design and presentation were developed to appeal to as broadly based an audience as possible and to diminish instances of visual boredom. In these goals they appear to have been quite successful.

46 In its planned dimensions the exhibit is too intensive and extensive to be absorbed on one visit; thus the curators have wisely chosen to organize this visual panorama of provincial history into six integrated mini-exhibits, each of which is intended to, and does, stand alone. The theme, which relates one section to another and all sections to the title, is the continuous interaction between man and his environment from circa 1600 to 1900. To "marry" the archival and material dimensions of the past visually is always a curatorial challenge. Similarly so in this exhibit the organizers were charged with selecting appropriate points in time and space that best illustrate the general theme and choosing artifacts to complement and enhance conventional wisdom, while at the same time nudging the visitor's assumptions about the past.

47 The preliminary introduction to the exhibit preceding Section I, includes an oil painting of Grand Falls, New Brunswick (c. 1890) accentuating the rugged terrain occupied by native peoples and European newcomers. In addition, this work by John C. Miles demonstrates at the outset the curatorial emphasis on the relationship between man and land. The display of a Maliseet (Malecite) Indian headdress and the watercolour of the interior of a Maliseet hut (c. 1860) provide a striking visual contrast to the artifacts included in Section I "17th Century Acadia." This and Sections II and III, "A Decision to Be Made" and "Birth of a Province" were organized by Mr. Elliot and cover the period roughly from 1600 to 1810. Section titles are indicated by banner labels clearly demarking each from the other. Within each section there are three or more subsections, again each clearly indicated and within the subsections, a visitor's attention is directed to particular artifacts drawn largely from the museum's collections.

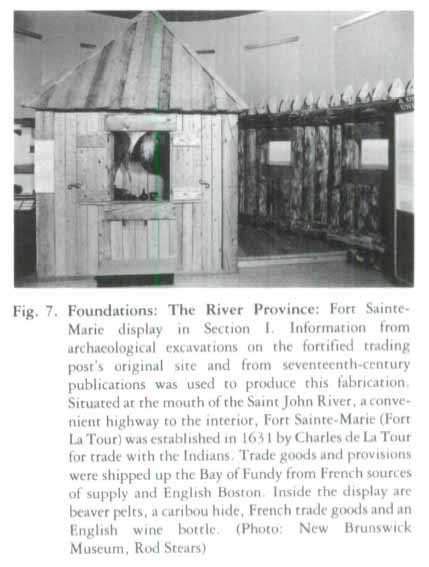

48 Section Ⅰ dealing with early Acadia contains artifacts indicative of the process of cultural transfer underway during this period. An early Bible dramatizes the differing communicative technologies and religious orientations of the Old and New Worlds. In particular this cultural contrast is suggested in the carved figure of Christ from about 1500. Through careful labelling the visitor is informed that this religious artifact from Burnt Church, Northumberland County, New Brunswick, is believed to have been given to one Peter Pelott, a chief at Burnt Church, by an early French missionary priest. Added to these most enduring religious symbols of social and material culture, Section I contains a judicious sampling of the era's portraiture captioned to reveal connections with New Brunswick's historical foundations. For example a sepia painting done in 1642 of Charles de Menou d'Aulnay (c. 1604-1650) is labelled to note d'Aulnay's rivalry with Charles de La Tour, a feud that dominated events at the mouth of the Saint John River for several years during the seventeenth century. The number of explanatory notes and variety of artifacts from this period should certainly raise the consciousness of some visitors about the pre-Loyalist history of the province. A blanket chest made around 1670, mid-seventeenth century ceramic pieces, and an iron cannon from the Portland Point excavations all form a material legacy underscoring the rich pre-Loyalist heritage.

49 This section also contains a reconstructed model of a storage building at Fort Sainte-Marie situated in the seventeenth century at the mouth of the Saint John River. The design of this building (fig. 7) was developed by Elliot from sketches of earlier such constructions, archaeological site reports for Portland Point, and consultations with others possessing expertise in the architectural history of seventeenth-century Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The reconstructed storage building conveys a sense of immediacy with its inside display of "beaver pelts, French trade goods and an English wine bottle." The curator has enhanced this effect by constructing gun ports in the adjacent palisade which help to situate the fort temporally. Positioning the gun ports to face through the museum's windows enables the visitor to look out onto the Saint John River and momentarily "experience" a sense of encapsulation within a fort.

50 During one of my trips to the exhibit a school tour of junior high students was visiting. The most enthusiastic response was generated by Fort Sainte-Marie as each student took a turn peering through a gun port facing out towards the river. It seemed that these young visitors among whom, according to their teacher, only six out of forty-two had previously been to the museum, could benefit from a guide to the exhibit. Perhaps such a guide or brochure addressed to students, tourists and local residents might enhance the profile of an exhibit scheduled to run for four years.

