Reviews / Comptes rendus

Canadian War Museum, "Women and War"

1 "Peace is the Dream of the Wise/War is the History of Man" reads the plaque over the entrance to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. For almost two decades now, feminists have argued that the allegedly generic "man" usually operates as a gendered term referring to the male half of the human species. A case in point is the Canadian War Museum itself, which since its founding and despite the non-discriminatory claims advanced for the use of "man," has housed permanent and travelling exhibits dedicated more or less exclusively to recalling and recording men's participation in war.

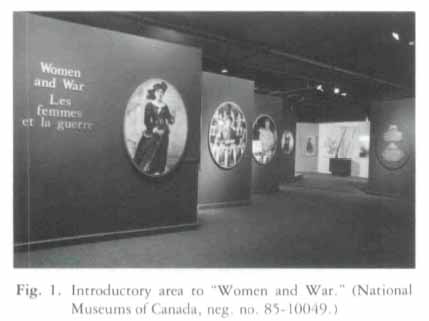

2 As a corrective to this decades-long prioritization of the male, a group of women led by free-lance researcher Nancy Miller Chenier and with the assistance of the National Museum of Man [sic] and the National Museums Corporation organized and mounted "Women and War: A Special Exhibition Highlighting the Role of Canadian Women at Home and Abroad during Periods of Conflict throughout Canada's History." The exhibit opened at the Canadian War Museum on July 26, 1984, to close September 1985 but, in recognition of its importance and drawing power, has had its run extended for another year.

3 Mounting the exhibit was an act of resistance similar to that which feminists have been mounting for centuries to the overwhelmingly male orientation of patriarchal culture - the almost irresistible pull towards man as focus of attention, men as the significant actors, the male as the norm of human activity. As far back as the French writer Christine de Pizan (1364-1430?),1 feminists have found it necessary to search among the relics and records of the past for examples of women as central figures in the drama of human life in order to challenge the marginalization of women at the hands of male chroniclers. Feminists have also found it necessary to rescue from obloquy those women whose exceptional public prominence gained them the begrudged and often captious attention of male biographers. As earlier generations of feminists were incapable of wresting control of the transmission of culture on an equal basis with men, their efforts at "putting women into history" have tended to be forgotten or erased. Consequently each new wave of feminist criticism and inquiry has had to undertake the task of historical reclamation afresh.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 The principal aim of "Women and War" has been the "compensatory"2 one of demonstrating that war has been every bit as much the history of the Canadian woman as that of the Canadian man. The exhibit's organizers are to be congratulated on gaining access to and putting on public display materials on women and war heretofore hidden away in the warehouses of the Canadian War Museum, their existence as unknown to the historical researcher as unseen by the museum goer. As the National Museums of Canada/National Museum of Man [sic] handout for the exhibit states: "War has always affected the lives of women. History shows that women in Canada have a long and active tradition of wartime participation."3 But until this exhibit opened, few visitors to the Canadian War Museum would have been made aware of this fact.

5 To achieve their compensatory objective, the exhibition's planners have organized the items on display into "five major thematic groupings": "Fighters and Protectors," "Care for the Wounded." "Materials of War," "In the Military," and "Economic Support." Admirably the exhibitors have sought to take the long view and thus to show women's involvement in Canadian hostilities since the beginning of the European incursion. In contrast to the plentitude of documents and debris available from recent history, however, little in the way of memoirs and memorabilia survives from the distant past. Also contemporary historical research has concerned itself more with women's involvement in the wars of this century than in those of any previous period. For these reasons the exhibit remains weighted towards the twentieth century.

6 While the "five main groupings" give structure to the exhibit, the categorization is not always conceptually clear. For example, subsumed under the heading "Economic Support" are many kinds of activities that would be more accurately described as providing moral(e) support. One display features letters written by women to fathers, husbands, brothers and fiancés serving in the forces far from home.

