Reviews / Comptes rendus

Royal Ontario Museum, "Georgian Canada: Conflict and Culture, 1745-1820"

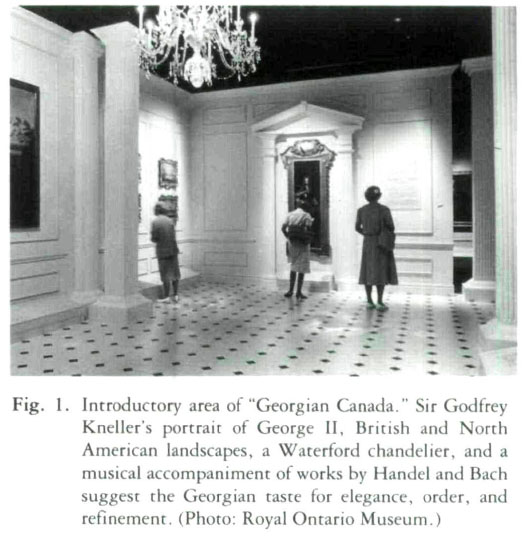

1 It was the glittering symmetry of a cut-glass chandelier that first caught my attention. A product of the famous Waterford Glass-works in Ireland, this choice piece of Georgian gentility found its way to eighteenth-century Montréal, where it undoubtedly graced the residence of one of that city's most prominent citizens. It was eventually donated to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. For a few months last year, however, the chandelier was moved once again, this time to Toronto. There, from June 7 to October 21, it graced the entrance to the Royal Ontario Museum's major bicentennial exhibition, "Georgian Canada: Conflict and Culture, 1745-1820." Beyond the chandelier's stunning elegance as an introductory statement to the ROM's feature show for 1984, the piece also served symbolically to express many of the most significant ideas associated with the "Georgian Canada" exhibition. There was, for example, the unmistakable emphasis on the good taste and refinement of the Georgian tradition. This was complemented by the exhibition's strong interest in the role of the sophisticated and socially dominant elements of colonial society. These ideas, profoundly influenced by British and American cultural values, were used to portray the life-style and sensibilities of the colonial elite during this formative chapter in the Canadian story.

2 This was a major loan exhibition combining elements of the ROM's Georgian collection with select examples of the fine and decorative arts borrowed from over fifty important collections, in Great Britain, the United States and Canada. Donald Blake Webster, the ROM's Curator of Canadiana, was responsible for assembling and interpreting the furniture, silver, weapons, glassware, ceramics, archival material and fine art that comprised the 250 pieces in the exhibition. Webster has shown a long-term professional commitment to identifying and documenting certain aspects of the Georgian tradition in the Canadian context. To a large extent, this project was realized because he was able to draw upon his considerable expertise and his scholarship in the field of Georgian decorative arts. The presentation was not only a major achievement for the ROM, indeed, in the words of Edwin A. Goodman, Chairman of its Board of Trustees, it was "the most complex exhibition the Museum has yet organized."