51 In Section Ⅱ "A Decision to Be Made" New Brunswick is placed within the series of European and North American struggles eventually determining the political fate of this region and province. Here, as in the preceding section, the storyline is chronological and the visitor is immersed visually in the portraits, maps and weapons technology of the early to mid-eighteenth century. From an historical perspective attention had to be given to events occurring in Quebec, upstate New York, Massachusetts and the areas encompassed by present-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Drawing upon a welter of events impinging upon several geographical enclaves, the curators have balanced the tone of conflict conveyed through the material culture of warfare with the domestic artifacts of the merchant/traders associated with the Simonds, Hazen and White firm and the "extremely rare" pre-expulsion Acadian artifacts. "A Decision to Be Made" is a well integrated mini-exhibit skillfully distilling the historical data, while utilizing such artifacts as a child's sled from about 1729 to re-create visually the diverse elements that can be subsumed under the term "Foundations."

Display large image of Figure 7

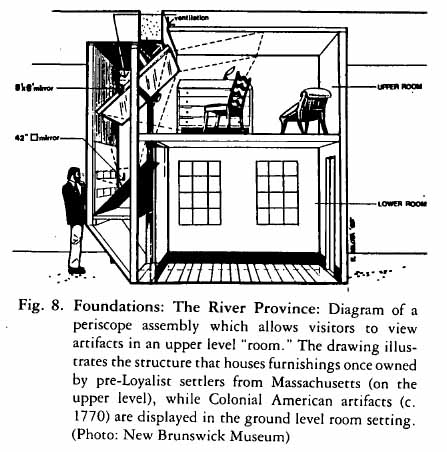

Display large image of Figure 752 In Section III, "The Birth of a Province" the time frame focuses upon the prelude to the American Revolution and the arrival of the Loyalist exiles. Again, artifacts selected place New Brunswick within the regional area anchored by Québec, Halifax and Boston. Examples of British and American colonial currency deflect the visitor from the "great issues" of the day to a more culturally and temporally transferable parallel with the present. Use of the periscope technique in designing the Massachusetts Settlers room compensates for the museum's limited floor space, while permitting an intense view of several pieces suggesting a moderately comfortable domestic life in New Brunswick (fig. 8). Portraits of those instrumental in the political and commercial foundations of the province, the Odells and Major John Ward, for example, offer individual faces to the collective human dimension of exile. The attendant confusion, excitement and anxiety of uprooting and relocating is sharply focused in the display of a single slipper identified as the surviving half of a pair worn by Charlotte Haines as she disembarked at Saint John Harbour in 1783.

53 Glimpses of exile are tempered by the curators with artifacts suggesting settled domesticity and re-establishment of familiar patterns of life. A diverse number of silver pieces and kitchen utensils underscore the building of a community. Most notable is the erection of a facsimile of the 1784 Exchange Coffee House affording a view of an architectural style employed in the late eighteenth century, while displaying furnishings and other artifacts most likely to have been present in such an establishment in about 1810. Including this reconstruction within the exhibit alerts the visitor to the dynamics of cultural transfer by underlining the speed with which institutions known in the American colonies were re-created in New Brunswick. Simultaneously the leisure and business settings of those who might be described as the elite of an emergent late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century commercial city are revealed.

54 Sections IV, V and VI focus on the nineteenth century and were organized by Gary Hughes. The organization of these sections while continuing the general man and his environment overview diverges slightly from the chronological mode employed in Sections I to III. This may be due to the direction that nineteenth-century New Brunswick historiography has taken in the last decade. The tendency among some historians to examine a selected issue or theme in a case-study approach has produced several studies both provocative in their initial findings and suggestive of further research.

55 In Section IV "The Military and New Brunswick" the visitor is made aware of the circumstances leading to the establishment of an Imperial military presence in the province and the eventual development of the provincial militia (fig. 9). A map of Europe and North America graphically illustrates the effect on New Brunswick of Napoleon's closure of the Baltic timber ports to Britain, thus contributing to the creation of a timber colony.