7 There are also some difficulties with the categorization of "In the Military" as separate from "Fighters and Protectors." The conceptual separation as well as the spacial location of "Fighters and Protectors" at the start of the exhibit, four sections ahead of "In the Military," suggest chronological precedence and seem to give implicit recognition to a change over time in the formal organization of militaries. As a part of the professionalization of the armed forces of western states in the course of the eighteenth into the nineteenth centuries, women were gradually excluded. Before that, in the words of Barton C. Hacker, "[w]omen were as much a part of the army as men." While wives and widows as well as prostitutes could be found among their numbers, most of these women "camp followers" shared the label of whore. They formed an indispensable part of the military, providing a whole range of essential services beyond procreational as well as recreational sex. They did the cooking, sewing, laundering, ironing, housekeeping, nursing, and provisioning of food, drink, tobacco and fuel. And they sometimes joined the battle. According to Hacker, "[i]n the often fluid and ill-defined contexts" of early modern warfare, "women must have fought, or at least helped in the fighting, as a matter of course in the peril of the moment."4 The "Women at the Battle of Niagara passing hot cannon balls to gunner, 1812" is in that tradition. The female Indian warriors also depicted in "Fighters and Protectors" occupy a parallel place in another culture.

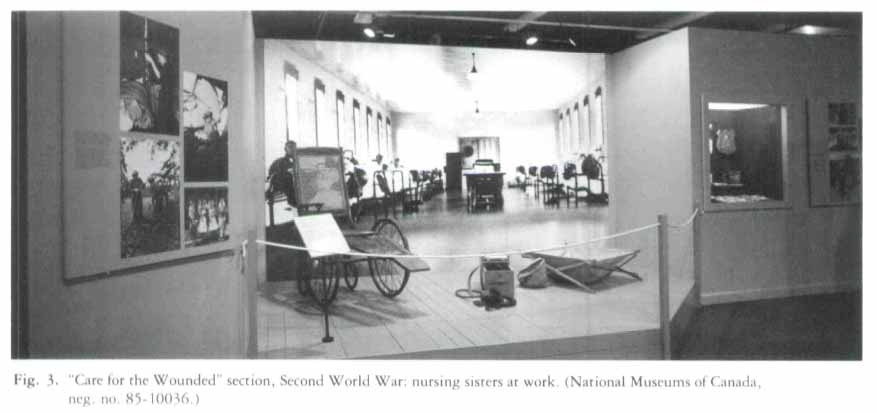

8 Thus one difficulty with the categorization lies in the fact that many of the women combatants and near combatants pictured in "Fighters and Protectors" could be said to have been "In the Military" of their day insofar as their societies or communities had militaries. Furthermore, when women were rigorously purged from the military, they were excluded not only from combat but from any and all official roles. In the early periods generally, not only women "Fighters and Protectors" but also women who provided "Care for the Wounded" and "Economic Support" would have been found "In the Military" as often as outside of it.