3 A statement near the entrance of the exhibition indicated I hat its objectives were to trace the effects of colonial conflicts in Canada's evolution and to recapture a sense of the eighteenth century's taste for elegance, order and refinement. These twin themes "conflict" and "culture" were subsequently developed in a chronological manner throughout the remainder of the exhibition. An elaborate catalogue accompanied the exhibition and provided some additional information about its objectives. ROM Director, Dr. James E. Cruise, tells us that "Georgian Canada," "is not an exhibition conceived primarily for scholars and specialists." Donald Webster, in turn, advises that the exhibition was intended to dispel certain myths which have grown up in the popular mind. One of these myths, according to Webster, is the notion that everything m Canadian history prior to Confederation is of little consequence and is perceived as a sort of "dark ages." Another myth is that Canada's development to nationhood was peaceful, orderly and uneventful. And a third, is the belief that Canada was settled mostly by farmers and frontiersmen whose attitudes and personal possessions somehow reflected simple, pioneer preoccupations. Although some may question Webster's assumptions about how the man on the street understands his history, certainly there is no question that "Georgian Canada" was intended tor a broad, general audience. The interpretation of Canadian history presented in the exhibition was offered as a corrective to what the exhibition's organizers felt is a widely held popular fixation with the backwoods and the barnyard — what Webster has referred to in his 1979 book, English-Canadian Furniture of the Georgian Period (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson), as the "pioneer syndrome." Thus in order to clarity these popularly held "misconceptions,'' the exhibition linked the ideas of "conflict" and "culture," and expressed them through a carefully selected collection of fine and decorative art objects. This particular arrangement of objects and ideas was brought together to represent the formative influences of the colonial experience.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 Donald Webster observes in the introduction to the catalogue that the project was undertaken with the idea "that no museum exhibition had ever yet tried .to cover in one sweep the whole age of modern Canada's creation." Although this statement overlooks the National Museum of Man's permanent exhibition, "A Few Acres of Snow," which attempts to do just that, nevertheless, it is valid to consider "Georgian Canada" as a very important event for those of us interested in the dynamic linkages between idea and object, particularly as manifested in the increasingly close working relationship between history and museology. Without question, this exhibition was one of the most ambitious temporary shows to be presented in Canada in some time. As well, the exhibition catalogue, which contains an effective introductory essay by Dalhousie University historian, Michael S. Cross, detailed catalogue entries by Donald Webster and a section devoted to biographical sketches of the fifty-six artists represented in the exhibition, by Irene Szylinger, exists as a lavish and lucid record of the event. Those who did not actually see "Georgian Canada" will want to study the catalogue for a detailed profile of the various themes and the content of the exhibition. Both exhibition and catalogue deserve extended comment and are worthy of critical analysis. In a brief review article of this nature, however, it is difficult to do justice to a project of such considerable proportions. Therefore, I will confine my discussion to certain aspects of the design and curatorial components of "Georgian Canada."