56 The military town plans of Fredericton 1826 and Saint John 1829 together with the displayed sashes, caps, epaulettes and shakos reinforce the early beginnings of these cities in their partial urban roles as garrison towns. The exhibit carefully outlines the historical evolution of the military's role in the province's founding, the War of 1812, the Fenian raids and the post-Confederation development of a more "reliable, permanent organization of volunteers." What is communicated in this section is the extent to which the militia touched or may have touched the lives of various groups within late nineteenth-century New Brunswick society. For example, a photograph showing a group of women each with her own rifle is believed to be the Ladies Company of the 62nd Saint John Fusiliers. Although not labelled in the exhibit it is distinctive in its portrayal of women as auxiliaries to the local militia unit containing men who served on active duty in South Africa. To the historian this photograph strikingly suggests the need for increased research on women's homefront roles before the twentieth-century wars.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 857 From a thematic consideration of the military, Section V "Immigration, Settlement and Adaptation" focuses upon the demographic outlines of provincial development. The backdrop to the European exodus is suggested in a photo reproduction of the departure quay at Cork and an emigration broadsheet from Wales. This display technique also provides a glimpse of between decks conditions on the Atlantic crossing. Most graphically indicative of the first stages of adaptation to the new land is the lithograph of Partridge Island, Saint John's island quarantine station "erected to discover and control ship borne disease." Almshouse notices of recent immigrant deaths and a broadsheet printed around 1834 for the Saint John Board of Health attest to the public health implications of processing newcomers through the port city.

58 So ubiquitous had the Irish become in Saint John and North America that by 1865 the "stage Irishman" had emerged. The curator has illustrated this nineteenth-century music hall phenomenon by displaying the words and music of "Pat Molloy." The curatorial emphasis on the Partridge Island-Irish immigrant associated artifacts, such as a child's trunk (c. 1825-50) and shoes of Irish manufacture (c. 1825-50), underscores the magnitude of Irish immigration to the city and province and provides a visual entry to the subsection entitled "The Religious Prism."

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1059 Two concise paragraphs alert the visitor to the number of Christian churches competing for adherents and, moreover, to the potential for conflict in an age when religion and ethnicity frequently marked the perimeters of social life. Modern visitors who may be less familiar than their New Brunswick forebears with the artifacts of religion and religious institutions may be surprised by the variety and quality of chalices, cups, collection boxes and communion services used throughout New Brunswick (fig. 10). This display suggesting an intensity of devotional exercise complements and contrasts with the artifacts exhibited in the adjacent subsection "The Orange and the Green." Photo reproduction of mid-century July 12 parades and riots capture the flavour of tension existing between Protestants and Catholics. The single shot 1840 percussion pistol alleged to have been used during the York Point (Saint John) riot of 1849 demonstrates the degree of violence based on religious antipathy and suggests the need for greater examination of the existence of crime and deviance occurring in nineteenth-century pedestrian cities.

60 While immigration, religion and ethnicity dominate this section, the curator has also given attention to the Temperance Movement. Artifactual remnants showing attempts to curb the use of spirits, for example a member's card and ribbon from the Cold Water Army circa 1854, are exhibited with an even more extensive array of goblets, flasks, glasses, bottles, barrels and signs used in the production, promotion and consumption of alcoholic beverages. The artifacts within this subsection suggest society's ambivalence towards alcohol and underline the need for further historical research into the nineteenth-century complexion of this issue.

61 Concluding Section V is "Education" another area still largely unresearched. Within the historiographical limits imposed on the curator, this display succeeds in conveying both the nineteenth-century evolution towards increased teacher training and certification, through the display of a teacher's licence and late-Victorian classroom materials.

62 Section VI "Moulding a Province" closes the exhibit with an overview of the impact of industrialization on New Brunswick. A photo blowup of the passenger engine Ossekeag produced at the Phoenix Foundry in Saint John in 1859 reveals at once the manufacturing impulse and transportation orientation of the second half of the nineteenth century. Numerous artifacts from the railroad era including spikes, baggage checks, coupling pins and a rail segment recall an era when modern transportation theory began to be viewed in terms of time/cost variables rather than absolute distance.

63 Complementing this increasing differentiation within the work sector of society was the emerging organization of leisure activities. Photos of a tennis game and yachts at Millidgeville suggest the private recreations available to a few. Other photos of the Saint John Hockey Club and St. Peter's Baseball team underline the growth of late nineteenth-century team sports and the underpinnings of mass spectator sports. Also included are photos of hunting and fishing expeditions, one of which shows two Indian guides with a white fisherman/sportsman on the Miramichi around 1900. These photos although not labelled are visual evidence of the foundations of tourism in New Brunswick and are most appropriately included in the subsection "The Outdoor Society."