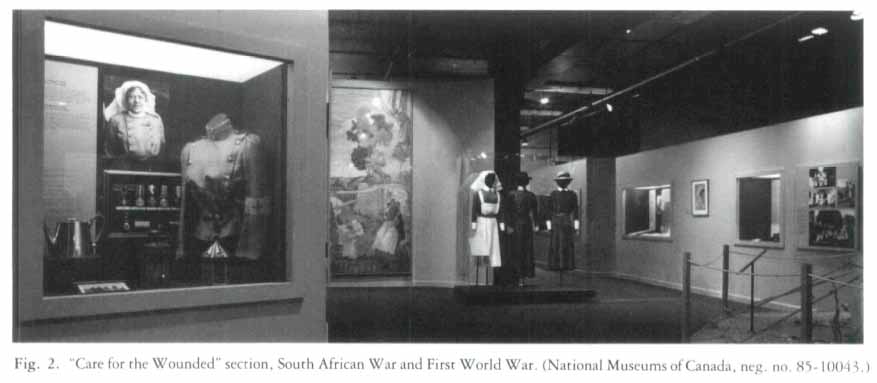

9 The exhibit's grouping "In the Military" has been reserved mainly for the women admitted (or should we say re-admitted) into the official forces of the Canadian state in the twentieth century. As these women served (and continue to serve) only in non-combatant roles, the category "Fighters and Protectors" ends up providing space for representations of women combatants and near combatants of any period, including the twentieth century, and thus loses its chronological distinction from "In the Military." The inclusion of the women's paramilitary service corps of the First and Second World Wars in "Fighters and Protectors" entails a further conceptual difficulty as it implies a desire to bear arms on the part of most members of such corps. This shifts the emphasis from the documentary evidence that their main goal, at least at the time of the Second World War, was to gain official recognition as members of Canada's armed forces content to serve in non-combatant support capacities.5

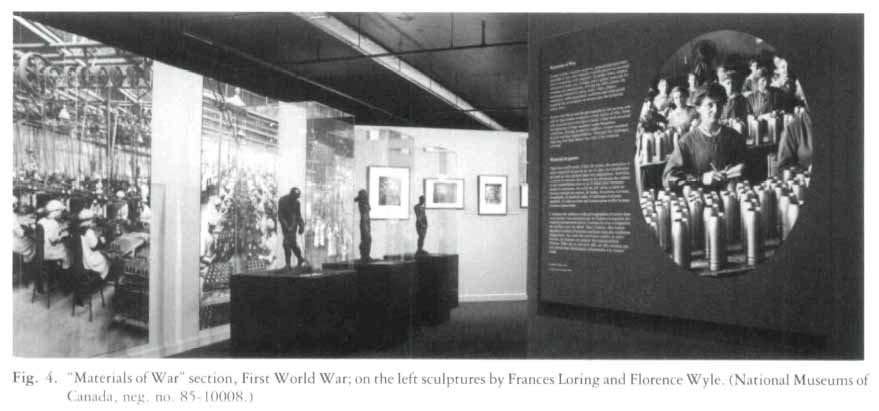

10 The grouping of "Care for the Wounded" as separate from "In the Military" is particularly misleading, since the [re]admission of the female nurses to an official role in the military antedated that accorded women serving in other capacities by about half a century. Also misleading is the caption to the pictorial representation of Jeanne Mance. "Two centuries before Florence Nightingale achieved prominence in the Crimean War of 1854-56," it reads, implying that her work was far ahead of its time, "Jeanne Mance was caring for French settlers wounded during skirmishes with the Iroquois." In fact, as Hacker reminds us, women in the seventeenth century "were widely believed to own a special talent for nursing the sick and wounded, as General Robert Venables noted when he defended the presence of soldiers' wives with the army in the West Indies campaign of 1656 by claiming 'the necessity of having that sex with an army to attend upon and help the sick and wounded, which the men are unfit for'..."6 Two centuries later Florence Nightingale faced an entirely different situation and had to fight to win an official place for trained, professionalizing female nurses from the middle class of England to care for British soldiers in foreign campaigns.

11 Categorization is, of course, always arbitrary to some extent. And within the limits of the five thematic groupings, the exhibit planners have certainly achieved some striking visual effects. They have made particularly good use of material artifacts. By selecting examples of the same type of object from two different periods, they encourage the visualization of change in mundane as well as ceremonial objects. For instance, on exhibit within the commemoration of the nursing sisters who served in the South African War of 1899-1902 is a tin Queen Victoria Chocolate Box one of these nurses received as a Christmas present in 1899- Further along one sees a tin chocolate box given for Christmas to a nursing sister serving in South Africa in 1943- Similarly, in a glass display case celebrating a nursing sister who served in two wars, a china lantern used in the South African War has been placed alongside the metal and glass lantern used a decade and a half later in the First World War.

12 An especially dramatic effect has been achieved with three powerful bronze statues by the unsung Canadian sculptors Florence Wyle and Frances Loring.7 The Munitions Worker by Florence Wyle and The Shell Finisher and The Furnace Girl by Frances Loring each stands on a plinth before a greatly enlarged photograph of women war workers from the First World War. And on the opposite wall hangs Henrietta Mabel May's rosy-hued impressionist painting Women Making Shells.

