Articles

Dying and Rising in the Kingdom of God:

The Ritual Incarnation of the "Ultimate" in Eastern Christian Culture

Abstract

This paper maps the rituals through which devotees in Eastern Christian communities are initiated into the Kingdom of God. Its primary focus is the intimate relationship between the rituals surrounding dying, death, burial, and the memory of the dead, with the festive cycle of Holy Week and pascha (Easter), in which Christ's dying and death are contemplated. The paper argues that the mythic pattern of Holy Week and pascha structures and informs the meaning of dying and death for the devotees, the mourners, and the community. The mythopoetic character of both ritual cycles (Holy Week and pascha, and, the rites for the devotee) uses sacred word, object, and gesture to identify the devotee with the cosmic Christ. In this manner, the experience of death is wrested from chaos, and the devotee is initiated into a cosmos laden with sacred meaning.

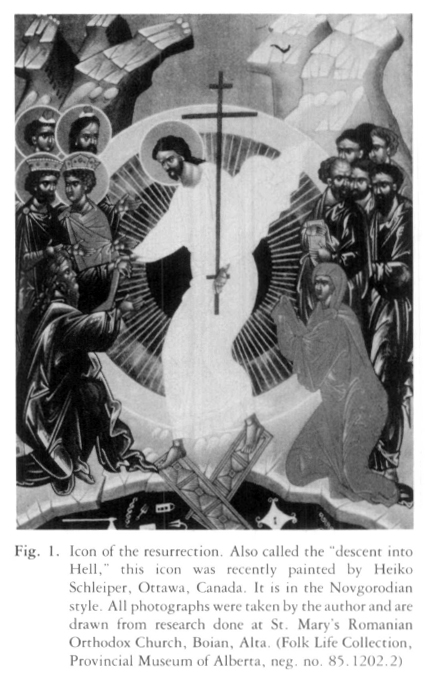

Résumé

Cet article trace le tableau des différents rituels religieux destinés à révéler le royaume de Dieu aux adeptes des communautés chrétiennes orientales. L'auteur s'intéresse particulièrement au rapport étroit qui existe entre les rituels entourant la mort, l'inhumation, le culte des morts, et le cycle de fêtes de la semaine sainte et de la pascha (Pâques) qui commémorent la mort du Christ. D'après l'auteur, la semaine sainte et la pascha constituent un modèle mythique qui structure et traduit le sens de la mort pour les fidèles, pour ceux qui portent le deuil et pour la collectivité. Le caractère mythico-poétique des deux cycles rituels (semaine sainte et pascha ainsi que les rites observés par les fidèles) fait appel à la parole, à l'objet et au geste sacrés pour identifier l'adepte au Christ cosmique. C 'est ainsi que l'expérience de la mort échappe au chaos et que le fidèle est initié à un cosmos chargé d'une signification sacrée.

Introduction

1 The concern of this paper is to explore the pattern of meaning formed by the ritual actions associated with dying and death in the liturgical tradition of Eastern Christian culture:2 its movement from mythic image in pascha (Easter), that grand universal paradigm of understanding provided by the tradition, to the ritual action in which the devotee identifies with the myth and comes to understand (to know) the meaning of the experience of death in the "fullness of its mystery." The mythic dimension (image) of dying, death, burial, and resurrection known in the religious imagination is thoroughly formed in that cycle which stands at the apex of the church calendar: pascha, or Easter.3 With its various rites and ceremonies, the mythic drama of human beings, a drama celebrated at pascha and in the rites associated with the experience of dying and death, is played out. In pascha the human experience is seen in its universality as a form of Christ's passion (suffering and death). The rites of initiation associated with dying, death, burial and the memory of the loved one are experienced with the immediate force of what is unavoidably at hand.4 The individual's experience is taken up into the universal action of Christ. What devotees contemplate through Great Lent and pascha in the life of Christ, they experience "in the flesh" in their own dying, and in the death of their loved ones. In pascha the rituals are mythic; in the initiation of the devotee to the mystery of dying and death the mythic pattern takes on the most direct human proportions.

2 The ritual action associated with dying and death will be examined, with an emphasis on the interplay of form and image between the mythic rites of Great Lent and pascha, on the one hand, and the rites of initiation for the dying, on the other. The way the mystery of death is incarnated in word, gesture and object will be the focus of this study.

The Sanctification of "the Horror"

3 When we plunge into the question of the meaning of death and dying for Eastern Christian culture, we are faced with a world view and a form of cultural making very different from what we in the West are accustomed to considering Christian. The definition of Christian has been largely appropriated by the Western Church and, most recently in North America, by Protestant culture and its secular variants. Nevertheless, we are discussing a culture, profoundly Christian, which shares with the West common patristic roots for its theological ideas. Its sensibility, its understanding of the notion or concept of creation, and its ritual embodiment of these matters are, however, so dissimilar that one is inclined to suggest that a different god is active on this cultural playground.

4 What is the meaning of death for Eastern Christian culture? How does the terrible existential reality of death inform the believer's understanding of creation, the status of the human, and, ultimately, the course of human destiny?