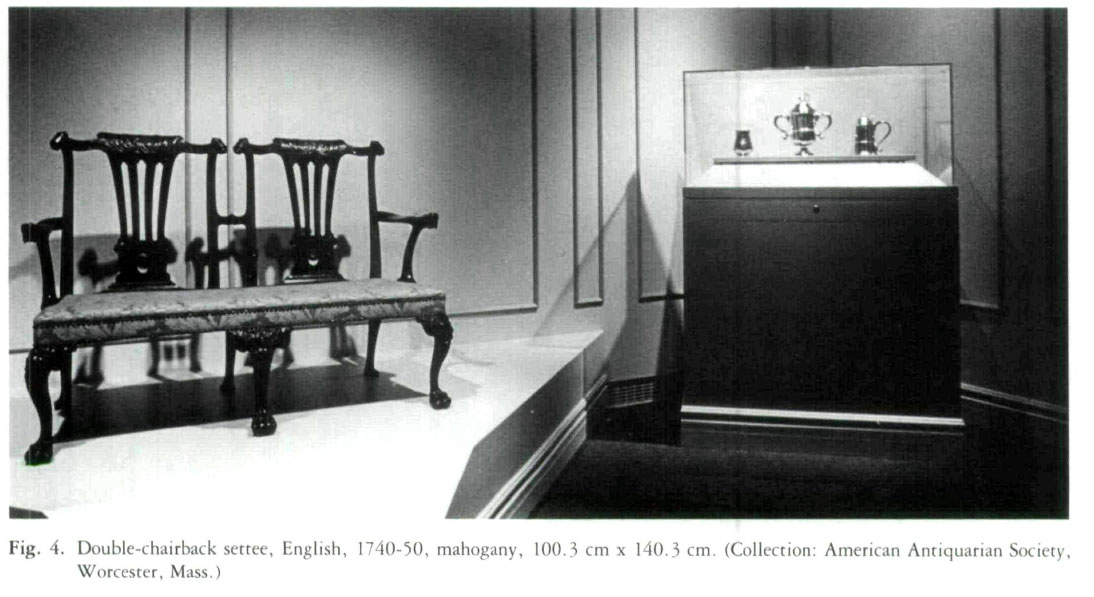

5 The exhibition was characterized throughout by powerful objects and competent design. In fact, my lasting impression of the show is based to a large extent on the overall quality of the actual presentation of objects and information. Every detail was well executed, sensitive to the exhibition's historical theme, finely appointed, and immaculate. The exhibition captions, although only in English, were attractive and precise; the use of large fluted columns in the Georgian manner; the gentle colour variations in pastel shades of pink, blue, green, yellow and brown, which appeared on walls, cases and panels, in relation to chronological progression of theme and artifact; the alternative use of floor coverings when the setting shifted from England to North America; an interesting, unpredictable and spacious traffic flow; all of these elements coalesced in the mind's eye to complement the splendor of the fine and decorative art being presented. "Georgian Canada" was a visual feast.

6 On the other hand, with such a vast undertaking, one that its curator described as, "a very broad-brush panorama of Georgian Canada and the events and people that shaped it," it is not difficult to find a few weak points. It is in this context that I want to make a couple of constructive comments on the exhibition's curatorial method.

7 While it is important to measure an exhibition in terms of its popularity with the general public, there is also the matter of the project's scholarly significance. It seems to me that a major exhibition presentation should not only reach out to touch a large audience, but to be of lasting significance, it must touch that audience in a way that translates the most recent scholarship related to the exhibition's theme(s) into a popular, three-dimension.il format. Surely, the curator's ultimate responsibility is to share the results of his/her scholarly research in appropriate academic disciplines, with the general public. This process of communication, of interpretation, is at the heart of curatorship. It occurs most effectively through the medium of the exhibition. Here is where history and museology meet. Here is where history curators have a special opportunity to adapt the theoretical insights and the applied techniques of material history in the service of the museum's most visible trademark - the exhibition. The great museum exhibitions are not only popular, they are also progressive.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 What, then, did "Georgian Canada" achieve museologically and historiographically? The ROM is an institution that operates on the basis of advanced professional standards, that prides itself on its leadership role within the profession. Inevitably, its exhibition programming will be judged against these same high museological standards, particularly in so far as the qualities of innovation and originality are concerned. Regrettably, there were elements in "Georgian Canada" that did not meet these particular expectations. In the realm of both museology and historiography this reviewer found the exhibition to be conservative and rather unimaginative.