13 In another effective juxtaposition of a three-dimensional object next to its two-dimensional representation, a photograph of a group of WRCNS with a Royal Canadian Navy Emergency Ration Box is displayed in a glass case together with an actual R.C.N. Emergency Ration Box. Also shown are examples of the contents of such a box and the instructions for use on the inside of the lid. An explanatory text tells the viewer that, "[a]lthough not permitted to go to sea," members of the Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service "knew the danger faced by their fellow service men" and "were involved in the preparation of emergency rations and kits for survivors."

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

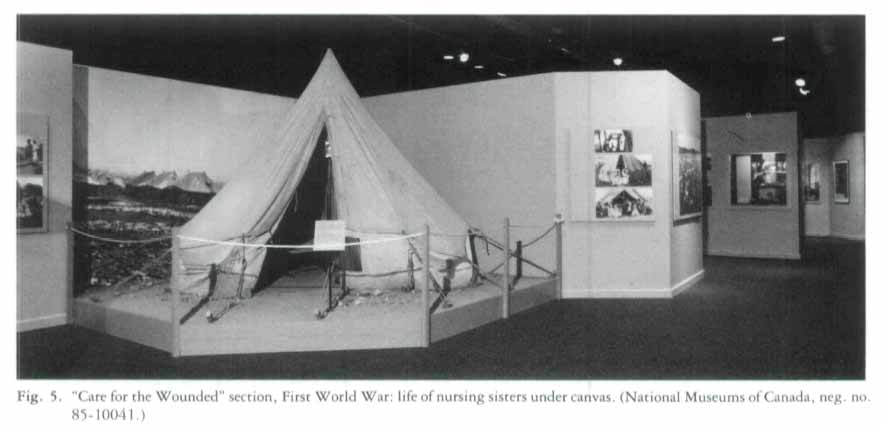

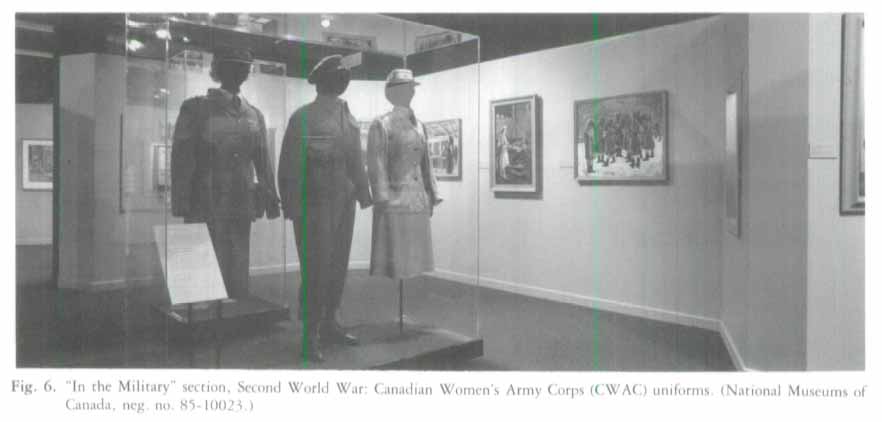

Display large image of Figure 414 Exhibited items include a continuously running videotape of Proudly She Marches, the Second World War National Film Board recruiting film for the three women's services, and a continuously playing audiotape of popular war songs, as well as uniforms, Red Cross parcels, a First World War nursing sisters' canvas tent, posters and scrap-books. Given this rich diversity, it is impossible to comment on all the arresting arrangements. Let me draw attention to only one more. At a certain point in the "In the Military" section, if one looks in one direction one sees the jacket and kilt of the uniform designed for the Canadian Women's Army Corps Pipe Band but never worn, the text tells us, because it revealed the knees of the women. Turning around to face in the opposite direction, one is looking at photographs and playbills showing female members of the armed forces wartime entertainment productions, many of whom were in chorus lines wearing very short skirts that revealed rather more of their legs than the knees. May I assume the exhibit designers intended here an ironic comment on the politics of dress codes, according to which one thing was allowed when it served the sensual titillation of the male but disallowed if it encroached on his prerogative?