Death, the Abnormal Condition of Life

5 Death enters the world through sin. Sin is not, like "mortality," a structure of creation. Human beings are creatures, and thus share with the rest of creation the mortal status of creatures. They are not God, though deification is the goal of human life. What humans experience of the divine, the church fathers are fond of suggesting, is the energy of God (not his essence), a chief characteristic of which is consciousness of their creature-hood. In fact, it is through the recognition of their finitude that they "recover" the fullness of created being and step onto the path to deification. This is beautifully summed up by a favourite phrase of St. John Chrysostom: "God has become man so that man may become god." This is not a simple return to the primordial status of consciousness in which innocence is recovered — a restoration of the state before the Fall, before sin entered the world. On the contrary: it is an initiation through death, and through identification with the death of Christ, to a life in which death itself is transfigured. Death's power to destroy, to "trample down," has been redeemed, and human beings are freed to experience even their dying in the light of Christ. This is "imaged" by the tradition in the icon5 of Christ's resurrection, also called "the descent into hell," which shows his salvific action for the release of all who are enslaved to death (fig. 1). Both in the icon and in the specific ritual act prescribed in the liturgical calendar (especially in pascha, but also in the Feast of the Elevation of the Cross and others), we see the process of the redemption of death — its redemption, in fact, to the status of mortality. Mortality can be sanctified through Christ's action. Death, the curse, is transfigured when the devotee is taken up into the universality of Christ's action in the passion. Once his circumstances arc identified with Christ's passion, the devotee can give himself to the expedience of dying.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 Man's mortal life is identified with that of the Christ. In this manner it is sanctified: taken, as it were, into the Body of Christ. Those participating in the various rituals under discussion, both the dying person and those drawn to the bedside, funeral, grave or table of memory, are taken into and identified with Christ. It is "in Christ" that the fullness of human existence is realized.

7 The Christian myth is primarily about the restoring of God's creation to himself. Creation is understood to realize its completeness, the "abundant life," when unselfish love predicates experience and the destiny of lift in union with God is actualized in time. This does not lead the believer to a petition about heaven or the afterlife. The myth is not understood as being about immortality of the body and soul in any sense current in popular Western Christian thinking. Rather, it is a precise way of identifying how human beings, giving up their presumed status as "immortal" beings (demi-gods), recover all that is good, true and beautiful in life through recognition of their own finitude and through identifying with the death of God in the crucifixion of Christ. There is no sentimentality here — just a cool eye on the reality of mortal life. Here man undergoes a growing identification with the myth in which Christ, the God-man ("fully man," as the great creeds proclaim), takes on the life of all humans, its agony, its dying and death and, finally, its fullness, which is proclaimed by the tradition as his "glorious reign eternal" and is memorialized in the Divine Liturgy and explicitly enacted at pascha. The human status is restored because Christ has "taken it on Himself." Through "flesh" sin entered the world (in the sin of Adam), the tradition proclaims, and, through flesh, the flesh of Christ (the second Adam), the bondage to sin and death is lifted for those who enter into the Body of Christ. How this is accomplished is described in the next section.

The Myth and Ritual of Dying

8 The ritual of Holy Unction begins when the priest is called to the bedside of an Orthodox Christian. He comes in a flowing black cassock armed with a stole (the insignia of office) and with flasks of oil like that used in ancient times to anoint warriors prior to the "last" battle. The priest also brings chalice and paten, containing the Body and Blood of Christ. All is laid out on a table close to the suffering devotee. Here we are looking the grim reaper in the eye, armed for battle though not for victory (at least not in the conventional sense). But it is the body and blood of the devotee that focus this contemplation, that are offered up on this occasion to the Creator for what "will [most assuredly] be done." The words come quietly like distant thunder, hanging in the air for all to hear. The words are to the warrior lying unable to move, lying in wait for "the end," the end, which as T.S. Eliot says, "is my beginning."6

9 Hold this image in mind: the bed of the dying with those who surround it, the priest presiding and the medical professionals scurrying about on the periphery. A small table is prepared, covered with a linen cloth reminiscent of that swaddling Christ at his birth or binding his corpse in the tomb. A vessel is set on the table. It contains wheat, the embryo of life, specifically of that life which, having fallen into the ground, has given birth to life — a "natural" resurrection of sorts (John 12.24; 1 Cor. 15.36-38). Holy oil is placed on the table. A token of the grace of healing (Mark 16.18), holy oil is the focus for this service. A gospel book, lighted tapers and seven wands wrapped with cotton for the anointing are thrust into the wheat. The priest, vested in his chasuble, begins the service by censing around the table of the holy oil and the room in which the dying person lies. He comes to stand before the table, his face to the east.

10 Through psalm, canticle, scripture reading and a kind of expository prayer the service moves from a direct confrontation with the experience of suffering to one in which the typology of the oil is developed. Hymns (tropari) punctuate each of the readings, bringing home the theme and specifying the "image" of the oil as discussed in the readings of the scripture.