Display large image of Figure 3

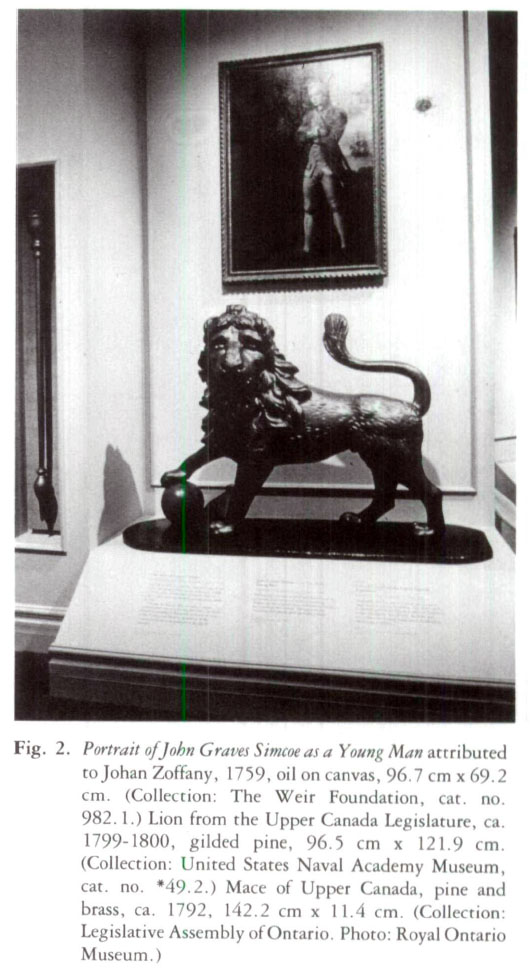

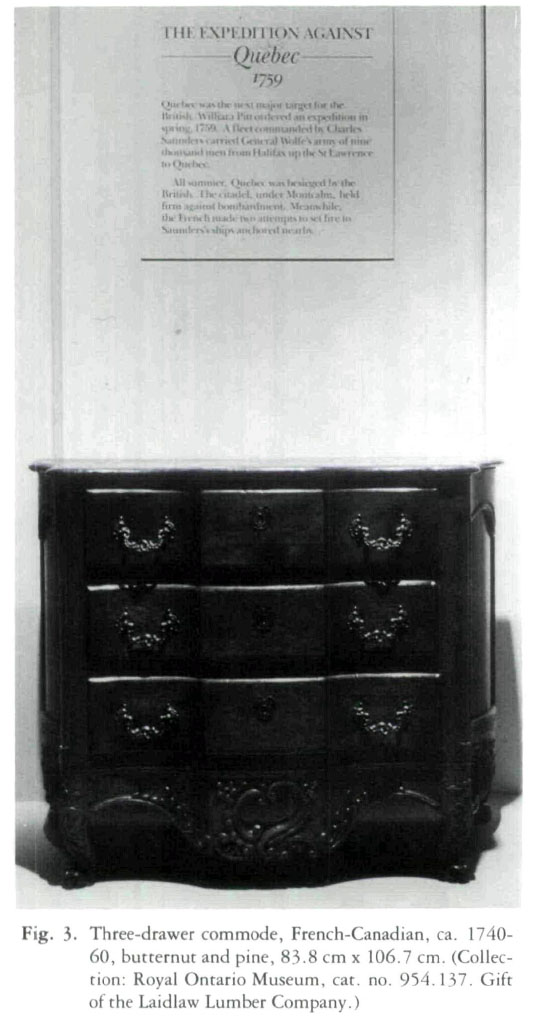

Display large image of Figure 39 The exhibition's dual focus on "conflict'' and "culture" effectively forced the adoption of a particular interpretation of Canadian history — one that is at least a generation out of date. Few will question the profound impact of war and conflict in the development of the nation. Similarly the power and influence shared by small elites is generally recognized and understood. Yet by dwelling almost exclusively on the role of elite groups, by structuring the exhibition around the elaborate accoutrements of the colonial military and the elegant possessions of a cultured gentry, we are presented with a view of the Canadian experience seriously out of step with current patterns in historical scholarship. The focus on some of the most elegant examples of fine and decorative arts of the period resulted in a version of history "from the top down." By dwelling on the experience of the privileged few, "Georgian Canada" effectively obscured key aspects of the Canadian story. What about the Georgian mind? Why was there only passing mention of the intellectual energy and creative ferment of the eighteenth century? What about the story of settlement, of family and community life, of the establishment of key commercial operations, of local entrepreneurship, of the implicit and profound links between religion and culture, of the prevailing values and expectations of the entire colonial population? The "ordinary" Canadians of the period are conspicuous by their absence.

10 It is unfortunate that a somewhat narrow art history/decorative arts paradigm was employed in relation to the interpretation of artifacts. Beautiful objects may serve well as documents; however, documents do not always have to be beautiful. A more comprehensive conceptual framework would have permitted a more satisfying level of artifact analysis incorporated into the exhibition's storyline. One would have expected to find evidence of more intensive artifact analysis in the tradition of the growing body of published material history/culture literature in both Canada and the United States. "Georgian Canada" has little to offer the practitioner of material history in terms of either the theory or the practice of artifact interpretation.

11 Beyond "Georgian Canada's" conceptual limitations, there was also the matter of information and artifact content within the storyline. One was struck, for instance, by the overwhelming concentration on the historical experience of Upper and Lower Canada. The passing references to the four Atlantic colonies, to Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, certainly projected a distorted view of the colonial reality during the period in question. A major caption on the Loyalists noted that some 30,000 went to Nova Scotia, but failed to mention that only a fraction of that number of refugees found their way to Upper Canada. Ample space was devoted, nonetheless, to the events, issues and personalities responsible for the establishment of the colony of Upper Canada, while there were virtually no references to the political origins of the four colonies on the Atlantic seaboard. This imbalance in the textual information was paralleled by an unfortunate tendency to provide inordinate space for displaying examples of Georgian material history with an Upper Canadian connection. The rich material evidence from the Atlantic colonies was given short shrift, in spite of the fact that important examples of such artifacts were readily available in the ROM's own Canadiana Collection.