64 Section VI concludes perhaps somewhat speculatively with the subsection "Centennial and Beyond." The focus is the Loyalist renewal and Acadian renaissance of the 1880s. Photo reproductions of book covers dealing with the Loyalist centenary celebrations and the original photograph of the "Polymorphian Grand March Forming Up for the Loyalist Day Parade" underline the sense of southern New Brunswick's Loyalist heritage. For Acadian New Brunswick it was a time to assert its provincial role. A number of the artifacts depicting the province's Acadian heritage are on loan from the Musée Acadien. One in particular, the Société L'Assumption Badges, clearly evokes the religiosity of the Massachusetts-based Acadian insurance company.

65 The display panels in the closing section of the exhibit "Foundations: The River Province" capture the overall message for material historians. The lingering impression left by these examples of cultural persistence seems to be that culture has its own evolution influenced, but not determined, by environment. The exhibit not only succeeds in presenting an artifact-rich, historiographically current interpretation of three centuries of New Brunswick history in an interesting fashion, it also addresses questions of importance to material historians.

Curatorial Statement: Foundations: The River Province

66 The New Brunswick Museum's permanent exhibition, "Foundations: The River Province," was opened on June 17, 1984, to celebrate New Brunswick's bicentennial as a province. This exhibit, which occupies the entire second floor display area in the museum's original building, is seen as part of a comprehensive plan to renew the institution's permanent galleries over the next few years. Its construction was made possible through a generous grant from the Museums Assistance Programmes, National Museums of Canada. Through the installation of "Foundations," the museum wished to provide greater public access to one of the most significant collections of Canadiana in the country, the J.C. Webster Pictorial Collection, and to display a large selection of three-dimensional artifacts. Although it was considered desirable to place as many artifacts as possible on view, the History Department also wanted to produce an exhibition that presented a series of important statements about the early history of Acadia and the historical development of New Brunswick within the Canadian context. The opening followed three years of preparation.

67 The exhibition's central theme was based on geographical determinism and the role this factor had in the development of New Brunswick. "Foundations" examines the impact of Eastern Canada's geographic location and environment on New Brunswick's historical settlement and growth from exploration to colony to integration within the national grid (c. 1600-1900). The natural resources available and the area's geographic position had a marked effect upon the human inhabitants and the development of the province. Since the area was only part of a larger stage, struggles between individuals and nations, and events that happened in adjacent and more distant locations, were presented to reveal their impact on New Brunswick.

68 Although the exhibition has a main underlying theme, the display was subdivided into six major sections designed to complement one another and arranged in a roughly chronological sequence. The individual sections are, in reality, self-contained mini-exhibits. Since "Foundations" presents a three-hundred-year slice of provincial history, we felt that the museum visitor should have the freedom to select sections that appeal to him or her and yet be provided with a reasonable amount of information about the chosen topic. For example, a school class studying the Loyalists could concentrate on Section III: "Birth of a Province."

69 Even though the history curators wanted to produce a thematic exhibition, we did not wish to fit artifacts into an established storyline. The production method that was adopted saw the development of a very general theme. The search for artifacts that would properly illustrate the selected theme was begun and lists of suitable items were compiled. Following this search the original exhibit themes were modified to make best use of the available artifacts. In one case, it was discovered that there were insufficient objects to represent a particular theme effectively. That theme was replaced. Since it was felt that artifacts should perform the role of thematic building blocks, they were allowed to denote the various subthemes and, from these, the exhibition's overall theme.

70 The curators were aware that they did not have the expertise to cover every period to be represented in the exhibition. To overcome this problem, experts from specific fields of study were consulted. Individuals from university history departments, Parks Canada, Department of Historical and Cultural Resources, Province of New Brunswick, and other institutions provided assistance and information. Once the curators had selected artifacts to represent the various subthemes, a meeting was held with a panel of university historians. They reviewed the exhibition proposal and suggested several alterations.

71 To maximize interest for both school and public visitors, a variety of exhibition techniques were employed to enhance the gallery's visual appeal and several innovations were incorporated which have been considered successful. Not only were panels, cases and room settings installed, but stacked displays constructed, wherein the bottom level represents a traditional museum room setting, while the top level exhibit is conveyed to the visitor through the use of large mirrors (see diagram of a periscope assembly, fig. 10). Panels and cases were designed to be removed with relative ease. In this way, the curators will be able to change the artifacts in individual displays on an irregular basis and thus modify sections of the gallery over time. A natural setting was also incorporated into one of the exhibits: through the gunports of the Fort Sainte-Marie palisade, museum visitors may look upon the Saint John River, one of the major highways to the provincial hinterland for the entire three hundred years examined by "Foundations: The River Province."

*Editor's Note: Two temporary exhibits designed to complement the bicentennial celebrations, "River Travel" and "Celebrate Saint John" have been omitted from this critical wrapup of the new exhibits at the New Brunswick Museum.