11 Recognition of the trauma, the horror of death, is the point from which the service begins, the initiation of consciousness into the experience at hand. The question as to why death exists in the very midst of life is addressed in the chanting of Psalm 51.

12 Here we have the significance of all suffering. All that is destructive of life is brought into the world by sin. It is not the wish or act of God, the creator of life, for this to be. Yet life is filled with death. This cannot be denied. The ritual moves from the encounter with the suffering of the devotee and identifying its origin in the fall of man from grace, to the "image" of the oil. The image of hyssop, the healing substance (interpreted here as the holy oil), about to be applied to the sufferer is invoked for the first of many times.

13 The breadth of the images is worth brief consideration. They will return again and again throughout the set of rituals we are considering. It is, in fact, these images that marry the experience of the individual with the meaning of the cosmos.

14 In a troparion (hymn) God is invoked as he who "makest glad the soul and preservest also thy faithful by oil." He is asked to "show compassion also unto those who draw near unto thee through the Oil" (p. 335). The oil is a pledge of salvation. A reference to the "olive-branch unto the abating of the Flood," evokes the escape of Noah and his kin from universal destruction. Oil as the fuel, the "lamp of the light divine," is invoked. The salvific action of Christ is brought into the typology as the "chrism incorruptible [which doth] empty itself utterly in grace and purify the world" (p. 336). The anointing of warriors is noted in a "Hymn to the Birth-giver of God" (p. 336), as is the anointing of kings "by the hands of the High Priests." The Birth-giver of God, Mary, is seen as "a fruitful olive-tree, in the abode of thy God, O Mother of the Creator, and thereby the world is seen to be filled with mercy." "Thy seal is a sword against demons."

15 An additional list of images is given: that of saints who in their struggle for union with God have shown a way through the awfulness of death. Each is invoked with specific reference to his or her genius in this regard: the Great Martyr Demetrius (died at Thessalonica, A.D. 306) whose bones still exude chrism and are famous for their healing powers; and Nestor, a young Christian who conquered the Emperor's favourite gladiator, an accomplishment for which he was duly martyred; St. Panteleimon of Nicomedia, an early Christian physician and miracle worker (martyred A.D. 296); the "Unmercenaries," so titled as disinterested benefactors who alleviate the pangs of soul and body, most of whom were physicians of the early Church. St. Nicholas the miracle worker, perhaps the most popular of saints, is invoked as well.

16 Images of biblical and sacred tradition are all brought to bear on the situation facing the suffering servant. In a concrete sense the sufferer is placed at the centre of scripture and tradition. He and his experience are "offered up," like Christ and the saints. The experience of suffering is informed by, and through identification with, these grand images of meaning. They are "saint and martyr." All the images offered in the rituals are images with which the devotee can possibly identify. All can be drawn on as sources of meaning in the midst of the utterly meaningless circumstance of one's suffering and possible death. All can be identified with as a kind of sanctification of one's pain and sorrow. And this is true for all those who are present, the dying and those who mourn.

17 The entrance of suffering into the world is a consequence of sin, and the identification of the sufferer with Christ and the saints of the tradition suggests not that he or she is "personally" suffering for sins committed, though the personal sins too must be offered up, but that like Christ and the saints who died because of sin and for its redemption, the sufferer too is a victim, its crucible of redemption. How is this initiation into Christ and his triumphant Kingdom accomplished in the ritual action?

The Oil of Gladness

18 With this the priest blesses the oil, pouring it and wine into the shrine lamp on the table by the devotee. The deacon and priest read the Epistles and gospel, which are drawn from biblical texts that develop the typology of oil: James 5.10-17, Luke 10.25-28. James instructs the early Christian elders to anoint the sick with "oil in the name of the Lord: and the prayer of faith shall save the sick and the Lord shall raise him up; and if he has committed sins, they shall be forgiven him." The gospel reading gives an instruction, not to the sick but to those gathered to anoint. Typically of this ritual tradition, its focus is cosmic, touching on all aspects of reality presented by the existential situation. The gospel is the parable of the good Samaritan. It is the response of Jesus of Nazareth to a lawyer who questions him about what to do to inherit eternal life. Unsatisfied with the answer Jesus gives (the classical Jewish answer), "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind; and thy neighbour as thyself," he queries, "who is my neighbour?" To this Jesus replies with the parable, which paints a rather rude picture of the priest and Lévites, leaving the salvific action to the "untouchable" Samaritan who "had compassion on him, and went to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine, and set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him" (p. 343).

19 The priests are gathered around to anoint a sick and suffering devotee. The gospel reading indicts priests and points out that "one's neighbour" is in fact anyone who responds to the tragic circumstances of life. The priest presiding does so as "neighbour"; indeed, it is as neighbour that the priestly function, the sacramental life of healing is lived. To the extent that their action is neighbourly, the priests fulfill the gospel.