15 This is one of the few instances of even implicit critical commentary in the exhibit. In keeping with their principally compensatory objective, the exhibit's planners have consciously decided to be upbeat in their interpretation. A wall poster leading into the exhibit informs viewers that the material chosen for display "highlights a few of the positive and diverse facts of women's wartime experience." Positive treatment, verging on the hagiographic, is, in fact, where the writing of women's history usually begins each time it makes a fresh start.8 As "Women and War" is the first exhibit on this subject at the Canadian War Museum and the first in Canada of such range, it is not surprising that it shows all the signs of the first phase of historical recovery. As the editors of Women, War and Revolution wrote in their Introduction, "portraits of women martyrs, soldiers, propagandists, and patriots have often marked the birth of women's history within a national speciality. They served to rectify those sins of omission in traditional accounts of wars and revolutionary efforts, and, thus, to educate scholars and lay people alike."9 But even Canadian historiography has advanced beyond that initial stage, and it is a shame that the exhibit planners were unable or unwilling to avail themselves of more critical perspectives. They might thus have avoided making such glib assessments as that women war workers "won the respect of the nation." What does that mean in the context of women's jobs sacrificed at war's end to ensure employment for male veterans and "demobilized" women war workers pressured to take on positions as domestics?

16 I found even more disturbing the lack of commentary, beyond some general words on war bringing "a great shadow over the lives of women," accompanying a photograph of four women sitting in a First World War car draped with the banner "These Four Mothers Gave to Their Country 28 Brave Sons." There is something fundamentally horrifying about women who have suffered personal loss on that scale lending their efforts to the glorification of military service. But as Diana Pedersen has already written eloquently on the failure of this exhibit to provide a "questioning exploration of the theme of women and war," I refer readers for further discussion of this issue to her article.10

17 Also disappointing is the incomplete identification of some of the items in the exhibition. This particularly plagues the coverage of the earlier periods. When faced with the impossibility of bringing to Ottawa the original of an image desired to convey a certain impression, the organizers of the exhibit have had a line-drawing facsimile created. For example, in order to represent Jeanne Mance pictorially, they have arranged for a reproduction in black and white to be made of a stained glass window commemorating her. But the museum goer is not told where the original window is located, when it was completed, or who the artist was. Another large facsimile drawing is labeled "French woman on the ramparts of the Bastille, Paris, France." We are not told, however, what medium the original was in, when it was made, who made it, or what event it celebrated. Instead the accompanying text informs us that "[f]ollowing the tradition set by this French woman, Madame Crucourt, wife of the Governor at Louisbourg, took a position on the ramparts and opposed the British besiegers of 1758." Does that mean the French woman of the picture was on the ramparts of the Bastille sometime before the French Revolution? In which war? the viewer is left to wonder.

18 Such lacunae are unfortunately not limited to the identification of the line-drawing reproductions. To represent the women's paramilitary volunteer service corps, the organizers have chosen a photograph which also appears on the cover of my volume in the Canada's Visual History series on Canadian Women and the Second World War. That it has been blown up for the exhibit is obvious, but the viewer is not told that it has also been cropped. More mystifying is the curt identification of the painting Whiz Bang Corneras oil on paper and by Stanley Turner, with no date and no explanation of the subject's significance.