12 Certainly the lasting accomplishment of the exhibition was the fact that such an outstanding collection of Georgian material history was located, assembled in Toronto and presented to Canadians. An international operation of this delicacy and complexity was a feat in itself. The list of lenders to the exhibition reads like a museological "Who's Who." This venture was not only a costly one, it also called for a broad range of curatorial "skills," not the least of which were diplomacy, determination, patience and faith. For the collector and student of the fine and decorative arts, for the descendants of the United Empire Loyalists in Ontario, and, I suspect, for the majority of the ROM's visitors, the exhibition can be considered a success. It certainly succeeded in realizing its objective as a major event in the Ontario bicentennial programme of 1984. One cannot help but wonder what the ROM has in mind for an encore during Ontario's next bicentennial celebration, in 1991.

Curatorial Statement

13 "Georgian Canada: Conflict and Culture, 1745-1820," in its logistical complexity and number and size of pieces, is probably the largest single exhibition yet developed and produced by the Royal Ontario Museum. The active development time, from November 1981, was considered tight at the outset, but organization and production was still possible. The scheduling of the Ontario bicentennial mandated an exhibition opening not later than October-November 1984, and preferably earlier.

14 The initial concept, for an exhibition of the art and artisanship of Georgian Britain, had emerged originally in 1979, but in internal discussions gradually swung in the direction of North America and Georgian Canada. Its purposes shifted as well. The exhibition was still to emphasize, visually, the arts of the British Georgian age, but material selections were to focus now on Canadian-oriented concepts and themes, and to include Canadian and American, as well as British, paintings and objects as examples of Georgian design and fashion influences on the socially dominant segments of early English Canada.

15 The primary aim in composing the exhibition was to offer elegance and opulence. The exhibition is not in any way oriented to the agricultural pioneer aspect of life, but is directed to that other, and largely ignored, area of early Canada, the mansions of Halifax, Saint John, Québec, and Montréal. The urban upper strata of English Canada from the beginning included the tastemakers and fashion and trend-setters as it did the decision-makers of early Canada. It included people with a taste for opulence and the wealth to pursue it, those who could patronize artists, fine cabinetmakers, and silversmiths, those who could travel to England or New York, and those who maintained a cultural life, from reading to music. Thus "Georgian Canada" was composed, very deliberately, as a highly elitist exhibition.

16 The second requisite theme was historical. Exactly as Canadians have been immersed in the pioneer aspect of history to the virtual exclusion of all else, so have they been conditioned to consider 1867 and Confederation as the dawn of creation, with everything that went before as a misty dark ages. With most museum-going visitors only remotely aware of eighteenth-century British North America and its origins, or of the four separate wars fought in part on Canadian territory, or of the real foundations of modern Canada, a historical chronology, with a substantial military focus, was essential. In keeping with the aim for elegance and opulence, the historical aspect had to be achieved with the finest pictures and objects that could be obtained and that fit the concepts.

17 In two years of discussions the exhibition concepts had been largely settled and required only refinement, as the project at last became operative in 1981 with the assurance of financing from the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Culture. To the ministry's and the Ontario government's great credit, though this was officially an Ontario bicentennial project, the approved exhibition plan covered a national scope, and much of its chronology predated Ontario. There were no suggestions to change the concepts into a solely Upper Canada exhibition.

18 The target opening date of June 7, 1984, was agreed in February 1982, by which time the exhibition concept and themes were largely firm, and core inclusions were already selected or under consideration. Most of 1982 was taken up in heavy reference and research, identification of specific paintings and objects for tentative inclusion, and constant travel to other museums and institutions in Britain and the United States as well as Canada. The first loan requests began that spring, followed shortly by the start of writing catalogue entries.