20 In a prayer that follows the gospel reading the priest invokes the sanctification of the holy oil.

21 The priest then takes one of the wands, and dipping it into the holy oil, anoints the sick person, in cross-form (in exactly the form used in baptism) on the brow, the nostrils, the cheeks, the lips, the breast, and both sides of the hands. This action is accompanied with a prayer that summons all those servants of God, apostles, saints and martyrs, who have been invoked throughout the service; now, they are all, in one crisp prayer, brought to bear on the situation. This prayer calls on a range of figures from the Bible and the tradition, each of which has embodied the sacred in the midst of their own dying. It ends by proclaiming the Creator as the "fountain of healing" in the midst of life, in the midst of dying (p. 345).

22 A further gospel is read, that of Jesus' call and visit to the house of Zaccheus, the publican, which typifies the openness to the healing presence of Christ. The prayer calls to the named servant (the sufferer) to open himself to Christ through confession and invokes God, "who lovest mankind," to impart his good gifts to the penitent (pp. 347-48).

23 The office of Holy Unction is structured to be sung by seven priests. Seven gospels fill out the service, with each priest reading one and anointing the supplicant with holy oil. The gospels, punctuated by long expository prayers, give a typology of sin and of the forgiveness and healing that come through the Spirit of God, symbolized by the anointing with oil.

24 Prior to the benediction, the final distinct ritual gesture occurs. If the sick person is able to rise from the bed he joins the circle of priests. If not, the priests gather around. They take the gospel book, open it, and with the text side down, place it on the head of the sick person. This little ritual action of placing the gospel on the head of the devotee is also done at the initiation to the ministries of the church. In the rubric for this action, explicit instructions are given that the priest not lay his hands on the sick. The priests pray:

The prayer beseeches the Creator for mercy and compassion, invoking the typology of such blessings and linking this circumstance to the biblical narratives of Narhan, the penitent David, and Manasse, all of whom suffered greatly.

25 The gospel book is then taken from the head of the sick person where the priests held it and given to the sick person to kiss and adore. The gospel, where the life, suffering and death of Christ, the God-man, is proclaimed, and through which the devotee learned that all of God's creation is holy and through His grace can be transfigured, is adored. It speaks of the redemption of death itself, the snatching from the darkness of that horror death, and the restoration of the mystery of mortality to the mystery of the Creator.

26 The Office of Holy Unction has been discussed in some detail. This office illustrates the marvelous way the ritual of St. John Chrysostom weaves sacred word, gesture and object around the experience of suffering and draws the devotee into the Body of Christ, thus sanctifying creation and redeeming the horror of dying. The ritual pattern, fat from merely providing an abstract set of ideas about the meaning of life and death, provides the dying and those who stand in the presence of death with language and gesture — indeed, with the necessary world through which to experience the movement of what is occurring. By "trampling down death by death," the Christ has freed the devotee to enter into the mortality that characterizes creation in all its sacredness.

27 The Ritual of the Parting of the Soul from the Body, the Burial and the cycle of memorials through which the devotee is initiated into the cosmos will be briefly dealt with next. The connection each has with the cycle of pascha liturgies, deepening the identification of the deceased with the cosmic Christ. In all cases the rhythm of the ritual, like that of Unction, is woven of word, gesture and sacred object, binding the dead with the living Christ of all creation.

The Agony of Calvary

28 In the various rites and liturgies7 that make up Holy Week we see how the Eastern Christian imagination and tradition have seen fit to contemplate the mystery of death as it was experienced by Christ. Here the myth is given ritual form, a pattern that carries over and structures the rituals surrounding the death and burial of the devotee.

29 Holy Friday begins on Thursday evening (liturgical time, taking its cue from the creation story in Genesis, begins with the creation out of darkness) with the service of "the twelve gospels." The name is taken from the juxtaposition of gospel texts ordered into twelve parts and read throughout this moving and mournful service. An account of the passion is formed out of every detail given in scripture. It takes up the agony of the arrest of Jesus in the Garden of Olives, the proceedings against him, the scourging, the crowning with thorns, his bearing of the cross, the crucifixion, death and burial. Each "gospel" is punctuated with the response, "Glory to Thy longsuffering, O Lord, glory to Thee" (p. 154). Following the fifth "gospel" a remarkable antiphon is sung. While it is sung, a cross, often life size, is assembled in the middle of the church in place of the lesser altar, the usual site of devotion for the Orthodox devotee upon entering church. The people come and adore (contemplate) and kiss the truss with its corpse.

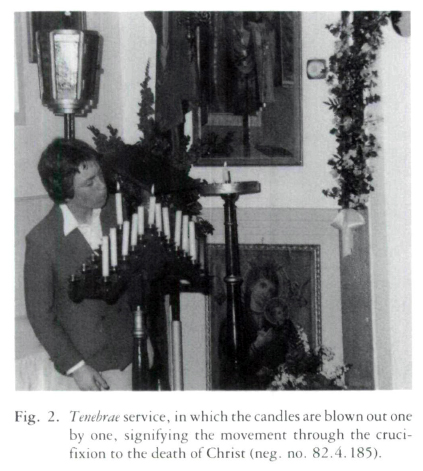

30 In some Eastern Christian churches, Romanian Orthodox for example, the tembrae (fig. 2) model is used: the twelve candles that glow at the start of the liturgy are extinguished, one by one, after each of the gospel readings.