19 According to Nancy Miller Chenier, "a formative evaluation study" of War Museum visitors conducted by Jenny Cave of the National Museums Corporation, disclosed that the largest proportion were under twenty-one years of age and the average time spent viewing an exhibit was twenty minutes.11 The organizers thus counter the criticism of myself and others with the disclaimer that they were not gearing the exhibit to either the scholar or the expert. But that is to subscribe to a confused notion of the purpose of exhibitions and the habits of viewers. For one thing, as now inadequately identified, Whiz Bang Corner can be fully appreciated only by the scholar or expert who is already informed that the title refers to the name given by British Commonwealth soldiers of the First World War to a German field gun shell with a low trajectory and a "whizz bang" sound.12

20 Very few if any people read every word of explanatory text provided by museum curators and exhibit designers. And one can always go through an exhibit ignoring every label or panel of text. Indeed reading the large panels, of which there are quite a few in this exhibition, is what takes time. Labels are not there for the person passing through quickly to gain only a general impression. If that were the case, labels could be dispensed with altogether. Instead labels are there for the person who, caught by a particular image or item, wants to satisfy her/his curiosity as to title, medium, date, artist, source. The two kinds of museum goer (or rather the two modes of museum going, for I myself do both) are not mutually exclusive. Communicated in small print on small labels, full and accurate identification need in no way deter the most casual of exhibit visitors while at the same time appeasing the most curious.

21 What would seem to belie the organizers' defence of under-identification is their inconsistent practice of it. While some displays leave one asking who, what, where, many others contain a plethora of information. One example is the glass case devoted to Joan Bamford Fletcher from Regina. Her story of heroic service as a member of the British First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) posted to Southeast Asia at the end of World War II is told in considerable detail and the Japanese sword she received from "an admiring Japanese officer under her command" as well as her two richly deserved service medals are all clearly identified.

22 I suspect that the exhibit's failings stem from under-funding as much as mistaken exhibition policy. To read widely on the subject of women and war and to research thoroughly each item chosen for display would have taken a great deal of time. Nancy Miller Chenier brought off a small coup in convincing the National Museums Corporation and its affiliates that an exhibit on women and war should be organized and, on the whole, she and her designer Amber Walpole of the National Museum of Man [sic] have done an admirable job. The museum officials, however, budget conscious as ever if not also dubious of the appeal of such a woman-centred project, allocated monies for a very good but not an excellent effort.

Curatorial Statement

23 You enter through the main doors of the Canadian War Museum and walk under a stone archway inscribed with the words: "Peace is the Dream of the Wise/War is the History of Man" and continue into the first floor of the permanent exhibition. Here, the displays pertaining to the early periods of conflict in Canada bear out the words — no evidence of women in the pictorial backgrounds, in the groups of artifacts. You walk through the replica of a First World War trench and off to the right, see a small display featuring a mannequin in a nurses' uniform, a photograph of women in the Field Comfort Commission, and a text panel noting the involvement of women in the First World War. Upstairs to the next floor, which contains material related to the Second World War, you notice several uniforms worn by women in the armed forces. Is this the extent of women's involvement, you ask, or more likely, do not ask, steeped as we are in the association of wartime history with military operations conducted by men utilizing other men.

24 In the spring of 1979, a conversation with a guard at the Canadian War Museum suggested the need for an exhibition on the experience of women during times of war. The Canadian War Museum was cognizant of omissions in their permanent displays and amenable to the idea of incorporating women's contributions into their interpretive scheme. Within a few months, a research proposal was accepted and a preliminary concept report was done. After several years, in the spring of 1983, the exhibition was approved and the work recommenced.

25 Research in this area had already been done by historians both at the national and the international level. Exhibitions had recently appeared in the Imperial War Museum in England and at Le Musée Royal de l'Armée in France. An extensive body of scholarly work on the Canadian experience was emerging through the work of Pierson, Nicholson, Auger and Lamothe and others. Oral history by Broadfoot, Bruce, Gray, and Read suggested a richness in personal accounts of the war periods. Developing an exhibition that focuses on the activities of women must utilize military history, social history, material history, and oral history and intertwine this material with museology and exhibition-planning concepts to generate a product for the general museum audience.

26 Exhibition planning and development will vary slightly from one project to another, but certain general principles and processes apply to each instance. One of the first considerations is the specific mandate of the presenting institution and its principal functions. In this case, the Canadian War Museum serves the Canadian public by promoting interest in Canada's wartime history and by disseminating information on this aspect of our national experience. Exhibitions, collections, publications, and educational programmes are a key facet of their work in transmitting ideas to a large and diverse public.