19 Most prospective lenders were extremely cooperative, though we were largely asking to borrow from their own galleries rather than storerooms. There were, inevitably, pieces that could not be borrowed because of precommitment to other exhibitions, or not be loaned for conservation reasons. Part of initial research, however, focused on identifying options in case of loan refusals; we expected some, so these problems were resolved fairly simply.

20 Perhaps the greatest difficulty came with the portraits of George II, George III and Queen Charlotte, and George IV. These portraits were done by the dozens if not hundreds in full figure, half figure, and head-and-shoulders formats. We particularly needed one of the full-figure coronation portraits of George III by George Ramsay, and the matching portrait of Queen Charlotte. Many, in the great houses of England, had not been moved since first hung and were not in travelling condition. Others, in public areas of palaces and government buildings, were also not available. After some searching, the exhibition's Ramsay portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte were borrowed from the Indianapolis Museum of Art, one of the only two pairs in North America.

21 George IV was even more difficult. The initial selection, the huge Copley portrait of George IV on a horse at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, was too large to get out of the MFA, too large to transport to Toronto except slung under a helicopter, and too large to move from the ROM loading dock to the special exhibitions gallery without substantial building alterations. The Copley was a "no go." We finally settled on a fine large full-figure portrait of George IV by Sir Thomas Lawrence, given by the king, preceding a royal visit, to the city of Dublin in 1821, which arrived nestled in the hold of a Boeing 747, the only commercial plane with the capacity to contain such a picture.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 422 In spite of such adventures, by September 1983 all loans were agreed and exhibition content settled with 25 1 pieces, approximately eighty per cent coming on loan and some twenty per cent from ROM collections. Gallery design was by then well advanced and catalogue writing nearly completed, with illustrations arriving from lenders.

23 Because of its cost and difficulty, "Georgian Canada" was scheduled for an unusually long showing, five and a half months from June 7 to October 21. There was never, however, any serious consideration given to circulating the exhibition to other museums. Given the diversity of lenders and the nature of the pieces, from huge canvasses to very fragile furniture and silver, having the exhibition travel as a unit was impractical if not impossible.

24 Transportation and arrival of incoming loans, including live pieces from Her Majesty the Queen, was staggered throughout March, April, and May, and was carried out with few adventures and no disasters. Installation began on May 1, and aside from some engineering issues — the assembly of a thousand-piece cut glass chandelier and the hanging of fourteen pictures each weighing over ninety kilograms — proceeded smoothly. Installation was complete by June 3, in good time for press and TV previews. There was none of the usual night-before-the-opening final rush or panic.

25 "Georgian Canada" opened on schedule on June 7, with the Premier of Ontario officiating. Two publications, a 240-page fully illustrated catalogue ($18.95) and a 16-page illustrated item checklist ($1.00), were received from the printer and available three weeks before the opening. The exhibition has received heavy media coverage and universally favourable commentary.

26 The question remaining within the museum is whether the ROM can continue itself to organize such huge, complex, and expensive projects, financially such exhibitions, even with an admission surcharge, cannot possibly recover their costs, and catalogues are priced at too small a percentage above their unit costs to be saleable at trade discounts to book shops. The ROM cannot afford to stage these exhibitions from its own operating revenues; special exhibition financing must in any event come from elsewhere.

27 At a time when the ROM is under great pressure to focus its prime energies on developing additional permanent galleries — a program that will take another eight years to complete - there has also emerged a question of the extent to which the museum is justified in tying up heavy staff resources on special exhibitions. "Georgian Canada" ultimately involved nearly a hundred people, from curators and research assistants to conservators, designers, preparators, carpenters and painters, many for lengthy periods. In an institution of relatively fixed resources, such a special exhibition effort can only detract from and in effect delay progress on the permanent galleries which are the current prime mandate. The museum is thus shortly going to have to make some hard decisions, and only time will tell whether "Georgian Canada: Conflict and Culture" was the last of the biggies.