Display large image of Figure 2

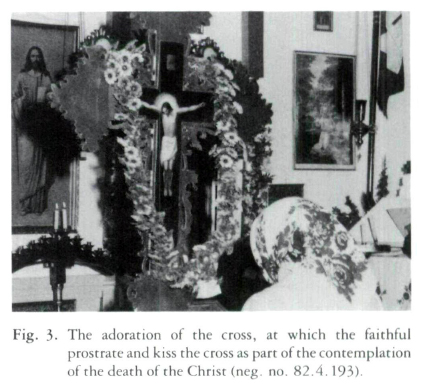

Display large image of Figure 231 The lengthy readings that structure this service contemplate the way consciousness of his impending doom dawns on the Saviour. The texts narrate the behaviour and response of those close at hand, and slowly, with unfailing step, record the journey in coming to grips with dying: the struggle to carry the cross, the agony of the cross — all the pathetic elements. The crucifix (fig. 3) with its life-size corpus moves to centre stage in the imagination and hearts of the devotee. All are invited to adore it, to claim it. For the devotees the death of Christ, in all its agony, is to be absorbed and identified with. All humankind will most assuredly find themselves at the same gate. Death, the death of God himself, is engaged as one's own.

32 Throughout the canonical hours of Holy Friday there are readings and prayers about various aspects of suffering and death. They describe the circumstances of death; they call out about the experience of dying. Each liturgical hour has readings from three psalms (except Terce, which has two), a reading from the Old Testament, and an epistle and a gospel. The whole typology of dying and death is built, as noted in the previous section on Unction, in this tapestry fashion, invoking the world of biblical images and ideas related to the expedience.

33 As in the study of all rituals, it is important to note what has been left out of the general pattern. Indeed, Holy Friday is a unique day for Eastern Christians in that it is the only day of the liturgical year when no eucharistic liturgy is celebrated.

34 During the afternoon of this day of sorrows a "burial service," the Vesper of Holy Friday, is celebrated. Three Old Testament readings develop the typology of the death. In the first one (Exodus 33. 11-23) God is saying to Moses: "While my glory passeth by...I will put thee in a cleft of the rock, and will cover thee with my hand while I pass by." This is a curious passage, which the Church has taken as a comment on the entombment of Christ. God's glory remains, and in some sense is, incarnate in his servant's descent into the darkness. There is a reading from Job as well. It is a portion of scripture, perhaps the most poignant of all biblical literature, in which the agony of human suffering at the hands of the inexplicable is described. The passion according to Isaiah, referred to also as the "suffering servant psalm," is the final reading: "despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief....Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows... But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities...and with his stripes we are healed....he is brought as a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is dumb so he openeth not his mouth....he bears the sins of many, and made intercession tor the transgressors."

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 335 In the epistle reading that follows Paul claims that the only thing he is determined to know is "Christ crucified" (Cor. 1.18-22), suggesting a kind of reorientation of the very centre of how we know the world and the meaning of creation. It is the death of god in Christ that illuminates the meaning of the creation. The gospel picks up on this theme with a composite reading, which narrates the path to the cross and the "actions" of divine love even unto death pointing to the meaning of the creation and how it is redeemed.

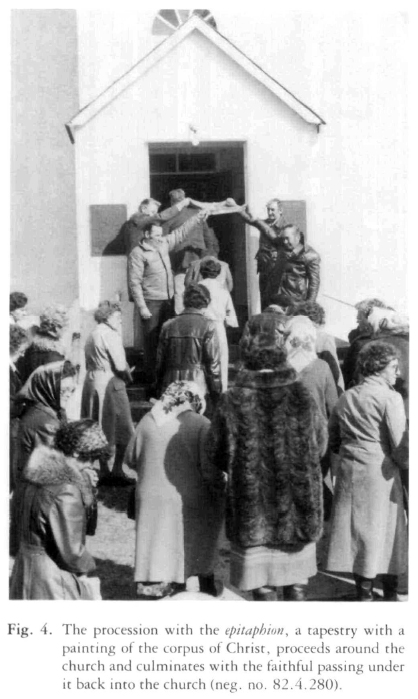

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 436 The rite of the burial takes place next. The devoted form a procession and are led around the church by the priest and the bearers of an epitaphion, a rectangular cloth with the image of the dead Christ painted or embroidered on it. The procession is flanked by the banners of the church bearing the image of the saints. The procession moves out of the church and around it counterclockwise three times. In a number of communities the epitaphion (fig. 4) is held high at the door of the church and the faithful re-enter the church by passing under it. The church has become the tomb, the place of the burial of the Christ and the place of the descent. The people are to pass, with Christ, into the darkness, into the agony of God's death. While the circumambulation takes place outside the church, the cross with its corpus is replaced with a sarcophagus. The sarcophagus sits in the same place as the coffin of the deceased at the funeral service. The priest is the last to enter the church, and with the assistance of the bearers of the icon of the dead Saviour, he moves into place beside the sarcophagus and places the "corpse" in its resting place. Incense abounds as the "body" is prepared for the journey, in the ritual of the initiation of the Godman into the eternal.