27 For this exhibition, the work generally proceeded along the following lines: research of artifacts and published materials to establish preliminary thematic concept; consultation among researcher, designer and evaluator to establish exhibition objectives; measurement of public knowledge and misconceptions through an evaluation study; revision of concept statement and development of preliminary thematic groupings; preparation of preliminary design; assembly and initial selection of display material with storyline; a subsequent mock-up of a portion of the draft exhibition to test clarity and effectiveness of visual and written material on the public; final selection of display material and preparation of final text and labels; presentation of final design; fabrication of exhibition and installation of artifacts. This process involved the designer and researcher through all stages as the core project team with the evaluator, editors, conservators, collection curators, donors and technical staff providing key input at relevant stages.

28 Researching this exhibition presented the usual problems encountered in the historical study of Canadian women. While women's activities in the Second World War and to a lesser extent, the First World War, have witnessed a surge of interest from the historical community, attempts to uncover the varied and often complex relation of women to war raise many questions. On the most basic factual level, little is recorded about the motivation and composition of the various paramilitary groups during these wars; about the activities of women as spies and as peacemakers; about the nurses who served with non-Canadian forces in South Africa and Britain; about civilian women working in the war zones; about military women and their post-war experience as veterans; about industrial workers and the effect of the wartime work on their health. On a broader philosophical level, many aspects of women's wartime experience during this century need to be explored before we can fully understand the effect on their lives and on future generations.

29 For the earlier periods of wartime involvement, the difficulties are much greater. Many documents relating to women's roles are deeply buried or simply lost; sources such as museums and archives are often inadequate or at times inaccurate in their cataloguing and documenting of women's artifacts. Donors themselves sometimes have forgotten significant details related to the particular role family members played in an event or an organization. In Canada, as in many countries, the pre-twentieth-century social history of women as it relates to their military or wartime activities has been explored only minimally and usually only peripherally. The exploits of people like Madeleine de Verchères and Laura Secord have been widely popularized and occasionally distorted, while other figures or groups of women have been consigned to oblivion.

30 However, in spite of the difficulties posed by scarcity of readily available published material on women and their wartime experience, the initial library research was the most straightforward part of the process. The route from this stage to final product was sometimes direct and sometimes diversionary. Identifying and analyzing the material collected by the Canadian War Museum over several decades presented the greatest challenge. The museum collection is very rich in material related to the experience of nursing sisters from the First and Second World Wars and in addition has a wide variety of uniforms and memorabilia related to women in the army, navy, and air force in the Second World War. Artifacts relating to the many activities of civilian women were less easily identified and were scattered throughout numerous donations. The display material was pulled together by examining acquisition files and then by "archaeological digs" in museum storage rooms, by taking bits and pieces of women's wartime experience from scrapbooks, from photograph albums, from brown envelopes and from candy boxes, and by amassing these fragments together. In the end, while some details remained unresolved about uniforms and dress codes, about specific pins and badges presented to industrial workers and volunteers, and about certain items of memorabilia, a story is told about the range of women's involvement.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 531 The illustrative material — artwork, posters, and photographs — came primarily from the Canadian War Museum collection with strong support for the pre-First World War period from the Public Archives of Canada. Since the budget of the exhibition did not allow for travel, additional visual material to fill identified gaps was obtained from an eastern vacation trip of the researcher, a western conference trip of the designer, and the goodwill of Jean Bruce who shared material collected for an oral/visual history of women in the Second World War.

32 Working with existing collections provided constant reminders that women were "invisible" during times of war or at least, their activities were seldom included in visual records. The well-known picture of the Americans' surprise attack on Queenston Heights shows nothing of the civilian population who were caught sleeping in their beds. Pictures of the Northwest Rebellion show uniformed soldiers advancing only on Métis men at Batoche, while newspaper accounts tell of the women and children hiding under wagons and tending to their wounded. When studying photographic archival collections, captions often reflected limited knowledge of women's roles, identifying uniformed paramilitary groups as nurses or nursing sisters as Red Cross volunteers.