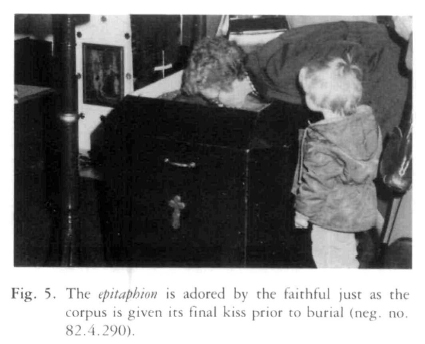

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 537 The Song of Simeon, used in many liturgies of the Church as a bridge from worship into the mundane world, is the final benediction: "Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in Peace." A fascinating shift in the use of this text can be noted. The Song of Simeon is intoned around the sarcophagus, a litany to the release of the dead God. A troparion, "The noble Joseph takes Thy immaculate Body down from the Cross, he wraps it in white linen with spices....and places it in a new tomb,"9 completes the hymns and the development of the imagery and ethos of the service. Along with the adoration and kissing of the image of the dead Christ (fig. 5), the priest anoints (fig. 6) the "corpse" just as one would see him do at a funeral and burial service. The mythic pattern is complete. "On this day, the Lord of creation stood before Pilate, and the creator of the universe is handed over to be crucified."10 So it is with the devotee. The time of dying, of death, of being handed over destroys not only the body, but in a profound way, the world and cosmos that one's life shaped and shared in. The ritual pattern is complete. The King of All Creation is entombed.

38 Within the mythic pattern of Eastern Christian culture, the sanctification of time is accomplished in the feasts of the Church, of which pascha is the pinnacle. The experience of dying, death, and burial is "formed" by the journey of the God-man, Christ. The model for the devotees is not Peter, the apostle who followed afar off, but Christ's mother, the beloved Apostle John, and the holy women, who in the gospel narrative went step by step, down the Via Dolorosa (the Way of Sorrows), up Golgotha (the Hill of the Skull) and stood, as the iconography depicts, at the foot of the cross completely present to the death of the beloved one.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 639 The pattern, form and material, both gesture and object, of pascha is brought to bear in the rituals for the dying, death and burial of the devotee.

The Passion of the Devotee: The Office of the Parting of the Soul from the Body

40 The Office of the Parting of the Soul from the Body begins with the inquiry as to the spiritual state of the dying person. Is there any word or deed, any baseness or wrath that still bears upon the mind or heart of the dying, anything unconfessed or — and note this — unforgiven? The priest's invocation begins, "Blessed is our God always, now and ever, and unto ages of ages." Psalm 51 (quoted in part at the beginning of this paper) is prayed, and a series of canticles are sung to God the Creator and to the Birth-giver of God, Mary. The pattern woven by the canticles focuses with singular clarity on the experience of dying, its alienation and horror.

41 The struggle for life, the struggle not to be humiliated in death, not to be vanquished at the end of life, is formed by the canticles. The Mother of God is invoked amidst the reality of this eternal moment. "As the mother loving mankind of the God who loveth mankind, look thou with calm and merciful eye when my soul from its body shall part; and I will glorify thee forever, O holy Birth-giver of God" (p. 364). The holy Birth-giver of God is central to this petitionary ritual. The movement across the boundary of life into the mystery of death, the initiation into the eternal, falls into the hands of her who gives birth to God Curiously, she was the one to clothe God in flesh, in the person of the Christ; and at the time of dying, it is she, the mother of incarnation, who is called upon to ease the movement of the soul from the body. She, the Birth-giver of God, is asked to watch over and assist at the journey to the eternal. So it ends: no resolution, no panacea. A simple extended contemplation of the agony of the final giving over all graphically depicted and offered up to the Creator. Mary, the channel of the incarnation of God, is asked to assist in the reverse process: the giving up of the forms of the world and the claiming of mortality. She is the guardian of this strange and horrid journey, this initiation into the mystery of death.