33 It is impossible to research the aspects of women's wartime activities without experiencing some emotional ups and downs: the poignant messages on the postcards sent to sweethearts and husbands, the pain of viewing a scrapbook containing photographs of a son's grave in France, the sharp contrast between the beautiful scenery surrounding the nurses' workplaces and the human devastation within, the sense of achievement when a female worker received a special recommendation, the frustration over the limited collections related to pacifist activities, the knowledge that many of the women gave those years of service without expecting or receiving public or private recognition. In an effort to obtain necessary biographical information and to understand the times through which these individuals lived, several personal interviews were conducted with women who had been part of the Second World War. Without exception, the women expressed surprise at the interest in them, were self-deprecating when assessing their specific role, and mentioned frequently that this period was perhaps the most memorable for them.

34 Evaluation played a significant role in shaping this exhibition. While the work was still in the concept stage, a visitor survey was conducted to help the exhibition team in their task. The findings indicated that the largest proportion of visitors to the Canadian War Museum were under twenty-one years of age and were almost evenly divided between males and females. The most common educational level was secondary school and about half of all the visitors had read or studied Canadian war history. Knowledge about the varied roles of women was limited; the vast majority of visitors thought that homemaking and nursing were the primary female jobs during wartime - few realized that women had performed jobs as welders, aircraft mechanics or other non-traditional skills. When attitudes were measured, the younger age group was more certain than older visitors that women could do a wide variety of jobs.

35 This "front-end" evaluation study gave some general recommendations: to orient text levels to a mid-high school age; to assume some background knowledge of wartime events; to emphasize the active and non-traditional roles; to stress the positive aspects of all roles performed by women. A second formative evaluation study was conducted using a mock-up of one section of the exhibition. It helped the team develop and refine aspects of the text and the graphics.

36 The five major thematic groupings in this exhibition are: "Fighters and Protectors," "Care for the Wounded," "Materials of War," "In the Military," and "Economic Support." These groupings were selected by reviewing existing historical writing, assessing the material in the Canadian War Museum, and using information from the evaluation process. The emphasis was to be on the active roles, traditional and non-traditional, and on the general experience of Canadian women. Also within each major thematic group is a small special focus section. The intent here was to highlight an additional, related role which was part of the wartime experience but where the Canadian War Museum collection was relatively weak. Thus, "Spies," "Federal Votes for Women," "Peacemakers," "Entertainers," and "Wives, Mothers, Sweethearts" were incorporated as subthemes relying heavily on representational visual panels to convey their significance.

37 The storyline for the exhibition was developed to meet the education and knowledge levels of the Canadian War Museum public as predetermined by the visitor survey. Using evaluation methods and knowledge from studies about textual presentation, it tries to be short, concise and logical. The goal here is to convey facts and to evoke further questions, not just through labels and written material, but also through the display of objects and materials selected and arranged to present concepts and ideas.

38 The exhibition provides a broad view of women's work during times of conflict in Canada. It presents the activities of women involved in hostilities over several centuries. The early historical periods up to the South African War are represented primarily through reproductions of visual material - pictorial, photographic, and manuscript. The periods of the South African War, the First World War, and the Second World War incorporate a great deal of original material - manuscript, three-dimensional, textile, art and photographic. The artifacts are drawn primarily from the collection of the Canadian War Museum and utilize the uniforms, medals, posters, art work, equipment, manuscripts and general memorabilia characterizing the wartime experience of Canadian women.

39 The exhibition was designed to open the barrier between academic historians and the general public; to provide a starting point for increasing public knowledge of this particular aspect of our national wartime experience. It attempts to synthesize information from a number of sources and to utilize the collection of one museum to illustrate a long tradition of women's participation during wartime. It makes no claim to comprehensiveness but aims to present ideas and facts and to raise questions about omissions in our historical knowledge and in our heritage collections.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6