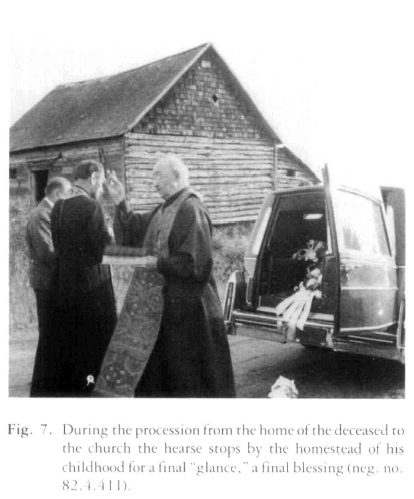

Initiation into the Cosmic Christ

42 It is still quite common in rural communities in Western Canada for the deceased to be laid out at home. A vigil is kept throughout the night, and on the morning of the funeral the coffin is brought outside to the waiting hearse. The procession moves in a direct way to the final resting place for the body. This path, however, is determined by the life of the deceased. Mourners linger outside the home, move slowly throughout the neighbourhood stopping at places in the vicinity meaningful in the deceased's life, such as the fields in which he worked or the ancestral home (fig. 7) where childhood was spent. One senses a kind of in-gathering of experience, a collecting of the particulars of this person's life. The door of the hearse is opened, the lid of the coffin is lifted, bread and a candle are placed on the road at the foot of the deceased, and prayers of blessing are said. A final glance at the playground of life is offered to all.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 743 When the procession arrives at the church, the body is taken through the gathering and placed as a kind of "lesser altar" in front of the iconostasis, forming an axis with the Great Altar. The Order for the Burial of the Dead gives structure to the ritual initiation. It notes that when an Orthodox believer has died the priest comes into the place in which the "remains of the dead man lie, and hath put on his priestly stole (epitrakhil), and hath placed incense in the censer, censeth the body ot the dead, and those present; and beginneth as usual: Blessed is our God always, now and ever, and unto ages of ages" (p. 368 emphasis added). The temporal is within the eternal. The reference throughout this ritual calls upon God the "Holy Immortal One" in counterpoint to the mortality that lies before the devotees.

44 The ritual begins by invoking God to bring the deceased to eternal rest. It is apparent from examining such rituals that this invocation is for the bereaved as well. All wish the memory of the deceased to bring peace and resolution to their lives. The great Psalms of God's majesty and of his faithful servants are chanted in responsory style (Psalms 91, 119).

45 The voice of the deceased then enters the ritual. The devotees gathered for the funeral form a chorus giving the refrain. It is a long series of reflections on human experience, on its folly and on its redemption in faith:

46 The central issue in the anthropology of Eastern Christian culture is focused on in this final call of the voice of the deceased: man as the image of God. In death the final petition is that He "who of old didst call me into being from nothingness...restore thou me to that image, and to my pristine beauty" (p.379).

47 The Church takes up the cause of the deceased, not in any juridical sense, but rather as a type and model of the human condition itself, requesting forgiveness for all shortcomings and asking that rest be given to the soul of the departed. This, of course, is a plea as much for those who live as for the dead. In the ritual surrounding death the community prays for the redemption of the memory of the deceased and freedom from any taint of the tragic circumstances of life. They pray that it be healed even now as they contemplate the mortality of life in him who has died. Along with this plea the ritual goes on building the full spectrum of human feelings and thoughts that flood into the midst of death. In canticle after canticle the existential reality is offered up:

48 This anthem by John, the Monk of Damascus, continues to immerse consciousness in the spectrum of human agony. Again we find the voice of the deceased speaking as for all mankind:

49 The Beatitudes, part of the Divine Liturgy, follow. They note that the path to the Beauty of Holiness is through a kind of giving-up.

50 The epistle and gospel readings speak directly about death (1 Thess. 4.13-18, John 5.24-30). Both claim the dead for Christ, identifying them with the Christ who took death into himself, redeeming all the righteous to the "resurrection of life."

51 With the final invocation of God's mercy, the priest moves close to the deceased lying in the coffin. In most churches the body is laid out where the sarcophagus is on Holy Friday and Saturday. It is open throughout the ritual, a stark reminder of the human image created in the image of God, of corruption in death, and of the redemption of the creation in Christ's body.

52 Standing near the head of the deceased with a cross in hand the priest prays, "O God of spirits," the prayer given at the beginning of this paper. This prayer runs through all the rituals under consideration as a kind of quiet priestly counterpoint to the "public" actions of the ritual. He concludes the prayer with the proclamation, "for thou art the resurrection and the Life." He then leans forward and gives the "last kiss" to the deceased.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 853 The Birth-giver of God and the prayers of Christ, the forerunners, apostles, hierarchs, holy ones, and saints are called upon to grant rest to the deceased and to those who stand in the vigil.

54 A final benediction marking Christ's resurrection and redemption of all creation, even in its mortal state, is given, reminding us of Gods love for all mankind.

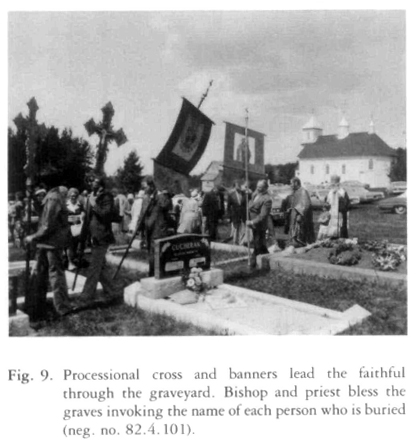

55 A Prayer of Absolution printed on a separate sheet of paper is said and every type of sin and shortcoming is forgiven. The page is laid on the hands of the deceased in preparation for the burial. All join in singing, "The earth is the Lord's and the fullness there of: The round world, and they that dwell therein." The priest anoints the body with oil from the shrine lamp; he takes ashes from the censer and spreads them on the corpse. The coffin is closed and with processional cross and banners the deceased is "led" to the cemetery and lowered into the grave. The faithful assist in placing earth on the coffin as the final hymn is sung:

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9Memory Eternal

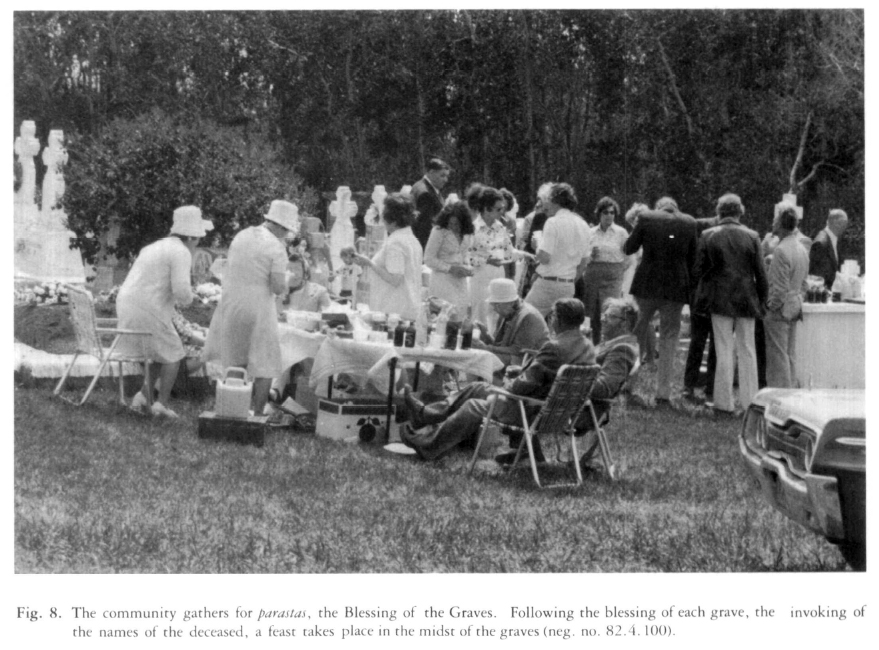

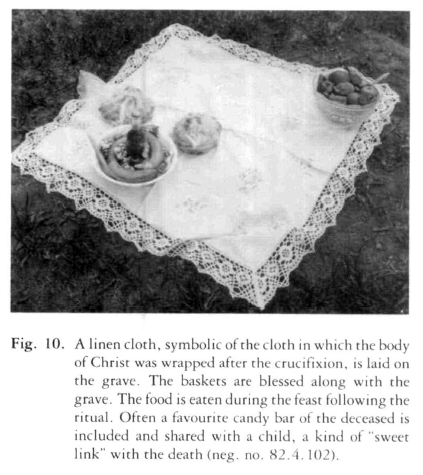

56 A cycle of memorials titled "The Requiem Office for the Dead," or Panikhidi, is prayed on a sequence of memorial days dating from the death of the beloved. This ritual is also used for the blessing of the graveyard, an annual "feast" (fig. 8) in the liturgical calendar which falls between pascha and the feast of Ascension. In many of the Slavic and Romanian communities in Canada this "village feast" constitutes an in-gathering of friends and relatives to the graveyard (fig. 9); after the service at the altar in the cemetery, each grave is blessed and the name of the deceased is read into the blessing. A linen cloth covers a portion of the grave. A basket of fruit, usually with grapes, bread, a candle and perhaps a favourite sweet of the deceased, is placed on the grave for the blessing (fig. 10). All identify the deceased with the body of Christ and with his gospel. The service follows a form very similar to those noted above: petitions for God's grace, the contemplation of human mortality, adoration of the Creator and the cosmic nature of the Christ.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10Conclusion

57 Far from the parlour ritual characteristic of burial from funeral homes,11 the Orthodox ritual for the suffering, the dying and the dead, and in memory of the deceased, contemplates death, first by anointing the body in its suffering, then at its death and just prior to burial. The human form, corruptible as it is, is adored, just as the epitaphion is adored at pascha. Loved in life, the "broken vessel" is loved in death. The raw material of life, bread and wine, which in Holy Week comes to be understood as the Body and Blood of Christ, who "trampled down death by death," is identified with the beloved dead. Their body and blood, their suffering and death, are as those of Christ. To the degree that they share in Christ, they are redeemed. They are victorious over the bondage of sin and guilt, and their memory participates in the Eternal.

58 Here we find no screening of the bereaved from the community, no "dressing" of the body as if death was anything but a horror. The circle of identification is complete: the bereaved with the deceased, the deceased with the Christ of pascha, all with the God of all creation who set the world in the firmament. The earth from which mortal flesh is made and to which it returns is sanctified in the Body of Christ. Deification, the perfection and return of the human form to the Creator, is complete. Suffering and mortality are sanctified, are part of the mythic structure of meaning made concrete in the cosmic Christ. The death of God at pascha and the death of the devotee are one.